SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

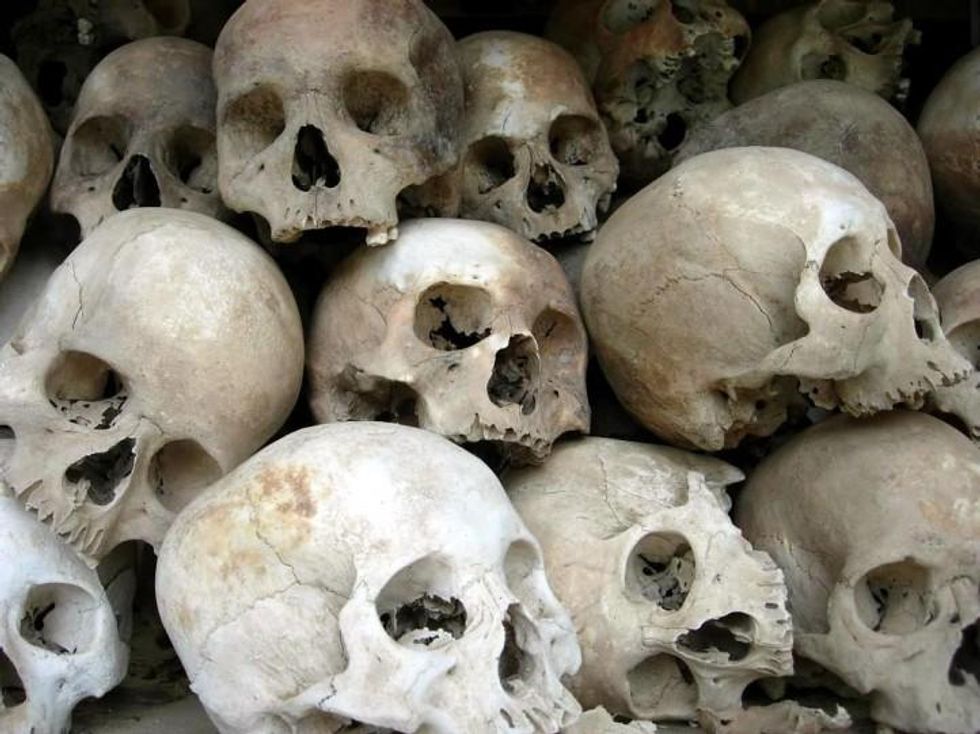

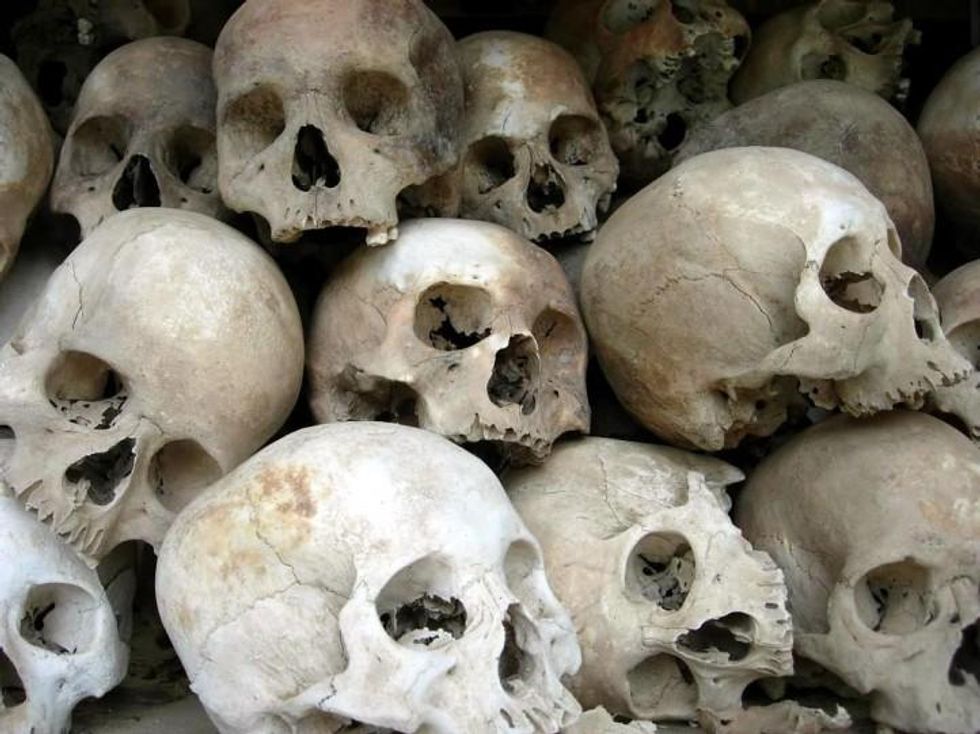

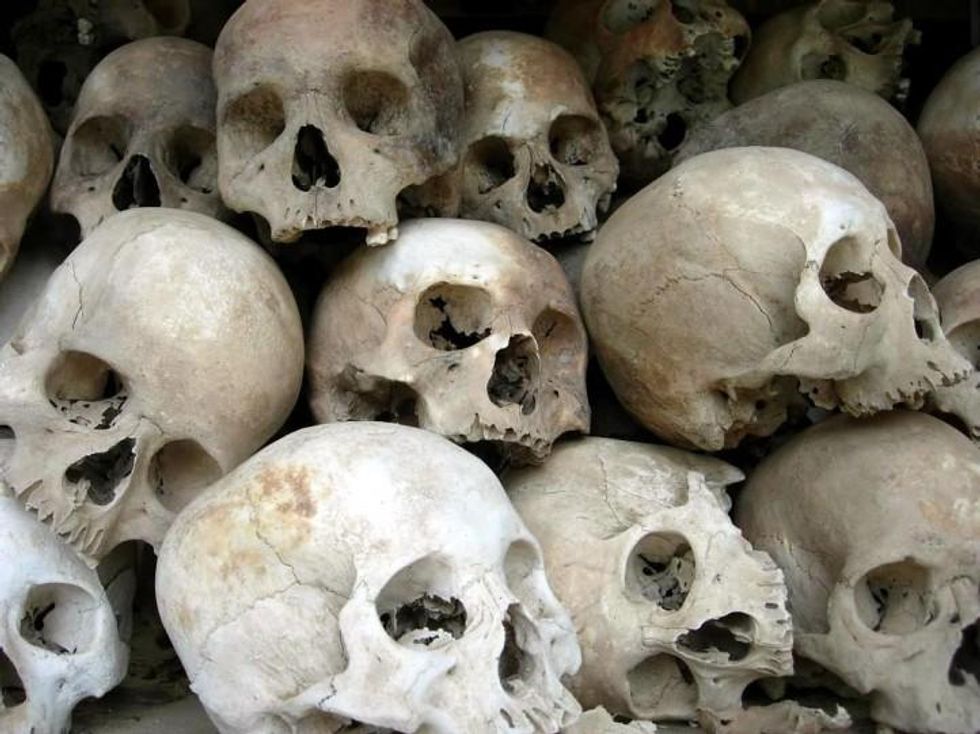

Today marks the 65th anniversary of the Genocide Convention, the groundbreaking United Nations document that declared genocide to be an international crime.

Why?

The most frequent explanations for America's failure to prevent genocide concern a lack of national interest or political will. Both have indeed been influential. But a more honest account would acknowledge the United States' own complicity in backing genocidal regimes.

It's time for the United States to examine how its own foreign policy promotes genocide, and take the actions necessary to curb it. These include making clear assessments of when genocide is occurring or about to occur -- regardless of whether it is perpetrated by its friends or foes -- and granting jurisdiction to the International Court of Justice (ICJ), the body designated by the resolution to hear "disputes between the Contracting Parties relating to the interpretation, application, or fulfillment of the present Convention, including those relating to the responsibility of a State for genocide."

A Convention against Genocide

The United Nations General Assembly adopted the resolution -- formally called the Convention for the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide -- in 1948, and the law entered into force in 1951.

The convention defines genocide as actions taken with the "intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial, or religious group." In contrast to the designation of "crimes against humanity," which were at that time understood to happen only during war, the convention broke new ground in noting that genocide can also occur in peacetime -- thus opening a broader set of acts of violence to international condemnation. The convention identified genocide as a crime under international law, outlined the specific criminal acts that constituted it, and called for cooperation among ratifying nations to stop it.

Eventually, cases for the Genocide Convention came to be tried before the ICJ in The Hague, Netherlands.

The United States became a signatory to this convention in 1948, but resisted passing the legislation to implement it until 1988. Moreover, the United States is one of only five parties to the Genocide Convention that refuse to recognize the jurisdiction of the ICJ. Although it had signed on 40 years earlier, the United States withdrew its agreement to compulsory jurisdiction by the ICJ in 1986, when Nicaragua brought a case against the United States for sponsoring an insurrection against the Nicaraguan government. The United States' lack of participation in the full authority of the ICJ directly diminishes the court's ability to hold states accountable for violations of international laws and norms, and diminishes the world's ability to prevent genocide.

