SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

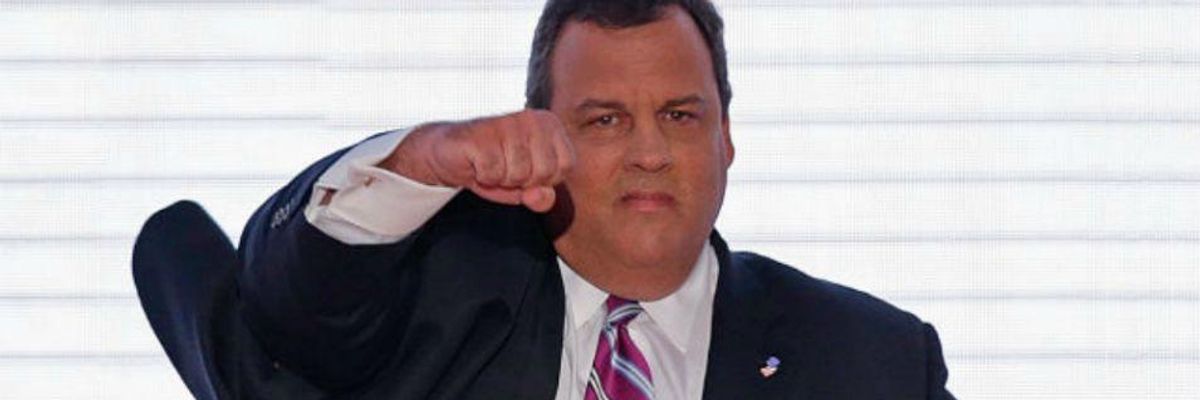

That Gov. Chris Christie said an outrageous and offensive thing about teachers is not surprising. The disappointing thing, writes Bryant, "was how tepid the response has been from anyone but members of the teachers' unions themselves."

What was the most surprising thing about New Jersey Governor and Republican presidential candidate Chris Christie's recent remark that the "national teachers union" deserves a "punch in the face?"

What was the most surprising thing about New Jersey Governor and Republican presidential candidate Chris Christie's recent remark that the "national teachers union" deserves a "punch in the face?"

Certainly not that he made the remark. As multiple news outlets reporting on the comment note, Christie "has had several public confrontations with individual teachers."

No, what was most surprising was how tepid the response has been from anyone but members of the teachers' unions themselves.

In contrast to the "firestorm," according to The Washington Post, that Jeb Bush, also a Republican presidential candidate, ignited after he said he was "not sure we need half a billion dollars for women's health issues," Christie's remark doesn't appear to have received a strong rebuke from prominent commentators or representatives of the Democratic Party. Although Bush's comment has been called a "gaffe" by Beltway pundits, Christie's comment has not been similarly labeled.

In fact, the editorial board of The Wall Street Journal said Christie's insult is proof of "the growing consensus that teachers unions are the main obstacle to improvement in American public schools."

What motivated Christie to make the remark, as an Education Week reporter surmised, was a need to get "an upper hand in a crowded GOP presidential election field."

If that supposition is true, Christie likely failed. There is nothing unique about Republican candidates attacking public school teachers.

As education journalist Valerie Strauss points out on her blog at The Washington Post, Christie "is hardly the only candidate antagonistic toward teachers and their unions." Strauss explains that at least three other Republican presidential candidates - Bush and Governors Scott Walker of Wisconsin and John Kasich of Ohio - have been more "damaging" to teachers and their unions.

There are also a number of political leaders in the Democratic Party who have histories of making unkind remarks about teachers in public. Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel has often been accused of being "insulting" to educators in his high-handed governance of the city's public schools. New York Governor Andrew Cuomo has also been accused of waging "attacks" on public school educators.

So political candidates of all stripes seem to have very few inhibitions to attack public schools teachers - or inclinations to defend them when they are viciously singled out.

There are reasons for this tendency that go beyond political gamesmanship. Certainly politicians want teachers to vote for them and give them campaign contributions. And when weighing that benefit against the potential votes and money that could come in from people who resent being taxed to pay for teacher salaries and benefits, there will always be politicians who opt to go for the anti-tax message.

