SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

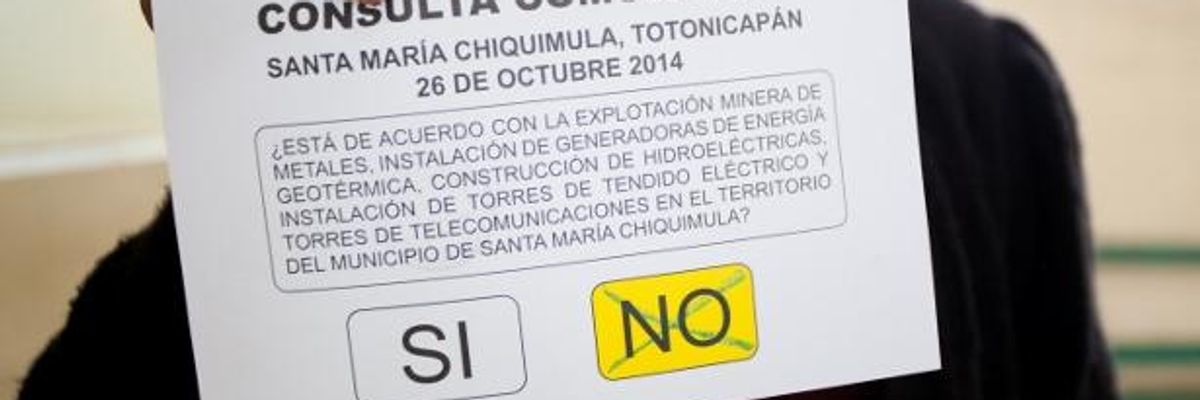

A woman holds up her ballot to show that she voted against mining projects within the territory. (Photo: WNV/Jeff Abbott)

Conflicts over mining are expanding across Guatemala. According to a recent report by Amnesty International, the Canadian government and Canada-based multinational mining companies have played a major role in the conflicts and abuses of human rights in indigenous communities.

"Canada -- like many other states -- has shown itself willing to take action with extraterritorial effect to promote and protect corporate interests," state the authors of the Amnesty International report. "The failure to take action -- in line with the requirements and recommendations of U.N. human rights treaty bodies -- to effectively regulate Canadian companies operating abroad is enabling these companies to benefit from human rights abuses occurring outside of Canada."

The report, which was published in September 2014, states that Canada, which is headquarters for three-quarters of global mining companies, and the government of Guatemala have failed to provide space for community involvement and voices in the expansion of mining. The inadequate protection and unwillingness of the Guatemalan government of President Otto Perez Molina to guarantee the rights of indigenous communities has exacerbated the situation.

"In promoting the involvement of Canadian corporations in global resource extraction activities, the government of Canada continues to rely almost exclusively on the national laws, regulations and enforcement mechanisms of the host countries to ensure that Canadian investment abroad does not contribute to human rights abuses," states the Amnesty International report, "even when there is reason to believe that those laws are inadequate or are not enforced."

The right to be consulted

For the indigenous Mayan communities of Guatemala, the process of participatory decision-making takes the form of the community consulta, or consultation, which has played an important role in the interactions between indigenous peoples and the government.

According to articles 1, 66, and 67 of the Guatemalan constitution, the government is required to respect indigenous land and protect their communal ownership system. In the event that a mining permit is issued on the land of indigenous communities, the government must consult the population two weeks prior to the issuing of permits for explorations.

This process is supported by several international laws and declarations on the rights of indigenous communities by the United Nations and the International Labor Organization, which require that the government consult the communities prior to issuing permits for exploration or exploitation of resources. Article 18 of the U.N. Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, for example, states that "Indigenous peoples have the right to participate in decision-making in matters which would affect their rights, through representatives chosen by themselves in accordance with their own procedures."

Despite these laws, and the fact that Guatemala is a signatory to these international declarations, the government has done little to consult the communities affected by mining operations.

In the face of growing social conflict over mining, communities have organized to defend their land from the interests of multinational companies, and have chosen to declare their resistance to extractive projects that threaten the environment and their livelihoods.

