World Bank economist Branko Milanovic does serious work. His explorations into global income distribution have won him a wide -- and appreciative -- audience in scholarly and policy-making circles all the world over.

But Milanovic isn't always crunching data and writing up insightful articles and books. In fact, Milanovic likes to have a good time as much as anyone. He may even rate, in some people's eyes, as a fun sort of guy.

Recently, in a light-hearted moment, Milanovic brought his two passions together and came up with a new yardstick for human progress, a cross-national international index for measuring "funness."

This "funness" index, Milanovic acknowledges, "started as a joke." The world has "all kinds of international indexes," as he told an Australian journalist earlier this fall. We should have one, he thought, "that explores fun."

But the joke soon turned intellectually interesting. What does, after all, make one society more fun to live in than another?

Milanovic would eventually work up a list of ten basic factors than encourage good times. Some of his "elements" would be rather obvious. Fun places, as the Milanovic yardstick recognizes, have "lots of restaurants and good nightlife."

Other elements on the Milanovic list turn out to be far more edgy. Fun places, Milanovic writes, have a "slight decadence floating in the air" -- and "frequent changes in government." How do changes in government help people have fun? They give people, Milanovic explains, plenty of "topics to talk about."

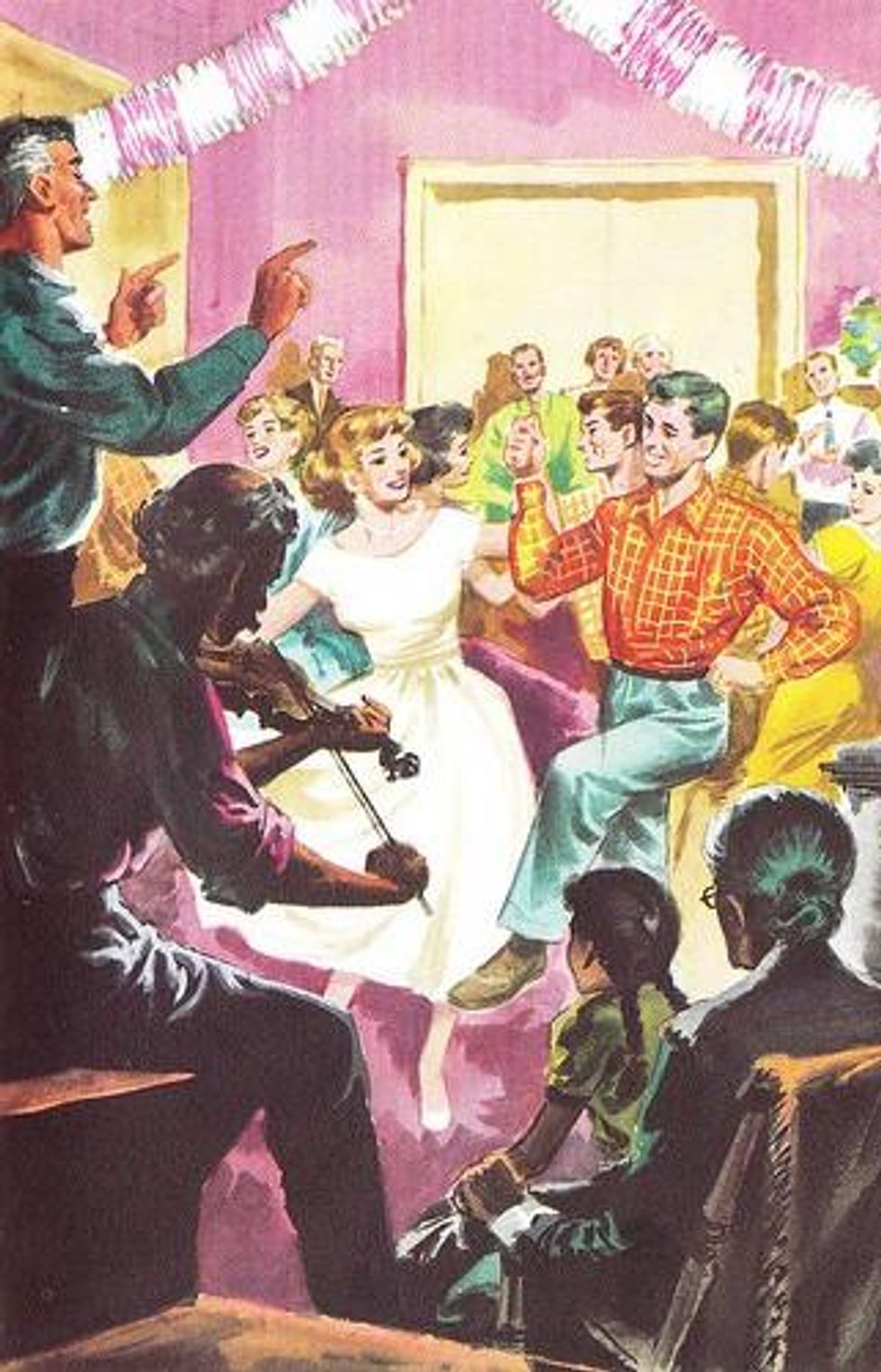

But truly fun societies, Milanovic ends up stressing, have more than hot spots and hot topics. They have "low inequality and small differences in social status."

"I think people treat each other better in societies that do not have very rigid social divisions and distinctions," comments Milanovic. "You have more fun in places where people treat each other well."

Fun societies have low inequality and small differences in social status.

How specifically does inequality turn savagely unequal societies into party-pooping places? Milanovic doesn't delve too deeply into specifics with his "funness" index. He does offer one anecdotal example. If you come out of a restaurant after a great meal and have "20 people asking you for money," Milanovic suggests, that's probably going to "spoil your fun."

Other chroniclers of our unequal times have actually gone far more deeply into this fun phenomenon, most notably the journalist Michelle Quinn.

Back in 1999, at the height of the dot.com bubble, Quinn did a powerful series of articles in the San Jose Mercury News, the hometown paper of California's Silicon Valley. Her focus: the street-level impact of the high tech industry's incredibly unequal distribution of rewards.

"Economic disparity," Quinn would note in her reporting, "has always made socializing awkward."

Economic disparities have always made socializing awkward.

This awkwardness, her reporting detailed, can spoil even the most casual of encounters. Just going about "picking a restaurant to meet friends," Quinn related, can end up sparking considerable social static if some acquaintances in a group can easily afford a hot new dinner spot and others can't.

Wealthy people, once singed by such static, tend to take steps to avoid it in the future. They start, sometimes consciously, sometimes not, only "making friends with those whose economic profile is similar to theirs."

In the process, old social circles shrink and crumble. Daily life becomes ever more stratified -- and stressful.

Girls and boys who really do just want to have fun might be wise to keep all these dynamics in mind. The narrower the gaps that divide us, the better the chances that good times are going to be rolling.