Remembering Katrina in the #BlackLivesMatter Movement

In the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, 80 percent of New Orleans was under water, thousands of people were displaced, and at least 1,800 people were killed. The country watched in disbelief as residents -- a disproportionate number of whom were black -- pleaded for help on rooftops as then-President George W.

In the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, 80 percent of New Orleans was under water, thousands of people were displaced, and at least 1,800 people were killed. The country watched in disbelief as residents -- a disproportionate number of whom were black -- pleaded for help on rooftops as then-President George W. Bush watched from afar -- first from Washington, D.C., then overhead from a helicopter. All the while, the city's poorest community, the Lower Ninth Ward, had up to 12 feet of water sitting stagnant in some areas for weeks. It was the last place to have power and water service restored, and the last to have the flood waters pumped out.

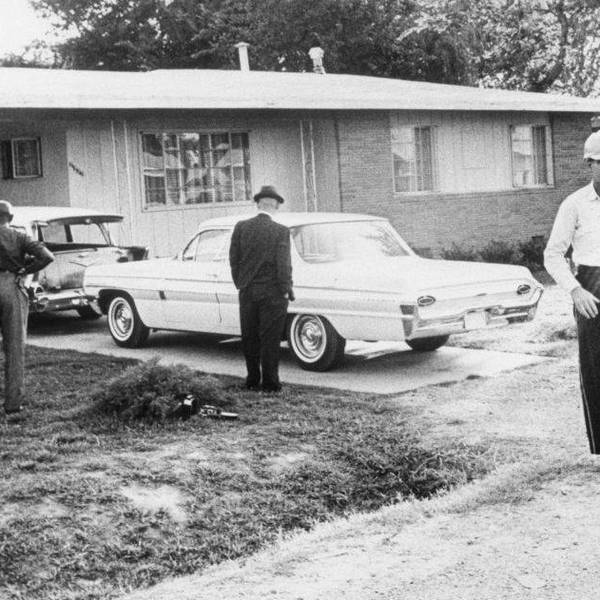

Despite the dire circumstances, news outlets and law enforcement quickly began to label the black residents as "looters." They were not viewed as people trying to survive, but rather as criminals who needed to be reined in. New Orleans Police Department Captain James Scott instructed police officers that they had the "authority by martial law to shoot looters."

And that's what they did: All told, 11 people were shot by law enforcement officials following the storm. The most well-known incident occurred six days after Katrina hit, when members of the NOPD -- unprovoked and armed with assault rifles -- stormed the Danziger Bridge and began firing on a group of unarmed civilians in search of food. Two people were killed, including a mentally disabled man who was shot in the back and a 19-year-old high school student. Four more were seriously injured, including three members of the Bartholomew family. Leonard Bartholomew suffered a gunshot wound to the head, his daughter was wounded in the abdomen, and his wife Susan lost an arm due to the severity of the gun blast that hit her. Five officers were arrested and convicted. Ten years later, the Bartholomew family's civil suit remains unsettled.

The feeling that black lives did not matter was most famously summed up by rapper Kanye West when he stated firmly during a primetime telethon that "George Bush doesn't care about Black people."

As Hurricane Katrina revealed, the consequences of poverty, segregation, police brutality, and environmental racism coming to a head have tragic results.

Amidst the growing threat of climate change, this perfect storm must not be forgotten. While an extreme weather event, such as a flood, heat wave, or hurricane may seem like an equal opportunity force of destruction, in reality these events exacerbate the underlying injustices that exist in our communities year round. Understanding just how vulnerable low-income, black communities are to these threats is critical to protecting black lives in the 21st century.

Today, much of New Orleans is back to normal, with more than half of the city's neighborhoods reaching their pre-storm population levels. However, that's far from the case for the infamous Lower Ninth Ward. In the years following Katrina, only about 37 percent of households have returned home. Black residents who wanted to rebuild simply couldn't afford to as federal aid was allocated based on home values rather than the cost of construction. The average gap between the damage accrued and the grants awarded to residents of the Lower Ninth Ward was $75,000, more than twice the average household income of the residents there.