Since 2006, the Consejo de los Pueblos Occidentes, or CPO, is one Guatemalan organization that has been at the forefront of the movement in defense of indigenous territory. "According to the law, the Guatemalan government is obliged to consult the indigenous communities prior to the passing of any law," said Nim Sanik, of the Kaqchikel Maya branch of the CPO in the department of Chimaltenango. "But we have never been consulted."

By failing to consult the communities on the development projects, the Mayan organization points out that the Guatemalan state is in violation of international law. This failure, however, has not stopped the communities from holding their own consultation in what the spokesman of the indigenous community of Cantel, Quetzaltenago referred to in a press conference as a "deeply and profoundly democratic process."

Community direct democracy

On the chilly morning of October 26 in the highland municipality of Santa Maria Chiquimula about 125 miles from Guatemala City, residents came out to participate in a community vote deciding whether or not they would resist the exploitation of natural resources.

The consultation was held in response to the Guatemalan government's issuing of a permit to a Guatemalan subsidiary of the Italian mining firm Enel for the exploration of geothermic energy within the municipality. As in past cases, the government failed to consult the indigenous people prior to issuing the permit.

The practice of the community consultation represents a form of indigenous direct democracy, which Sanik refers to as a "non-Western form of social organization." It also serves as an important tool to the indigenous communities as they organize to defend their lives and territory.

According to Sanik, the process of the community consultation comes from the Kiche Mayan holy book the "Popol Vuh." In a consulta, every resident within a community over the age of seven has a vote and a part in the decision making process for the community. The large consultas can take months to plan to ensure that everyone is equally informed about what the vote is on. In the end, the results represent the consensus of the community.

Efforts to limit the consulta

Not only has the Guatemalan government made little effort to listen to the community's concerns and decisions -- despite the regular community consultations and the constitutional right of consultation -- it has taken steps to limit the right of the consulta.

In 2005, the indigenous communities of Sipakapa in the department of San Marcos held a consulta on a mining project in their territory. They voted unanimously to resist the project, but the government did not respect the community's decision and issued a permit for the Los Chocoyos mining project to a Guatemalan subsidiary of the Canadian mining firm Goldcorp.

Communities have responded by demanding the Guatemalan Congress pass a law protecting their right to consultation. Indigenous rights activists have found support in Guatemala's Constitutional Court, which in 2010 ruled in favor of the indigenous communities, citing Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization in their decision. The court's finding states that the Guatemalan government is violating the rights of indigenous peoples by failing to consult the communities prior to the issuing of permits for exploration and exploitation of mineral resources.

"The Ministry of Energy and Mining must take into account the right to consultation of indigenous peoples before issuing mining licenses," the court's decision read. "Government agencies must simply comply with [the right to consultation]."

Voting yes to life, and no to mining

Communities have increasingly returned to the consulta to express their disapproval of mining and extractive projects in their territories. The consultation held in Santa Maria Chiquimula is the 73rd consultation held since 2005 within the Mayan communities of Guatemala. In each case, the communities have voted overwhelming against the mega-projects in their territories. For residents, it is yes to life, and no to mining.

Back in Santa Maria Chiquimula, by the end of the day, the 40,000 residents overwhelmingly declared their resistance to mining operations within their communities, with over 39,000 people voting against the exploitation of natural resources in the area. From young to old, community members expressed a deep understanding of what the mining operations would mean for their livelihoods and environment.

"We vote no for our children," said Maria, a resident of Santa Maria Chiquimula. "We've read about the negative health impacts from the mining operations in the department of San Marcos, and environmental effects of other projects. We don't want to see those consequences in our community. That is why we are here to vote no to mining near Santa Maria Chiquimula."

On November 4, the community leaders of the 18 communities of Santa Maria Chiquimula delivered the official results of the consulta to governmental ministries, including members of the congressional commission on indigenous peoples, the minister of mining and energy, and the minister of natural resources.

"The people demonstrated their rejection of these types of projects," said Jose Carlos Carrillas, the spokesman of the communities. "Because we believe that [this type of] development to our communities only provokes exploitation of the mediums of life, the division of the people, and the increase of social and economic inequality."

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

Conflicts over mining are expanding across Guatemala. According to a recent report by Amnesty International, the Canadian government and Canada-based multinational mining companies have played a major role in the conflicts and abuses of human rights in indigenous communities.