National Interest and Political Will

Two main reasons have been given for the United States' failure to prevent genocide: national interest and political will.

Although awash in lofty rhetoric about human rights and democracy, the United States often pursues what it sees as its own best interest. Frequently this amounts to a calculation based on its relations with individual members of the international community: When enemy states commit massacres, the United States responds with condemnation, sanctions, and possibly military intervention. In contrast, when the perpetrator of serious human rights violations is a U.S. client state, the United States remains silent -- or, at most, issues an occasional rhetorical condemnation.

The "political will" narrative suggests that the country's heart is in the right place but that policymakers are prevented by domestic political considerations from taking the necessary action to stop genocide. In their 2008 report on the occasion of the 60th anniversary of the Genocide Convention, "Preventing Genocide: A Blueprint for U.S. Policymakers," Madeleine Albright and William Cohen made this argument forcefully, repeatedly calling for improved leadership and political will.

But the story of America's relationship with genocide is far more than a case of purposeful negligence. The United States has had close ties with numerous genocidal regimes, despite being a signatory to the Genocide Convention.

Selective Outrage and Complicity

Years of massacres around the world demonstrate Washington's selective outrage: condemnation of certain atrocities and silence or complicity toward others.

One of the most famous cases of the United States remaining silent occurred in 1971. On March 25, the regime based in West Pakistan launched "Operation Searchlight," which initiated its genocide against Bengalis in East Pakistan (present day Bangladesh). Acting with the courage to challenge his own government, Arthur Blood, at the time the U.S. general consul in Dhaka, sent what came to be known as the "Blood Telegram." In it, he and others criticized the U.S. government for failing to denounce Pakistan's "genocide" and for choosing "not to intervene, even morally."

