The most renowned media critics are usually superficial and craven. That's because -- as one of the greatest in the 20th century, George Seldes, put it -- "the most sacred cow of the press is the press itself."

No institutions are more image-conscious than big media outlets. The people running them know the crucial importance of spin, and they'll be damned if they're going to promote media criticism that undermines their own pretenses.

To reach the broad public, critics of the media establishment need amplification from . . . the media establishment. And that rarely happens unless the critique is shallow.

The exceptions can be valuable. The New York Times publishes articles by a "public editor" -- an independent contractor whose "opinions and conclusions are her own" -- and the person now in that role, Margaret Sullivan, provides some cogent scrutiny of the newspaper's coverage.

But on the whole, the media critics boosted by big media -- inward-facing ombudspersons and outward-facing journalists on a media beat -- have been conformists who don't step outside the shadows cast by the institutions paying their salaries. And they're not inclined to question the corporate prerogatives of other media firms; people in glass skyscrapers don't throw weighty stones.

A year ago, the Washington Post, then still under the ownership of the Graham family, abolished the ombudsperson job at the newspaper after four decades of filling the position with a rotating succession of seasoned -- and conformist -- journalists. The change was a new twist in a downward spiral, but it wasn't much of a loss for readers.

The Post's first ombudsman, who took the job in 1970, went on to many years of management roles for the Washington Post Company and then returned to being the ombudsman in the late 1980s. During his second act, he wrote columns denouncing the Newspaper Guild union that was in conflict with the company -- while he praised the firm's management.

In sharp contrast, the best media critics are truly independent. And so, they're rarely seen or heard via large media outlets.

The death of Doug Ireland six months ago brought back vivid memories. Ireland was a first-rate media critic as well as a deft reporter, astute progressive strategist, path-breaking gay activist and incisive political analyst. Last fall, after he died, one moving tribute after another emerged.

Ireland's work as a critic of U.S. news media shined fierce light on realities of propaganda systems in our midst. He was part of a precious continuum of media criticism from the political left over the last century. It's a de facto tradition worth pondering, to grasp its historic vitality -- and relevance in 2014.

A hundred years ago, Upton Sinclair made a pioneering jump that many others were to emulate in later decades. He was a writer who became an activist -- including a media activist -- as he realized that words on pages and volumes of books would not be enough to overcome the brutal greed of the era's robber barons.

As a witness to atrocities against working people and their families, Sinclair launched a nonstop battle against the press lords and their most powerful wire service, the Associated Press. Sinclair's 1919 book "The Brass Check" -- self-published and widely read -- was a manifesto against the entire capitalist media system of the day. If the prisoners of starvation and exploitation were to arise, they needed to overcome the weaponry of lies, distortions and omissions.