"Canada -- like many other states -- has shown itself willing to take action with extraterritorial effect to promote and protect corporate interests," state the authors of the Amnesty International report. "The failure to take action -- in line with the requirements and recommendations of U.N. human rights treaty bodies -- to effectively regulate Canadian companies operating abroad is enabling these companies to benefit from human rights abuses occurring outside of Canada."

The report, which was published in September 2014, states that Canada, which is headquarters for three-quarters of global mining companies, and the government of Guatemala have failed to provide space for community involvement and voices in the expansion of mining. The inadequate protection and unwillingness of the Guatemalan government of President Otto Perez Molina to guarantee the rights of indigenous communities has exacerbated the situation.

"In promoting the involvement of Canadian corporations in global resource extraction activities, the government of Canada continues to rely almost exclusively on the national laws, regulations and enforcement mechanisms of the host countries to ensure that Canadian investment abroad does not contribute to human rights abuses," states the Amnesty International report, "even when there is reason to believe that those laws are inadequate or are not enforced."

The right to be consulted

For the indigenous Mayan communities of Guatemala, the process of participatory decision-making takes the form of the community consulta, or consultation, which has played an important role in the interactions between indigenous peoples and the government.

According to articles 1, 66, and 67 of the Guatemalan constitution, the government is required to respect indigenous land and protect their communal ownership system. In the event that a mining permit is issued on the land of indigenous communities, the government must consult the population two weeks prior to the issuing of permits for explorations.

This process is supported by several international laws and declarations on the rights of indigenous communities by the United Nations and the International Labor Organization, which require that the government consult the communities prior to issuing permits for exploration or exploitation of resources. Article 18 of the U.N. Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, for example, states that "Indigenous peoples have the right to participate in decision-making in matters which would affect their rights, through representatives chosen by themselves in accordance with their own procedures."

Despite these laws, and the fact that Guatemala is a signatory to these international declarations, the government has done little to consult the communities affected by mining operations.

In the face of growing social conflict over mining, communities have organized to defend their land from the interests of multinational companies, and have chosen to declare their resistance to extractive projects that threaten the environment and their livelihoods.

Since 2006, the Consejo de los Pueblos Occidentes, or CPO, is one Guatemalan organization that has been at the forefront of the movement in defense of indigenous territory. "According to the law, the Guatemalan government is obliged to consult the indigenous communities prior to the passing of any law," said Nim Sanik, of the Kaqchikel Maya branch of the CPO in the department of Chimaltenango. "But we have never been consulted."

By failing to consult the communities on the development projects, the Mayan organization points out that the Guatemalan state is in violation of international law. This failure, however, has not stopped the communities from holding their own consultation in what the spokesman of the indigenous community of Cantel, Quetzaltenago referred to in a press conference as a "deeply and profoundly democratic process."

Community direct democracy

On the chilly morning of October 26 in the highland municipality of Santa Maria Chiquimula about 125 miles from Guatemala City, residents came out to participate in a community vote deciding whether or not they would resist the exploitation of natural resources.

The consultation was held in response to the Guatemalan government's issuing of a permit to a Guatemalan subsidiary of the Italian mining firm Enel for the exploration of geothermic energy within the municipality. As in past cases, the government failed to consult the indigenous people prior to issuing the permit.

The practice of the community consultation represents a form of indigenous direct democracy, which Sanik refers to as a "non-Western form of social organization." It also serves as an important tool to the indigenous communities as they organize to defend their lives and territory.

According to Sanik, the process of the community consultation comes from the Kiche Mayan holy book the "Popol Vuh." In a consulta, every resident within a community over the age of seven has a vote and a part in the decision making process for the community. The large consultas can take months to plan to ensure that everyone is equally informed about what the vote is on. In the end, the results represent the consensus of the community.

Efforts to limit the consulta

Not only has the Guatemalan government made little effort to listen to the community's concerns and decisions -- despite the regular community consultations and the constitutional right of consultation -- it has taken steps to limit the right of the consulta.

In 2005, the indigenous communities of Sipakapa in the department of San Marcos held a consulta on a mining project in their territory. They voted unanimously to resist the project, but the government did not respect the community's decision and issued a permit for the Los Chocoyos mining project to a Guatemalan subsidiary of the Canadian mining firm Goldcorp.

