Community members confronted a line of police officers in Ferguson, Missouri during protests earlier this year.

(Photo: Robert Cohen, St. Louis Post-Dispatch/AP)

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Community members confronted a line of police officers in Ferguson, Missouri during protests earlier this year.

In Ferguson, Missouri, citizens and activists prepare for injustice, while government and law enforcement prepare for outraged reaction to injustice. But what about preparing for the justice Ferguson, and America, really needs?

As it waits to hear whether the grand jury will indict officer Darren Wilson in the death of unarmed black teenager Michael Brown, Ferguson is preparing for the worst: that the grand jury will decide not to indict Wilson, leading to more outrage and unrest in the streets of Ferguson.

Speculation over further unrest misses the point that the anger and frustration seen in Ferguson is much bigger than the death of Michael Brown or the indictment of Darren Wilson. As one, young Ferguson protestor put it, Michael Brown was just the final straw.

"We could just say Brown was the final straw; it was the straw that broke the camel's back," said Victoria Donaldson, 26, of St. Louis. "So until they fix that problem where young black men are being shot down or killed -- not even young black men, just black men in general -- are being completely disrespected and being treated like animals till the point of death, until that changes it will continue to be something that just upsets us."

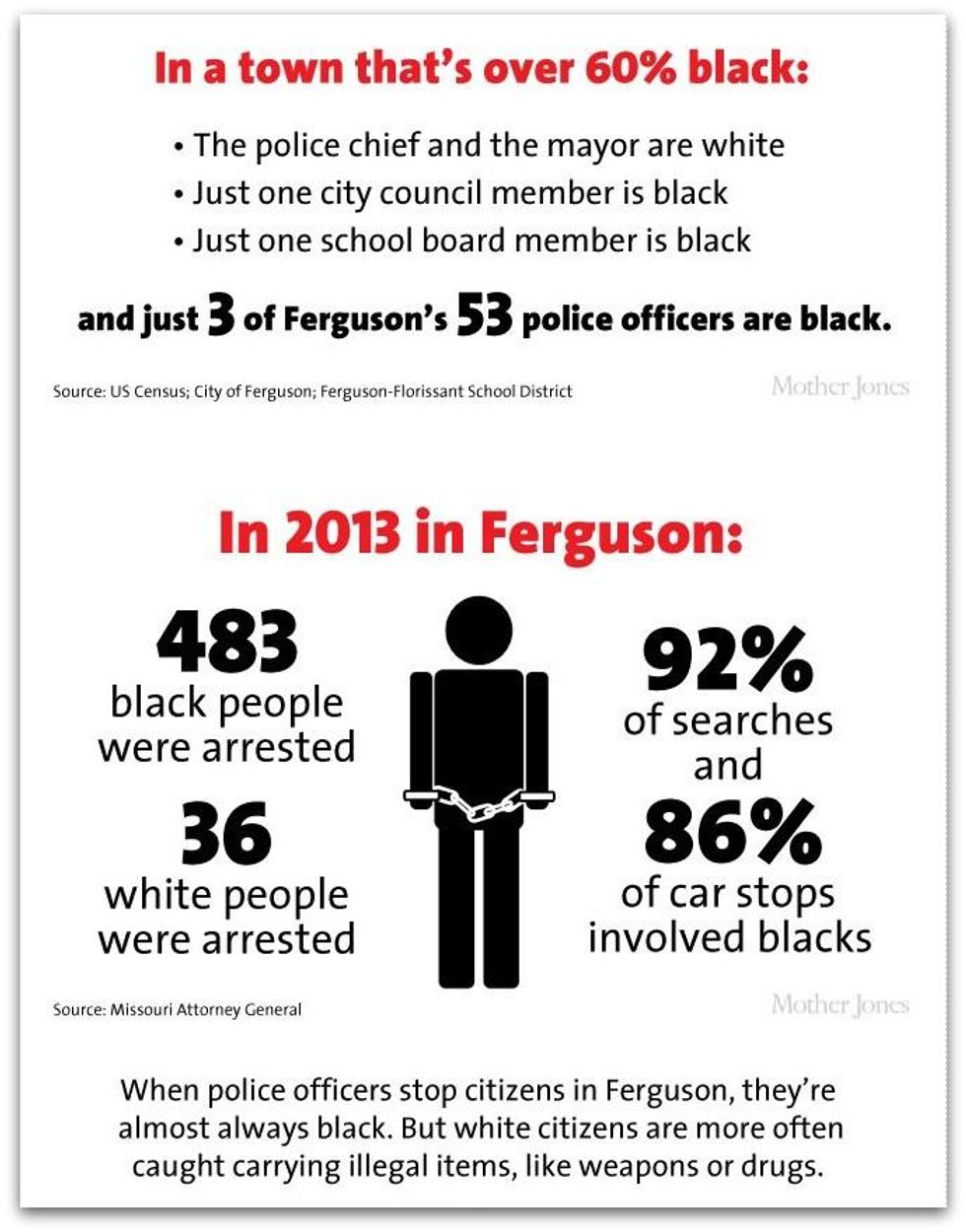

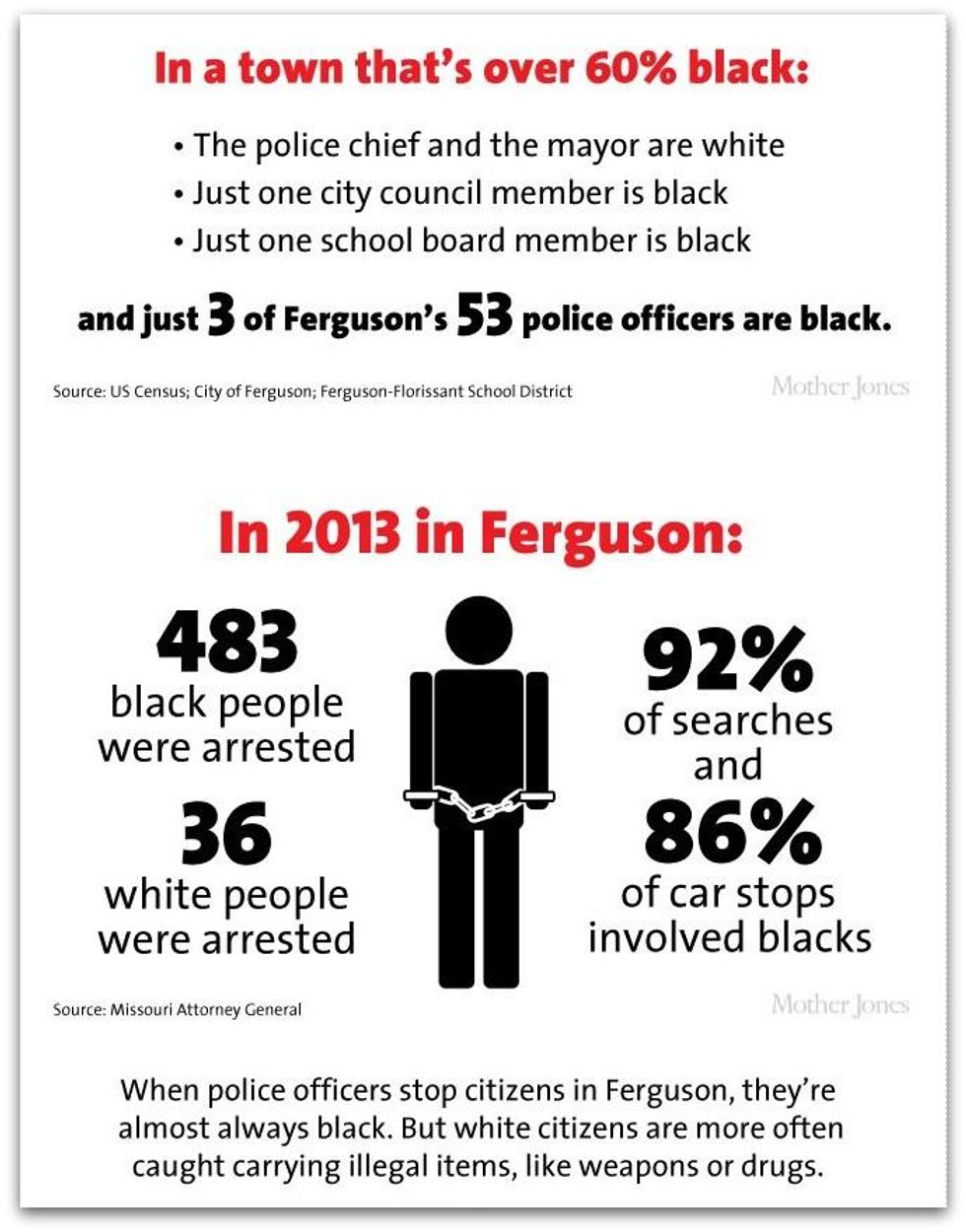