As Professor Beverly Wright of Loyola University New Orleans explained, "pre-storm vulnerabilities continue to limit the participation of thousands of disadvantaged individuals and communities in the after-storm reconstruction, rebuilding, and recovery. In these communities, days of hurt and loss have become years of grief, dislocation, and displacement."

As Hurricane Katrina revealed, the consequences of poverty, segregation, police brutality, and environmental racism coming to a head have tragic results.

Hurricane Katrina exposed that even in our hour of greatest need, black people are often not afforded the tragic gift of vulnerability. Instead, we are an ever present threat.

Today's #BlackLivesMatter movement -- a national call to action and response against "extrajudicial killings of Black people by police and vigilantes" -- is focused on just that. The movement demands accountability of law enforcement, while affirming the need to invest in low-income, black communities "in order to create jobs, housing and schools." It is this last demand that is often left out of media discussions of the movement, but is critical to the health, wealth, and well-being of African American families.

The legacy of segregation and disinvestment

While the United States is known as the "land of opportunity" the world over, a more accurate description is that the U.S. is composed of disparate lands of opportunity. Earlier this year, Harvard economist Raj Chetty, along with his colleagues, released two studies that add to the growing body of research that your zip code determines your life chances.

Orleans Parish in Louisiana -- where New Orleans is located -- is among the worst counties in the U.S. for children in poor families, according to Chetty's findings. A child born in this part of Louisiana makes approximately 19 percent less when she turns 26 than if her family moved to an average place when she was a small child. This is the story of many communities across the country, as concentrated poverty persists and low-income communities and communities of color face inferior housing, poor air quality, failing schools, inadequate public infrastructure, and few employment opportunities. Black families live in these communities at disproportionate numbers and, as past policies reveal, this was by design.

For decades, the federal government invested in the stability of affluent, predominantly white communities, while giving localities the authority to neglect low-income communities and communities of color. Such practices included everything from redlining, beginning in the 1930s, where banks were allowed to exclude African American communities from receiving home loans, to the expansion of the highway system, which rammed through and destroyed African American businesses and homes in the process.

Today, the average African American family making $100,000 a year lives in a more disadvantaged neighborhood -- characterized by racial segregation, high rates of poverty and unemployment, and exposure to neighborhood violence -- than the average white family making $30,000 a year, revealing how past social policies continue to affect neighborhood choice. It is this lack of choice that is putting black lives at risk and, in some instances, directly in the path of extreme weather events.

Vulnerability to extreme weather

On October 29, 2012, Superstorm Sandy hit the northeastern United States and became the second costliest storm in U.S. history after Katrina. Heeding the lessons from the blundered response in New Orleans, the federal government was quick to act with Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) officials arriving throughout the region and President Barack Obama surveying the damage from the ground.

Despite the quick response, the region suffered greatly, with low-income people and people of color shouldering a disproportionate share of the damage and chaos. In New York City, many low-income, elderly, and disabled residents were stranded in public housing towers for weeks after the storm due to elevator outages. Other residents remained in the high rises, despite having no heat or power, because they had nowhere else to go. The storm served as a reminder of just how vulnerable low-income, communities of color are to such disasters.

Given the enduring legacy of discrimination and segregation in the United States, it is not surprising that millions of black families are forced to live in neighborhoods that are accessible to them precisely because these neighborhoods are at greatest risk.

On top of living in poor quality housing stock, which is older and more susceptible to damage, black households disproportionately live near industrial sites like chemical plants and refineries, which can cause toxic spills during storms. Furthermore, due to a greater likelihood of living in close proximity to waste facilities, people of color are disproportionately impacted by storm debris removal in the aftermath of extreme weather events.

Given the enduring legacy of discrimination and segregation in the United States, it is not surprising that millions of black families are forced to live in neighborhoods that are accessible to them precisely because these neighborhoods are at greatest risk.

