SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

On Saturday a car bomb in Baghdad exploded in a crowded commercial street. Kamal Mahmoud, a school teacher, witnessed the blast. He told the New York Times, "I felt the heat of the blast on my face and the bodies of two women thrown in the middle of the street covered in blood, one of them without legs." It's not clear if the women survived. Fourteen people were killed.

On Saturday a car bomb in Baghdad exploded in a crowded commercial street. Kamal Mahmoud, a school teacher, witnessed the blast. He told the New York Times, "I felt the heat of the blast on my face and the bodies of two women thrown in the middle of the street covered in blood, one of them without legs." It's not clear if the women survived. Fourteen people were killed.

Political violence has increased this year, one of the bloodiest since the partial U.S. withdrawal in 2011. According to media reports, 6,000 people died from violence in 2013, over 1,000 in September alone. These numbers come largely from deaths recorded in the press, notoriously inaccurate for a comprehensive picture of mortality in Iraq, or any combat zone.

A new study released today and published in the Public Library of Science - Medicine journal tries to create a more accurate picture of what death in Iraq has looked like since 2003. An international team of researchers from the University of Washington, Simon Fraser University, John Hopkins University, and Mustansiriya University (Baghdad) sampled 2000 households, asking for information on deaths of family and household members.

It finds that approximately one half million Iraqis died from war related causes between 2003 and 2011. A majority, more than sixty percent of the deaths, were directly caused by violence - gunshots, explosions like Saturday's car bomb, or areal bombings. The rest are attributable to social collapse, the loss of infrastructure and health care from the invasion, occupation, and political and sectarian violence that followed.

What's significant about the study is that it is the first household statistical sampling to emerge following the US withdrawal of combat troops, and therefore attempts to provide something of a comprehensive picture of violence in Iraq during the period of U.S. occupation.

Although perhaps low, the numbers from this study are devastating. It would make Iraq one of the worst humanitarian disasters - crimes if we think about responsibility - of the 21st century, second only to Congolese war in terms of numbers of dead.

Counting Bodies

Pervious numbers of Iraqi dead vary wildly. Unlike U.S. and coalition occupation forces, for which we have exact numbers, Iraq lives and deaths are not given careful attention. Demonstrating the U.S. military's attention to civilian casualties, U.S. General Tommy Franks, in reference to Afghanistan, famously told the San Francisco Chronicle in 2002 that "we don't do body counts." Those concerned with human loss of life have to find information elsewhere, and that has meant two board and contrasting approaches - using media reports on casualties, or a statistical sampling method like the one used in this study.

Basing civilian body counts on media reports is notoriously unreliable. A number of studies have found that as violence in a country increases, the coverage of violence tends to decrease. This is because as a country becomes more violent, it becomes more dangerous for journalists to attempt to access sites of conflict. Through 2010, Iraq remained the most dangerous place on earth for journalists. This means that in some instances body counts through careful media analysis can be as much 80% below actual death tolls.