But the antipathy, or apathy, many politicians tend to have toward teachers derives from the reality that politicians tend to have unreal expectations about teachers and what they do.

Teachers And Their Unions

But first, let's be clear that an attack on teachers' unions, like the one Christie's remark exemplified, is an attack on teachers, or at least a very large representation of them.

If you don't agree with that, then you've simply never been to a teachers' union meeting of any kind. If you ever make it to a national assembly of one of these organizations, what you'll confront in the convention hall is a massive showing of literally hundreds and hundreds of teachers. Seriously, if teachers' unions aren't made up of teachers, who on earth are they made of?

Teachers take any attack on their unions as something personal. As at least one teacher wrote on his personal blog, Christie's remark strikes at teachers personally: "Christie wants to punch me in the face ... After all, I am a public school teacher. I do belong to one of those nefarious teachers unions."

Now does that mean that teachers' unions always represent the majority of their members? Of course not. Can any representative body claim that?

But teachers' unions are, well, teachers, and political leaders who openly disrespect these organizations are in essence disrespecting teachers. Why do politicians so often disrespect teachers?

The Teacher Wars

Dana Goldstein in her tremendous book The Teacher Wars: A History of America's Most Embattled Profession plunges into that question with great depth and insight this short piece of writing won't attempt to summarize.

In her detailed account of the complex history of the teaching profession in America, Goldstein grapples with understanding why, in her words, "powerful people seemed to feel indignant about the incompetence and job security of public school teachers."

Goldstein vividly describes the current regard political leaders have for teachers as a "confusing dichotomy" in which teachers are worshipped in the abstract and ridiculed when they, in the flesh, publically represent their needs and interests. She likens the current obsession with education "reform" to a "moral panic" that by and large has "nothing to do" with the quality of teachers' work. And she draws on copious evidence from the historical record to today's news accounts to illustrate how public school administrators working with their local teachers' unions have developed successful education policies that serve both the interests of teachers and the taxpayers' needs to know their money is being well spent.

Goldstein's remarkably nuanced narrative culminates with a brief "lessons from history" that should guide politicians in how they talk about teachers, including the importance of their salaries, their needs for collaborative space and time, and the undue expectations being put on teachers, and the education system as a whole.

But politicians don't do nuance.

"Results" Teachers Can't Give

What politician do, mostly, is speak in the language of "results." And in today's economically minded culture, results are framed in the language of business.

Teaching, we're so often told, "produces learning" like a sausage machine spits out pods of ground meat wrapped in pig gut. When it comes time for politicians to prove their worthiness to the public, they assume it's the teachers' job to show an increase in some sort of measurable output, such as a rise in standardized test scores or a positive swing in graduation rates. When those magic numbers aren't available, there's hell to pay, and teachers have to be made "accountable" - never mind that the financial support for education programs is less than it was seven years ago, more students are plagued with the trauma of poverty, teacher salaries are not equivalent to what other professionals make, and higher stress levels in schools have caused teacher morale to plummet.

However, it has never been, and never will be, teachers' jobs to "produce" learning. Students are the ones who do the learning. And "learning isn't even a "product."

As retired teacher and popular blogger Walt Gardner explains for Education Week, teaching isn't about production as much as it is about relationships. "Teaching by its very nature is a person-to-person undertaking," he writes. "The trouble is that everything going on today undermines the teacher-student relationship ... What good does it do to teach a subject well (high standardized test scores) but to teach students to hate the subject in the process?"

What politicians don't get is that teachers will generally put up with all the negative conditions of too little money to do a complicated, stress-filled job if people who hold public office would show at least a clue they get this.

Very few politicians do, so their short term interests rarely align with the perspectives of teachers whose very jobs demand they think long term and developmentally. Until one of those two parties adjusts their attitudes, we'll continue to see teachers openly disparaged, or disregarded, in the public sphere. For the sake of our children, let's hope the politicians are the ones who make the adjustment.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

What was the most surprising thing about New Jersey Governor and Republican presidential candidate Chris Christie's recent remark that the "national teachers union" deserves a "punch in the face?"