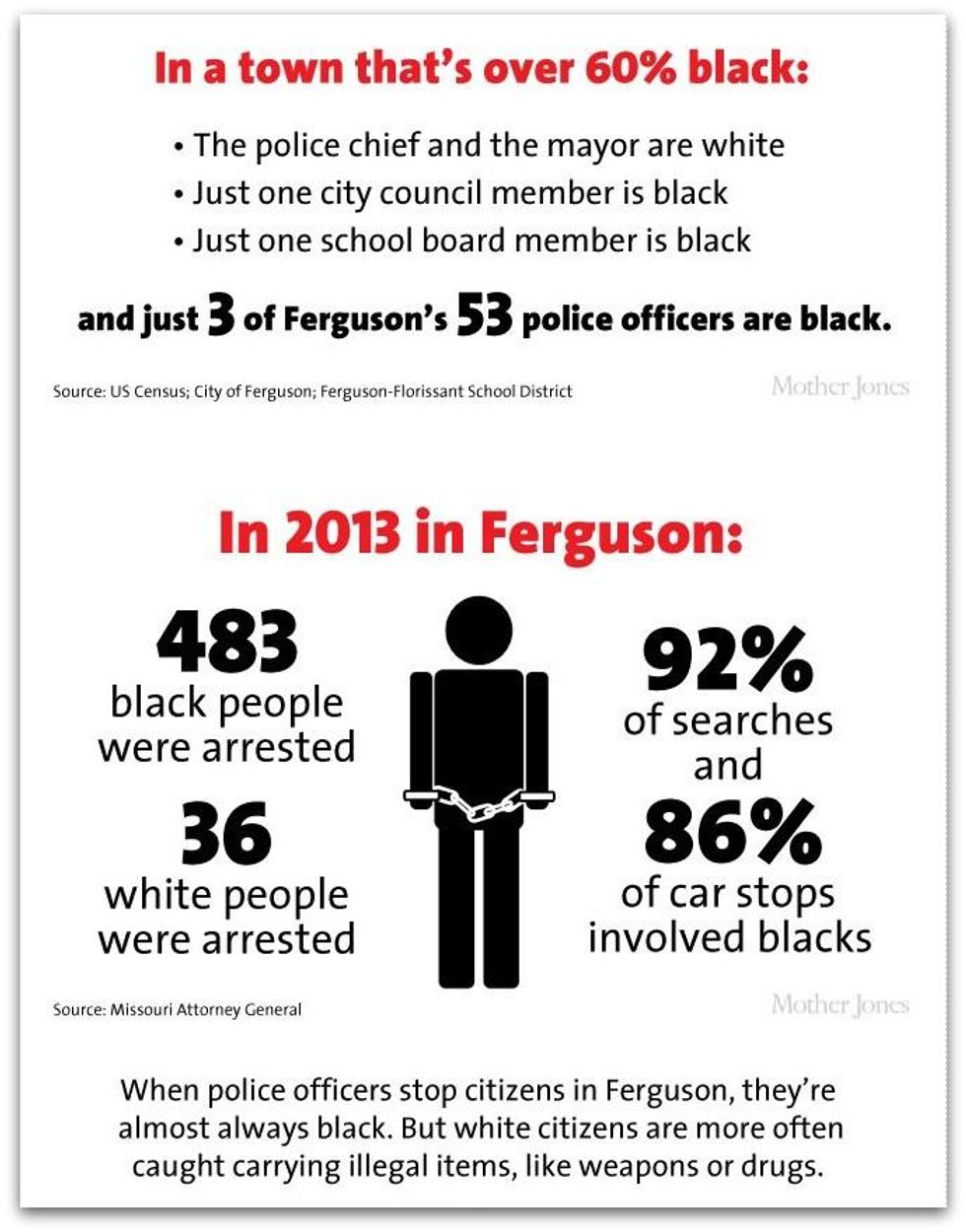

Ferguson was a city of stark racial disparities long before Michael Brown's death.

But the story of how it got that way isn't what we've been told in the media, as Richard Rothstein points out in his report, The Making of Ferguson: Public Policies at the Root of its Troubles. Media outlets blamed "white flight" for flipping inner-ring suburbs like Ferguson from white to black, and the private prejudices of white homeowners for keeping outer-ring suburbs white. "A more powerful cause," Rothstein writes, "is the explicit intents of federal, state, and local governments to create racially segregated metropolises."

Starting in the Jim Crow era, city planning councils prevented "colored people" from moving into "finer residential districts," and designated areas in, or adjacent to black neighborhoods for industrial development, and using industrial areas as a buffer between back and white neighborhoods. Black neighborhood were denied public services -- like streetlights, garbage collection, access to municipal water. Government policy effectively turned those neighborhoods into slums. White homeowners came to associate blacks with slum dwelling, leading to problems when black families tried to buy homes in white neighborhoods.

Crisis in Levittown, PAThis is a version of the landmark documentary "crisis in Levittown, PA" that I edited down to 10 minutes for my class.