And with the black unemployment rate more than twice the rate among whites, black households have a harder time bouncing back after disasters. This is particularly the case for non-salaried workers, who, as Ross Eisenbrey, vice president of the Economic Policy Institute, explains are at the mercy of their employers: "If the business closes because of the storm, employers don't have to pay non-salaried workers for lost wages. And if the business is open, but the worker can't make it into work, employers are also not required to pay for lost wages."

Building resilient communities

While much of the nation was outraged at Bush's failed response to Katrina, we should remain similarly outraged at the risks black communities continue to endure year round. Last year alone, the United States experienced eight severe weather, flood, and drought events, causing $19 billion in damages across 35 states, and cost us 65 human lives. Each year, extreme heat -- one of the leading weather-related killers in the U.S. -- results in hundreds of fatalities, particularly in inner-city neighborhoods that tend to be several degrees hotter than other communities due to the presence of fewer trees and more asphalt.

Climate change has become an ever-present Katrina.

Earlier this month, President Obama reaffirmed his commitment to cutting carbon pollution -- the leading contributor to climate disruption caused by human activities -- by announcing the most significant action that any American president has made to address the very real threat of climate change. At the same time, a new poll by The Washington Post revealed that 60 percent of Americans believe the county must continue making changes to give blacks and whites equal rights, compared to just 46 percent last year. We're at a unique juncture in our nation's history where the public increasingly recognizes that once seemingly intractable problems are our responsibility.

While the Obama administration has taken great steps to ensure our nation's communities are more resilient in the face of climate-fueled extreme weather, the outsized consequences of these events on poor, black communities requires special attention. It requires the backing of a movement. It requires that in every policy debate, we constantly affirm that black lives matter.

We cannot ignore our nation's housing crisis, the environmental justice issues that plague our communities, and the growing economic inequality that inhibits our country's growth and limits the ability of low-income, African Americans to cope with an unforeseen crisis.

These are investments we can make. Every dollar invested in building resilience and reducing exposure to disaster risks saves $4 in disaster response and recovery. Not to mention the moral obligation our country has in addressing the fact that our policies have put black people in harm's way.

Hurricane Katrina was once labeled the storm of the century, but it is increasingly apparent that events of this scale are part of the new normal. At the same time, the legacies of segregation and disinvestment have trapped black people in communities at greatest risk. As the Black Lives Matter movement continues to advocate for the health and wealth of black communities, we must recognize that climate change is one of the most important civil rights issues of our day.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

In the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, 80 percent of New Orleans was under water, thousands of people were displaced, and at least 1,800 people were killed. The country watched in disbelief as residents -- a disproportionate number of whom were black -- pleaded for help on rooftops as then-President George W. Bush watched from afar -- first from Washington, D.C., then overhead from a helicopter. All the while, the city's poorest community, the Lower Ninth Ward, had up to 12 feet of water sitting stagnant in some areas for weeks. It was the last place to have power and water service restored, and the last to have the flood waters pumped out.

Despite the dire circumstances, news outlets and law enforcement quickly began to label the black residents as "looters." They were not viewed as people trying to survive, but rather as criminals who needed to be reined in. New Orleans Police Department Captain James Scott instructed police officers that they had the "authority by martial law to shoot looters."

And that's what they did: All told, 11 people were shot by law enforcement officials following the storm. The most well-known incident occurred six days after Katrina hit, when members of the NOPD -- unprovoked and armed with assault rifles -- stormed the Danziger Bridge and began firing on a group of unarmed civilians in search of food. Two people were killed, including a mentally disabled man who was shot in the back and a 19-year-old high school student. Four more were seriously injured, including three members of the Bartholomew family. Leonard Bartholomew suffered a gunshot wound to the head, his daughter was wounded in the abdomen, and his wife Susan lost an arm due to the severity of the gun blast that hit her. Five officers were arrested and convicted. Ten years later, the Bartholomew family's civil suit remains unsettled.

The feeling that black lives did not matter was most famously summed up by rapper Kanye West when he stated firmly during a primetime telethon that "George Bush doesn't care about Black people."