This silence in the face of massacre can be explained by geopolitics. At the time, the United States and China were using Pakistan as an intermediary in their attempt to open and improve Sino-American relations. Despite Blood's passionate insistence that genocide was taking place, the Nixon administration refused to use the word "genocide" to describe the atrocities. Doing so would have implied an obligation to intervene under the Genocide Convention and undermined the administration's geopolitical goals.

Halfway around the world and a decade later, the United States not only fell silent, but actively supported a government while it was committing genocide. Following Efrain Rios Montt's military coup in March 1982, the Guatemalan army massacred indigenous Mayan villagers deemed sympathetic towards leftist rebels. The suppression of left-wing activity fit squarely with U.S. goals during the Cold War. When the Commission for Historical Clarification presented its final report, Guatemala: Memory of Silence, in 1999, it found that 83 percent of the victims had been Mayan and concluded that "agents of the state committed acts of genocide against groups of Mayan people."

The Reagan administration had been no passive bystander in this crime. During Rios Montt's recent trial on charges of genocide, award-winning journalist Allan Nairn reminded us that "U.S. military attaches in Guatemala, the CIA people who were on the ground aiding the G2 military intelligence unit, [and] the policy-making officials back in Washington...were direct accessories to and accomplices to the Guatemalan military. They were supplying money, weapons, political support, intelligence." Far from standing silently by, the United States directly supported those committing the atrocities in order to achieve its own Cold War goals.

A mere six years later, the Reagan administration once again gave support to a genocidal regime--this time Saddam Hussein's Iraq. Despite the fact that Washington had facilitated arms transfers to Iran during the Iran-Contra affair, the Reagan administration did not want Iraq to lose in its war with Iran, which raged throughout the 1980s and claimed over a million lives. Despite knowing full well that the Iraqi leader had used chemical weapons to commit genocide against Iraq's Kurdish population, U.S. government officials continued to support Hussein. According to journalist Mike Shuster, in the 1980s the United States "play[ed] a key role in all of [Hussein's] actions, military and political." Hussein, according to Shuster, "was meeting with senior U.S. diplomats. They were looking the other way when he was using chemical weapons and developing other unconventional weapons. He couldn't have helped but to think that the United States was behind him." And so once again, geopolitical considerations led the United States to back a dictator engaged in genocide.

Over two decades later, the Obama administration has similarly maintained relations with genocidal regimes. In 2010, a leaked UN report alleged that Rwanda, under current president Paul Kagame, may have committed a reprisal genocide against ethnic Hutus who had taken refuge in the neighboring DRC. More recently, Rwanda has been accused of having direct control over the Congolese M23 rebel group, which UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Navy Pillay called "among the worst perpetrators of human rights violations in the DRC, or in the world." But Paul Kagame has maintained close relations with the United States ever since the 1994 genocide, and Rwanda remains a strategic ally for the United States in central Africa.

A similar drama may be unfolding in Myanmar, where Muslim Rohingya villagers have been denied their right to citizenship and targeted by Buddhist mobs and sympathetic security forces as part of a campaign to ethnically cleanse Myanmar of its Rohingya population. According to Human Rights Watch, "An ethnic Arakanese campaign of violence and abuses since June 2012 facilitated by and at times involving state security forces and government officials has displaced more than 125,000 Rohingya and Kaman Muslims in western Burma's Arakan State. Tens of thousands of Rohingya still lack adequate humanitarian aid - leading to an unknown number of preventable deaths - in isolated, squalid displacement camps."

The systematic nature of these abuses -- and the involvement of Myanmar officials -- constitutes crimes against humanity as defined by the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. Further, if the intent behind the policy of isolating Rohingya in camps and denying them access to humanitarian aid is their eventual death, Myanmar's crimes could elevate to genocide under Article 2 of the Genocide Convention, which includes "deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part."

Ahamed Jarmal, Secretary General of the Burmese Rohingya Organization, recently warned that "the situation is getting really desperate. Mobs have attacked our villages, driving us from our homes, children have been hacked to death, and hundreds of my people have been killed by members of the majority. Thugs are distributing leaflets threatening to 'wipe us out' and children in schools are being taught that the Rohingya are different." Yet minor democratic reforms and the release of some political prisoners were rewarded with the lifting of sanctions and visits to Myanmar by then Secretary of State Clinton, as well as President Obama. More recently, President Obama welcomed Myanmar president Thein Sein to the United States.

In November 2012, prior to President Obama's visit to Myanmar, U.S. Ambassador to the UN Samantha Power wrote glowingly of the Obama administration's support for human rights in Myanmar and the reforms already underway. Yet Power also tempered the praise, warning that "We are clear-eyed about the challenges that Burma faces. The peril faced by the stateless Rohingya population in Rakhine State is particularly urgent, and we have joined the international community in expressing deep concern about recent violence that has left hundreds dead, displaced over 110,000, and destroyed thousands of homes."

More than a year later, conditions for the Rohingya have worsened. Yet U.S. policy stays the course, a classic exemplification of the foreign policy of selective outrage. Myanmar is committing crimes against humanity, yet is rewarded with the lifting of sanctions and presidential visits. The good treatment is no wonder: resource-rich Myanmar holds economic opportunities for the United States and is strategically located on China's southwestern border.

