Yesterday, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) announced the first case of Ebola diagnosed in the United States. Almost on cue, panic and overreaction were rampant, most notably on social media. It would seem that this panic is what even prompted a member of Congress to tweet the following:

Representative Andy Harris is a medical doctor by training, but the fact that he felt the need to reiterate to his followers the science on how Ebola spreads is telling.

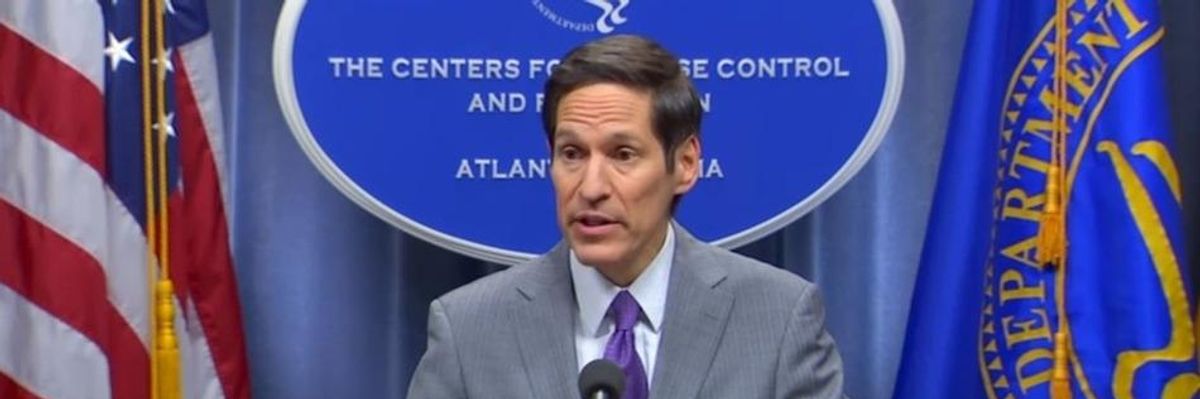

Indeed, this is a time when facts are more important than ever. And we need them to come from reliable sources. The CDC acted quickly yesterday with CDC Director Tom Freiden fielding questions from the media during a 5:30 pm press conference. There is no doubt staff at the agency have been preparing for this day for a long time. In fact, I can verify that they have.

"We need to be first, we need to be right."

Last April, I attended an internal training of CDC staff on how to communicate to the public during crisis situations. I listened intently as the CDC Public Affairs Director Barbara Reynolds explained the importance of "being first and being accurate" despite the many challenges of being both of these at the same time. I appreciated her emphasis on the importance of doing both because otherwise that void could be filled with information from others who don't have the public's interest in mind.

The training showed me that the agency takes their role in countering such misinformation seriously. And needless to say, that will be important here as we deal with a U.S. population who is fearful of a new disease on its soil.

When communication fails: the case of the Elk River chemical spill

In past crises, however, we haven't always seen quick and effective communication from federal agencies to the populations that need it. When chemicals spilled into West Virginia's Elk River last January, for example, the 300,000 people who relied on the river for their drinking water needed information and needed it fast. Was the water safe to drink? Was it safe to use at all? What should I do if my water has an odor?

Despite these pressing questions, many West Virginians were left without answers (or conflicting ones) when federal and state agencies remained silent about the risks posed by the chemical spill. Journalists attempted to contact government scientists but were stonewalled. Some scientists took matters into their own hands, but the end result was many communities left without the scientific information they needed to protect their health.

Freedom to speak: the importance of strong federal agency media policies

Scientists, especially those that work for federal agencies, should be able to speak to the public and to the media. There are agency concerns about the need for consistent messaging, but such concerns shouldn't trump the need to get scientific information from reliable sources in situations where public health is at stake.

To ensure that federal scientists have this ability, policies and practices at federal agencies need to be supportive. But the reality is that we see a wide range of quality in agency policies--from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA), which allows its experts to speak freely to the media, to the U.S. Department of Energy, which has a limited policy and appears to actively discourage its experts from communicating in some instances.

In the days that follow, we will undoubtedly see panic, fear, and misinformation in the U.S. but my hope is that we'll also see effective communication of science from government agencies and other reliable sources. I'd say the CDC has us off to a good start.