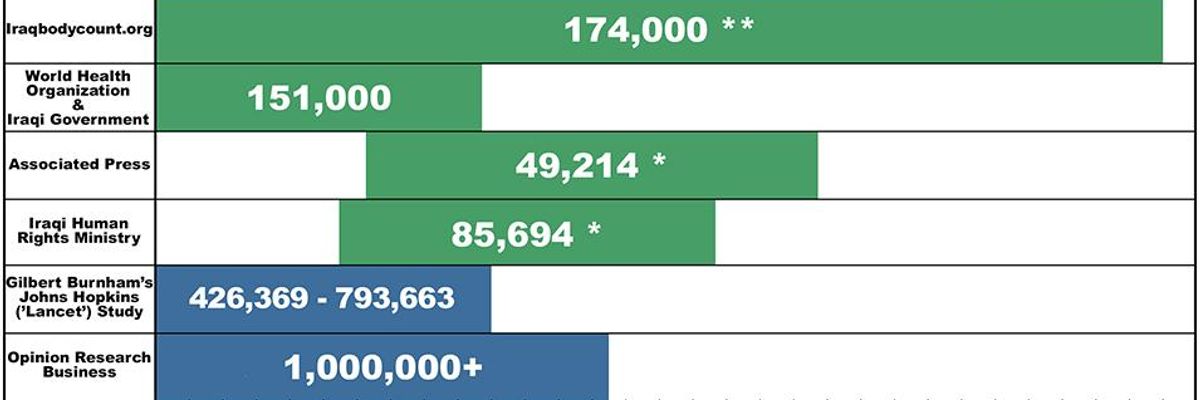

Iraq Body Count, the most visible group that uses this method, puts their figure between 114,000 and 126,000 war dead. Even though they have been hostile to previous studies using the household sampling method, they write on their website that their information is intended to be "an irrefutable baseline figure," and provide a "conservative cautious minimum" for numbers of dead.

The PLS-Medicine study uses household survey sampling methods to look at "excess deaths" from 2003 to 2011 that can be attributed to the war. Lead authors Amy Hagopian and Abraham Flaxman write that "approximately a half-million deaths in Iraq could be directly attributable to the war." But this figure is rounding up from their own numbers. Based on their survey sample, the "hard" number they offer is 405,000 excess deaths. But they seek to adjust for a large outmigration of Iraqi emigrants during the war, an estimated two million people. Based on this loss of sampling population, they adjust their figures upward by 55,000 to 460,000 war dead.

Compared to other studies, these numbers seem low. Two previous studies, one by researchers at Johns Hopkins University published in the Lancet in 2006, and another published in 2007 by a private British research firm, Opinion Research Business, put the death toll at 655,000 and over one million, respectively.

Although the authors of the PLoS-Medicine study attempted to correct for out migration, the effect of population loss and mobility may have impacted the study. The samplings produced in 2006 and 2007, at the height of the conflict, probably reflect a closer account of what really happened during the war. But these studies produced missed the remaining 4-5 years of war. The PLoS-Medicine study attempts to cover this period, and it seems unlikely that numbers of war dead, for the entire period of war, would be substantially lower than those numbers produced half way through the occupation.

The Human Impact of Numbers

Whatever the actual numbers, half a million to a million, the human cost of these numbers are hard to contemplate.

To try to understand those numbers, I think back to the stories of individuals, published periodically through the height of the war. Stories of those killed, kidnapped, tortured or displaced that jumped through the dense mist of American news coverage to remind us what war is about.

Like the story of Abeer Hamza, who stands out because of the particular brutality of her case.

In the spring of 2006 fourteen year old Abeer Hamza and her family were killed by five US service members on guard at a nearby checkpoint. The Army soldiers had been eyeing Abeer, and told her mother that the girl was "very good." In broad daylight, the soldiers broke into the Hamza house, killed Abeer parents, 34 year old mother, Fakhriyah Taha Muhusin, father Qasim Hamza Raheem, and Abeer's six year sister Hadeel. After killing Abeer's family, the soldiers gang-raped Abeer, and then killed her. They lit her body on fire which quickly spread to the rest of the house. The fire was the reason they were caught and tried for their crime.

Like Abeer, Namir Noor-Eldeen stands out for the uniqueness of his death.

Noor-Eldeen was an Iraqi correspondent for Rueters. On July 12th, 2007 a US military helicopter supporting U.S. forces in a fire fight in a North Bahgdad neighborhood mistook Namir's camera for a weapon. With glee, the copter and their support team wanted to "light 'em all up" and opened fire, killing altogether 11 people. Eight were killed in the first round of shooting, including Namir, and three more when a van arrived to help the wounded. In the copter's video feed, obtained and released by Wikileaks, the soldiers are jubilant at their accuracy, "right through the windshield," laughing as the panicked survivors "drove over a body." This in contrast to the desperation on the voices of the soldiers on the ground, including Ethan McCord, who can be heard as they discover and attempt to save a four year old girl and seven year old boy wounded in the shooting.