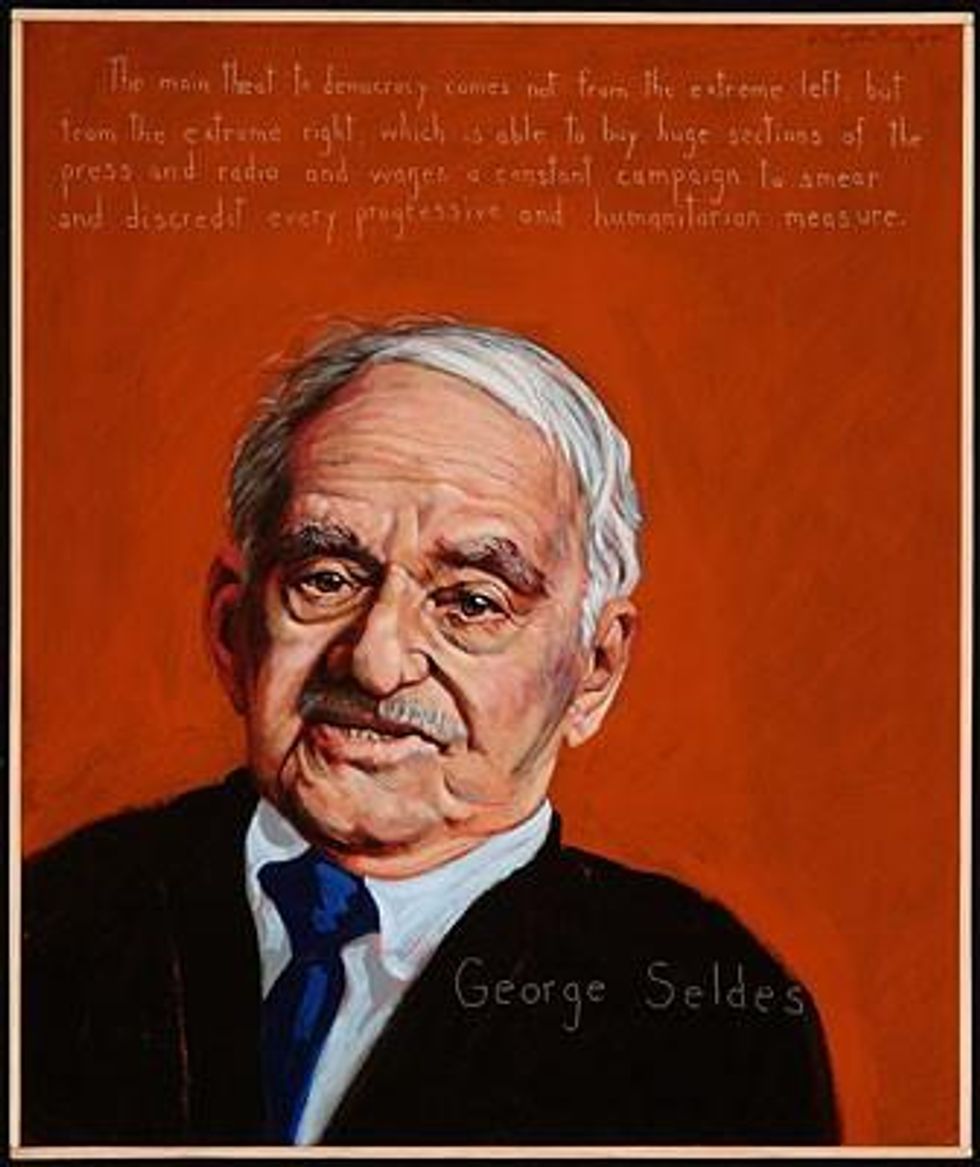

Into the footsteps of Upton Sinclair walked someone who came to media activism not as a novelist but as a journalist. The young reporter George Seldes had covered World War I for the Chicago Tribune and later became the paper's Berlin bureau chief. Beginning in 1921, Seldes covered the nascent Soviet Union for two years before his stories about suppression of non-Bolshevik revolutionaries got him kicked out of the country.

Seldes went on to Italy, but after two years made a harrowing escape -- in imminent danger because of his tough reporting on the fascist dictator Benito Mussolini, who detested independent journalism as much as Vladimir Lenin did.

After clashing with repression overseas, Seldes also chafed at capitalist restrictions that tilted the content of the Tribune to suit its wealthy owner, Col. Robert McCormick. By the 1930s, Seldes was out on his own, writing books like "Lords of the Press," "Facts and Fascism," "Can These Things Be!" and "Never Tire of Protesting." And in 1940 he founded the first regularly published magazine of media criticism.

For a full decade, Seldes' weekly In Fact, printed in newsletter format, blazed trails that turned up the heat on corrupt practices of the U.S. press. Directly challenging the power of rich owners and advertisers, Seldes denounced the media oligarchy as it oversaw coverage that aided fascist momentum in Europe, avaricious factory owners at home, war profiteering, the cigarette industry and other nefarious enterprises.

Relentless and principled, George Seldes and his wife Helen -- from their kitchen table -- built In Fact to a circulation of 175,000 copies. But the advent of McCarthyism, assisted by J. Edgar Hoover's FBI, brought a campaign of harassment and intimidation against subscribers that forced closure of the publication in 1950.

A torch passed to another stubbornly independent journalist, I.F. Stone. While not explicitly engaged in media criticism, I.F. Stone's Weekly, founded in 1953, largely picked up where In Fact left off.

Stone's blunt assessments informed his work. "Every government is run by liars, and nothing they say should be believed," he said. Such skepticism pursued truth -- and the democratic goal of the truly informed consent of the governed. Stone kept busy debunking key deceptions that major media outlets were propagating.

Like so many others, I came to see huge discrepancies between the realities I observed on the ground and the coverage that existed -- or didn't exist -- in mainline corporate news media. My own path led me to become a media critic during the 1980s, after more than a decade of involvement in journalism mixed with activism.

Later, I learned about the passionate work of media criticism by Upton Sinclair, George Seldes and I.F. Stone. I grew to identify with their struggles as writers drawn into fighting the corporate media of their eras.

I was fortunate enough to meet George Seldes. On a warm spring day in 1988, I drove through New England countryside with Martin A. Lee, then editor of the magazine Extra!, published by the media watchdog group Fairness & Accuracy In Reporting (FAIR), which remains today's vibrant successor to In Fact. We were headed to visit Seldes, then 97 years old and living by himself in a house in a small Vermont town.

For six hours, Seldes graciously hosted us while sharing vivid recollections of his journalistic career. He had remarkably sharp memories of firsthand reporting on pivotal world events as distant as the close of the First World War. On a table in one room was a huge pair of scissors atop a pile of clippings; he was still cutting articles out of newspapers. "There are too many to file," he said. "I can hardly keep up with them."

As Martin and I later wrote (in our book "Unreliable Sources"), "Seldes remained an American individualist in the best sense, combining an unpretentious, fiercely independent, intellectual ethic with an unwavering commitment to social justice. For us he was a living inspiration, someone who had supreme confidence in the power of ideas and the capacity of people to see through the hypocrisy of politicians and media pundits. Seldes never stopped believing that the essence of a democratic society is an enlightened, well-informed citizenry."

Such a tenacious belief is what makes media criticism -- and truly independent journalism -- vital to the future of our world.