David Horowitz, founder of an organization called the "Freedom Center," argued that blacks should not be paid reparations for the enslavement of their ancestors. Among his reasons are that:

- There Is No Single Group Clearly Responsible For The Crime Of Slavery

- Most Americans Have No Connection (Direct Or Indirect) To Slavery

- Reparations To African Americans Have Already Been Paid

But slavery, in its various forms of physical and mental torment, has been a part of U.S. history from the beginnings of our country to the present day. There are numerous modern-day corporations who profited immensely - themselves or their predecessors - from slave labor. Only token amounts have been paid back, along with a few scattered apologies.

Four eras of abuse can clearly be identified.

First Era: Before Emancipation

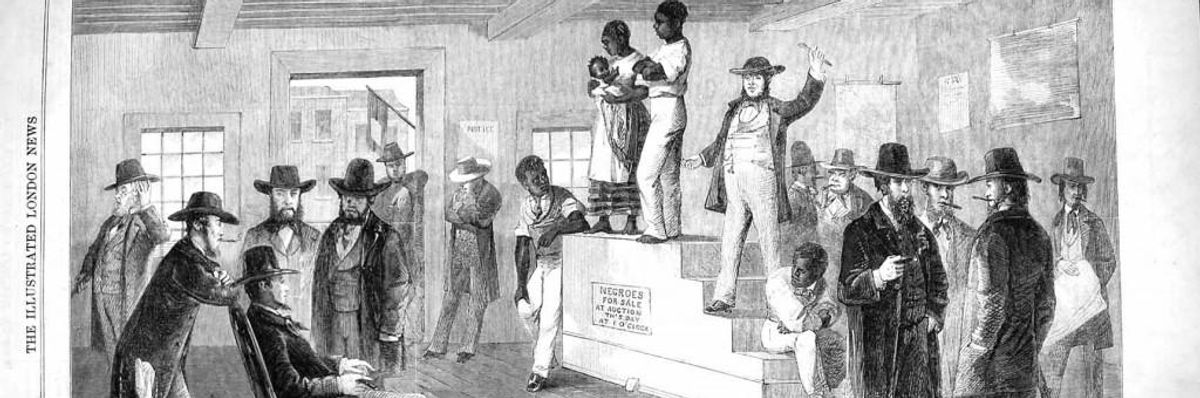

Prior to the Civil War, King Cotton was the rallying cry for the South. With cotton accounting for 60 percent of all U.S. exports, and 75 percent of all the cotton purchased by Great Britain, slaves were needed more than ever. African-Americans in tens of thousands were herded to the deep south, chained neck to neck as they became the hapless tools of industry.

By 1840 there were more millionaires along the Mississippi River than throughout the rest of the nation. Cotton was more valuable than all other U.S. commodities combined. In this "great laboratory of American capitalism" slaves were the most valuable property, and that meant big business for the slave traders, even in the North, as the Fugitive Slave Act legitimatized capture and transport to the South.

Cotton drove the textile industry in the northern states. In 1860, New England had over half of the manufacturing operations, and consumed two-thirds of all the cotton used in U.S. mills. Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts called it "a conspiracy of the lords of the loom and the lords of the lash."

Before the start of the Civil War, the mayor of New York City sought independence from the Union in order to continue its lucrative trading with the South.

Other industries flourished as well, through the predecessors of companies that still exist and thrive today. The Norfolk Southern Railroad leased slaves for one-year terms of hard labor. The parent company of USA Today had links to the slave trade. Insurance companies such as Aetna issued policies protecting slaves as property. Many Wall Street firms, who held slave auctions outside their doors, had their beginnings in the cotton trade. Lehman Brothers, which began investing in 1850, founded the New York Cotton Exchange in 1870. The predecessors of JP Morgan/Chase got their start with loans to slave owners, at times with enslaved Africans as collateral. In 2005 JP Morgan apologized for its predecessors' slave trading activities in Louisiana, and Bank of America and Wachovia also apologized for their early involvement with slave trading.