As Hurricane Katrina revealed, the consequences of poverty, segregation, police brutality, and environmental racism coming to a head have tragic results.

Amidst the growing threat of climate change, this perfect storm must not be forgotten. While an extreme weather event, such as a flood, heat wave, or hurricane may seem like an equal opportunity force of destruction, in reality these events exacerbate the underlying injustices that exist in our communities year round. Understanding just how vulnerable low-income, black communities are to these threats is critical to protecting black lives in the 21st century.

Today, much of New Orleans is back to normal, with more than half of the city's neighborhoods reaching their pre-storm population levels. However, that's far from the case for the infamous Lower Ninth Ward. In the years following Katrina, only about 37 percent of households have returned home. Black residents who wanted to rebuild simply couldn't afford to as federal aid was allocated based on home values rather than the cost of construction. The average gap between the damage accrued and the grants awarded to residents of the Lower Ninth Ward was $75,000, more than twice the average household income of the residents there.

As Professor Beverly Wright of Loyola University New Orleans explained, "pre-storm vulnerabilities continue to limit the participation of thousands of disadvantaged individuals and communities in the after-storm reconstruction, rebuilding, and recovery. In these communities, days of hurt and loss have become years of grief, dislocation, and displacement."

As Hurricane Katrina revealed, the consequences of poverty, segregation, police brutality, and environmental racism coming to a head have tragic results.

Hurricane Katrina exposed that even in our hour of greatest need, black people are often not afforded the tragic gift of vulnerability. Instead, we are an ever present threat.

Today's #BlackLivesMatter movement -- a national call to action and response against "extrajudicial killings of Black people by police and vigilantes" -- is focused on just that. The movement demands accountability of law enforcement, while affirming the need to invest in low-income, black communities "in order to create jobs, housing and schools." It is this last demand that is often left out of media discussions of the movement, but is critical to the health, wealth, and well-being of African American families.

The legacy of segregation and disinvestment

While the United States is known as the "land of opportunity" the world over, a more accurate description is that the U.S. is composed of disparate lands of opportunity. Earlier this year, Harvard economist Raj Chetty, along with his colleagues, released two studies that add to the growing body of research that your zip code determines your life chances.

Orleans Parish in Louisiana -- where New Orleans is located -- is among the worst counties in the U.S. for children in poor families, according to Chetty's findings. A child born in this part of Louisiana makes approximately 19 percent less when she turns 26 than if her family moved to an average place when she was a small child. This is the story of many communities across the country, as concentrated poverty persists and low-income communities and communities of color face inferior housing, poor air quality, failing schools, inadequate public infrastructure, and few employment opportunities. Black families live in these communities at disproportionate numbers and, as past policies reveal, this was by design.

For decades, the federal government invested in the stability of affluent, predominantly white communities, while giving localities the authority to neglect low-income communities and communities of color. Such practices included everything from redlining, beginning in the 1930s, where banks were allowed to exclude African American communities from receiving home loans, to the expansion of the highway system, which rammed through and destroyed African American businesses and homes in the process.

Today, the average African American family making $100,000 a year lives in a more disadvantaged neighborhood -- characterized by racial segregation, high rates of poverty and unemployment, and exposure to neighborhood violence -- than the average white family making $30,000 a year, revealing how past social policies continue to affect neighborhood choice. It is this lack of choice that is putting black lives at risk and, in some instances, directly in the path of extreme weather events.

Vulnerability to extreme weather

On October 29, 2012, Superstorm Sandy hit the northeastern United States and became the second costliest storm in U.S. history after Katrina. Heeding the lessons from the blundered response in New Orleans, the federal government was quick to act with Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) officials arriving throughout the region and President Barack Obama surveying the damage from the ground.

Despite the quick response, the region suffered greatly, with low-income people and people of color shouldering a disproportionate share of the damage and chaos. In New York City, many low-income, elderly, and disabled residents were stranded in public housing towers for weeks after the storm due to elevator outages. Other residents remained in the high rises, despite having no heat or power, because they had nowhere else to go. The storm served as a reminder of just how vulnerable low-income, communities of color are to such disasters.

