A Muslim Cartoonist Draws Lessons from the Charlie Hebdo Massacre

Bullets and bombs can never silence the voices of laughter and friendship

As a political cartoonist who happens to be both American and Muslim, I often find myself at the intersection of media curiosity: Muslim, with all the stereotypical notions attached to that, but also a freedom-loving artist and a humorist.

I'm not just the butt of jokes, but a purveyor of them -- a non-violent wielder of the pen, which I maintain is funnier than the sword.

I'm no stranger to controversy and censorship, and I've received my fair share of death threats over the years. So I've had ample opportunity to mull the thorny question of freedom of expression versus responsibility.

Was Charlie Hebdo, the satirical publication whose staffers were murdered by Islamic extremists in Paris, always the fairest and most responsible newspaper in the world? Of course not. I confess to have often cringed at its apparent double-standard when it comes to skewering Muslims and Jews.

But does anyone -- ever -- deserve to be harassed, hounded, or murdered for expressing an opinion, however egregious it may be perceived by some?

Voltaire's biographer Evelyn Beatrice Hall eloquently and definitively answered that question long ago: "I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it."

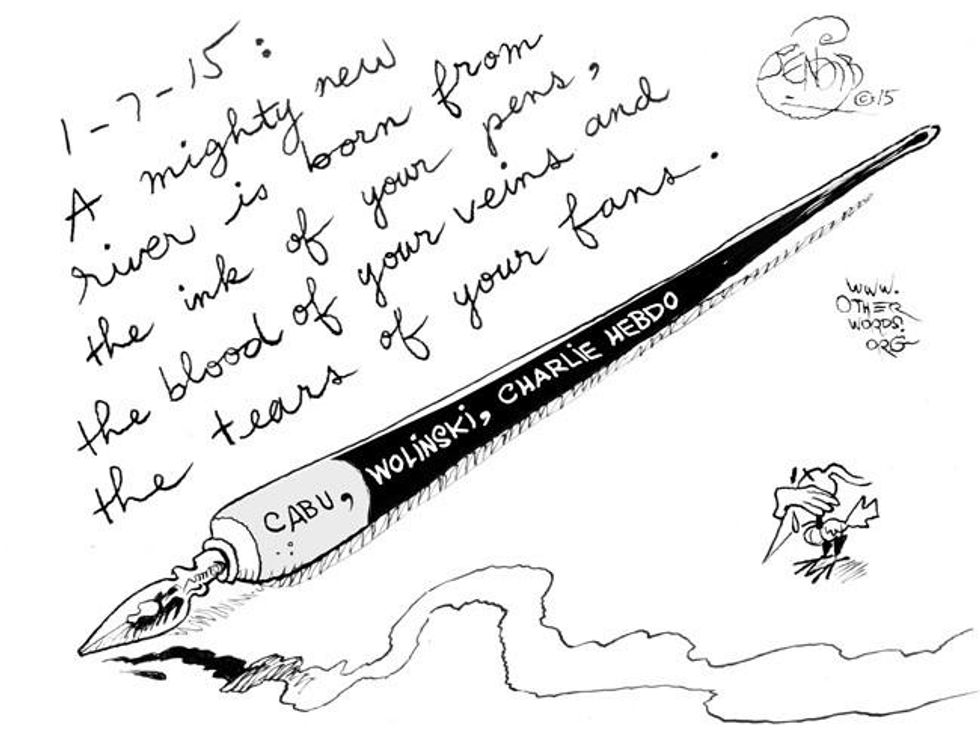

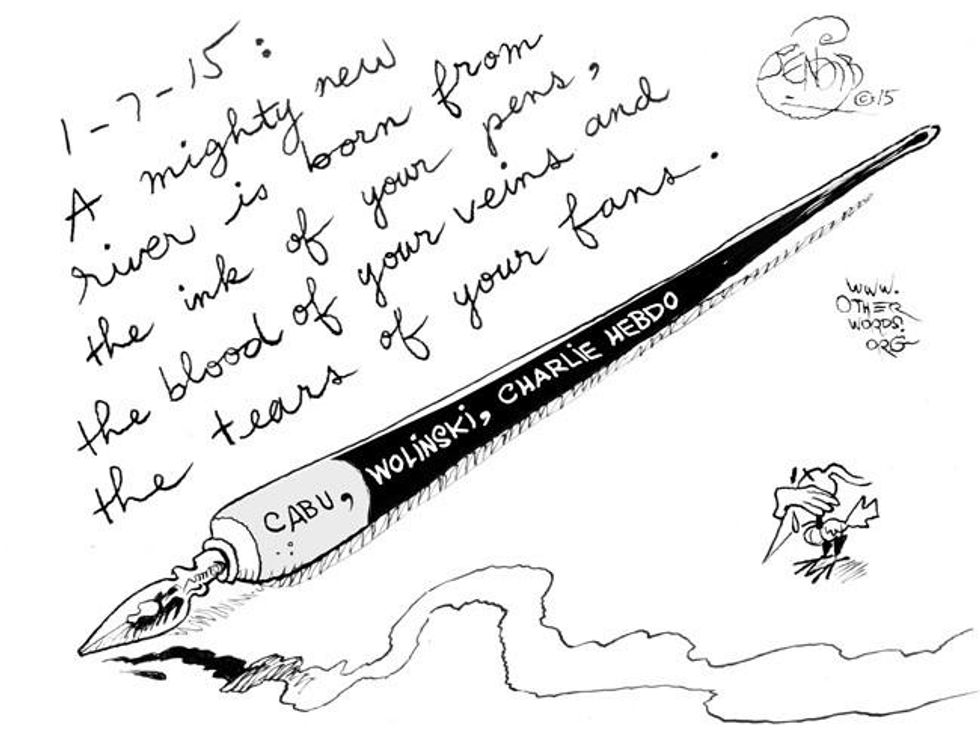

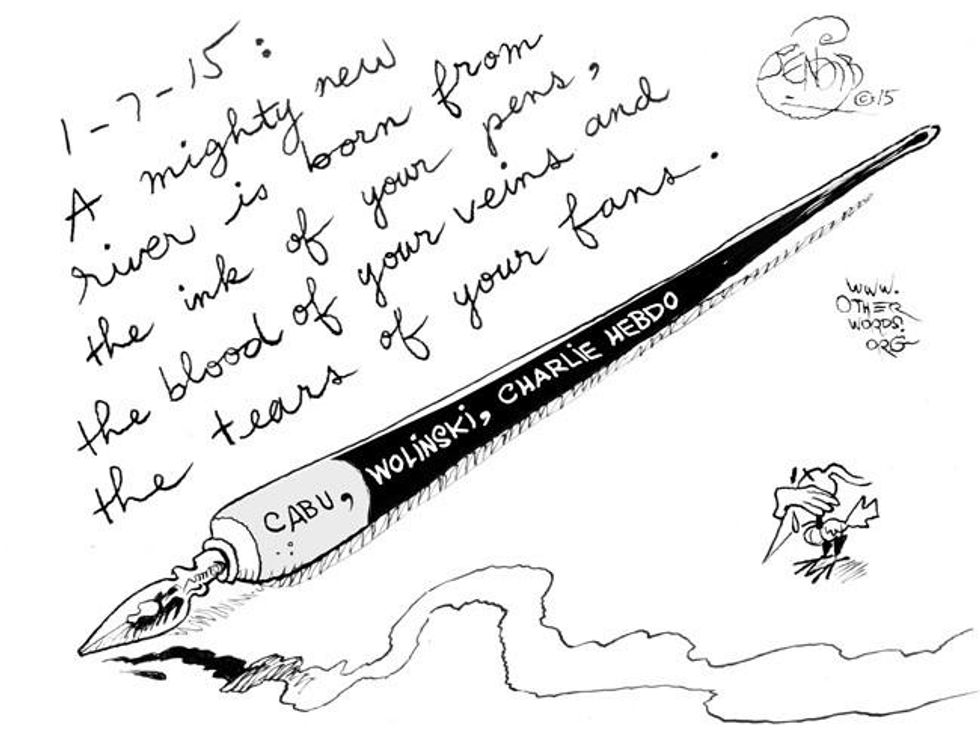

Personally, I will always remember January 7 as a day of infamy, a catastrophe delivering layer upon layer of misery.

As a human being, I feel disgust over the murder of 12 innocent people.