Certainly not that he made the remark. As multiple news outlets reporting on the comment note, Christie "has had several public confrontations with individual teachers."

No, what was most surprising was how tepid the response has been from anyone but members of the teachers' unions themselves.

In contrast to the "firestorm," according to The Washington Post, that Jeb Bush, also a Republican presidential candidate, ignited after he said he was "not sure we need half a billion dollars for women's health issues," Christie's remark doesn't appear to have received a strong rebuke from prominent commentators or representatives of the Democratic Party. Although Bush's comment has been called a "gaffe" by Beltway pundits, Christie's comment has not been similarly labeled.

In fact, the editorial board of The Wall Street Journal said Christie's insult is proof of "the growing consensus that teachers unions are the main obstacle to improvement in American public schools."

What motivated Christie to make the remark, as an Education Week reporter surmised, was a need to get "an upper hand in a crowded GOP presidential election field."

If that supposition is true, Christie likely failed. There is nothing unique about Republican candidates attacking public school teachers.

As education journalist Valerie Strauss points out on her blog at The Washington Post, Christie "is hardly the only candidate antagonistic toward teachers and their unions." Strauss explains that at least three other Republican presidential candidates - Bush and Governors Scott Walker of Wisconsin and John Kasich of Ohio - have been more "damaging" to teachers and their unions.

There are also a number of political leaders in the Democratic Party who have histories of making unkind remarks about teachers in public. Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel has often been accused of being "insulting" to educators in his high-handed governance of the city's public schools. New York Governor Andrew Cuomo has also been accused of waging "attacks" on public school educators.

So political candidates of all stripes seem to have very few inhibitions to attack public schools teachers - or inclinations to defend them when they are viciously singled out.

There are reasons for this tendency that go beyond political gamesmanship. Certainly politicians want teachers to vote for them and give them campaign contributions. And when weighing that benefit against the potential votes and money that could come in from people who resent being taxed to pay for teacher salaries and benefits, there will always be politicians who opt to go for the anti-tax message.

But the antipathy, or apathy, many politicians tend to have toward teachers derives from the reality that politicians tend to have unreal expectations about teachers and what they do.

Teachers And Their Unions

But first, let's be clear that an attack on teachers' unions, like the one Christie's remark exemplified, is an attack on teachers, or at least a very large representation of them.

If you don't agree with that, then you've simply never been to a teachers' union meeting of any kind. If you ever make it to a national assembly of one of these organizations, what you'll confront in the convention hall is a massive showing of literally hundreds and hundreds of teachers. Seriously, if teachers' unions aren't made up of teachers, who on earth are they made of?

Teachers take any attack on their unions as something personal. As at least one teacher wrote on his personal blog, Christie's remark strikes at teachers personally: "Christie wants to punch me in the face ... After all, I am a public school teacher. I do belong to one of those nefarious teachers unions."

Now does that mean that teachers' unions always represent the majority of their members? Of course not. Can any representative body claim that?

But teachers' unions are, well, teachers, and political leaders who openly disrespect these organizations are in essence disrespecting teachers. Why do politicians so often disrespect teachers?

The Teacher Wars

Dana Goldstein in her tremendous book The Teacher Wars: A History of America's Most Embattled Profession plunges into that question with great depth and insight this short piece of writing won't attempt to summarize.

In her detailed account of the complex history of the teaching profession in America, Goldstein grapples with understanding why, in her words, "powerful people seemed to feel indignant about the incompetence and job security of public school teachers."

Goldstein vividly describes the current regard political leaders have for teachers as a "confusing dichotomy" in which teachers are worshipped in the abstract and ridiculed when they, in the flesh, publically represent their needs and interests. She likens the current obsession with education "reform" to a "moral panic" that by and large has "nothing to do" with the quality of teachers' work. And she draws on copious evidence from the historical record to today's news accounts to illustrate how public school administrators working with their local teachers' unions have developed successful education policies that serve both the interests of teachers and the taxpayers' needs to know their money is being well spent.