Given the enduring legacy of discrimination and segregation in the United States, it is not surprising that millions of black families are forced to live in neighborhoods that are accessible to them precisely because these neighborhoods are at greatest risk.

On top of living in poor quality housing stock, which is older and more susceptible to damage, black households disproportionately live near industrial sites like chemical plants and refineries, which can cause toxic spills during storms. Furthermore, due to a greater likelihood of living in close proximity to waste facilities, people of color are disproportionately impacted by storm debris removal in the aftermath of extreme weather events.

Given the enduring legacy of discrimination and segregation in the United States, it is not surprising that millions of black families are forced to live in neighborhoods that are accessible to them precisely because these neighborhoods are at greatest risk.

And with the black unemployment rate more than twice the rate among whites, black households have a harder time bouncing back after disasters. This is particularly the case for non-salaried workers, who, as Ross Eisenbrey, vice president of the Economic Policy Institute, explains are at the mercy of their employers: "If the business closes because of the storm, employers don't have to pay non-salaried workers for lost wages. And if the business is open, but the worker can't make it into work, employers are also not required to pay for lost wages."

Building resilient communities

While much of the nation was outraged at Bush's failed response to Katrina, we should remain similarly outraged at the risks black communities continue to endure year round. Last year alone, the United States experienced eight severe weather, flood, and drought events, causing $19 billion in damages across 35 states, and cost us 65 human lives. Each year, extreme heat -- one of the leading weather-related killers in the U.S. -- results in hundreds of fatalities, particularly in inner-city neighborhoods that tend to be several degrees hotter than other communities due to the presence of fewer trees and more asphalt.

Climate change has become an ever-present Katrina.

Earlier this month, President Obama reaffirmed his commitment to cutting carbon pollution -- the leading contributor to climate disruption caused by human activities -- by announcing the most significant action that any American president has made to address the very real threat of climate change. At the same time, a new poll by The Washington Post revealed that 60 percent of Americans believe the county must continue making changes to give blacks and whites equal rights, compared to just 46 percent last year. We're at a unique juncture in our nation's history where the public increasingly recognizes that once seemingly intractable problems are our responsibility.

While the Obama administration has taken great steps to ensure our nation's communities are more resilient in the face of climate-fueled extreme weather, the outsized consequences of these events on poor, black communities requires special attention. It requires the backing of a movement. It requires that in every policy debate, we constantly affirm that black lives matter.

We cannot ignore our nation's housing crisis, the environmental justice issues that plague our communities, and the growing economic inequality that inhibits our country's growth and limits the ability of low-income, African Americans to cope with an unforeseen crisis.

These are investments we can make. Every dollar invested in building resilience and reducing exposure to disaster risks saves $4 in disaster response and recovery. Not to mention the moral obligation our country has in addressing the fact that our policies have put black people in harm's way.

Hurricane Katrina was once labeled the storm of the century, but it is increasingly apparent that events of this scale are part of the new normal. At the same time, the legacies of segregation and disinvestment have trapped black people in communities at greatest risk. As the Black Lives Matter movement continues to advocate for the health and wealth of black communities, we must recognize that climate change is one of the most important civil rights issues of our day.

In the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, 80 percent of New Orleans was under water, thousands of people were displaced, and at least 1,800 people were killed. The country watched in disbelief as residents -- a disproportionate number of whom were black -- pleaded for help on rooftops as then-President George W. Bush watched from afar -- first from Washington, D.C., then overhead from a helicopter. All the while, the city's poorest community, the Lower Ninth Ward, had up to 12 feet of water sitting stagnant in some areas for weeks. It was the last place to have power and water service restored, and the last to have the flood waters pumped out.

Despite the dire circumstances, news outlets and law enforcement quickly began to label the black residents as "looters." They were not viewed as people trying to survive, but rather as criminals who needed to be reined in. New Orleans Police Department Captain James Scott instructed police officers that they had the "authority by martial law to shoot looters."

