Feeding the Roots, Building Democracy: On Painting Peter Kellman

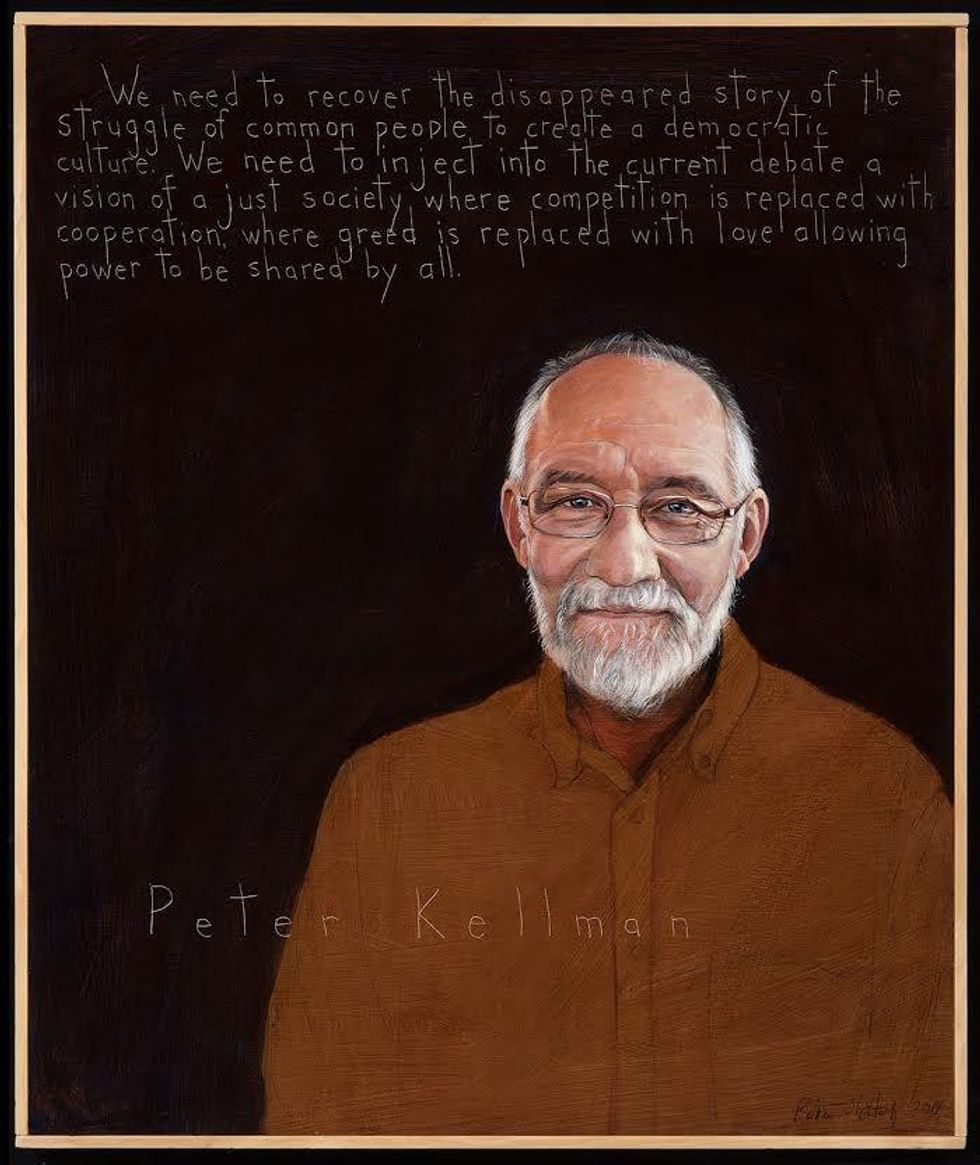

Editor's note: The artist's essay that follows accompanies the 'online unveiling'--exclusive to Common Dreams--of Shetterly's latest painting in his "Americans Who Tell the Truth" portrait series, presenting citizens throughout U.S. history who have courageously engaged in the social, environmental, or economic issues of their time. This painting of union organizer and food community builder Peter Kellman is his latest portrait of those who dedicated their lives to equality, freedom and justice. Posters of this portrait and others are now available at the artist's website.