Goldstein's remarkably nuanced narrative culminates with a brief "lessons from history" that should guide politicians in how they talk about teachers, including the importance of their salaries, their needs for collaborative space and time, and the undue expectations being put on teachers, and the education system as a whole.

But politicians don't do nuance.

"Results" Teachers Can't Give

What politician do, mostly, is speak in the language of "results." And in today's economically minded culture, results are framed in the language of business.

Teaching, we're so often told, "produces learning" like a sausage machine spits out pods of ground meat wrapped in pig gut. When it comes time for politicians to prove their worthiness to the public, they assume it's the teachers' job to show an increase in some sort of measurable output, such as a rise in standardized test scores or a positive swing in graduation rates. When those magic numbers aren't available, there's hell to pay, and teachers have to be made "accountable" - never mind that the financial support for education programs is less than it was seven years ago, more students are plagued with the trauma of poverty, teacher salaries are not equivalent to what other professionals make, and higher stress levels in schools have caused teacher morale to plummet.

However, it has never been, and never will be, teachers' jobs to "produce" learning. Students are the ones who do the learning. And "learning isn't even a "product."

As retired teacher and popular blogger Walt Gardner explains for Education Week, teaching isn't about production as much as it is about relationships. "Teaching by its very nature is a person-to-person undertaking," he writes. "The trouble is that everything going on today undermines the teacher-student relationship ... What good does it do to teach a subject well (high standardized test scores) but to teach students to hate the subject in the process?"

What politicians don't get is that teachers will generally put up with all the negative conditions of too little money to do a complicated, stress-filled job if people who hold public office would show at least a clue they get this.

Very few politicians do, so their short term interests rarely align with the perspectives of teachers whose very jobs demand they think long term and developmentally. Until one of those two parties adjusts their attitudes, we'll continue to see teachers openly disparaged, or disregarded, in the public sphere. For the sake of our children, let's hope the politicians are the ones who make the adjustment.

What was the most surprising thing about New Jersey Governor and Republican presidential candidate Chris Christie's recent remark that the "national teachers union" deserves a "punch in the face?"

Certainly not that he made the remark. As multiple news outlets reporting on the comment note, Christie "has had several public confrontations with individual teachers."

No, what was most surprising was how tepid the response has been from anyone but members of the teachers' unions themselves.

In contrast to the "firestorm," according to The Washington Post, that Jeb Bush, also a Republican presidential candidate, ignited after he said he was "not sure we need half a billion dollars for women's health issues," Christie's remark doesn't appear to have received a strong rebuke from prominent commentators or representatives of the Democratic Party. Although Bush's comment has been called a "gaffe" by Beltway pundits, Christie's comment has not been similarly labeled.

In fact, the editorial board of The Wall Street Journal said Christie's insult is proof of "the growing consensus that teachers unions are the main obstacle to improvement in American public schools."

What motivated Christie to make the remark, as an Education Week reporter surmised, was a need to get "an upper hand in a crowded GOP presidential election field."

If that supposition is true, Christie likely failed. There is nothing unique about Republican candidates attacking public school teachers.

As education journalist Valerie Strauss points out on her blog at The Washington Post, Christie "is hardly the only candidate antagonistic toward teachers and their unions." Strauss explains that at least three other Republican presidential candidates - Bush and Governors Scott Walker of Wisconsin and John Kasich of Ohio - have been more "damaging" to teachers and their unions.

There are also a number of political leaders in the Democratic Party who have histories of making unkind remarks about teachers in public. Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel has often been accused of being "insulting" to educators in his high-handed governance of the city's public schools. New York Governor Andrew Cuomo has also been accused of waging "attacks" on public school educators.

So political candidates of all stripes seem to have very few inhibitions to attack public schools teachers - or inclinations to defend them when they are viciously singled out.

There are reasons for this tendency that go beyond political gamesmanship. Certainly politicians want teachers to vote for them and give them campaign contributions. And when weighing that benefit against the potential votes and money that could come in from people who resent being taxed to pay for teacher salaries and benefits, there will always be politicians who opt to go for the anti-tax message.