The United States does not have a policy of disengagement when it comes to the prevention of genocide. Rather, U.S. policy is far worse: it operates on a principle of direct engagement with -- and sometimes support of -- genocidal regimes when Washington's geopolitical goals demand it.

Prevention

The Genocide Convention requires not only that perpetrators of genocide be held to account, but also that countries prevent genocide from occurring in the first place.

In 2007, the ICJ ruled in the case of Bosnia v. Serbia that Serbia failed to fulfill its obligation under the Genocide Convention to prevent genocide. According to the ICJ, "In view of their undeniable influence," the Yugoslav federal authorities should "have made the best efforts within their power to try and prevent the tragic events then taking shape, whose scale, though it could not have been foreseen with certainty, might at least have been surmised." The ICJ ruled that Serbia had the necessary influence over the Bosnian Serbs to at least attempt to use that influence to deter the Bosnian Serbs from committing genocide against Bosnian Muslims.

What about the United States? Did it wield the necessary influence over the Pakistani, Guatemalan, and Iraqi governments to have failed to fulfill its own obligation to prevent genocide? Does the Obama administration hold the necessary influence in Rwanda and Myanmar today?

Vera Saeedpour, the late Kurdish specialist, once lamented that "Until the priorities of the international community are reordered to place human life in a loftier position, I fear that our efforts will be largely relegated to recording atrocities in history books." The universal eradication of genocide and other mass atrocity crimes requires a revolutionary change in philosophy 3/4 one that elevates human life above the national interest.

A good first step would be to redefine protecting human life as a national interest. President Barack Obama intimated as much two years ago when he presented his "Presidential Study Directive on Mass Atrocities." He said at the time, "Preventing mass atrocities and genocide is a core national security interest and a core moral responsibility of the United States. Our security is affected when masses of civilians are slaughtered, refugees flow across borders, and murderers wreak havoc on regional stability and livelihoods. America's reputation suffers, and our ability to bring about change is constrained, when we are perceived as idle in the face of mass atrocities and genocide."

Obama went on to create an "interagency Atrocities Prevention Board" to "coordinate a whole of government approach to preventing mass atrocities and genocide." Human rights groups have generally welcomed this development, but have recommended that the administration publicly state what the comprehensive strategy for preventing atrocities is, improve transparency, consult with civil society groups and Congress, coordinate its efforts internationally, address actual emergencies in the world, and make sure the board has the resources to be effective.

But the problems go much deeper. To have true effect, such a task force would need to recognize when genocide has been -- or is about to be -- perpetrated by countries the United States considers allies. Even further, it would need to take seriously the United States' own complicity in genocide -- and commit to preventing it by transforming U.S. foreign policy.

Nothing can excuse the outrageous failure to prevent genocide. The United States needs to stop selectively condemning countries only when it is in its own supposed interest to do so. It needs to create a uniform standard for condemning human rights violations. And it needs to recognize the jurisdiction of the ICJ, as well as the International Criminal Court. If that means taking responsibility -- and risk -- for being held to account for its own violations of human rights, then all the better.

___________________

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

Today marks the 65th anniversary of the Genocide Convention, the groundbreaking United Nations document that declared genocide to be an international crime.

Why?

The most frequent explanations for America's failure to prevent genocide concern a lack of national interest or political will. Both have indeed been influential. But a more honest account would acknowledge the United States' own complicity in backing genocidal regimes.

It's time for the United States to examine how its own foreign policy promotes genocide, and take the actions necessary to curb it. These include making clear assessments of when genocide is occurring or about to occur -- regardless of whether it is perpetrated by its friends or foes -- and granting jurisdiction to the International Court of Justice (ICJ), the body designated by the resolution to hear "disputes between the Contracting Parties relating to the interpretation, application, or fulfillment of the present Convention, including those relating to the responsibility of a State for genocide."

A Convention against Genocide

The United Nations General Assembly adopted the resolution -- formally called the Convention for the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide -- in 1948, and the law entered into force in 1951.

The convention defines genocide as actions taken with the "intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial, or religious group." In contrast to the designation of "crimes against humanity," which were at that time understood to happen only during war, the convention broke new ground in noting that genocide can also occur in peacetime -- thus opening a broader set of acts of violence to international condemnation. The convention identified genocide as a crime under international law, outlined the specific criminal acts that constituted it, and called for cooperation among ratifying nations to stop it.

Eventually, cases for the Genocide Convention came to be tried before the ICJ in The Hague, Netherlands.

The United States became a signatory to this convention in 1948, but resisted passing the legislation to implement it until 1988. Moreover, the United States is one of only five parties to the Genocide Convention that refuse to recognize the jurisdiction of the ICJ. Although it had signed on 40 years earlier, the United States withdrew its agreement to compulsory jurisdiction by the ICJ in 1986, when Nicaragua brought a case against the United States for sponsoring an insurrection against the Nicaraguan government. The United States' lack of participation in the full authority of the ICJ directly diminishes the court's ability to hold states accountable for violations of international laws and norms, and diminishes the world's ability to prevent genocide.

National Interest and Political Will

Two main reasons have been given for the United States' failure to prevent genocide: national interest and political will.

Although awash in lofty rhetoric about human rights and democracy, the United States often pursues what it sees as its own best interest. Frequently this amounts to a calculation based on its relations with individual members of the international community: When enemy states commit massacres, the United States responds with condemnation, sanctions, and possibly military intervention. In contrast, when the perpetrator of serious human rights violations is a U.S. client state, the United States remains silent -- or, at most, issues an occasional rhetorical condemnation.