In contrast to Abeer and Namir, hardly anyone knows of Safa Nawar Mohammed.

Safa was riding in the back of a pickup truck in Mahmudiayah in the spring of 2006 when her truck approached a platoon of U.S. soldiers. Spooked by an earlier incident, the soldiers fired shots at the vehicle, striking Safa through the head. Although not quite dead when soldiers found her, no medical assistance was called because of the severity of her wound, and Safa died a few minutes later.

Safa is one of innumerable and largely unrecognizanced victims of the the U.S. invasion. Like those killed in the Hadytha massacre, or countless checkpoints shootings, or in the first and second battles for Falllujah.

These are the stories of the numbers of the dead found the PLoS study. These stories are multiplied by a hundred, by a thousand, by a hundred-thousand, and two hundred thousand, and we begin to approach the meaning of the study.

The Right to Heal

There have been efforts to reach out to Iraqi victims and their families on the part of U.S service members. Following the release of the Wikileaks "Collateral Murder" video, two veterans, Josh Stieber and Ethan McCord, wrote "An Open Letter of Reconciliation and Responsibility to the Iraqi People," in which they apologized for the crimes they participated in, and sought dialogue with Iraqis.

In March of this year, on the tenth anniversary of the U.S. invasion, the Organization of Women's Freedom in Iraq (OWFI), Iraq Veterans Against the War (IVAW), and the Federation of Workers Councils and Unions in Iraq (FWCUI) launched the Right to Heal Initiative. From their website:

Iraqis and veterans are coming together to hold the U.S. government accountable for the lasting effects of war and the rights of veterans and civilians to heal. The Iraq war is not over for Iraqi civilians and U.S. veterans who continue to struggle with various forms of trauma and injury; the effects of environmental poisoning due to certain U.S. munitions and burn pits of hazardous materials; and with a generation of orphans and displaced. As Iraqi civil society tries to rebuild from the Iraq war as well as a decade of U.S. bombing and sanctions, they face political repression by a corrupt U.S.-established government that is selling off the country's natural resources to foreign interests.

Along with the Center for Constitutional Rights, these groups have filed a request for a hearing with the Inter-American Commission for Human Rights.

These efforts by veteran and human rights groups need to be supported. Even with withdrawal of U.S. combat troops, Iraqis continue to live and die because of the impacts of the invasion of their country of which the car bombing last Saturday is just one incident. The PLoS-Medicine study published today helps us understand some of those impacts.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

On Saturday a car bomb in Baghdad exploded in a crowded commercial street. Kamal Mahmoud, a school teacher, witnessed the blast. He told the New York Times, "I felt the heat of the blast on my face and the bodies of two women thrown in the middle of the street covered in blood, one of them without legs." It's not clear if the women survived. Fourteen people were killed.

Political violence has increased this year, one of the bloodiest since the partial U.S. withdrawal in 2011. According to media reports, 6,000 people died from violence in 2013, over 1,000 in September alone. These numbers come largely from deaths recorded in the press, notoriously inaccurate for a comprehensive picture of mortality in Iraq, or any combat zone.

A new study released today and published in the Public Library of Science - Medicine journal tries to create a more accurate picture of what death in Iraq has looked like since 2003. An international team of researchers from the University of Washington, Simon Fraser University, John Hopkins University, and Mustansiriya University (Baghdad) sampled 2000 households, asking for information on deaths of family and household members.

It finds that approximately one half million Iraqis died from war related causes between 2003 and 2011. A majority, more than sixty percent of the deaths, were directly caused by violence - gunshots, explosions like Saturday's car bomb, or areal bombings. The rest are attributable to social collapse, the loss of infrastructure and health care from the invasion, occupation, and political and sectarian violence that followed.