But the antipathy, or apathy, many politicians tend to have toward teachers derives from the reality that politicians tend to have unreal expectations about teachers and what they do.

Teachers And Their Unions

But first, let's be clear that an attack on teachers' unions, like the one Christie's remark exemplified, is an attack on teachers, or at least a very large representation of them.

If you don't agree with that, then you've simply never been to a teachers' union meeting of any kind. If you ever make it to a national assembly of one of these organizations, what you'll confront in the convention hall is a massive showing of literally hundreds and hundreds of teachers. Seriously, if teachers' unions aren't made up of teachers, who on earth are they made of?

Teachers take any attack on their unions as something personal. As at least one teacher wrote on his personal blog, Christie's remark strikes at teachers personally: "Christie wants to punch me in the face ... After all, I am a public school teacher. I do belong to one of those nefarious teachers unions."

Now does that mean that teachers' unions always represent the majority of their members? Of course not. Can any representative body claim that?

But teachers' unions are, well, teachers, and political leaders who openly disrespect these organizations are in essence disrespecting teachers. Why do politicians so often disrespect teachers?

The Teacher Wars

Dana Goldstein in her tremendous book The Teacher Wars: A History of America's Most Embattled Profession plunges into that question with great depth and insight this short piece of writing won't attempt to summarize.

In her detailed account of the complex history of the teaching profession in America, Goldstein grapples with understanding why, in her words, "powerful people seemed to feel indignant about the incompetence and job security of public school teachers."

Goldstein vividly describes the current regard political leaders have for teachers as a "confusing dichotomy" in which teachers are worshipped in the abstract and ridiculed when they, in the flesh, publically represent their needs and interests. She likens the current obsession with education "reform" to a "moral panic" that by and large has "nothing to do" with the quality of teachers' work. And she draws on copious evidence from the historical record to today's news accounts to illustrate how public school administrators working with their local teachers' unions have developed successful education policies that serve both the interests of teachers and the taxpayers' needs to know their money is being well spent.

Goldstein's remarkably nuanced narrative culminates with a brief "lessons from history" that should guide politicians in how they talk about teachers, including the importance of their salaries, their needs for collaborative space and time, and the undue expectations being put on teachers, and the education system as a whole.

But politicians don't do nuance.

"Results" Teachers Can't Give

What politician do, mostly, is speak in the language of "results." And in today's economically minded culture, results are framed in the language of business.

Teaching, we're so often told, "produces learning" like a sausage machine spits out pods of ground meat wrapped in pig gut. When it comes time for politicians to prove their worthiness to the public, they assume it's the teachers' job to show an increase in some sort of measurable output, such as a rise in standardized test scores or a positive swing in graduation rates. When those magic numbers aren't available, there's hell to pay, and teachers have to be made "accountable" - never mind that the financial support for education programs is less than it was seven years ago, more students are plagued with the trauma of poverty, teacher salaries are not equivalent to what other professionals make, and higher stress levels in schools have caused teacher morale to plummet.

However, it has never been, and never will be, teachers' jobs to "produce" learning. Students are the ones who do the learning. And "learning isn't even a "product."

As retired teacher and popular blogger Walt Gardner explains for Education Week, teaching isn't about production as much as it is about relationships. "Teaching by its very nature is a person-to-person undertaking," he writes. "The trouble is that everything going on today undermines the teacher-student relationship ... What good does it do to teach a subject well (high standardized test scores) but to teach students to hate the subject in the process?"

What politicians don't get is that teachers will generally put up with all the negative conditions of too little money to do a complicated, stress-filled job if people who hold public office would show at least a clue they get this.

Very few politicians do, so their short term interests rarely align with the perspectives of teachers whose very jobs demand they think long term and developmentally. Until one of those two parties adjusts their attitudes, we'll continue to see teachers openly disparaged, or disregarded, in the public sphere. For the sake of our children, let's hope the politicians are the ones who make the adjustment.