The "political will" narrative suggests that the country's heart is in the right place but that policymakers are prevented by domestic political considerations from taking the necessary action to stop genocide. In their 2008 report on the occasion of the 60th anniversary of the Genocide Convention, "Preventing Genocide: A Blueprint for U.S. Policymakers," Madeleine Albright and William Cohen made this argument forcefully, repeatedly calling for improved leadership and political will.

But the story of America's relationship with genocide is far more than a case of purposeful negligence. The United States has had close ties with numerous genocidal regimes, despite being a signatory to the Genocide Convention.

Selective Outrage and Complicity

Years of massacres around the world demonstrate Washington's selective outrage: condemnation of certain atrocities and silence or complicity toward others.

One of the most famous cases of the United States remaining silent occurred in 1971. On March 25, the regime based in West Pakistan launched "Operation Searchlight," which initiated its genocide against Bengalis in East Pakistan (present day Bangladesh). Acting with the courage to challenge his own government, Arthur Blood, at the time the U.S. general consul in Dhaka, sent what came to be known as the "Blood Telegram." In it, he and others criticized the U.S. government for failing to denounce Pakistan's "genocide" and for choosing "not to intervene, even morally."

This silence in the face of massacre can be explained by geopolitics. At the time, the United States and China were using Pakistan as an intermediary in their attempt to open and improve Sino-American relations. Despite Blood's passionate insistence that genocide was taking place, the Nixon administration refused to use the word "genocide" to describe the atrocities. Doing so would have implied an obligation to intervene under the Genocide Convention and undermined the administration's geopolitical goals.

Halfway around the world and a decade later, the United States not only fell silent, but actively supported a government while it was committing genocide. Following Efrain Rios Montt's military coup in March 1982, the Guatemalan army massacred indigenous Mayan villagers deemed sympathetic towards leftist rebels. The suppression of left-wing activity fit squarely with U.S. goals during the Cold War. When the Commission for Historical Clarification presented its final report, Guatemala: Memory of Silence, in 1999, it found that 83 percent of the victims had been Mayan and concluded that "agents of the state committed acts of genocide against groups of Mayan people."

The Reagan administration had been no passive bystander in this crime. During Rios Montt's recent trial on charges of genocide, award-winning journalist Allan Nairn reminded us that "U.S. military attaches in Guatemala, the CIA people who were on the ground aiding the G2 military intelligence unit, [and] the policy-making officials back in Washington...were direct accessories to and accomplices to the Guatemalan military. They were supplying money, weapons, political support, intelligence." Far from standing silently by, the United States directly supported those committing the atrocities in order to achieve its own Cold War goals.

A mere six years later, the Reagan administration once again gave support to a genocidal regime--this time Saddam Hussein's Iraq. Despite the fact that Washington had facilitated arms transfers to Iran during the Iran-Contra affair, the Reagan administration did not want Iraq to lose in its war with Iran, which raged throughout the 1980s and claimed over a million lives. Despite knowing full well that the Iraqi leader had used chemical weapons to commit genocide against Iraq's Kurdish population, U.S. government officials continued to support Hussein. According to journalist Mike Shuster, in the 1980s the United States "play[ed] a key role in all of [Hussein's] actions, military and political." Hussein, according to Shuster, "was meeting with senior U.S. diplomats. They were looking the other way when he was using chemical weapons and developing other unconventional weapons. He couldn't have helped but to think that the United States was behind him." And so once again, geopolitical considerations led the United States to back a dictator engaged in genocide.

Over two decades later, the Obama administration has similarly maintained relations with genocidal regimes. In 2010, a leaked UN report alleged that Rwanda, under current president Paul Kagame, may have committed a reprisal genocide against ethnic Hutus who had taken refuge in the neighboring DRC. More recently, Rwanda has been accused of having direct control over the Congolese M23 rebel group, which UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Navy Pillay called "among the worst perpetrators of human rights violations in the DRC, or in the world." But Paul Kagame has maintained close relations with the United States ever since the 1994 genocide, and Rwanda remains a strategic ally for the United States in central Africa.

A similar drama may be unfolding in Myanmar, where Muslim Rohingya villagers have been denied their right to citizenship and targeted by Buddhist mobs and sympathetic security forces as part of a campaign to ethnically cleanse Myanmar of its Rohingya population. According to Human Rights Watch, "An ethnic Arakanese campaign of violence and abuses since June 2012 facilitated by and at times involving state security forces and government officials has displaced more than 125,000 Rohingya and Kaman Muslims in western Burma's Arakan State. Tens of thousands of Rohingya still lack adequate humanitarian aid - leading to an unknown number of preventable deaths - in isolated, squalid displacement camps."

The systematic nature of these abuses -- and the involvement of Myanmar officials -- constitutes crimes against humanity as defined by the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. Further, if the intent behind the policy of isolating Rohingya in camps and denying them access to humanitarian aid is their eventual death, Myanmar's crimes could elevate to genocide under Article 2 of the Genocide Convention, which includes "deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part."

Ahamed Jarmal, Secretary General of the Burmese Rohingya Organization, recently warned that "the situation is getting really desperate. Mobs have attacked our villages, driving us from our homes, children have been hacked to death, and hundreds of my people have been killed by members of the majority. Thugs are distributing leaflets threatening to 'wipe us out' and children in schools are being taught that the Rohingya are different." Yet minor democratic reforms and the release of some political prisoners were rewarded with the lifting of sanctions and visits to Myanmar by then Secretary of State Clinton, as well as President Obama. More recently, President Obama welcomed Myanmar president Thein Sein to the United States.

