SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

Jordan Davis was afraid. He wished he was at home with his parents after the first shot - never anticipating that his routine goodbye before a night out with is friends would be his final farewell. The second shot ricocheted off of the red SUV, and eight more would follow from Michael Dunn's gun.

Jordan Davis was afraid. He wished he was at home with his parents after the first shot - never anticipating that his routine goodbye before a night out with is friends would be his final farewell. The second shot ricocheted off of the red SUV, and eight more would follow from Michael Dunn's gun.

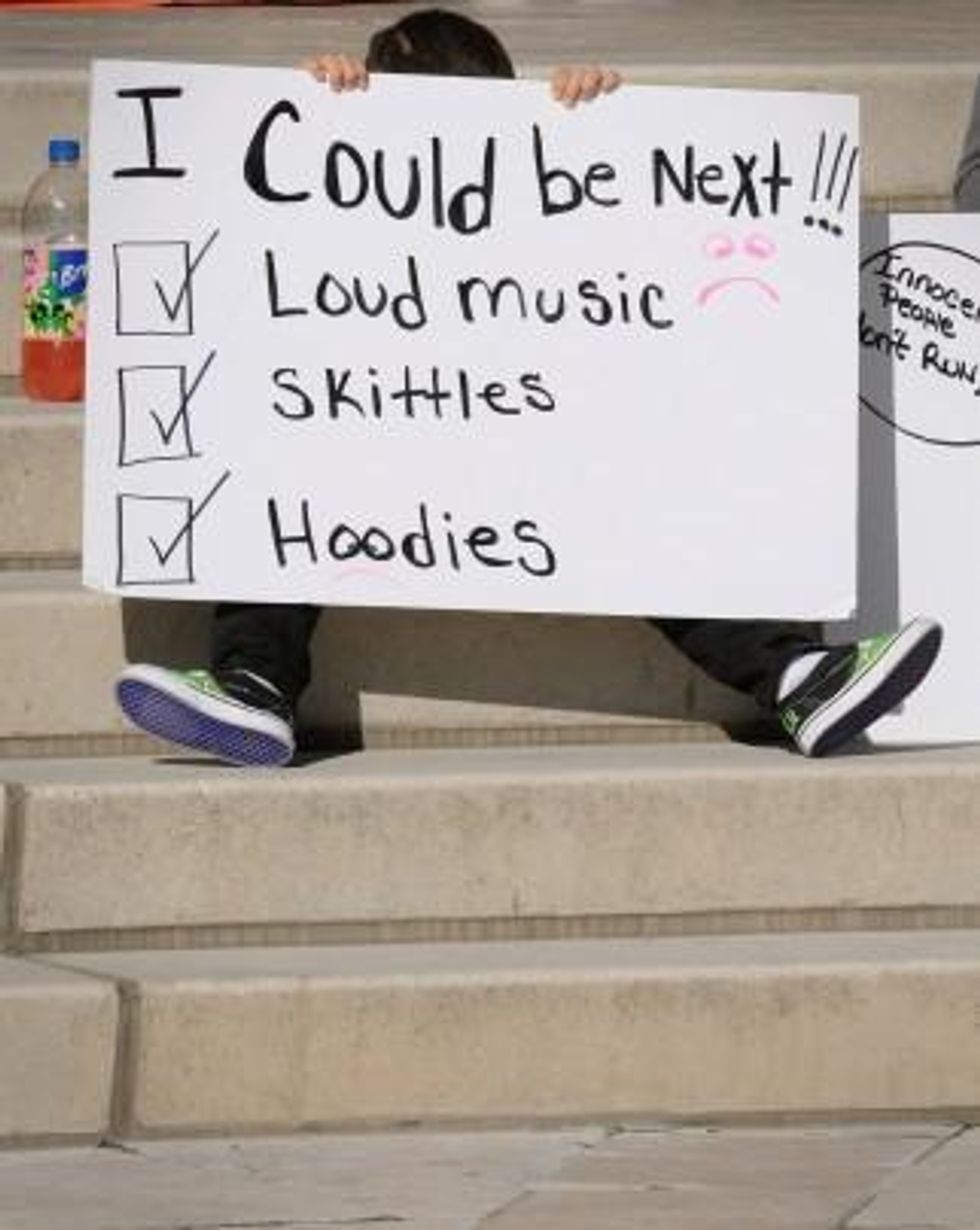

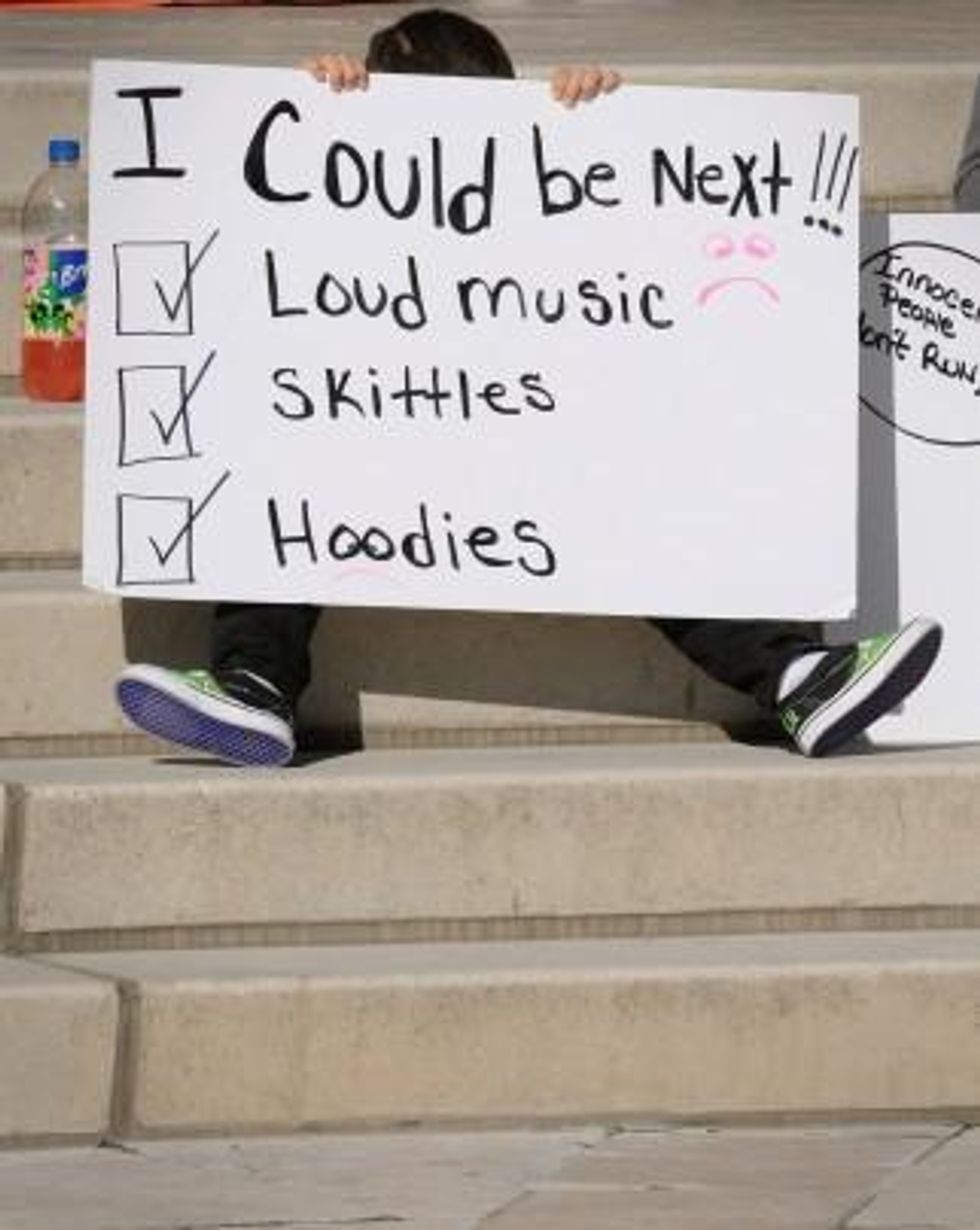

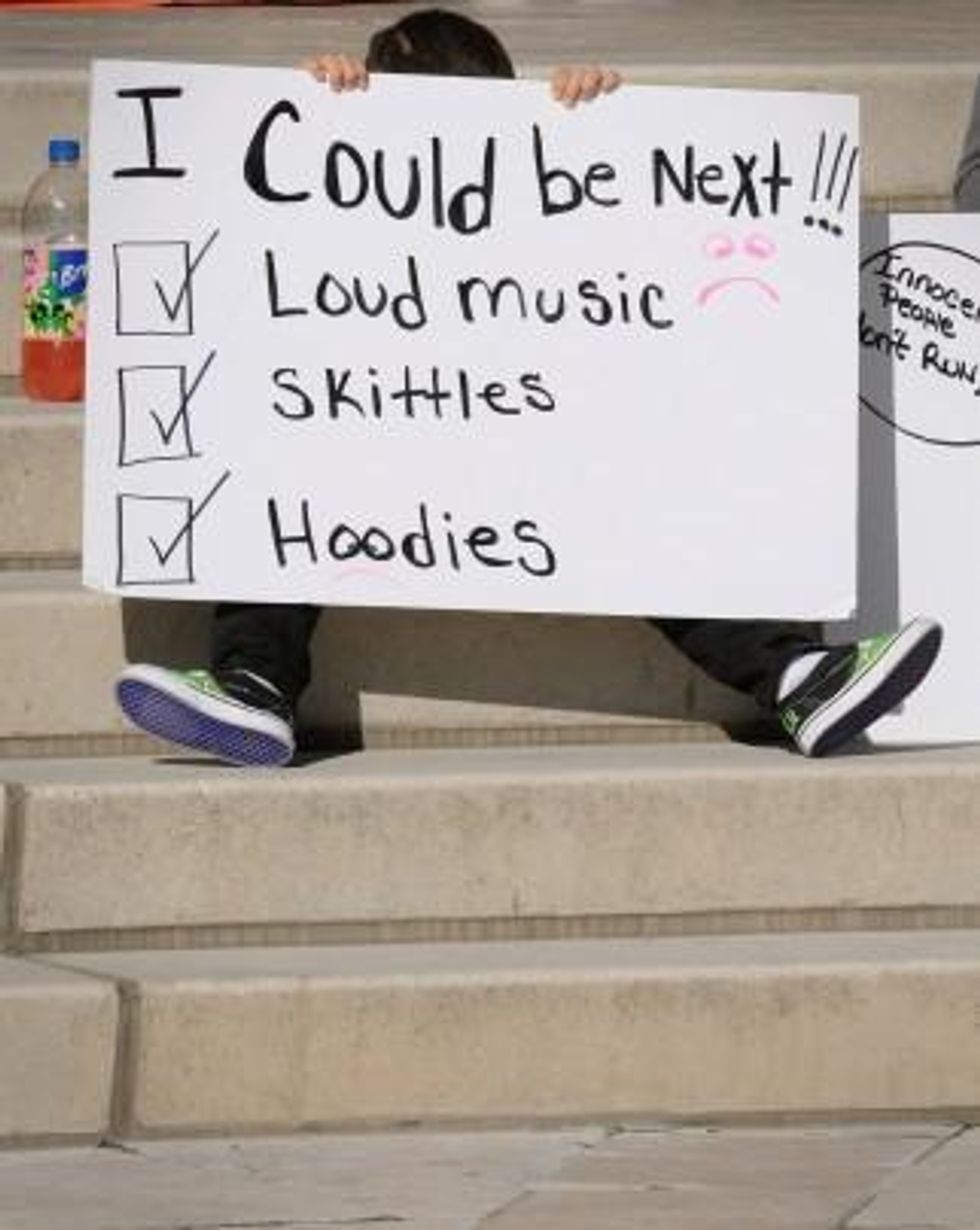