By the 30s and 40s, cities began clearing slums to use for "better and higher purposes," like building waterfront development, highway exchanges, and universities. Meanwhile, the when the New Deal built the first public housing in America, the Public Works Administration's (PWA) "neighborhood composition rule" perpetuated municipal segregationist policies, by stipulating that public housing project could not alter the racial composition of the neighborhoods where they were built. The PWA even segregated its work crews across the country.

Blacks were pushed into areas like Ferguson. Meanwhile, whites moved to outer-suburbs, where restrictive covenants prohibited white homeowners from selling to blacks. These covenants began as private commitments between neighbors, but were soon adopted by real estate boards. The Federal Housing Administration (FHA) subsidized the mass production of suburbs, but would not guarantee loans to blacks.

By the 1950s, government policies had depopulated central cities of whites, and blacks replaced whites in public housing projects, like St. Louis' infamous Pruitt-Igoe towers.

It wasn't just housing policy. Rothstein writes that government support of a segregated labor market supplemented racist housing policies, and "prevented most African-American families from acquiring the economic strength to move into middle class neighborhoods," even if they'd been allowed to.

Again, the economic consequences are still with us, as Sherrliyn Ifill pointed out during EPI's "The Making of Ferguson" forum.

None of this is likely to be discussed in the event of unrest after the Ferguson grand jury's decision is announced. It was once well-known history, but it has been conveniently forgotten in favor of easy answers that blame "white flight" and a "culture of poverty" for the disparities that led to despair that exploded into outrage on the streets of Ferguson.

Preparing for outrage and injustice will not save Ferguson, or prevent the next city that's "one dead black teenager away" from becoming "the next Ferguson." Nor will, for that matter, an indictment. Nothing will truly prevent "the next Ferguson" until we decide to prepare for justice, by undoing the damage done by decades of policies that went into the making of Ferguson, and cities like it across the country.

Donald Trump’s attacks on democracy, justice, and a free press are escalating — putting everything we stand for at risk. We believe a better world is possible, but we can’t get there without your support. Common Dreams stands apart. We answer only to you — our readers, activists, and changemakers — not to billionaires or corporations. Our independence allows us to cover the vital stories that others won’t, spotlighting movements for peace, equality, and human rights. Right now, our work faces unprecedented challenges. Misinformation is spreading, journalists are under attack, and financial pressures are mounting. As a reader-supported, nonprofit newsroom, your support is crucial to keep this journalism alive. Whatever you can give — $10, $25, or $100 — helps us stay strong and responsive when the world needs us most. Together, we’ll continue to build the independent, courageous journalism our movement relies on. Thank you for being part of this community. |

In Ferguson, Missouri, citizens and activists prepare for injustice, while government and law enforcement prepare for outraged reaction to injustice. But what about preparing for the justice Ferguson, and America, really needs?

