Writing for his October 25, 2013 New York Times column, Paul Krugman noted the attraction that apocalyptic scenarios had for American investors, policy makers, and economists. He named Alan Simpson and Erskine Bowles as "deficit-scolds" whose doomsaying has been overwrought, and he reprised a 2010 article by Alan Greenspan in which the former Chairman of the Federal Reserve warned that the national budget deficit would lead to soaring inflation and interest rates, trends that we have not yet seen.

Mr. Krugman is an economist so it is understandable that it would be the scaremongers in his own area of expertise that catch his attention. His concern that the "debt-apocalypse community," as he calls it, includes powerful people whose technical judgment might be clouded by irrational fears is legitimate. A single policy enunciation by any one of them, after all, can make or break the life-chances of millions of people around the globe.

But left as it is by his column, Krugman appears to think some gentle teasing like his--he calls his mistaken peers "Chicken Littles"--might diminish the credibility of the end-of-time crowd in the arena of public opinion, if not actually disabusing them of their fantasies. He also assures his readers that they needn't fear an ultimate final collapse, a "fiscal apocalypse," such as that warned of by the fear-peddlers he names.

He says all this as if the prophets of national cataclysm have arrived from another planet with a message that is totally alien to the populace hearing it. In fact, the real relationship between the people, cultural apocalypticism, and the elites whose rhetoric associate them with it is something closer to the inverse of what Krugman implies.

One need look no further than the titles of movies and books produced over the last fifteen years to see the extent of apocalyptic themes in American popular culture. One search of film titles returned over 900 such references including those to Apocalypse 2012: The World after Time Ends, Apocalypse: World War II, and Zombie Apocalypse 2012, all made in the new century. Playing on the theme, films like the very popular Apocalypto made in 2006 by Mel Gibson broadened the audience for that imagery, as did television documentaries like Doomsday Preppers about people preparing for the end of the world. By some count, the end-of-time book series known as Left Behind, about those "raptured" to the after-life and those left behind, was the largest selling book series of all time.

In the last five years, the New York Times alone has used the word "apocalypse" in news stories more than 1,100 times.

Culture-critics attuned to these currents would easily recognize that the policy elites that Krugman is critical of are not responsible for the fear and anxiety expressed by many Americans about the insecurity in their lives--the people have their own sources of that, thank you. Rather, the elites are smartly feeding into a thick and deep vein of uncertainty running through the country wherein they know their forecasts of fiscal collapse will find resonance.

Krugman's Times piece carried the title "Addicted to the Apocalypse"; understanding that "addiction" as a socio-cultural malady, rather than a fixation of professors and pundits, does not diminish it as a cause for concern. Indeed, the history of mischief that has come out of the nihilist impulse in apocalyptic imagery--think Nazi Germany--underscore the importance of an inquiry into the American iteration of those ideas.

Visions of the apocalypse are a staple element of fundamentalist readings of the Bible's Book of Revelation. From time to time, throughout the colonial period and the early centuries of the nation, they manifested in periods of rapid social change and religious revivalism that sometimes spawned fears of betrayal by enemy aliens masquerading as patriots. After the McCarthy-ite hysteria of the 1950s, however, those religious undertones faded into the backstory of America's political history.