What's significant about the study is that it is the first household statistical sampling to emerge following the US withdrawal of combat troops, and therefore attempts to provide something of a comprehensive picture of violence in Iraq during the period of U.S. occupation.

Although perhaps low, the numbers from this study are devastating. It would make Iraq one of the worst humanitarian disasters - crimes if we think about responsibility - of the 21st century, second only to Congolese war in terms of numbers of dead.

Counting Bodies

Pervious numbers of Iraqi dead vary wildly. Unlike U.S. and coalition occupation forces, for which we have exact numbers, Iraq lives and deaths are not given careful attention. Demonstrating the U.S. military's attention to civilian casualties, U.S. General Tommy Franks, in reference to Afghanistan, famously told the San Francisco Chronicle in 2002 that "we don't do body counts." Those concerned with human loss of life have to find information elsewhere, and that has meant two board and contrasting approaches - using media reports on casualties, or a statistical sampling method like the one used in this study.

Basing civilian body counts on media reports is notoriously unreliable. A number of studies have found that as violence in a country increases, the coverage of violence tends to decrease. This is because as a country becomes more violent, it becomes more dangerous for journalists to attempt to access sites of conflict. Through 2010, Iraq remained the most dangerous place on earth for journalists. This means that in some instances body counts through careful media analysis can be as much 80% below actual death tolls.

Iraq Body Count, the most visible group that uses this method, puts their figure between 114,000 and 126,000 war dead. Even though they have been hostile to previous studies using the household sampling method, they write on their website that their information is intended to be "an irrefutable baseline figure," and provide a "conservative cautious minimum" for numbers of dead.

The PLS-Medicine study uses household survey sampling methods to look at "excess deaths" from 2003 to 2011 that can be attributed to the war. Lead authors Amy Hagopian and Abraham Flaxman write that "approximately a half-million deaths in Iraq could be directly attributable to the war." But this figure is rounding up from their own numbers. Based on their survey sample, the "hard" number they offer is 405,000 excess deaths. But they seek to adjust for a large outmigration of Iraqi emigrants during the war, an estimated two million people. Based on this loss of sampling population, they adjust their figures upward by 55,000 to 460,000 war dead.

Compared to other studies, these numbers seem low. Two previous studies, one by researchers at Johns Hopkins University published in the Lancet in 2006, and another published in 2007 by a private British research firm, Opinion Research Business, put the death toll at 655,000 and over one million, respectively.

Although the authors of the PLoS-Medicine study attempted to correct for out migration, the effect of population loss and mobility may have impacted the study. The samplings produced in 2006 and 2007, at the height of the conflict, probably reflect a closer account of what really happened during the war. But these studies produced missed the remaining 4-5 years of war. The PLoS-Medicine study attempts to cover this period, and it seems unlikely that numbers of war dead, for the entire period of war, would be substantially lower than those numbers produced half way through the occupation.

The Human Impact of Numbers

Whatever the actual numbers, half a million to a million, the human cost of these numbers are hard to contemplate.

To try to understand those numbers, I think back to the stories of individuals, published periodically through the height of the war. Stories of those killed, kidnapped, tortured or displaced that jumped through the dense mist of American news coverage to remind us what war is about.

Like the story of Abeer Hamza, who stands out because of the particular brutality of her case.

In the spring of 2006 fourteen year old Abeer Hamza and her family were killed by five US service members on guard at a nearby checkpoint. The Army soldiers had been eyeing Abeer, and told her mother that the girl was "very good." In broad daylight, the soldiers broke into the Hamza house, killed Abeer parents, 34 year old mother, Fakhriyah Taha Muhusin, father Qasim Hamza Raheem, and Abeer's six year sister Hadeel. After killing Abeer's family, the soldiers gang-raped Abeer, and then killed her. They lit her body on fire which quickly spread to the rest of the house. The fire was the reason they were caught and tried for their crime.