Davis and his three friends were unarmed. However, their Black skin, amplified by the "thug music" coming from their car, was weapon enough for Dunn to unleash a barrage of shots that killed Davis. Dunn fired three shots as the car retreated with Davis' dead body within it. Yet it was his "fear" that determined the jury's verdict on Saturday.

Fear and racism are distinct perspectives, segregated by the line that divides autonomic emotion from ideology. Yet, for Dunn, they were same during his murder trial and on the day he killed Jordan Davis. He imagined a "black man with a shotgun," but instead, killed an unarmed black boy. Dunn's "fear" may have been conjured up or constructed by his defense. But it was inarguably code for racism, which armed him with a defense that has so far saved him from a first-degree murder conviction.

Weaponization of Blackness

Hours before the verdict was reached, Aura Bogado wrote: "The Dunn Trial will determine whether or not an unarmed black child's body is, in and of itself, a deadly weapon." Like Trayvon Martin, another unarmed Florida youth, the court reaffirmed that Blackness - in and of itself - posed an imminent threat.

Michael Dunn "was not convicted for killing a black boy" as the jury could not agree to first-degree murder charges, thereby establishing that Dunn's fear was legitimate.

Again, it was Dunn that fired ten shots at an SUV with four youth. It was Davis, and his three friends, who braced themselves with each consecutive shot, not knowing how many shots would come but fearing that the next one could take their life. It was Dunn who chose not to call the police after hearing the "thug music" coming from the SUV, and proceeded to grab his gun from his car.

