SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

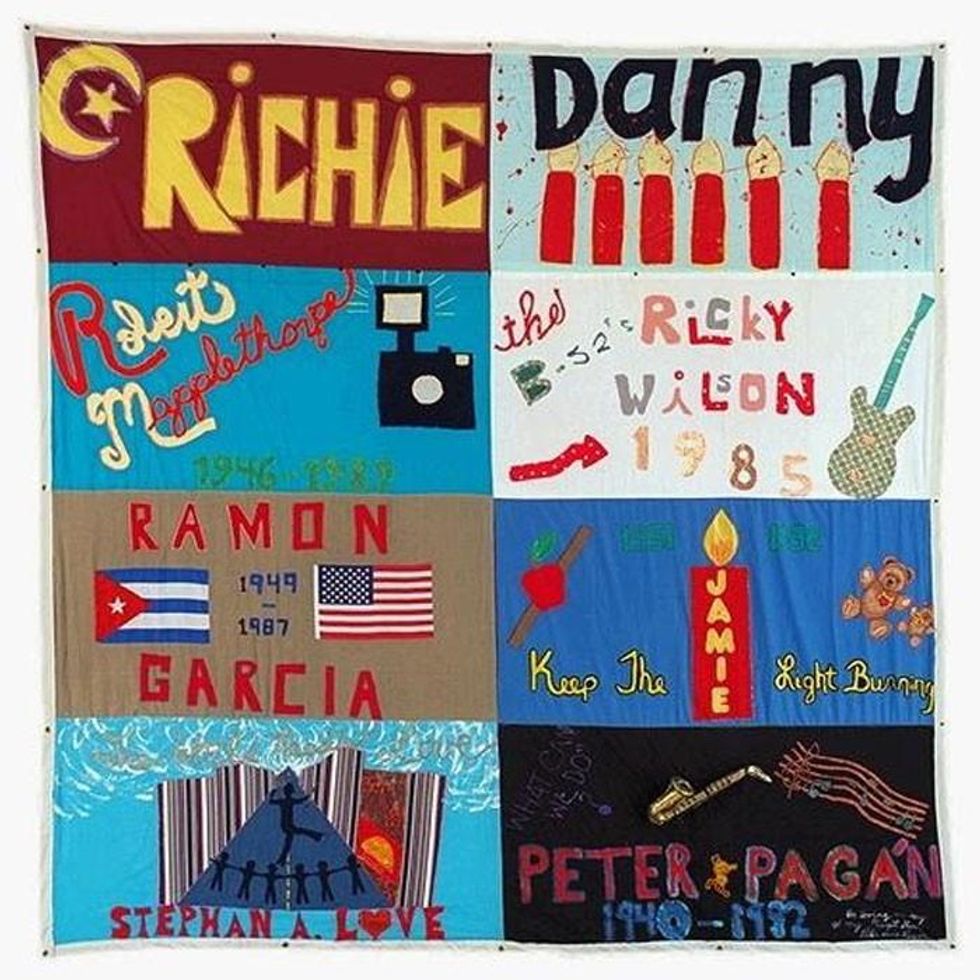

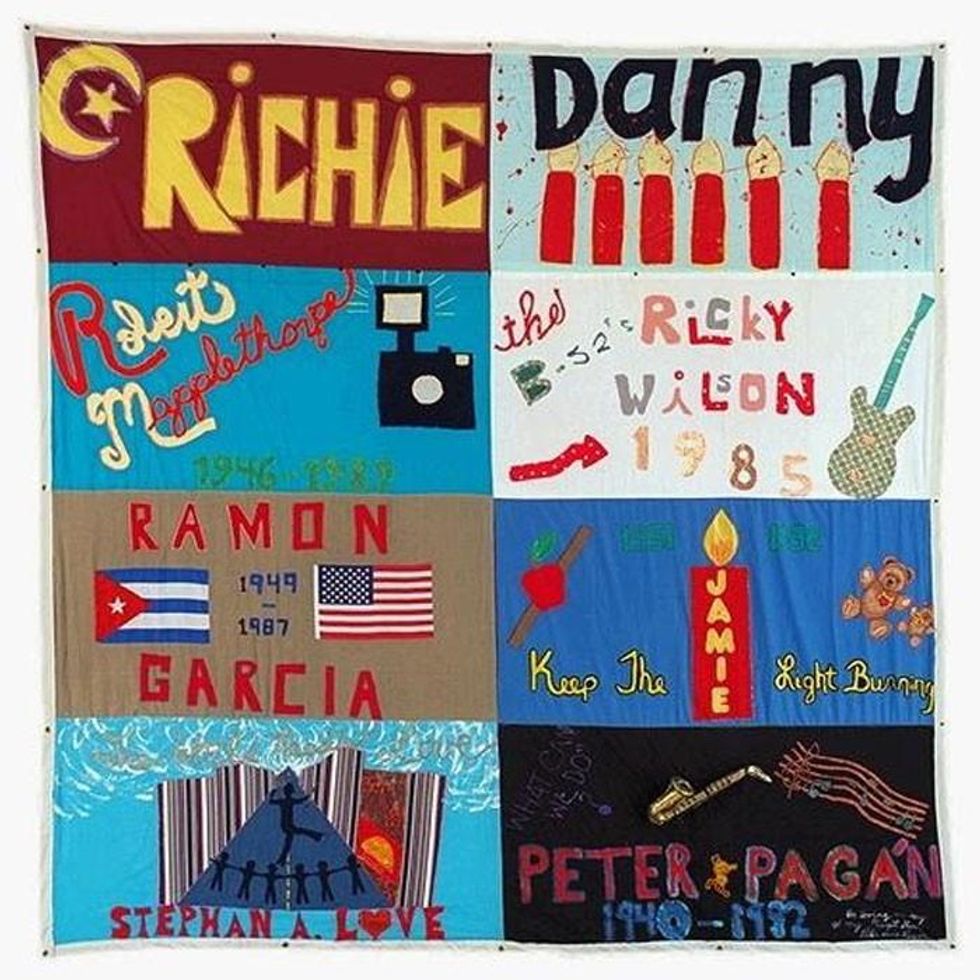

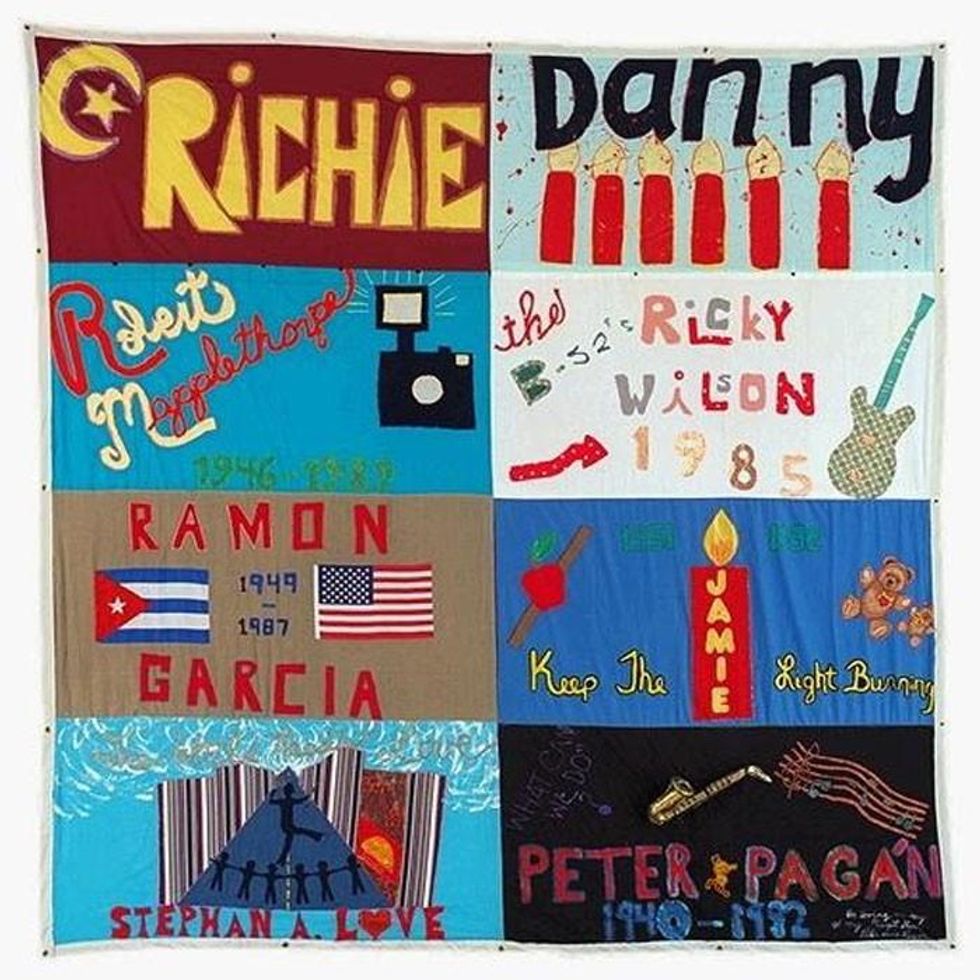

YMCA-YCI HIV/AIDS mural (Photo: YCI Canada / flickr)

The AIDS crisis was the first true epidemic of the era of globalization. Its rapid and devastating spread blasted through borders and stoked worldwide panic, in part because it seemed relatively democratic in its choice of victims, rich and poor alike. As the crisis "went viral" in a pre-Internet age, it both reflected and pushed the trend toward transnational social experience: as the casualties climbed with no cure in sight, HIV/AIDS challenged national boundaries and forced the public health community to seek solutions that could match the epidemic's borderless vector.