Communities have responded by demanding the Guatemalan Congress pass a law protecting their right to consultation. Indigenous rights activists have found support in Guatemala's Constitutional Court, which in 2010 ruled in favor of the indigenous communities, citing Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization in their decision. The court's finding states that the Guatemalan government is violating the rights of indigenous peoples by failing to consult the communities prior to the issuing of permits for exploration and exploitation of mineral resources.

"The Ministry of Energy and Mining must take into account the right to consultation of indigenous peoples before issuing mining licenses," the court's decision read. "Government agencies must simply comply with [the right to consultation]."

Voting yes to life, and no to mining

Communities have increasingly returned to the consulta to express their disapproval of mining and extractive projects in their territories. The consultation held in Santa Maria Chiquimula is the 73rd consultation held since 2005 within the Mayan communities of Guatemala. In each case, the communities have voted overwhelming against the mega-projects in their territories. For residents, it is yes to life, and no to mining.

Back in Santa Maria Chiquimula, by the end of the day, the 40,000 residents overwhelmingly declared their resistance to mining operations within their communities, with over 39,000 people voting against the exploitation of natural resources in the area. From young to old, community members expressed a deep understanding of what the mining operations would mean for their livelihoods and environment.

"We vote no for our children," said Maria, a resident of Santa Maria Chiquimula. "We've read about the negative health impacts from the mining operations in the department of San Marcos, and environmental effects of other projects. We don't want to see those consequences in our community. That is why we are here to vote no to mining near Santa Maria Chiquimula."

On November 4, the community leaders of the 18 communities of Santa Maria Chiquimula delivered the official results of the consulta to governmental ministries, including members of the congressional commission on indigenous peoples, the minister of mining and energy, and the minister of natural resources.

"The people demonstrated their rejection of these types of projects," said Jose Carlos Carrillas, the spokesman of the communities. "Because we believe that [this type of] development to our communities only provokes exploitation of the mediums of life, the division of the people, and the increase of social and economic inequality."

Conflicts over mining are expanding across Guatemala. According to a recent report by Amnesty International, the Canadian government and Canada-based multinational mining companies have played a major role in the conflicts and abuses of human rights in indigenous communities.

"Canada -- like many other states -- has shown itself willing to take action with extraterritorial effect to promote and protect corporate interests," state the authors of the Amnesty International report. "The failure to take action -- in line with the requirements and recommendations of U.N. human rights treaty bodies -- to effectively regulate Canadian companies operating abroad is enabling these companies to benefit from human rights abuses occurring outside of Canada."

The report, which was published in September 2014, states that Canada, which is headquarters for three-quarters of global mining companies, and the government of Guatemala have failed to provide space for community involvement and voices in the expansion of mining. The inadequate protection and unwillingness of the Guatemalan government of President Otto Perez Molina to guarantee the rights of indigenous communities has exacerbated the situation.

"In promoting the involvement of Canadian corporations in global resource extraction activities, the government of Canada continues to rely almost exclusively on the national laws, regulations and enforcement mechanisms of the host countries to ensure that Canadian investment abroad does not contribute to human rights abuses," states the Amnesty International report, "even when there is reason to believe that those laws are inadequate or are not enforced."

The right to be consulted

For the indigenous Mayan communities of Guatemala, the process of participatory decision-making takes the form of the community consulta, or consultation, which has played an important role in the interactions between indigenous peoples and the government.

According to articles 1, 66, and 67 of the Guatemalan constitution, the government is required to respect indigenous land and protect their communal ownership system. In the event that a mining permit is issued on the land of indigenous communities, the government must consult the population two weeks prior to the issuing of permits for explorations.

This process is supported by several international laws and declarations on the rights of indigenous communities by the United Nations and the International Labor Organization, which require that the government consult the communities prior to issuing permits for exploration or exploitation of resources. Article 18 of the U.N. Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, for example, states that "Indigenous peoples have the right to participate in decision-making in matters which would affect their rights, through representatives chosen by themselves in accordance with their own procedures."

Despite these laws, and the fact that Guatemala is a signatory to these international declarations, the government has done little to consult the communities affected by mining operations.