As an artist, I feel a profound sense of grief over the loss of four fellow cartoonists -- including the great Cabu (also known as Jean Cabut), who inspired me as a young man to become a cartoonist.

And as a member of the worldwide Muslim community, I'm plagued with a nagging sense of shame and fear of the inevitable backlash that will follow in an already Islamophobic Europe, where most of my family still resides.

I worry that the unspeakable acts of a few will drown out the sincere protestations of the many that this kind of horror doesn't speak in our name.

Former French justice minister Robert Badinter -- no particular friend of the Muslim community -- has warned his fellow citizens not to fall into the extremist trap of letting barbaric violence divide French society, of which nearly 10 percent is Muslim. But tensions are running high.

Yet beyond the social polarization -- manifested by both senseless Islamist violence and the cheap Islamophobia of opportunistic politicians and media -- lies a more interesting and nuanced reality: signs of hope and progress.

Long before this attack, French people were showing what it means to coexist in a multi-ethnic and pluralistic society.

Among the many good works he will be remembered for, cartoonist Georges Wolinski -- who was among the cartoonists assassinated in cold blood in the name of wounded religious pride -- once came to the rescue of Menouar Merabtene, the Algerian cartoonist best known as Slim, a close friend of mine who was fleeing from persecution in his native country.

Throughout the 1990s, a bloody civil war raged between Islamist militants and the autocratic Algerian government. Many artists and intellectuals opposed to the Islamist agenda were systematically assassinated in that conflict.

Out of simple human solidarity, Wolinski -- a Jewish cartoonist from France -- spontaneously intervened to secure a job for the beleaguered Muslim-Algerian Slim at the Paris newspaper L'Humanite.

Similarly, thousands of French people are mourning and praising slain Muslim police officer Ahmed Merabet. He died pursuing men suspected of perpetrating the Charlie Hebdo massacre.

Like the stories of North African Muslims standing in solidarity with their Jewish brethren against the Vichy government's hunt for North African Jews during World War II, these simple stories tend to get lost in the din of terrorist mayhem.

But in the end, bullets and bombs can never silence the voices of laughter and friendship.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

As a political cartoonist who happens to be both American and Muslim, I often find myself at the intersection of media curiosity: Muslim, with all the stereotypical notions attached to that, but also a freedom-loving artist and a humorist.

I'm not just the butt of jokes, but a purveyor of them -- a non-violent wielder of the pen, which I maintain is funnier than the sword.

I'm no stranger to controversy and censorship, and I've received my fair share of death threats over the years. So I've had ample opportunity to mull the thorny question of freedom of expression versus responsibility.

Was Charlie Hebdo, the satirical publication whose staffers were murdered by Islamic extremists in Paris, always the fairest and most responsible newspaper in the world? Of course not. I confess to have often cringed at its apparent double-standard when it comes to skewering Muslims and Jews.

But does anyone -- ever -- deserve to be harassed, hounded, or murdered for expressing an opinion, however egregious it may be perceived by some?

Voltaire's biographer Evelyn Beatrice Hall eloquently and definitively answered that question long ago: "I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it."

Personally, I will always remember January 7 as a day of infamy, a catastrophe delivering layer upon layer of misery.

As a human being, I feel disgust over the murder of 12 innocent people.

As an artist, I feel a profound sense of grief over the loss of four fellow cartoonists -- including the great Cabu (also known as Jean Cabut), who inspired me as a young man to become a cartoonist.

And as a member of the worldwide Muslim community, I'm plagued with a nagging sense of shame and fear of the inevitable backlash that will follow in an already Islamophobic Europe, where most of my family still resides.

I worry that the unspeakable acts of a few will drown out the sincere protestations of the many that this kind of horror doesn't speak in our name.

Former French justice minister Robert Badinter -- no particular friend of the Muslim community -- has warned his fellow citizens not to fall into the extremist trap of letting barbaric violence divide French society, of which nearly 10 percent is Muslim. But tensions are running high.

Yet beyond the social polarization -- manifested by both senseless Islamist violence and the cheap Islamophobia of opportunistic politicians and media -- lies a more interesting and nuanced reality: signs of hope and progress.

Long before this attack, French people were showing what it means to coexist in a multi-ethnic and pluralistic society.