Often one portrait subject in the Americans Who Tell the Truth project leads to another. Terry Tempest Williams suggested Edward Abbey. Howard Zinn said if he were making the paintings his first portrait would be Fanny Lou Hamer. And Richard Grossman told me about Peter Kellman, his collaborator in forming the 'Program on Corporations, Law and Democracy.' This program had been established to expose how corporations in the United States had used (and continue to use) their powerful financial influence to make that influence legal. The results of that legal influence include not only their much talked about "personhood" but also their legal power in relation to controlling labor rights and unions, pollution restrictions, executive compensation, tax policy, corporate welfare, media, and corporate responsibility. Often the issue of corporate responsibility is described as corporations legally internalizing profit and externalizing cost, or, as privatizing profit and socializing cost, i.e., a power company that make large profits selling energy, but saddles the community with environmental and health costs caused by their mining and production. And, when the special interests of corporations write the law, democracy disappears. The people never know till after the fact how laws have been structured to favor corporate power and profit, and the corporate media rarely reports on how the political system has been gamed.

One of the best little books on this subject turns out to be written by that labor leader and labor historian from Maine, Peter Kellman. It's called Building Unions: Past, Present and Future. Kellman was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1946 and was introduced to labor politics being pushed by his mother in his baby carriage on a picket line. Family conversation was about progressive politics, the struggles of labor, and how to create a just, democratic society. In his late teens he spent three months learning organic agriculture and socialist politics from Helen and Scott Nearing at their farm in Maine, then he went to south in 1965 to help with logistical support for the March on Selma led by Martin Luther King, Jr., and John Lewis. He stayed in Alabama to help build a free (integrated) library. He worked with the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) for a while, then helped organize protests against the Vietnam War and encouraged Draft resistance.

Back in Maine, Kellman began factory work and labor organizing. He was elected president of of Shoe Workers Local 82 fighting for workplace safety, fair wages and regular hours. He was also a major organizer in the Clamshell Alliance, the organization opposing the Seabrook, New Hampshire Nuclear Power Plant. Once he was arrested for refusing to take down anti-nuclear information from the union bulletin board at the shoe company. In a show of solidarity his fellow workers showed up a few days later wearing anti-nuclear buttons. The company caved, brought Kellman and two other workers who had been arrested back to work, paid them for their time off, and asked the county to drop the trespass charges against them. It was a clear victory for workplace democracy.

Perhaps his highest profile work was as an organizer and strategist for the paper workers' strike in Jay, Maine in 1987-88. This prolonged struggle was eventually lost by the workers who felt sold out by their own union leadership. But one thing Kellman learned from that struggle and from all of the other political movements he has been part of was the importance of culture to sustain the movement. Around Civil Rights, Peace, women's, anti-nuclear, gender, and pro-labor movements formed strong "counter-cultures"--music, story, poetry, values, spiritual practice, work ethic, community. But he makes the point that the Peace movement in this country has not succeeded because we have never really built a culture of peace.

Today Kellman is working on building a theory and practice of what he calls the "culture of agriculture." He thinks great attention must be paid to building a culture of local and organic agriculture so that this movement will build community and have deep identity. About his own farming now, he says his effort is not to be self-sufficient. He and his wife Rebekah want to grow much of their own food, but they want to be part of an interdependent agricultural community. Only this way will the movement grow and survive.

Peter Kellman says: "We need to recover the disappeared story of the struggle of common people to create a democratic culture. We need to inject into the current debate a vision of a just society where competition is replaced with cooperation, where greed is replaced with love allowing power to be shared by all."

One of the best ways to do this is to build cultures and communities around local agriculture, people feeding themselves and each other healthy food and caring for the health of the earth.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Editor's note: The artist's essay that follows accompanies the 'online unveiling'--exclusive to Common Dreams--of Shetterly's latest painting in his "Americans Who Tell the Truth" portrait series, presenting citizens throughout U.S. history who have courageously engaged in the social, environmental, or economic issues of their time. This painting of union organizer and food community builder Peter Kellman is his latest portrait of those who dedicated their lives to equality, freedom and justice. Posters of this portrait and others are now available at the artist's website.