In the face of growing social conflict over mining, communities have organized to defend their land from the interests of multinational companies, and have chosen to declare their resistance to extractive projects that threaten the environment and their livelihoods.

Since 2006, the Consejo de los Pueblos Occidentes, or CPO, is one Guatemalan organization that has been at the forefront of the movement in defense of indigenous territory. "According to the law, the Guatemalan government is obliged to consult the indigenous communities prior to the passing of any law," said Nim Sanik, of the Kaqchikel Maya branch of the CPO in the department of Chimaltenango. "But we have never been consulted."

By failing to consult the communities on the development projects, the Mayan organization points out that the Guatemalan state is in violation of international law. This failure, however, has not stopped the communities from holding their own consultation in what the spokesman of the indigenous community of Cantel, Quetzaltenago referred to in a press conference as a "deeply and profoundly democratic process."

Community direct democracy

On the chilly morning of October 26 in the highland municipality of Santa Maria Chiquimula about 125 miles from Guatemala City, residents came out to participate in a community vote deciding whether or not they would resist the exploitation of natural resources.

The consultation was held in response to the Guatemalan government's issuing of a permit to a Guatemalan subsidiary of the Italian mining firm Enel for the exploration of geothermic energy within the municipality. As in past cases, the government failed to consult the indigenous people prior to issuing the permit.

The practice of the community consultation represents a form of indigenous direct democracy, which Sanik refers to as a "non-Western form of social organization." It also serves as an important tool to the indigenous communities as they organize to defend their lives and territory.

According to Sanik, the process of the community consultation comes from the Kiche Mayan holy book the "Popol Vuh." In a consulta, every resident within a community over the age of seven has a vote and a part in the decision making process for the community. The large consultas can take months to plan to ensure that everyone is equally informed about what the vote is on. In the end, the results represent the consensus of the community.

Efforts to limit the consulta

Not only has the Guatemalan government made little effort to listen to the community's concerns and decisions -- despite the regular community consultations and the constitutional right of consultation -- it has taken steps to limit the right of the consulta.

In 2005, the indigenous communities of Sipakapa in the department of San Marcos held a consulta on a mining project in their territory. They voted unanimously to resist the project, but the government did not respect the community's decision and issued a permit for the Los Chocoyos mining project to a Guatemalan subsidiary of the Canadian mining firm Goldcorp.

Communities have responded by demanding the Guatemalan Congress pass a law protecting their right to consultation. Indigenous rights activists have found support in Guatemala's Constitutional Court, which in 2010 ruled in favor of the indigenous communities, citing Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization in their decision. The court's finding states that the Guatemalan government is violating the rights of indigenous peoples by failing to consult the communities prior to the issuing of permits for exploration and exploitation of mineral resources.

"The Ministry of Energy and Mining must take into account the right to consultation of indigenous peoples before issuing mining licenses," the court's decision read. "Government agencies must simply comply with [the right to consultation]."

Voting yes to life, and no to mining

Communities have increasingly returned to the consulta to express their disapproval of mining and extractive projects in their territories. The consultation held in Santa Maria Chiquimula is the 73rd consultation held since 2005 within the Mayan communities of Guatemala. In each case, the communities have voted overwhelming against the mega-projects in their territories. For residents, it is yes to life, and no to mining.

Back in Santa Maria Chiquimula, by the end of the day, the 40,000 residents overwhelmingly declared their resistance to mining operations within their communities, with over 39,000 people voting against the exploitation of natural resources in the area. From young to old, community members expressed a deep understanding of what the mining operations would mean for their livelihoods and environment.

"We vote no for our children," said Maria, a resident of Santa Maria Chiquimula. "We've read about the negative health impacts from the mining operations in the department of San Marcos, and environmental effects of other projects. We don't want to see those consequences in our community. That is why we are here to vote no to mining near Santa Maria Chiquimula."

On November 4, the community leaders of the 18 communities of Santa Maria Chiquimula delivered the official results of the consulta to governmental ministries, including members of the congressional commission on indigenous peoples, the minister of mining and energy, and the minister of natural resources.

"The people demonstrated their rejection of these types of projects," said Jose Carlos Carrillas, the spokesman of the communities. "Because we believe that [this type of] development to our communities only provokes exploitation of the mediums of life, the division of the people, and the increase of social and economic inequality."