Among the many good works he will be remembered for, cartoonist Georges Wolinski -- who was among the cartoonists assassinated in cold blood in the name of wounded religious pride -- once came to the rescue of Menouar Merabtene, the Algerian cartoonist best known as Slim, a close friend of mine who was fleeing from persecution in his native country.

Throughout the 1990s, a bloody civil war raged between Islamist militants and the autocratic Algerian government. Many artists and intellectuals opposed to the Islamist agenda were systematically assassinated in that conflict.

Out of simple human solidarity, Wolinski -- a Jewish cartoonist from France -- spontaneously intervened to secure a job for the beleaguered Muslim-Algerian Slim at the Paris newspaper L'Humanite.

Similarly, thousands of French people are mourning and praising slain Muslim police officer Ahmed Merabet. He died pursuing men suspected of perpetrating the Charlie Hebdo massacre.

Like the stories of North African Muslims standing in solidarity with their Jewish brethren against the Vichy government's hunt for North African Jews during World War II, these simple stories tend to get lost in the din of terrorist mayhem.

But in the end, bullets and bombs can never silence the voices of laughter and friendship.

As a political cartoonist who happens to be both American and Muslim, I often find myself at the intersection of media curiosity: Muslim, with all the stereotypical notions attached to that, but also a freedom-loving artist and a humorist.

I'm not just the butt of jokes, but a purveyor of them -- a non-violent wielder of the pen, which I maintain is funnier than the sword.

I'm no stranger to controversy and censorship, and I've received my fair share of death threats over the years. So I've had ample opportunity to mull the thorny question of freedom of expression versus responsibility.

Was Charlie Hebdo, the satirical publication whose staffers were murdered by Islamic extremists in Paris, always the fairest and most responsible newspaper in the world? Of course not. I confess to have often cringed at its apparent double-standard when it comes to skewering Muslims and Jews.

But does anyone -- ever -- deserve to be harassed, hounded, or murdered for expressing an opinion, however egregious it may be perceived by some?

Voltaire's biographer Evelyn Beatrice Hall eloquently and definitively answered that question long ago: "I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it."

Personally, I will always remember January 7 as a day of infamy, a catastrophe delivering layer upon layer of misery.

As a human being, I feel disgust over the murder of 12 innocent people.

As an artist, I feel a profound sense of grief over the loss of four fellow cartoonists -- including the great Cabu (also known as Jean Cabut), who inspired me as a young man to become a cartoonist.

And as a member of the worldwide Muslim community, I'm plagued with a nagging sense of shame and fear of the inevitable backlash that will follow in an already Islamophobic Europe, where most of my family still resides.

I worry that the unspeakable acts of a few will drown out the sincere protestations of the many that this kind of horror doesn't speak in our name.

Former French justice minister Robert Badinter -- no particular friend of the Muslim community -- has warned his fellow citizens not to fall into the extremist trap of letting barbaric violence divide French society, of which nearly 10 percent is Muslim. But tensions are running high.

Yet beyond the social polarization -- manifested by both senseless Islamist violence and the cheap Islamophobia of opportunistic politicians and media -- lies a more interesting and nuanced reality: signs of hope and progress.

Long before this attack, French people were showing what it means to coexist in a multi-ethnic and pluralistic society.

Among the many good works he will be remembered for, cartoonist Georges Wolinski -- who was among the cartoonists assassinated in cold blood in the name of wounded religious pride -- once came to the rescue of Menouar Merabtene, the Algerian cartoonist best known as Slim, a close friend of mine who was fleeing from persecution in his native country.

Throughout the 1990s, a bloody civil war raged between Islamist militants and the autocratic Algerian government. Many artists and intellectuals opposed to the Islamist agenda were systematically assassinated in that conflict.

Out of simple human solidarity, Wolinski -- a Jewish cartoonist from France -- spontaneously intervened to secure a job for the beleaguered Muslim-Algerian Slim at the Paris newspaper L'Humanite.

Similarly, thousands of French people are mourning and praising slain Muslim police officer Ahmed Merabet. He died pursuing men suspected of perpetrating the Charlie Hebdo massacre.

Like the stories of North African Muslims standing in solidarity with their Jewish brethren against the Vichy government's hunt for North African Jews during World War II, these simple stories tend to get lost in the din of terrorist mayhem.

But in the end, bullets and bombs can never silence the voices of laughter and friendship.