As it waits to hear whether the grand jury will indict officer Darren Wilson in the death of unarmed black teenager Michael Brown, Ferguson is preparing for the worst: that the grand jury will decide not to indict Wilson, leading to more outrage and unrest in the streets of Ferguson.

Speculation over further unrest misses the point that the anger and frustration seen in Ferguson is much bigger than the death of Michael Brown or the indictment of Darren Wilson. As one, young Ferguson protestor put it, Michael Brown was just the final straw.

"We could just say Brown was the final straw; it was the straw that broke the camel's back," said Victoria Donaldson, 26, of St. Louis. "So until they fix that problem where young black men are being shot down or killed -- not even young black men, just black men in general -- are being completely disrespected and being treated like animals till the point of death, until that changes it will continue to be something that just upsets us."

Ferguson was a city of stark racial disparities long before Michael Brown's death.

But the story of how it got that way isn't what we've been told in the media, as Richard Rothstein points out in his report, The Making of Ferguson: Public Policies at the Root of its Troubles. Media outlets blamed "white flight" for flipping inner-ring suburbs like Ferguson from white to black, and the private prejudices of white homeowners for keeping outer-ring suburbs white. "A more powerful cause," Rothstein writes, "is the explicit intents of federal, state, and local governments to create racially segregated metropolises."

Starting in the Jim Crow era, city planning councils prevented "colored people" from moving into "finer residential districts," and designated areas in, or adjacent to black neighborhoods for industrial development, and using industrial areas as a buffer between back and white neighborhoods. Black neighborhood were denied public services -- like streetlights, garbage collection, access to municipal water. Government policy effectively turned those neighborhoods into slums. White homeowners came to associate blacks with slum dwelling, leading to problems when black families tried to buy homes in white neighborhoods.

Crisis in Levittown, PAThis is a version of the landmark documentary "crisis in Levittown, PA" that I edited down to 10 minutes for my class.

By the 30s and 40s, cities began clearing slums to use for "better and higher purposes," like building waterfront development, highway exchanges, and universities. Meanwhile, the when the New Deal built the first public housing in America, the Public Works Administration's (PWA) "neighborhood composition rule" perpetuated municipal segregationist policies, by stipulating that public housing project could not alter the racial composition of the neighborhoods where they were built. The PWA even segregated its work crews across the country.

Blacks were pushed into areas like Ferguson. Meanwhile, whites moved to outer-suburbs, where restrictive covenants prohibited white homeowners from selling to blacks. These covenants began as private commitments between neighbors, but were soon adopted by real estate boards. The Federal Housing Administration (FHA) subsidized the mass production of suburbs, but would not guarantee loans to blacks.

By the 1950s, government policies had depopulated central cities of whites, and blacks replaced whites in public housing projects, like St. Louis' infamous Pruitt-Igoe towers.

It wasn't just housing policy. Rothstein writes that government support of a segregated labor market supplemented racist housing policies, and "prevented most African-American families from acquiring the economic strength to move into middle class neighborhoods," even if they'd been allowed to.

Again, the economic consequences are still with us, as Sherrliyn Ifill pointed out during EPI's "The Making of Ferguson" forum.

None of this is likely to be discussed in the event of unrest after the Ferguson grand jury's decision is announced. It was once well-known history, but it has been conveniently forgotten in favor of easy answers that blame "white flight" and a "culture of poverty" for the disparities that led to despair that exploded into outrage on the streets of Ferguson.

Preparing for outrage and injustice will not save Ferguson, or prevent the next city that's "one dead black teenager away" from becoming "the next Ferguson." Nor will, for that matter, an indictment. Nothing will truly prevent "the next Ferguson" until we decide to prepare for justice, by undoing the damage done by decades of policies that went into the making of Ferguson, and cities like it across the country.