The AIDS crisis was the first true epidemic of the era of globalization. Its rapid and devastating spread blasted through borders and stoked worldwide panic, in part because it seemed relatively democratic in its choice of victims, rich and poor alike. As the crisis "went viral" in a pre-Internet age, it both reflected and pushed the trend toward transnational social experience: as the casualties climbed with no cure in sight, HIV/AIDS challenged national boundaries and forced the public health community to seek solutions that could match the epidemic's borderless vector.

And as we enter the second post-AIDS generation, we can take stock of how far activists, health workers, and survivors have journeyed and how far we have to go. There have been major advancements in treatment methods, and access for "developing" countries has improved. But there are still massive treatment gaps between Global North and South, and between rich and poor. In the United States, while infection rates have dropped, HIV continues to afflict poor communities of color, and the stigma and social tensions surrounding people living with HIV/AIDS still stand as a barrier to social services, employment, and equal treatment in the healthcare system. Stigma and other forms of discrimination hit especially hard in the LGBTQ community and for marginalized groups like sex workers and people involved with the criminal justice system. And for many immigrants around the world, HIV doesn't just lead to social barriers, it is the barrier.

Although HIV often coincides with other social hardships that can impede one's right to free movement across borders, the removal of the ban marked a step toward full recognition of the human rights of people living with HIV/AIDS. But there are places around the world where HIV remains a bar to entry and access. Some governments have even sought to deport people with HIV/AIDS - a disturbing convergence of draconian immigration enforcement policies, institutionalized discrimination, and social ignorance with profound public health effects.

According to a 2009 report by UNAIDS:

As shocking as the fact that such restrictions continue to exist are the harmful and various impacts that they have on people who endure them - mandatory testing without counselling or health care; denial of the opportunity to work or study abroad; deportation without notice leading to economic devastation; imprisonment; separation from family and loved ones; special "entry waivers" and application procedures; notification of HIV status in immigration documents. Such measures are discriminatory and represent a violation of international human rights standards. They can deprive people of their dignity and health, and there is no evidence that they protect the public health.

And for migrants caught in a legal limbo between borders, such as refugees fleeing conflict, HIV/AIDS forces them into potentially lethal isolation - perhaps deprived of medicine, or pushed into coercive testing or degrading treatment by healthcare institutions. Whether they face physical or social exile, the people impacted by this global pandemic struggle against both subsurface prejudices and hardened borders.

Such restrictions are a symptom of the underlying inequalities reinforced by border policies. Until all are able to reach across those bounds - to connect with loved ones, to access the resources they need to support their health and livelihoods, and to share their insights into global social problems without fear - we're all at risk of the plague of closed minds.

Political revenge. Mass deportations. Project 2025. Unfathomable corruption. Attacks on Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. Pardons for insurrectionists. An all-out assault on democracy. Republicans in Congress are scrambling to give Trump broad new powers to strip the tax-exempt status of any nonprofit he doesn’t like by declaring it a “terrorist-supporting organization.” Trump has already begun filing lawsuits against news outlets that criticize him. At Common Dreams, we won’t back down, but we must get ready for whatever Trump and his thugs throw at us. Our Year-End campaign is our most important fundraiser of the year. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. By donating today, please help us fight the dangers of a second Trump presidency. |

The AIDS crisis was the first true epidemic of the era of globalization. Its rapid and devastating spread blasted through borders and stoked worldwide panic, in part because it seemed relatively democratic in its choice of victims, rich and poor alike. As the crisis "went viral" in a pre-Internet age, it both reflected and pushed the trend toward transnational social experience: as the casualties climbed with no cure in sight, HIV/AIDS challenged national boundaries and forced the public health community to seek solutions that could match the epidemic's borderless vector.