In November 2012, prior to President Obama's visit to Myanmar, U.S. Ambassador to the UN Samantha Power wrote glowingly of the Obama administration's support for human rights in Myanmar and the reforms already underway. Yet Power also tempered the praise, warning that "We are clear-eyed about the challenges that Burma faces. The peril faced by the stateless Rohingya population in Rakhine State is particularly urgent, and we have joined the international community in expressing deep concern about recent violence that has left hundreds dead, displaced over 110,000, and destroyed thousands of homes."

More than a year later, conditions for the Rohingya have worsened. Yet U.S. policy stays the course, a classic exemplification of the foreign policy of selective outrage. Myanmar is committing crimes against humanity, yet is rewarded with the lifting of sanctions and presidential visits. The good treatment is no wonder: resource-rich Myanmar holds economic opportunities for the United States and is strategically located on China's southwestern border.

The United States does not have a policy of disengagement when it comes to the prevention of genocide. Rather, U.S. policy is far worse: it operates on a principle of direct engagement with -- and sometimes support of -- genocidal regimes when Washington's geopolitical goals demand it.

Prevention

The Genocide Convention requires not only that perpetrators of genocide be held to account, but also that countries prevent genocide from occurring in the first place.

In 2007, the ICJ ruled in the case of Bosnia v. Serbia that Serbia failed to fulfill its obligation under the Genocide Convention to prevent genocide. According to the ICJ, "In view of their undeniable influence," the Yugoslav federal authorities should "have made the best efforts within their power to try and prevent the tragic events then taking shape, whose scale, though it could not have been foreseen with certainty, might at least have been surmised." The ICJ ruled that Serbia had the necessary influence over the Bosnian Serbs to at least attempt to use that influence to deter the Bosnian Serbs from committing genocide against Bosnian Muslims.

What about the United States? Did it wield the necessary influence over the Pakistani, Guatemalan, and Iraqi governments to have failed to fulfill its own obligation to prevent genocide? Does the Obama administration hold the necessary influence in Rwanda and Myanmar today?

Vera Saeedpour, the late Kurdish specialist, once lamented that "Until the priorities of the international community are reordered to place human life in a loftier position, I fear that our efforts will be largely relegated to recording atrocities in history books." The universal eradication of genocide and other mass atrocity crimes requires a revolutionary change in philosophy 3/4 one that elevates human life above the national interest.

A good first step would be to redefine protecting human life as a national interest. President Barack Obama intimated as much two years ago when he presented his "Presidential Study Directive on Mass Atrocities." He said at the time, "Preventing mass atrocities and genocide is a core national security interest and a core moral responsibility of the United States. Our security is affected when masses of civilians are slaughtered, refugees flow across borders, and murderers wreak havoc on regional stability and livelihoods. America's reputation suffers, and our ability to bring about change is constrained, when we are perceived as idle in the face of mass atrocities and genocide."

Obama went on to create an "interagency Atrocities Prevention Board" to "coordinate a whole of government approach to preventing mass atrocities and genocide." Human rights groups have generally welcomed this development, but have recommended that the administration publicly state what the comprehensive strategy for preventing atrocities is, improve transparency, consult with civil society groups and Congress, coordinate its efforts internationally, address actual emergencies in the world, and make sure the board has the resources to be effective.

But the problems go much deeper. To have true effect, such a task force would need to recognize when genocide has been -- or is about to be -- perpetrated by countries the United States considers allies. Even further, it would need to take seriously the United States' own complicity in genocide -- and commit to preventing it by transforming U.S. foreign policy.

Nothing can excuse the outrageous failure to prevent genocide. The United States needs to stop selectively condemning countries only when it is in its own supposed interest to do so. It needs to create a uniform standard for condemning human rights violations. And it needs to recognize the jurisdiction of the ICJ, as well as the International Criminal Court. If that means taking responsibility -- and risk -- for being held to account for its own violations of human rights, then all the better.

___________________

Today marks the 65th anniversary of the Genocide Convention, the groundbreaking United Nations document that declared genocide to be an international crime.

Why?

The most frequent explanations for America's failure to prevent genocide concern a lack of national interest or political will. Both have indeed been influential. But a more honest account would acknowledge the United States' own complicity in backing genocidal regimes.

It's time for the United States to examine how its own foreign policy promotes genocide, and take the actions necessary to curb it. These include making clear assessments of when genocide is occurring or about to occur -- regardless of whether it is perpetrated by its friends or foes -- and granting jurisdiction to the International Court of Justice (ICJ), the body designated by the resolution to hear "disputes between the Contracting Parties relating to the interpretation, application, or fulfillment of the present Convention, including those relating to the responsibility of a State for genocide."

A Convention against Genocide

The United Nations General Assembly adopted the resolution -- formally called the Convention for the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide -- in 1948, and the law entered into force in 1951.

The convention defines genocide as actions taken with the "intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial, or religious group." In contrast to the designation of "crimes against humanity," which were at that time understood to happen only during war, the convention broke new ground in noting that genocide can also occur in peacetime -- thus opening a broader set of acts of violence to international condemnation. The convention identified genocide as a crime under international law, outlined the specific criminal acts that constituted it, and called for cooperation among ratifying nations to stop it.