In Ferguson, Missouri, citizens and activists prepare for injustice, while government and law enforcement prepare for outraged reaction to injustice. But what about preparing for the justice Ferguson, and America, really needs?

As it waits to hear whether the grand jury will indict officer Darren Wilson in the death of unarmed black teenager Michael Brown, Ferguson is preparing for the worst: that the grand jury will decide not to indict Wilson, leading to more outrage and unrest in the streets of Ferguson.

Speculation over further unrest misses the point that the anger and frustration seen in Ferguson is much bigger than the death of Michael Brown or the indictment of Darren Wilson. As one, young Ferguson protestor put it, Michael Brown was just the final straw.

"We could just say Brown was the final straw; it was the straw that broke the camel's back," said Victoria Donaldson, 26, of St. Louis. "So until they fix that problem where young black men are being shot down or killed -- not even young black men, just black men in general -- are being completely disrespected and being treated like animals till the point of death, until that changes it will continue to be something that just upsets us."

Ferguson was a city of stark racial disparities long before Michael Brown's death.

But the story of how it got that way isn't what we've been told in the media, as Richard Rothstein points out in his report, The Making of Ferguson: Public Policies at the Root of its Troubles. Media outlets blamed "white flight" for flipping inner-ring suburbs like Ferguson from white to black, and the private prejudices of white homeowners for keeping outer-ring suburbs white. "A more powerful cause," Rothstein writes, "is the explicit intents of federal, state, and local governments to create racially segregated metropolises."

Starting in the Jim Crow era, city planning councils prevented "colored people" from moving into "finer residential districts," and designated areas in, or adjacent to black neighborhoods for industrial development, and using industrial areas as a buffer between back and white neighborhoods. Black neighborhood were denied public services -- like streetlights, garbage collection, access to municipal water. Government policy effectively turned those neighborhoods into slums. White homeowners came to associate blacks with slum dwelling, leading to problems when black families tried to buy homes in white neighborhoods.

Crisis in Levittown, PAThis is a version of the landmark documentary "crisis in Levittown, PA" that I edited down to 10 minutes for my class.

By the 30s and 40s, cities began clearing slums to use for "better and higher purposes," like building waterfront development, highway exchanges, and universities. Meanwhile, the when the New Deal built the first public housing in America, the Public Works Administration's (PWA) "neighborhood composition rule" perpetuated municipal segregationist policies, by stipulating that public housing project could not alter the racial composition of the neighborhoods where they were built. The PWA even segregated its work crews across the country.

Blacks were pushed into areas like Ferguson. Meanwhile, whites moved to outer-suburbs, where restrictive covenants prohibited white homeowners from selling to blacks. These covenants began as private commitments between neighbors, but were soon adopted by real estate boards. The Federal Housing Administration (FHA) subsidized the mass production of suburbs, but would not guarantee loans to blacks.

By the 1950s, government policies had depopulated central cities of whites, and blacks replaced whites in public housing projects, like St. Louis' infamous Pruitt-Igoe towers.

It wasn't just housing policy. Rothstein writes that government support of a segregated labor market supplemented racist housing policies, and "prevented most African-American families from acquiring the economic strength to move into middle class neighborhoods," even if they'd been allowed to.

Again, the economic consequences are still with us, as Sherrliyn Ifill pointed out during EPI's "The Making of Ferguson" forum.

None of this is likely to be discussed in the event of unrest after the Ferguson grand jury's decision is announced. It was once well-known history, but it has been conveniently forgotten in favor of easy answers that blame "white flight" and a "culture of poverty" for the disparities that led to despair that exploded into outrage on the streets of Ferguson.

Preparing for outrage and injustice will not save Ferguson, or prevent the next city that's "one dead black teenager away" from becoming "the next Ferguson." Nor will, for that matter, an indictment. Nothing will truly prevent "the next Ferguson" until we decide to prepare for justice, by undoing the damage done by decades of policies that went into the making of Ferguson, and cities like it across the country.