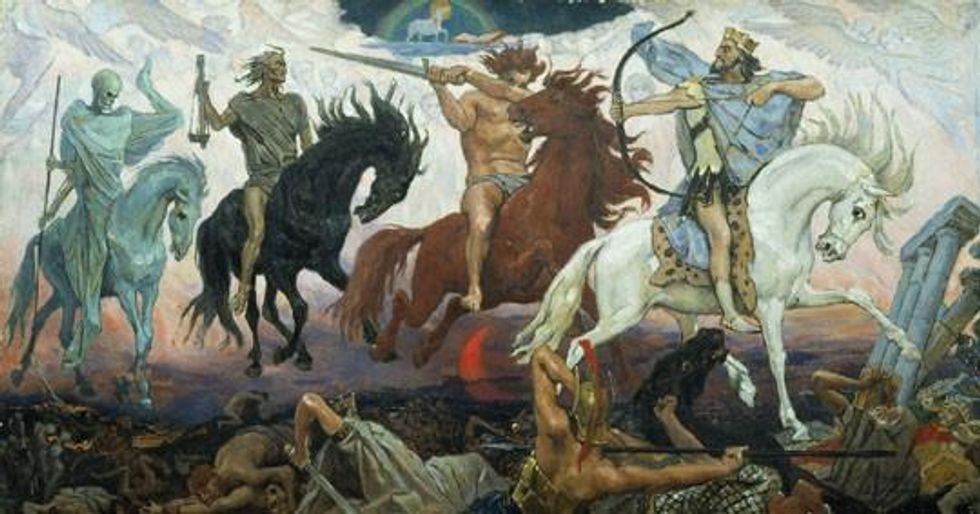

Americans growing up in the late 1950s and early 1960s would have heard the word "apocalypse" only in a religion-education class, if at all. The 1921 silent film Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse was remade for a 1962 release but it had little to do with religion or politics. The New York Times uses of the word in any context between 1955 and 1965 numbered exactly zero. Between 1965 and 1975 it appeared in 21 stories but then increase in use over the next ten years to 369. The American fascination with the end-of-time had begun.

Given the influence that apocalypticism exercises in our political culture it behooves us to understand why it gripped the national mindset when it did.

Film buffs are likely to suggest that it was a cultural phenomenon induced by the 1978 film Apocalypse Now: set in Vietnam, with a story-line about conspiratorial government and military infighting, it ended in a fireball, with everything blown to bits. In as much as that film by Francis Ford Coppola was popular and won two Academy Awards, film fans are right--it certainly added "apocalypse" to my vocabulary. But what had put the notion on the film maker's mind and made him think that theater-goers could be drawn to it?

Just as the economic thinkers that Krugman writes about are less the instigators of a trend than exploiters of it, so too the national mood forming around the resentments, anger, and suspicions about the loss of the war in Vietnam had been underway for ten years before Coppola's film came out. The first Times use of "apocalypse" in that context came just a year after the U.S. was fought to a draw in the 1968 Tet Offensive. Shortly thereafter, in October, 1970, the Times reviewed Theater of the Apocalypse, produced by anti-war activist Abbie Hoffman, and followed with stories about environmental destruction that widened the imaginable of the erstwhile unimaginable in the years that preceded Apocalypse Now.

The short-form on the revivified apocalyptic imagery in modern America is that it was born-again and cradled in the culture of military defeat, loss of national pride, and anxiety about the future that followed the War in Vietnam. Today's apocalyticism is an end-of-empire phenomenon emanating from homes, workplaces, farms, and places of worship, cultivated by Hollywood since the 1970s, and nurtured by the neo-conservative witch-hunt for radicals and liberals responsible for the loss of the war-at-home during the 1980s and 1990s that has grown, now, to become the dominant American political narrative.

Krugman calls our attention to that narrative but it would be a mistake to think that by calling-out policy makers for their fear-mongering, the concern is allayed. The emotional appeal of the paranoia and nihilism that is implicit in the end-of-time fantasies conjured by their forecasts is a match waiting to be struck; the social conditions wrought by job loss, broken institutions, and the declining global stature of the America once imagined by its masses to be their "City on the Hill" is kindling waiting to burn.

Economists, we hope, can inform policies that mitigate, at least, the conditions giving rise to the despair preyed upon by the demagogues of doom. But, as revealed in Krugman's column, even the best of them, as he certainly is, labor within the narrowness of their own professional and institutional boundaries. The work of historians, political scientists, and culture-critics is similarly constrained.

The crisis of America today is societal, its understanding requiring the full range of academic social science and humanities together with efforts of journalists and culture-makers in an approach that is yet holistic enough to transcend even the totality of what the experts in those fields can bring.

It's a time for big ideas and the people who think them.