Often one portrait subject in the Americans Who Tell the Truth project leads to another. Terry Tempest Williams suggested Edward Abbey. Howard Zinn said if he were making the paintings his first portrait would be Fanny Lou Hamer. And Richard Grossman told me about Peter Kellman, his collaborator in forming the 'Program on Corporations, Law and Democracy.' This program had been established to expose how corporations in the United States had used (and continue to use) their powerful financial influence to make that influence legal. The results of that legal influence include not only their much talked about "personhood" but also their legal power in relation to controlling labor rights and unions, pollution restrictions, executive compensation, tax policy, corporate welfare, media, and corporate responsibility. Often the issue of corporate responsibility is described as corporations legally internalizing profit and externalizing cost, or, as privatizing profit and socializing cost, i.e., a power company that make large profits selling energy, but saddles the community with environmental and health costs caused by their mining and production. And, when the special interests of corporations write the law, democracy disappears. The people never know till after the fact how laws have been structured to favor corporate power and profit, and the corporate media rarely reports on how the political system has been gamed.

One of the best little books on this subject turns out to be written by that labor leader and labor historian from Maine, Peter Kellman. It's called Building Unions: Past, Present and Future. Kellman was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1946 and was introduced to labor politics being pushed by his mother in his baby carriage on a picket line. Family conversation was about progressive politics, the struggles of labor, and how to create a just, democratic society. In his late teens he spent three months learning organic agriculture and socialist politics from Helen and Scott Nearing at their farm in Maine, then he went to south in 1965 to help with logistical support for the March on Selma led by Martin Luther King, Jr., and John Lewis. He stayed in Alabama to help build a free (integrated) library. He worked with the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) for a while, then helped organize protests against the Vietnam War and encouraged Draft resistance.

Back in Maine, Kellman began factory work and labor organizing. He was elected president of of Shoe Workers Local 82 fighting for workplace safety, fair wages and regular hours. He was also a major organizer in the Clamshell Alliance, the organization opposing the Seabrook, New Hampshire Nuclear Power Plant. Once he was arrested for refusing to take down anti-nuclear information from the union bulletin board at the shoe company. In a show of solidarity his fellow workers showed up a few days later wearing anti-nuclear buttons. The company caved, brought Kellman and two other workers who had been arrested back to work, paid them for their time off, and asked the county to drop the trespass charges against them. It was a clear victory for workplace democracy.

Perhaps his highest profile work was as an organizer and strategist for the paper workers' strike in Jay, Maine in 1987-88. This prolonged struggle was eventually lost by the workers who felt sold out by their own union leadership. But one thing Kellman learned from that struggle and from all of the other political movements he has been part of was the importance of culture to sustain the movement. Around Civil Rights, Peace, women's, anti-nuclear, gender, and pro-labor movements formed strong "counter-cultures"--music, story, poetry, values, spiritual practice, work ethic, community. But he makes the point that the Peace movement in this country has not succeeded because we have never really built a culture of peace.

Today Kellman is working on building a theory and practice of what he calls the "culture of agriculture." He thinks great attention must be paid to building a culture of local and organic agriculture so that this movement will build community and have deep identity. About his own farming now, he says his effort is not to be self-sufficient. He and his wife Rebekah want to grow much of their own food, but they want to be part of an interdependent agricultural community. Only this way will the movement grow and survive.

Peter Kellman says: "We need to recover the disappeared story of the struggle of common people to create a democratic culture. We need to inject into the current debate a vision of a just society where competition is replaced with cooperation, where greed is replaced with love allowing power to be shared by all."

One of the best ways to do this is to build cultures and communities around local agriculture, people feeding themselves and each other healthy food and caring for the health of the earth.