It was Davis, alone, whose life was taken that day on November 23rd 2012, yet Dunn's irrational and racist fear of a "black, masculine menace" that steered the trajectory of the trial and determined its verdict.

The Racial Construction of Fear

Jordan Davis could not testify about his fear in court. Dunn's fear trumped Davis's, and he unloaded shot after shot until that possibility was still and motionless. Fear did not push Dunn to run or drive away, avoid engagement, or call the police. Rather, it pulled him in the other direction. His imagination, colored by white privilege and anti-black racism, emboldened him to take justice into his own hands.

Criminal courts, time after time, have cleared white assailants and emboldened the vigilante racist killing illustrated by Dunn, and Martin's killer, George Zimmerman. Beneath the strategic claims of fear is an air of invincibility endorsed by the court, and an institutionalized racism that facilitates the resonance of such absurd defenses that we all, as Americans, are heirs of and have inherited.

The strength of Dunn's defense was directly proportional to the degree of his racist performance in court. Dunn's vilified Davis's Blackness, corroborated it with an indictment of hip hop as "gangster rap," and constructed the anatomy of the stereotypical black "thug" for the jury.

Mitigating the specific intent necessary for first-degree murder required this robust display of racism, and the concomitant presentation of white victimhood that often accompanies it. Yet, the "victim" was alive in court, and the "threat" dead and buried, highlighting the racial juxtaposition that typically characterizes murder trials involving a white assailant and a black victim. Such trials are also real time exercises that highlight the structural racism embedded in every level of the criminal justice system - from police profiling, school-to-prison pipelines, and surely, criminal trials themselves.

Racism within the courts is neither past nor present - it is always. This imminent threat, I fear, will only embolden and arm more Michael Dunns to shoot down and kill more Jordan Davises, until racism is no longer a viable weapon in criminal trials.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Jordan Davis was afraid. He wished he was at home with his parents after the first shot - never anticipating that his routine goodbye before a night out with is friends would be his final farewell. The second shot ricocheted off of the red SUV, and eight more would follow from Michael Dunn's gun.

Davis and his three friends were unarmed. However, their Black skin, amplified by the "thug music" coming from their car, was weapon enough for Dunn to unleash a barrage of shots that killed Davis. Dunn fired three shots as the car retreated with Davis' dead body within it. Yet it was his "fear" that determined the jury's verdict on Saturday.

Fear and racism are distinct perspectives, segregated by the line that divides autonomic emotion from ideology. Yet, for Dunn, they were same during his murder trial and on the day he killed Jordan Davis. He imagined a "black man with a shotgun," but instead, killed an unarmed black boy. Dunn's "fear" may have been conjured up or constructed by his defense. But it was inarguably code for racism, which armed him with a defense that has so far saved him from a first-degree murder conviction.

Weaponization of Blackness

Hours before the verdict was reached, Aura Bogado wrote: "The Dunn Trial will determine whether or not an unarmed black child's body is, in and of itself, a deadly weapon." Like Trayvon Martin, another unarmed Florida youth, the court reaffirmed that Blackness - in and of itself - posed an imminent threat.

Michael Dunn "was not convicted for killing a black boy" as the jury could not agree to first-degree murder charges, thereby establishing that Dunn's fear was legitimate.

Again, it was Dunn that fired ten shots at an SUV with four youth. It was Davis, and his three friends, who braced themselves with each consecutive shot, not knowing how many shots would come but fearing that the next one could take their life. It was Dunn who chose not to call the police after hearing the "thug music" coming from the SUV, and proceeded to grab his gun from his car.

It was Davis, alone, whose life was taken that day on November 23rd 2012, yet Dunn's irrational and racist fear of a "black, masculine menace" that steered the trajectory of the trial and determined its verdict.

The Racial Construction of Fear

Jordan Davis could not testify about his fear in court. Dunn's fear trumped Davis's, and he unloaded shot after shot until that possibility was still and motionless. Fear did not push Dunn to run or drive away, avoid engagement, or call the police. Rather, it pulled him in the other direction. His imagination, colored by white privilege and anti-black racism, emboldened him to take justice into his own hands.

Criminal courts, time after time, have cleared white assailants and emboldened the vigilante racist killing illustrated by Dunn, and Martin's killer, George Zimmerman. Beneath the strategic claims of fear is an air of invincibility endorsed by the court, and an institutionalized racism that facilitates the resonance of such absurd defenses that we all, as Americans, are heirs of and have inherited.