Eventually, cases for the Genocide Convention came to be tried before the ICJ in The Hague, Netherlands.

The United States became a signatory to this convention in 1948, but resisted passing the legislation to implement it until 1988. Moreover, the United States is one of only five parties to the Genocide Convention that refuse to recognize the jurisdiction of the ICJ. Although it had signed on 40 years earlier, the United States withdrew its agreement to compulsory jurisdiction by the ICJ in 1986, when Nicaragua brought a case against the United States for sponsoring an insurrection against the Nicaraguan government. The United States' lack of participation in the full authority of the ICJ directly diminishes the court's ability to hold states accountable for violations of international laws and norms, and diminishes the world's ability to prevent genocide.

National Interest and Political Will

Two main reasons have been given for the United States' failure to prevent genocide: national interest and political will.

Although awash in lofty rhetoric about human rights and democracy, the United States often pursues what it sees as its own best interest. Frequently this amounts to a calculation based on its relations with individual members of the international community: When enemy states commit massacres, the United States responds with condemnation, sanctions, and possibly military intervention. In contrast, when the perpetrator of serious human rights violations is a U.S. client state, the United States remains silent -- or, at most, issues an occasional rhetorical condemnation.

The "political will" narrative suggests that the country's heart is in the right place but that policymakers are prevented by domestic political considerations from taking the necessary action to stop genocide. In their 2008 report on the occasion of the 60th anniversary of the Genocide Convention, "Preventing Genocide: A Blueprint for U.S. Policymakers," Madeleine Albright and William Cohen made this argument forcefully, repeatedly calling for improved leadership and political will.

But the story of America's relationship with genocide is far more than a case of purposeful negligence. The United States has had close ties with numerous genocidal regimes, despite being a signatory to the Genocide Convention.

Selective Outrage and Complicity

Years of massacres around the world demonstrate Washington's selective outrage: condemnation of certain atrocities and silence or complicity toward others.

One of the most famous cases of the United States remaining silent occurred in 1971. On March 25, the regime based in West Pakistan launched "Operation Searchlight," which initiated its genocide against Bengalis in East Pakistan (present day Bangladesh). Acting with the courage to challenge his own government, Arthur Blood, at the time the U.S. general consul in Dhaka, sent what came to be known as the "Blood Telegram." In it, he and others criticized the U.S. government for failing to denounce Pakistan's "genocide" and for choosing "not to intervene, even morally."

This silence in the face of massacre can be explained by geopolitics. At the time, the United States and China were using Pakistan as an intermediary in their attempt to open and improve Sino-American relations. Despite Blood's passionate insistence that genocide was taking place, the Nixon administration refused to use the word "genocide" to describe the atrocities. Doing so would have implied an obligation to intervene under the Genocide Convention and undermined the administration's geopolitical goals.

Halfway around the world and a decade later, the United States not only fell silent, but actively supported a government while it was committing genocide. Following Efrain Rios Montt's military coup in March 1982, the Guatemalan army massacred indigenous Mayan villagers deemed sympathetic towards leftist rebels. The suppression of left-wing activity fit squarely with U.S. goals during the Cold War. When the Commission for Historical Clarification presented its final report, Guatemala: Memory of Silence, in 1999, it found that 83 percent of the victims had been Mayan and concluded that "agents of the state committed acts of genocide against groups of Mayan people."

The Reagan administration had been no passive bystander in this crime. During Rios Montt's recent trial on charges of genocide, award-winning journalist Allan Nairn reminded us that "U.S. military attaches in Guatemala, the CIA people who were on the ground aiding the G2 military intelligence unit, [and] the policy-making officials back in Washington...were direct accessories to and accomplices to the Guatemalan military. They were supplying money, weapons, political support, intelligence." Far from standing silently by, the United States directly supported those committing the atrocities in order to achieve its own Cold War goals.

A mere six years later, the Reagan administration once again gave support to a genocidal regime--this time Saddam Hussein's Iraq. Despite the fact that Washington had facilitated arms transfers to Iran during the Iran-Contra affair, the Reagan administration did not want Iraq to lose in its war with Iran, which raged throughout the 1980s and claimed over a million lives. Despite knowing full well that the Iraqi leader had used chemical weapons to commit genocide against Iraq's Kurdish population, U.S. government officials continued to support Hussein. According to journalist Mike Shuster, in the 1980s the United States "play[ed] a key role in all of [Hussein's] actions, military and political." Hussein, according to Shuster, "was meeting with senior U.S. diplomats. They were looking the other way when he was using chemical weapons and developing other unconventional weapons. He couldn't have helped but to think that the United States was behind him." And so once again, geopolitical considerations led the United States to back a dictator engaged in genocide.

Over two decades later, the Obama administration has similarly maintained relations with genocidal regimes. In 2010, a leaked UN report alleged that Rwanda, under current president Paul Kagame, may have committed a reprisal genocide against ethnic Hutus who had taken refuge in the neighboring DRC. More recently, Rwanda has been accused of having direct control over the Congolese M23 rebel group, which UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Navy Pillay called "among the worst perpetrators of human rights violations in the DRC, or in the world." But Paul Kagame has maintained close relations with the United States ever since the 1994 genocide, and Rwanda remains a strategic ally for the United States in central Africa.