Second Era: Slavery by Another Name

Slavery was abolished after the Civil War, but in name only. The great hope of Reconstruction lasted just ten years. Now, as Douglas Blackmon documents, a new version of slavery had begun, with arrests for petty 'offenses' such as talking too loud or looking at a white woman. A man committing an actual offense such as stealing a pig could be sentenced to five years of hard labor. These were the "Pig Laws." For many blacks, incarceration meant death, as convict leasing programs allowed companies to work prisoners until they could no longer stand on their feet.

The predecessors of U.S. Steel were complicit in this second era of slavery. One of the tens of thousands of victims was 22-year-old Green Cottenham, arrested in Alabama in March, 1908 for "vagrancy." That means he couldn't prove, at the moment of his arrest, that he was employed. It was a tactic used by local sheriffs and judges to put black men in jail. Ironically, Green's arrest was on the anniversary of the 15th Amendment, which gave blacks the right to vote in 1870.

Cottenham was found guilty and sentenced to thirty days of hard labor. When he was unable to pay court and jailhouse fees, his sentence was extended to a full year, and he was sold to Tennessee Coal, a subsidiary of US Steel. The company forced him to live and work in a mineshaft deep in the black earth, where he worked every day from 3 AM to 8 PM digging and loading tons of coal. If he slowed down he was whipped. He drank the water he was standing in. He was surrounded by caverns filled with poison gas and walls that often collapsed, crushing or suffocating miners. At night he was chained to a wooden barracks. Crazed men were always nearby, filthy and sweaty, some homicidal, some sexual predators. A boy from the Alabama countryside had been deposited in the middle of hell.

Third Era: World War 2 Slave Labor

Slave labor in the Nazi years generated massive profits for many of our most prominent corporations, starting with Ford and General Motors. Henry Ford, who had published "The International Jew: The World's Foremost Problem," was a dear friend of Nazi Germany. His company used prison labor to produce a third of the military trucks for the German army. Ford's Dearborn, MI factory was called an "arsenal of Nazism." In Germany, Ford's worker-inmates were said to have labored for twelve hours a day with six ounces of bread for breakfast and a dinner of turnips and potatoes.

General Motors worked with the German company that built Auschwitz. General Electric partnered with a German company that used slave labor, and invested in the builder of gas chambers. Kodak used prison labor for the manufacture of German arms. Nestle admitted acquiring a company that used forced labor during the war.

Finally, IBM was responsible for the punch card machines that allowed the Nazis to tabulate train shipments to the death camps.

Fourth Era: The Present Day

The 13th Amendment bans slavery "except as punishment for crime." The 14th Amendment bans debt servitude. But each inmate in a modern-day private prison, according to Chris Hedges, "can generate corporate revenues of $30,000 to $40,000 a year." Prisoners accused of minor drug crimes have replaced the vagrants. And private probation companies are keeping them in debt. The system seems little different from the corrupt local governments in the deep South a century ago.

The Corrections Corporation of America and G4S are two of the prison privatizers who sell inmate labor to corporations like Chevron, Bank of America, AT&T, and IBM. Nearly a million prisoners work in factories and call centers for as little as 93 cents an hour.

More corporate profits come from the probation business, which, in direct opposition to the 14th Amendment, keeps people in prison for being too poor to pay their court costs and probation fees. It's called 'peonage,' or debt slavery.

Examples are more than disturbing. In Louisiana, Gregory White, a homeless man, was arrested for stealing $39 worth of food and ended up spending 198 days in jail because he was unable to pay his fines. In Ohio, Howard Webb, who makes $7 an hour as a dishwasher, accumulated almost $3,000 in court costs and probation fees. In Georgia, Thomas Barrett stole a can of beer from a convenience store, was fined $200, and before long owed his probation company $1000, more than a month's pay.

Reparations? One of the arguments against it is that the sheer number of African Americans - 42 million - makes the whole concept unfeasible.

But a financial transaction tax is feasible. It will come to us from the Wall Street firms that used to hold slave auctions outside their doors.