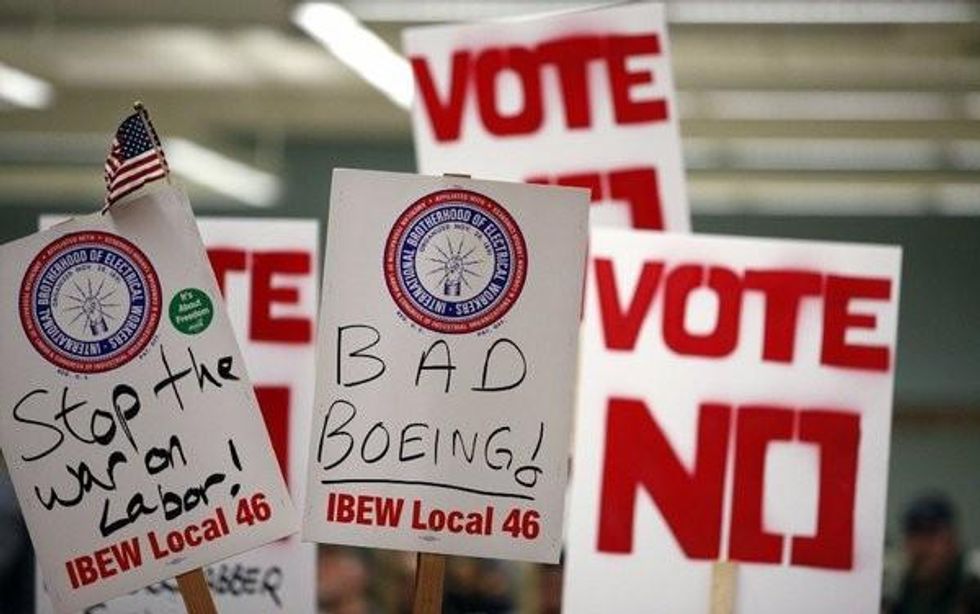

Anyone following last Friday's epochal vote in Washington state on a union contract at Boeing could tell from the workers' comments in various forums that the key issue wasn't whether the contract was good or bad, or even whether Boeing was a good or bad company to work for.

The rank-and-file majority seemed to think that the contract stank. No one cared much for Boeing as an employer, either. The issue was whether Boeing was bluffing about moving a big new airliner construction program out of state if the contract vote failed. Those who thought the firm was bluffing voted against the deal; those who thought its threat was real voted "yes."

"What's really happening is that Boeing, which is as financially healthy as it's been in years, is aggressively steering the fruits of its success to its executives and shareholders and shortchanging the workers who got it there."

"Yes" took it, by a razor-thin majority of 51% to 49%. Supposedly this means that Boeing is committed to building its new 777X airliner in the Seattle area. But you probably won't lose money betting that the firm will find a way to outsource some of the work to non-union locales.

That brings us to the real impact of the contract vote, which is that it continues--even accelerates--the hollowing-out of America's once-thriving middle class.

Boeing executives maintained that major concessions were needed from the machinists' union to guarantee the 777X program for Seattle. They said the intense competition in the aircraft industry and price discounts demanded by customers made the givebacks essential.

But what's really happening is that Boeing, which is as financially healthy as it's been in years, is aggressively steering the fruits of its success to its executives and shareholders and shortchanging the workers who got it there.

Let's start at the bottom, with the contract. Actually, it's an eight-year extension to a pact that doesn't expire until 2016. Under its terms, Boeing will abandon its traditional defined-benefit pension plan, substituting an expanded 401(k). The old plan will be frozen, meaning that accruals to pension benefits from worker longevity and wages will shortly cease. (Pension values that workers have already earned they'll keep, as is required by federal law.)

As is true of all 401(k)-style defined contribution plans, the new system places more of the risk of retirement security on the workers, leaving the company largely risk-free. It will match employee contributions up to a certain level, but there's no guarantee that it won't seek to cut that commitment in the future.

The contract limits general pay increases to 1% every other year through 2023, outside of cost-of-living raises and a quality incentive program that could add up to 6% of pay, but could also yield nothing. And it shifts more of the cost of health insurance to the worker, raising deductibles and the workers' share of premiums. Workers who pay $66 a month for family coverage now will be paying $234 by the end of the contract.

Any way you cut it, the workers are getting squeezed. A Boeing machinist job, once the reliable foundation of a middle-class lifestyle, will be much less of one in the future. It won't be exactly hard time--with average pay about $70,000 "it's still one of the best deals you can get for a blue-collar worker without a college degree," observes Leon Grunberg, a labor relations expert at the University of Puget Sound--but it shrinks the workers' economic horizons considerably, especially for younger workers.

Most significant, Grunberg says, is Boeing's attack on the defined-benefit pension. These have been disappearing all over corporate America, but until now companies with strong unions haven't shared in the trend.

"This is a harbinger of what's going to happen in the unionized sector," Grunberg told me. Boeing thus achieved a double-barreled victory--it shed its pension obligations and made the union less relevant to its workers' lives with one stroke.

So if Boeing is gaining so muich with this deal, where are the gains going? The answer, as is true throughout corporate America, is to shareholders and executives. Under Chairman and Chief Executive James McNerney, who took over in 2005, the company has increased its dividend every year but one, from $1.05 to $2.92 in 2014. That's a total increase of 178%, including a huge bump of 51% this year alone.

At the same time, the company has authorized $17 billion in share buybacks. That's just another way of shoveling money out to shareholders, and surely accounts for a good portion of the company's handsome run-up in share price over the last year, when it has appreciated by more than 80%.

McNerney has done well by doing so good for his shareholders. In 2012, the last year reported by Boeing, he collected $27.5 million in cash, bonus, stock and option awards, and other pay. That was a 20% raise over the previous year, in which he got a roughly 16% raise over 2010. He must be a superman to be so uniquely responsible for the company's success--his 2012 pay was almost as much as that collected by the next three highest-paid members of his executive team combined.

Despite Boeing's insistence that it couldn't survive without concessions from its workers, the real question is whether its executives are sowing the seeds for its long-term decline.

The issue emerged earlier with the fiasco of its mass-outsourcing of components for its vaunted 787 Dreamliner airliner. The firm's determination to have the parts built and assembled all over the country and the world before final assembly in the U.S. made the project billions of dollars over budget and three years late. Only then did the company discover that it had given the important work to inexperienced companies without bothering to impose adequate oversight. That was the admission of then-commercial airline chief Jim Allbaugh in 2011. (A year later, he was out on his rear end.)

Others wonder whether in outsourcing so much engineering work, Boeing isn't helping to educate its own future rivals about how to eat its lunch. "Boeing effectively gave Tier 1 suppliers a large part of its proprietary manual, 'How to Build a Commercial Airplane,' a book that its aeronautical engineers have been writing over the last 50 years or so," writes Dick Nolan, a professor of business administration at the University of Washington.

But the company's real quest is to determine how tightly it can squeeze its own workforce. In that field it's among the trendsetters, though it has a few advantages. At the moment it's one of only two major manufacturers in its industry worldwide, and the only one in the U.S. It takes a hardy politician to resist the lure of a major aircraft plant, and in fact the state of Washington shoveled out a record $8 billion in incentives to Boeing to keep this one. And Boeing has jobs to offer in an economy where they're scarce; why should it care that its workers are ticked off?

That's the landscape of the new world. "Research used to tell us that you want a workforce that's committed and happy," Grunberg says. "But Boeing's been doing very well with a workforce that's unhappy."

Only time will tell us if Boeing's strategy is wrong, and by the time we learn the answer, it may be too late for the middle class.