A similar drama may be unfolding in Myanmar, where Muslim Rohingya villagers have been denied their right to citizenship and targeted by Buddhist mobs and sympathetic security forces as part of a campaign to ethnically cleanse Myanmar of its Rohingya population. According to Human Rights Watch, "An ethnic Arakanese campaign of violence and abuses since June 2012 facilitated by and at times involving state security forces and government officials has displaced more than 125,000 Rohingya and Kaman Muslims in western Burma's Arakan State. Tens of thousands of Rohingya still lack adequate humanitarian aid - leading to an unknown number of preventable deaths - in isolated, squalid displacement camps."

The systematic nature of these abuses -- and the involvement of Myanmar officials -- constitutes crimes against humanity as defined by the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. Further, if the intent behind the policy of isolating Rohingya in camps and denying them access to humanitarian aid is their eventual death, Myanmar's crimes could elevate to genocide under Article 2 of the Genocide Convention, which includes "deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part."

Ahamed Jarmal, Secretary General of the Burmese Rohingya Organization, recently warned that "the situation is getting really desperate. Mobs have attacked our villages, driving us from our homes, children have been hacked to death, and hundreds of my people have been killed by members of the majority. Thugs are distributing leaflets threatening to 'wipe us out' and children in schools are being taught that the Rohingya are different." Yet minor democratic reforms and the release of some political prisoners were rewarded with the lifting of sanctions and visits to Myanmar by then Secretary of State Clinton, as well as President Obama. More recently, President Obama welcomed Myanmar president Thein Sein to the United States.

In November 2012, prior to President Obama's visit to Myanmar, U.S. Ambassador to the UN Samantha Power wrote glowingly of the Obama administration's support for human rights in Myanmar and the reforms already underway. Yet Power also tempered the praise, warning that "We are clear-eyed about the challenges that Burma faces. The peril faced by the stateless Rohingya population in Rakhine State is particularly urgent, and we have joined the international community in expressing deep concern about recent violence that has left hundreds dead, displaced over 110,000, and destroyed thousands of homes."

More than a year later, conditions for the Rohingya have worsened. Yet U.S. policy stays the course, a classic exemplification of the foreign policy of selective outrage. Myanmar is committing crimes against humanity, yet is rewarded with the lifting of sanctions and presidential visits. The good treatment is no wonder: resource-rich Myanmar holds economic opportunities for the United States and is strategically located on China's southwestern border.

The United States does not have a policy of disengagement when it comes to the prevention of genocide. Rather, U.S. policy is far worse: it operates on a principle of direct engagement with -- and sometimes support of -- genocidal regimes when Washington's geopolitical goals demand it.

Prevention

The Genocide Convention requires not only that perpetrators of genocide be held to account, but also that countries prevent genocide from occurring in the first place.

In 2007, the ICJ ruled in the case of Bosnia v. Serbia that Serbia failed to fulfill its obligation under the Genocide Convention to prevent genocide. According to the ICJ, "In view of their undeniable influence," the Yugoslav federal authorities should "have made the best efforts within their power to try and prevent the tragic events then taking shape, whose scale, though it could not have been foreseen with certainty, might at least have been surmised." The ICJ ruled that Serbia had the necessary influence over the Bosnian Serbs to at least attempt to use that influence to deter the Bosnian Serbs from committing genocide against Bosnian Muslims.

What about the United States? Did it wield the necessary influence over the Pakistani, Guatemalan, and Iraqi governments to have failed to fulfill its own obligation to prevent genocide? Does the Obama administration hold the necessary influence in Rwanda and Myanmar today?

Vera Saeedpour, the late Kurdish specialist, once lamented that "Until the priorities of the international community are reordered to place human life in a loftier position, I fear that our efforts will be largely relegated to recording atrocities in history books." The universal eradication of genocide and other mass atrocity crimes requires a revolutionary change in philosophy 3/4 one that elevates human life above the national interest.

A good first step would be to redefine protecting human life as a national interest. President Barack Obama intimated as much two years ago when he presented his "Presidential Study Directive on Mass Atrocities." He said at the time, "Preventing mass atrocities and genocide is a core national security interest and a core moral responsibility of the United States. Our security is affected when masses of civilians are slaughtered, refugees flow across borders, and murderers wreak havoc on regional stability and livelihoods. America's reputation suffers, and our ability to bring about change is constrained, when we are perceived as idle in the face of mass atrocities and genocide."

Obama went on to create an "interagency Atrocities Prevention Board" to "coordinate a whole of government approach to preventing mass atrocities and genocide." Human rights groups have generally welcomed this development, but have recommended that the administration publicly state what the comprehensive strategy for preventing atrocities is, improve transparency, consult with civil society groups and Congress, coordinate its efforts internationally, address actual emergencies in the world, and make sure the board has the resources to be effective.

But the problems go much deeper. To have true effect, such a task force would need to recognize when genocide has been -- or is about to be -- perpetrated by countries the United States considers allies. Even further, it would need to take seriously the United States' own complicity in genocide -- and commit to preventing it by transforming U.S. foreign policy.

Nothing can excuse the outrageous failure to prevent genocide. The United States needs to stop selectively condemning countries only when it is in its own supposed interest to do so. It needs to create a uniform standard for condemning human rights violations. And it needs to recognize the jurisdiction of the ICJ, as well as the International Criminal Court. If that means taking responsibility -- and risk -- for being held to account for its own violations of human rights, then all the better.

___________________