The strength of Dunn's defense was directly proportional to the degree of his racist performance in court. Dunn's vilified Davis's Blackness, corroborated it with an indictment of hip hop as "gangster rap," and constructed the anatomy of the stereotypical black "thug" for the jury.

Mitigating the specific intent necessary for first-degree murder required this robust display of racism, and the concomitant presentation of white victimhood that often accompanies it. Yet, the "victim" was alive in court, and the "threat" dead and buried, highlighting the racial juxtaposition that typically characterizes murder trials involving a white assailant and a black victim. Such trials are also real time exercises that highlight the structural racism embedded in every level of the criminal justice system - from police profiling, school-to-prison pipelines, and surely, criminal trials themselves.

Racism within the courts is neither past nor present - it is always. This imminent threat, I fear, will only embolden and arm more Michael Dunns to shoot down and kill more Jordan Davises, until racism is no longer a viable weapon in criminal trials.

Jordan Davis was afraid. He wished he was at home with his parents after the first shot - never anticipating that his routine goodbye before a night out with is friends would be his final farewell. The second shot ricocheted off of the red SUV, and eight more would follow from Michael Dunn's gun.

Davis and his three friends were unarmed. However, their Black skin, amplified by the "thug music" coming from their car, was weapon enough for Dunn to unleash a barrage of shots that killed Davis. Dunn fired three shots as the car retreated with Davis' dead body within it. Yet it was his "fear" that determined the jury's verdict on Saturday.

Fear and racism are distinct perspectives, segregated by the line that divides autonomic emotion from ideology. Yet, for Dunn, they were same during his murder trial and on the day he killed Jordan Davis. He imagined a "black man with a shotgun," but instead, killed an unarmed black boy. Dunn's "fear" may have been conjured up or constructed by his defense. But it was inarguably code for racism, which armed him with a defense that has so far saved him from a first-degree murder conviction.

Weaponization of Blackness

Hours before the verdict was reached, Aura Bogado wrote: "The Dunn Trial will determine whether or not an unarmed black child's body is, in and of itself, a deadly weapon." Like Trayvon Martin, another unarmed Florida youth, the court reaffirmed that Blackness - in and of itself - posed an imminent threat.

Michael Dunn "was not convicted for killing a black boy" as the jury could not agree to first-degree murder charges, thereby establishing that Dunn's fear was legitimate.

Again, it was Dunn that fired ten shots at an SUV with four youth. It was Davis, and his three friends, who braced themselves with each consecutive shot, not knowing how many shots would come but fearing that the next one could take their life. It was Dunn who chose not to call the police after hearing the "thug music" coming from the SUV, and proceeded to grab his gun from his car.

It was Davis, alone, whose life was taken that day on November 23rd 2012, yet Dunn's irrational and racist fear of a "black, masculine menace" that steered the trajectory of the trial and determined its verdict.

The Racial Construction of Fear

Jordan Davis could not testify about his fear in court. Dunn's fear trumped Davis's, and he unloaded shot after shot until that possibility was still and motionless. Fear did not push Dunn to run or drive away, avoid engagement, or call the police. Rather, it pulled him in the other direction. His imagination, colored by white privilege and anti-black racism, emboldened him to take justice into his own hands.

Criminal courts, time after time, have cleared white assailants and emboldened the vigilante racist killing illustrated by Dunn, and Martin's killer, George Zimmerman. Beneath the strategic claims of fear is an air of invincibility endorsed by the court, and an institutionalized racism that facilitates the resonance of such absurd defenses that we all, as Americans, are heirs of and have inherited.

The strength of Dunn's defense was directly proportional to the degree of his racist performance in court. Dunn's vilified Davis's Blackness, corroborated it with an indictment of hip hop as "gangster rap," and constructed the anatomy of the stereotypical black "thug" for the jury.

Mitigating the specific intent necessary for first-degree murder required this robust display of racism, and the concomitant presentation of white victimhood that often accompanies it. Yet, the "victim" was alive in court, and the "threat" dead and buried, highlighting the racial juxtaposition that typically characterizes murder trials involving a white assailant and a black victim. Such trials are also real time exercises that highlight the structural racism embedded in every level of the criminal justice system - from police profiling, school-to-prison pipelines, and surely, criminal trials themselves.

Racism within the courts is neither past nor present - it is always. This imminent threat, I fear, will only embolden and arm more Michael Dunns to shoot down and kill more Jordan Davises, until racism is no longer a viable weapon in criminal trials.