Having read his posthumously published novel, I'm sorry I never knew Michael Hastings. That said, I'm not sure I would have wanted to hang out with him. Hastings's leisure-time pursuits, including the one that appears to have caused his untimely death last year, were a little reckless for my taste.

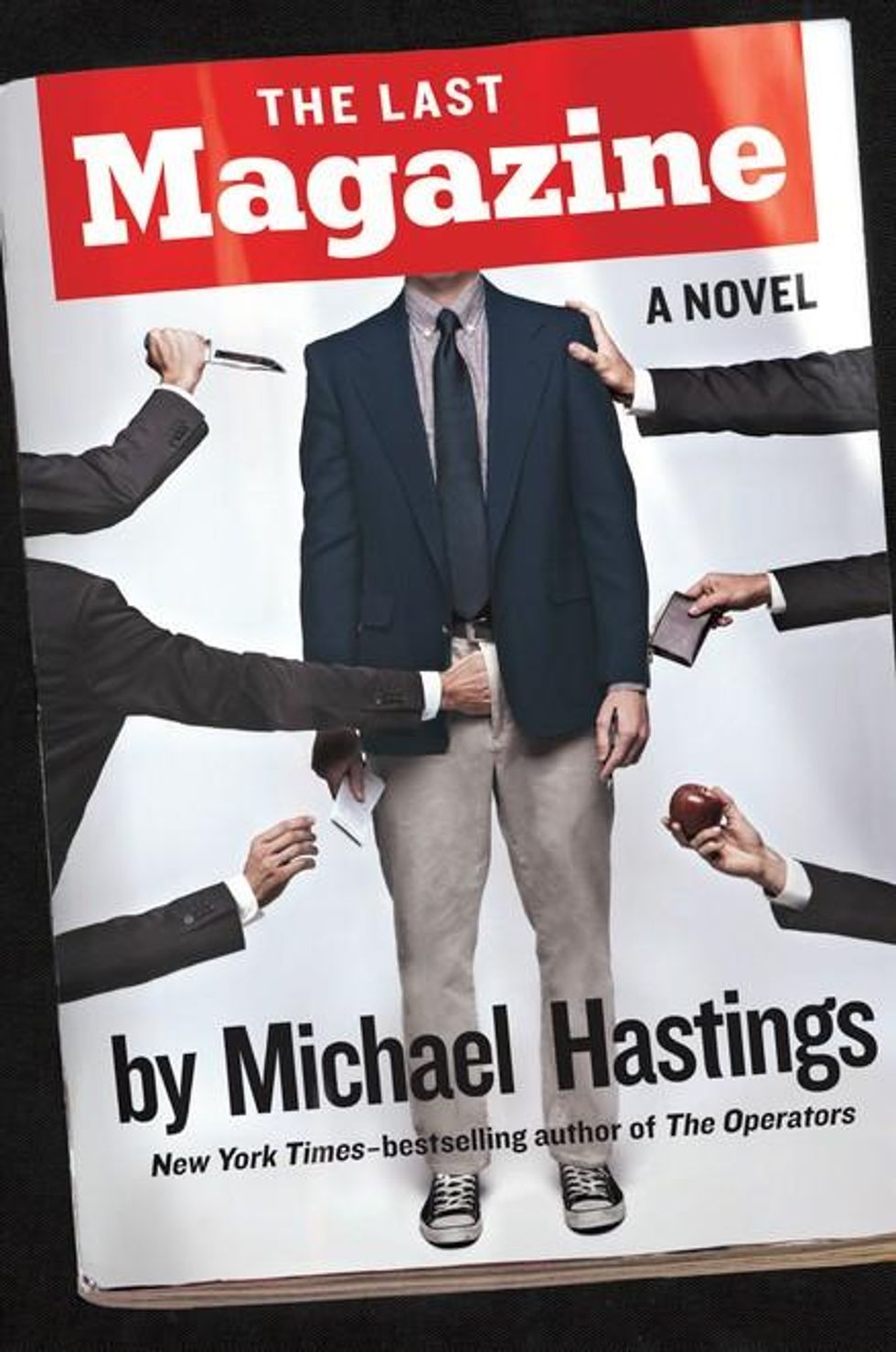

Nevertheless, anyone interested in the politics of journalism -- the politics that led a cavalcade of mainstream journalists and liberal "intellectuals" to support George W. Bush's mad invasion of Iraq -- should read The Last Magazine, which was discovered by Hastings's widow after he crashed his car and died, in Los Angeles, on June 18 of last year. I can't stop being angry about the Iraq catastrophe, no matter how much I try to ignore it. It seems to follow me, though I've never set foot in the country and didn't witness any of the ugliness and gore that informed this outraged, satirical, and pornographic express-train of a book.