Like Abeer, Namir Noor-Eldeen stands out for the uniqueness of his death.

Noor-Eldeen was an Iraqi correspondent for Rueters. On July 12th, 2007 a US military helicopter supporting U.S. forces in a fire fight in a North Bahgdad neighborhood mistook Namir's camera for a weapon. With glee, the copter and their support team wanted to "light 'em all up" and opened fire, killing altogether 11 people. Eight were killed in the first round of shooting, including Namir, and three more when a van arrived to help the wounded. In the copter's video feed, obtained and released by Wikileaks, the soldiers are jubilant at their accuracy, "right through the windshield," laughing as the panicked survivors "drove over a body." This in contrast to the desperation on the voices of the soldiers on the ground, including Ethan McCord, who can be heard as they discover and attempt to save a four year old girl and seven year old boy wounded in the shooting.

In contrast to Abeer and Namir, hardly anyone knows of Safa Nawar Mohammed.

Safa was riding in the back of a pickup truck in Mahmudiayah in the spring of 2006 when her truck approached a platoon of U.S. soldiers. Spooked by an earlier incident, the soldiers fired shots at the vehicle, striking Safa through the head. Although not quite dead when soldiers found her, no medical assistance was called because of the severity of her wound, and Safa died a few minutes later.

Safa is one of innumerable and largely unrecognizanced victims of the the U.S. invasion. Like those killed in the Hadytha massacre, or countless checkpoints shootings, or in the first and second battles for Falllujah.

These are the stories of the numbers of the dead found the PLoS study. These stories are multiplied by a hundred, by a thousand, by a hundred-thousand, and two hundred thousand, and we begin to approach the meaning of the study.

The Right to Heal

There have been efforts to reach out to Iraqi victims and their families on the part of U.S service members. Following the release of the Wikileaks "Collateral Murder" video, two veterans, Josh Stieber and Ethan McCord, wrote "An Open Letter of Reconciliation and Responsibility to the Iraqi People," in which they apologized for the crimes they participated in, and sought dialogue with Iraqis.

In March of this year, on the tenth anniversary of the U.S. invasion, the Organization of Women's Freedom in Iraq (OWFI), Iraq Veterans Against the War (IVAW), and the Federation of Workers Councils and Unions in Iraq (FWCUI) launched the Right to Heal Initiative. From their website:

Iraqis and veterans are coming together to hold the U.S. government accountable for the lasting effects of war and the rights of veterans and civilians to heal. The Iraq war is not over for Iraqi civilians and U.S. veterans who continue to struggle with various forms of trauma and injury; the effects of environmental poisoning due to certain U.S. munitions and burn pits of hazardous materials; and with a generation of orphans and displaced. As Iraqi civil society tries to rebuild from the Iraq war as well as a decade of U.S. bombing and sanctions, they face political repression by a corrupt U.S.-established government that is selling off the country's natural resources to foreign interests.

Along with the Center for Constitutional Rights, these groups have filed a request for a hearing with the Inter-American Commission for Human Rights.

These efforts by veteran and human rights groups need to be supported. Even with withdrawal of U.S. combat troops, Iraqis continue to live and die because of the impacts of the invasion of their country of which the car bombing last Saturday is just one incident. The PLoS-Medicine study published today helps us understand some of those impacts.

On Saturday a car bomb in Baghdad exploded in a crowded commercial street. Kamal Mahmoud, a school teacher, witnessed the blast. He told the New York Times, "I felt the heat of the blast on my face and the bodies of two women thrown in the middle of the street covered in blood, one of them without legs." It's not clear if the women survived. Fourteen people were killed.

Political violence has increased this year, one of the bloodiest since the partial U.S. withdrawal in 2011. According to media reports, 6,000 people died from violence in 2013, over 1,000 in September alone. These numbers come largely from deaths recorded in the press, notoriously inaccurate for a comprehensive picture of mortality in Iraq, or any combat zone.