Editor's note: The artist's essay that follows accompanies the 'online unveiling'--exclusive to Common Dreams--of Shetterly's latest painting in his "Americans Who Tell the Truth" portrait series, presenting citizens throughout U.S. history who have courageously engaged in the social, environmental, or economic issues of their time. This painting of union organizer and food community builder Peter Kellman is his latest portrait of those who dedicated their lives to equality, freedom and justice. Posters of this portrait and others are now available at the artist's website.

Often one portrait subject in the Americans Who Tell the Truth project leads to another. Terry Tempest Williams suggested Edward Abbey. Howard Zinn said if he were making the paintings his first portrait would be Fanny Lou Hamer. And Richard Grossman told me about Peter Kellman, his collaborator in forming the 'Program on Corporations, Law and Democracy.' This program had been established to expose how corporations in the United States had used (and continue to use) their powerful financial influence to make that influence legal. The results of that legal influence include not only their much talked about "personhood" but also their legal power in relation to controlling labor rights and unions, pollution restrictions, executive compensation, tax policy, corporate welfare, media, and corporate responsibility. Often the issue of corporate responsibility is described as corporations legally internalizing profit and externalizing cost, or, as privatizing profit and socializing cost, i.e., a power company that make large profits selling energy, but saddles the community with environmental and health costs caused by their mining and production. And, when the special interests of corporations write the law, democracy disappears. The people never know till after the fact how laws have been structured to favor corporate power and profit, and the corporate media rarely reports on how the political system has been gamed.

One of the best little books on this subject turns out to be written by that labor leader and labor historian from Maine, Peter Kellman. It's called Building Unions: Past, Present and Future. Kellman was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1946 and was introduced to labor politics being pushed by his mother in his baby carriage on a picket line. Family conversation was about progressive politics, the struggles of labor, and how to create a just, democratic society. In his late teens he spent three months learning organic agriculture and socialist politics from Helen and Scott Nearing at their farm in Maine, then he went to south in 1965 to help with logistical support for the March on Selma led by Martin Luther King, Jr., and John Lewis. He stayed in Alabama to help build a free (integrated) library. He worked with the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) for a while, then helped organize protests against the Vietnam War and encouraged Draft resistance.

Back in Maine, Kellman began factory work and labor organizing. He was elected president of of Shoe Workers Local 82 fighting for workplace safety, fair wages and regular hours. He was also a major organizer in the Clamshell Alliance, the organization opposing the Seabrook, New Hampshire Nuclear Power Plant. Once he was arrested for refusing to take down anti-nuclear information from the union bulletin board at the shoe company. In a show of solidarity his fellow workers showed up a few days later wearing anti-nuclear buttons. The company caved, brought Kellman and two other workers who had been arrested back to work, paid them for their time off, and asked the county to drop the trespass charges against them. It was a clear victory for workplace democracy.

Perhaps his highest profile work was as an organizer and strategist for the paper workers' strike in Jay, Maine in 1987-88. This prolonged struggle was eventually lost by the workers who felt sold out by their own union leadership. But one thing Kellman learned from that struggle and from all of the other political movements he has been part of was the importance of culture to sustain the movement. Around Civil Rights, Peace, women's, anti-nuclear, gender, and pro-labor movements formed strong "counter-cultures"--music, story, poetry, values, spiritual practice, work ethic, community. But he makes the point that the Peace movement in this country has not succeeded because we have never really built a culture of peace.

Today Kellman is working on building a theory and practice of what he calls the "culture of agriculture." He thinks great attention must be paid to building a culture of local and organic agriculture so that this movement will build community and have deep identity. About his own farming now, he says his effort is not to be self-sufficient. He and his wife Rebekah want to grow much of their own food, but they want to be part of an interdependent agricultural community. Only this way will the movement grow and survive.

Peter Kellman says: "We need to recover the disappeared story of the struggle of common people to create a democratic culture. We need to inject into the current debate a vision of a just society where competition is replaced with cooperation, where greed is replaced with love allowing power to be shared by all."

One of the best ways to do this is to build cultures and communities around local agriculture, people feeding themselves and each other healthy food and caring for the health of the earth.