Today, the nation confronts an unacceptable poverty rate of 15 percent. Of course, the conditions that people in poverty contend with--such as overcrowded and inadequate housing, not enough food, lack of opportunities for work, homelessness--these are not new. So as we approach the 50th anniversary of President Lyndon Johnson's signing of the Economic Opportunity Act on August 20, 1964 --the centerpiece of the War on Poverty--it's a good time to reflect not only on Johnson's policies but also the many earlier efforts by activists to reduce poverty in our nation.

The Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness (ICPH) in New York City has published a book (which I co-authored with ICPH president Ralph da Costa Nunez), and launched a companion website, PovertyHistory.org, to tell the history of poverty and homelessness in New York City. These resources demonstrate what has been accomplished in the century-long struggle against poverty and also the work that remains.

To a degree, anti-poverty strategies focus on either assisting individuals or lifting communities. Johnson's War on Poverty, for example, took a decidedly community-centered approach to confronting policy. While some of its greatest successes were policies targeting individuals--like Medicare and Medicaid and SNAP--at the core of the Economic Opportunity Act was the Community Action Program, an effort to provide greater individual opportunity by reviving entire communities.

Here are a few snapshots of other poverty warriors from our past.

The Progressives

Community played a central role for this generation of reformers that came of age between 1890 and 1920. They viewed neighborhoods with high concentrations of poverty, substandard housing, and contagious disease as both a cause and effect of continuing destitution among families in poverty. For this group, later called progressives, the solution lay in strengthening both neighborhood institutions and state interventions.

In the Progressive Era, settlement houses embodied the idea of community-based poverty relief. First established in London in the 1880s, settlements proliferated in U.S. cities over the end of the 19th century and into the first decade of the 20th century. At places such as Hull House in Chicago, and Henry Street Settlement or Greenwich House in New York, young men and women from the middle class came to live, assist, and learn about poor communities. A focus on community infused everything that these settlement workers did. Some of the work was cultural such as providing concerts, lectures, and art exhibits for the neighborhood. But much of the work was about providing direct assistance to poor and working class families, including: medical care, day care, kindergarten, and after-school programs so parents could find work. The reformers also sponsored neighborhood clubs and organizations to help residents focus attention on the problems confronting their communities.

Settlements also became centers of reform. Workers collected extensive data on their communities and their expertise was central in efforts to end child labor, improve housing conditions, and provide state support for widowed or deserted mothers. In calling for these reforms, settlement workers tried to rally their neighbors to get involved, consistent with their missions as community-based organizations.

The New Dealers

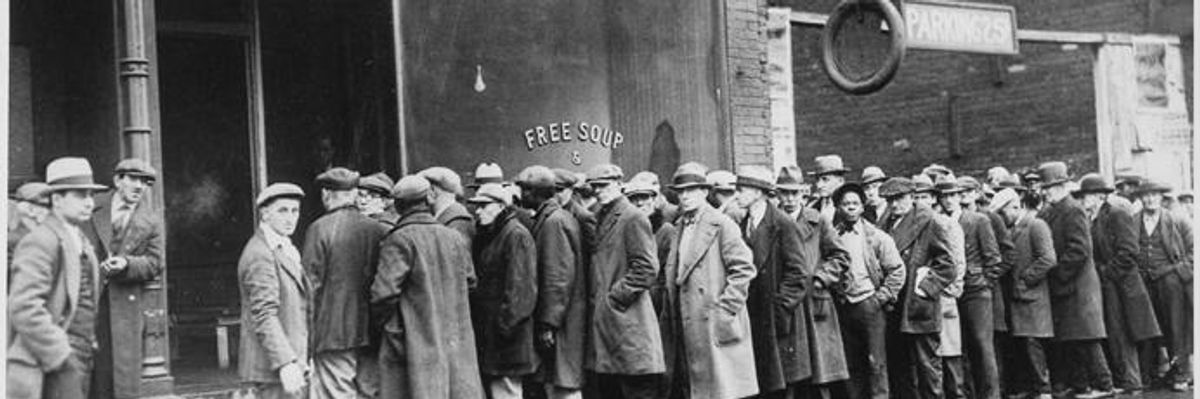

The New Dealers of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt's administration--many of whom had participated in the Progressive Movement--confronted a crisis of unprecedented widespread unemployment and poverty, the Great Depression. Their focus was on relief to those in need, a return to economic growth, and reforms that would prevent poverty in the future. The Roosevelt administration passed wide-reaching legislation to stabilize the economy, ensure protections for workers including the right to organize, and facilitate homeownership. These programs laid the foundation for an expanded middle class after World War II.

At the same time, the New Deal needed to create specific mechanisms to assist families and individuals confronting poverty. Programs such as the Federal Emergency Relief Administration and the Works Progress Administration provided temporary assistance to unemployed people during the Depression. The Social Security Act of 1935 provided a more permanent response to economic vicissitudes and remains one of our greatest pieces of legislation for fighting poverty through today. It offered new federal assistance to the elderly, and created the system of Old Age Insurance that we now call Social Security, which has led to a marked decrease in poverty among the elderly. It also provided federal support for unemployment insurance to prevent hardship in future economic downturns. The Act also contained Aid to Dependent Children (later Aid to Families with Dependent Children, or AFDC)--a program that provided assistance to widowed and deserted mothers. The bill included no general assistance for poor individuals, but Aid to Dependent Children--while never generous and subject to the limitations of each state--would help countless families.

The Fight Today

Today, our poverty programs are a mix of both individually-focused policies and community-based approaches. There are more than 46 million SNAP recipients, and the program kept nearly 5 million people out of poverty last year; in 2012, 26.2 million tax filers received the EITC, and it kept 6.5 million people out of poverty; and a flawed TANF provides assistance to more than 1.5 million families a month. At the same time, many community action agencies and settlement houses continue to provide focused assistance to their local neighborhoods. Programs funded through the Community Development Block Grant, and efforts like the Obama administration's Promise Neighborhoods, are also attempts to strengthen communities in ways that alleviate poverty.

Yet, as Elizabeth Kneebone of Brookings has recently reported, poverty became more concentrated over the 2000s. The solution must be more coordinated individual and community-based antipoverty programs that provide assistance and also the resources--jobs that pay good wages, housing, transportation, access to education, social services, to name a few--that would resuscitate floundering urban neighborhoods and suburban towns.

Our poverty warriors have made great strides in the fight against poverty over the last century. Today, through both individual and community-based tactics, it's time for our next great advance.