A new study released today and published in the Public Library of Science - Medicine journal tries to create a more accurate picture of what death in Iraq has looked like since 2003. An international team of researchers from the University of Washington, Simon Fraser University, John Hopkins University, and Mustansiriya University (Baghdad) sampled 2000 households, asking for information on deaths of family and household members.

It finds that approximately one half million Iraqis died from war related causes between 2003 and 2011. A majority, more than sixty percent of the deaths, were directly caused by violence - gunshots, explosions like Saturday's car bomb, or areal bombings. The rest are attributable to social collapse, the loss of infrastructure and health care from the invasion, occupation, and political and sectarian violence that followed.

What's significant about the study is that it is the first household statistical sampling to emerge following the US withdrawal of combat troops, and therefore attempts to provide something of a comprehensive picture of violence in Iraq during the period of U.S. occupation.

Although perhaps low, the numbers from this study are devastating. It would make Iraq one of the worst humanitarian disasters - crimes if we think about responsibility - of the 21st century, second only to Congolese war in terms of numbers of dead.

Counting Bodies

Pervious numbers of Iraqi dead vary wildly. Unlike U.S. and coalition occupation forces, for which we have exact numbers, Iraq lives and deaths are not given careful attention. Demonstrating the U.S. military's attention to civilian casualties, U.S. General Tommy Franks, in reference to Afghanistan, famously told the San Francisco Chronicle in 2002 that "we don't do body counts." Those concerned with human loss of life have to find information elsewhere, and that has meant two board and contrasting approaches - using media reports on casualties, or a statistical sampling method like the one used in this study.

Basing civilian body counts on media reports is notoriously unreliable. A number of studies have found that as violence in a country increases, the coverage of violence tends to decrease. This is because as a country becomes more violent, it becomes more dangerous for journalists to attempt to access sites of conflict. Through 2010, Iraq remained the most dangerous place on earth for journalists. This means that in some instances body counts through careful media analysis can be as much 80% below actual death tolls.

Iraq Body Count, the most visible group that uses this method, puts their figure between 114,000 and 126,000 war dead. Even though they have been hostile to previous studies using the household sampling method, they write on their website that their information is intended to be "an irrefutable baseline figure," and provide a "conservative cautious minimum" for numbers of dead.

The PLS-Medicine study uses household survey sampling methods to look at "excess deaths" from 2003 to 2011 that can be attributed to the war. Lead authors Amy Hagopian and Abraham Flaxman write that "approximately a half-million deaths in Iraq could be directly attributable to the war." But this figure is rounding up from their own numbers. Based on their survey sample, the "hard" number they offer is 405,000 excess deaths. But they seek to adjust for a large outmigration of Iraqi emigrants during the war, an estimated two million people. Based on this loss of sampling population, they adjust their figures upward by 55,000 to 460,000 war dead.

Compared to other studies, these numbers seem low. Two previous studies, one by researchers at Johns Hopkins University published in the Lancet in 2006, and another published in 2007 by a private British research firm, Opinion Research Business, put the death toll at 655,000 and over one million, respectively.

Although the authors of the PLoS-Medicine study attempted to correct for out migration, the effect of population loss and mobility may have impacted the study. The samplings produced in 2006 and 2007, at the height of the conflict, probably reflect a closer account of what really happened during the war. But these studies produced missed the remaining 4-5 years of war. The PLoS-Medicine study attempts to cover this period, and it seems unlikely that numbers of war dead, for the entire period of war, would be substantially lower than those numbers produced half way through the occupation.

The Human Impact of Numbers

Whatever the actual numbers, half a million to a million, the human cost of these numbers are hard to contemplate.

To try to understand those numbers, I think back to the stories of individuals, published periodically through the height of the war. Stories of those killed, kidnapped, tortured or displaced that jumped through the dense mist of American news coverage to remind us what war is about.

Like the story of Abeer Hamza, who stands out because of the particular brutality of her case.