And as we enter the second post-AIDS generation, we can take stock of how far activists, health workers, and survivors have journeyed and how far we have to go. There have been major advancements in treatment methods, and access for "developing" countries has improved. But there are still massive treatment gaps between Global North and South, and between rich and poor. In the United States, while infection rates have dropped, HIV continues to afflict poor communities of color, and the stigma and social tensions surrounding people living with HIV/AIDS still stand as a barrier to social services, employment, and equal treatment in the healthcare system. Stigma and other forms of discrimination hit especially hard in the LGBTQ community and for marginalized groups like sex workers and people involved with the criminal justice system. And for many immigrants around the world, HIV doesn't just lead to social barriers, it is the barrier.

Although HIV often coincides with other social hardships that can impede one's right to free movement across borders, the removal of the ban marked a step toward full recognition of the human rights of people living with HIV/AIDS. But there are places around the world where HIV remains a bar to entry and access. Some governments have even sought to deport people with HIV/AIDS - a disturbing convergence of draconian immigration enforcement policies, institutionalized discrimination, and social ignorance with profound public health effects.

According to a 2009 report by UNAIDS:

As shocking as the fact that such restrictions continue to exist are the harmful and various impacts that they have on people who endure them - mandatory testing without counselling or health care; denial of the opportunity to work or study abroad; deportation without notice leading to economic devastation; imprisonment; separation from family and loved ones; special "entry waivers" and application procedures; notification of HIV status in immigration documents. Such measures are discriminatory and represent a violation of international human rights standards. They can deprive people of their dignity and health, and there is no evidence that they protect the public health.

And for migrants caught in a legal limbo between borders, such as refugees fleeing conflict, HIV/AIDS forces them into potentially lethal isolation - perhaps deprived of medicine, or pushed into coercive testing or degrading treatment by healthcare institutions. Whether they face physical or social exile, the people impacted by this global pandemic struggle against both subsurface prejudices and hardened borders.

Such restrictions are a symptom of the underlying inequalities reinforced by border policies. Until all are able to reach across those bounds - to connect with loved ones, to access the resources they need to support their health and livelihoods, and to share their insights into global social problems without fear - we're all at risk of the plague of closed minds.

The AIDS crisis was the first true epidemic of the era of globalization. Its rapid and devastating spread blasted through borders and stoked worldwide panic, in part because it seemed relatively democratic in its choice of victims, rich and poor alike. As the crisis "went viral" in a pre-Internet age, it both reflected and pushed the trend toward transnational social experience: as the casualties climbed with no cure in sight, HIV/AIDS challenged national boundaries and forced the public health community to seek solutions that could match the epidemic's borderless vector.

And as we enter the second post-AIDS generation, we can take stock of how far activists, health workers, and survivors have journeyed and how far we have to go. There have been major advancements in treatment methods, and access for "developing" countries has improved. But there are still massive treatment gaps between Global North and South, and between rich and poor. In the United States, while infection rates have dropped, HIV continues to afflict poor communities of color, and the stigma and social tensions surrounding people living with HIV/AIDS still stand as a barrier to social services, employment, and equal treatment in the healthcare system. Stigma and other forms of discrimination hit especially hard in the LGBTQ community and for marginalized groups like sex workers and people involved with the criminal justice system. And for many immigrants around the world, HIV doesn't just lead to social barriers, it is the barrier.

Although HIV often coincides with other social hardships that can impede one's right to free movement across borders, the removal of the ban marked a step toward full recognition of the human rights of people living with HIV/AIDS. But there are places around the world where HIV remains a bar to entry and access. Some governments have even sought to deport people with HIV/AIDS - a disturbing convergence of draconian immigration enforcement policies, institutionalized discrimination, and social ignorance with profound public health effects.

According to a 2009 report by UNAIDS:

As shocking as the fact that such restrictions continue to exist are the harmful and various impacts that they have on people who endure them - mandatory testing without counselling or health care; denial of the opportunity to work or study abroad; deportation without notice leading to economic devastation; imprisonment; separation from family and loved ones; special "entry waivers" and application procedures; notification of HIV status in immigration documents. Such measures are discriminatory and represent a violation of international human rights standards. They can deprive people of their dignity and health, and there is no evidence that they protect the public health.

And for migrants caught in a legal limbo between borders, such as refugees fleeing conflict, HIV/AIDS forces them into potentially lethal isolation - perhaps deprived of medicine, or pushed into coercive testing or degrading treatment by healthcare institutions. Whether they face physical or social exile, the people impacted by this global pandemic struggle against both subsurface prejudices and hardened borders.

Such restrictions are a symptom of the underlying inequalities reinforced by border policies. Until all are able to reach across those bounds - to connect with loved ones, to access the resources they need to support their health and livelihoods, and to share their insights into global social problems without fear - we're all at risk of the plague of closed minds.