On June 9, I was in a beautiful, very peaceful part of rural Vermont when I casually picked up the Sunday Boston Globe. The front page was quiet enough, but the Associated Press dispatch on page two made me wince -- fifty-two people killed in car-bomb attacks in Baghdad and dozens of students taken hostage at Anbar University. Earlier in the day, the city of Mosul, as of this writing in the hands of Sunni rebels, had been the scene of fighting that killed twenty-one police officers and thirty-eight antigovernment militants.

Much of this unrelenting violence is the result of Sunni fury at the repressive Shiite government of Nouri al-Maliki. But the match was lit by Bush and his neoconservative advisers, as well as by their "humanitarian" handmaidens in the media and academia, whose fantasy about a democratic, subservient Iraq continues to pile corpse upon corpse.

Hastings covered post-invasion Iraq for Newsweek beginning in 2005, and something must have torn inside him when his fiancee, Andrea Parhamovich, was ambushed and killed in Baghdad in 2007. Tellingly, Parhamovich was working for the National Democratic Institute, one of those U.S. government-funded do-good front groups that Congress so loves to throw money at while the bloody lessons of bad American foreign policy go unacknowledged. Hastings's most important legacy, I hope, will be his novel's savage characterization of just the sort of people who encouraged his fiancee to risk her life in the service of liberal American "ideals."

In The Last Magazine, Hastings presents himself in the form of two characters, a twenty-something intern-on-the-make actually named Michael M. Hastings, and a crazed, ambitious war correspondent named A. E. Peoria. They both work for a weekly newsmagazine that is obviously the old Newsweek in its waning years of glory. The fictional Michael Hastings is a teetotaler and risk averse -- his battleground is the office politics of who's up and who's down, who can help his career and who can't. Peoria is unable to control either his sex-and-pornography addiction or his huge consumption of drugs and alcohol, but he takes chances on real battlefields and is a miserable failure when it comes to ingratiating himself with the powers back at New York headquarters.

The plot builds around the march to war and its immediate aftermath in 2002-2003, and this first third of the novel is its strongest section. As Bush launches his fraudulent propaganda campaign against Saddam Hussein and his "weapons of mass destruction," we read in amazement as high-profile volunteers from the media fall into line behind the great crusade. If there's a question about where the author Hastings's sympathies lie, they disappear in five pages of contemporaneous quotes from real-life writers and politicians interspersed with fictional quotes from the novel's barely fictional characters. All of them essentially promote the president's case for preemptive attack, beginning with Dick Cheney and ending with a series of fatuous statements from what Hastings calls "Very Important Thinkers from Very Important and Well-Funded Think Tanks."

I could quibble about some omissions -- most notably, David Remnick, editor of The New Yorker, and the Canadian academic and ex-politician Michael Ignatieff -- but Hastings's selection of idiot utterances about Iraq is nearly flawless. Here's Fareed Zakaria in the real Newsweek: "I believe that the Bush administration is right: this war will look better when it's over. . . . Weapons of mass destruction will be found." Then the New York Times's Thomas Friedman: "This is really bold. . . . Mr. Bush's audacious shake of the dice appeals to me." And George Packer in The New York Times Magazine: "These liberal hawks could give a voice to [Bush's] war aims. . . . They could make the case for war to suspicious Europeans and to wavering fellow Americans."

Because the novel's pro-Bush, liberal journalist characters are thinly disguised versions of living, still influential people, one wonders what they might do to undermine Hastings's story.

But the message I take from The Last Magazine goes beyond the interminable bloodshed in Iraq. Zakaria and Packer, who swallowed and regurgitated the Bush lies, are considered great successes. Michael Hastings . . . well, Michael Hastings is dead.

This column originally ran in the Providence Journal on June 19, 2014.