In the spring of 2006 fourteen year old Abeer Hamza and her family were killed by five US service members on guard at a nearby checkpoint. The Army soldiers had been eyeing Abeer, and told her mother that the girl was "very good." In broad daylight, the soldiers broke into the Hamza house, killed Abeer parents, 34 year old mother, Fakhriyah Taha Muhusin, father Qasim Hamza Raheem, and Abeer's six year sister Hadeel. After killing Abeer's family, the soldiers gang-raped Abeer, and then killed her. They lit her body on fire which quickly spread to the rest of the house. The fire was the reason they were caught and tried for their crime.

Like Abeer, Namir Noor-Eldeen stands out for the uniqueness of his death.

Noor-Eldeen was an Iraqi correspondent for Rueters. On July 12th, 2007 a US military helicopter supporting U.S. forces in a fire fight in a North Bahgdad neighborhood mistook Namir's camera for a weapon. With glee, the copter and their support team wanted to "light 'em all up" and opened fire, killing altogether 11 people. Eight were killed in the first round of shooting, including Namir, and three more when a van arrived to help the wounded. In the copter's video feed, obtained and released by Wikileaks, the soldiers are jubilant at their accuracy, "right through the windshield," laughing as the panicked survivors "drove over a body." This in contrast to the desperation on the voices of the soldiers on the ground, including Ethan McCord, who can be heard as they discover and attempt to save a four year old girl and seven year old boy wounded in the shooting.

In contrast to Abeer and Namir, hardly anyone knows of Safa Nawar Mohammed.

Safa was riding in the back of a pickup truck in Mahmudiayah in the spring of 2006 when her truck approached a platoon of U.S. soldiers. Spooked by an earlier incident, the soldiers fired shots at the vehicle, striking Safa through the head. Although not quite dead when soldiers found her, no medical assistance was called because of the severity of her wound, and Safa died a few minutes later.

Safa is one of innumerable and largely unrecognizanced victims of the the U.S. invasion. Like those killed in the Hadytha massacre, or countless checkpoints shootings, or in the first and second battles for Falllujah.

These are the stories of the numbers of the dead found the PLoS study. These stories are multiplied by a hundred, by a thousand, by a hundred-thousand, and two hundred thousand, and we begin to approach the meaning of the study.

The Right to Heal

There have been efforts to reach out to Iraqi victims and their families on the part of U.S service members. Following the release of the Wikileaks "Collateral Murder" video, two veterans, Josh Stieber and Ethan McCord, wrote "An Open Letter of Reconciliation and Responsibility to the Iraqi People," in which they apologized for the crimes they participated in, and sought dialogue with Iraqis.

In March of this year, on the tenth anniversary of the U.S. invasion, the Organization of Women's Freedom in Iraq (OWFI), Iraq Veterans Against the War (IVAW), and the Federation of Workers Councils and Unions in Iraq (FWCUI) launched the Right to Heal Initiative. From their website:

Iraqis and veterans are coming together to hold the U.S. government accountable for the lasting effects of war and the rights of veterans and civilians to heal. The Iraq war is not over for Iraqi civilians and U.S. veterans who continue to struggle with various forms of trauma and injury; the effects of environmental poisoning due to certain U.S. munitions and burn pits of hazardous materials; and with a generation of orphans and displaced. As Iraqi civil society tries to rebuild from the Iraq war as well as a decade of U.S. bombing and sanctions, they face political repression by a corrupt U.S.-established government that is selling off the country's natural resources to foreign interests.

Along with the Center for Constitutional Rights, these groups have filed a request for a hearing with the Inter-American Commission for Human Rights.

These efforts by veteran and human rights groups need to be supported. Even with withdrawal of U.S. combat troops, Iraqis continue to live and die because of the impacts of the invasion of their country of which the car bombing last Saturday is just one incident. The PLoS-Medicine study published today helps us understand some of those impacts.