And that's what they did: All told, 11 people were shot by law enforcement officials following the storm. The most well-known incident occurred six days after Katrina hit, when members of the NOPD -- unprovoked and armed with assault rifles -- stormed the Danziger Bridge and began firing on a group of unarmed civilians in search of food. Two people were killed, including a mentally disabled man who was shot in the back and a 19-year-old high school student. Four more were seriously injured, including three members of the Bartholomew family. Leonard Bartholomew suffered a gunshot wound to the head, his daughter was wounded in the abdomen, and his wife Susan lost an arm due to the severity of the gun blast that hit her. Five officers were arrested and convicted. Ten years later, the Bartholomew family's civil suit remains unsettled.

The feeling that black lives did not matter was most famously summed up by rapper Kanye West when he stated firmly during a primetime telethon that "George Bush doesn't care about Black people."

As Hurricane Katrina revealed, the consequences of poverty, segregation, police brutality, and environmental racism coming to a head have tragic results.

Amidst the growing threat of climate change, this perfect storm must not be forgotten. While an extreme weather event, such as a flood, heat wave, or hurricane may seem like an equal opportunity force of destruction, in reality these events exacerbate the underlying injustices that exist in our communities year round. Understanding just how vulnerable low-income, black communities are to these threats is critical to protecting black lives in the 21st century.

Today, much of New Orleans is back to normal, with more than half of the city's neighborhoods reaching their pre-storm population levels. However, that's far from the case for the infamous Lower Ninth Ward. In the years following Katrina, only about 37 percent of households have returned home. Black residents who wanted to rebuild simply couldn't afford to as federal aid was allocated based on home values rather than the cost of construction. The average gap between the damage accrued and the grants awarded to residents of the Lower Ninth Ward was $75,000, more than twice the average household income of the residents there.

As Professor Beverly Wright of Loyola University New Orleans explained, "pre-storm vulnerabilities continue to limit the participation of thousands of disadvantaged individuals and communities in the after-storm reconstruction, rebuilding, and recovery. In these communities, days of hurt and loss have become years of grief, dislocation, and displacement."

As Hurricane Katrina revealed, the consequences of poverty, segregation, police brutality, and environmental racism coming to a head have tragic results.

Hurricane Katrina exposed that even in our hour of greatest need, black people are often not afforded the tragic gift of vulnerability. Instead, we are an ever present threat.

Today's #BlackLivesMatter movement -- a national call to action and response against "extrajudicial killings of Black people by police and vigilantes" -- is focused on just that. The movement demands accountability of law enforcement, while affirming the need to invest in low-income, black communities "in order to create jobs, housing and schools." It is this last demand that is often left out of media discussions of the movement, but is critical to the health, wealth, and well-being of African American families.

The legacy of segregation and disinvestment

While the United States is known as the "land of opportunity" the world over, a more accurate description is that the U.S. is composed of disparate lands of opportunity. Earlier this year, Harvard economist Raj Chetty, along with his colleagues, released two studies that add to the growing body of research that your zip code determines your life chances.

Orleans Parish in Louisiana -- where New Orleans is located -- is among the worst counties in the U.S. for children in poor families, according to Chetty's findings. A child born in this part of Louisiana makes approximately 19 percent less when she turns 26 than if her family moved to an average place when she was a small child. This is the story of many communities across the country, as concentrated poverty persists and low-income communities and communities of color face inferior housing, poor air quality, failing schools, inadequate public infrastructure, and few employment opportunities. Black families live in these communities at disproportionate numbers and, as past policies reveal, this was by design.

For decades, the federal government invested in the stability of affluent, predominantly white communities, while giving localities the authority to neglect low-income communities and communities of color. Such practices included everything from redlining, beginning in the 1930s, where banks were allowed to exclude African American communities from receiving home loans, to the expansion of the highway system, which rammed through and destroyed African American businesses and homes in the process.

Today, the average African American family making $100,000 a year lives in a more disadvantaged neighborhood -- characterized by racial segregation, high rates of poverty and unemployment, and exposure to neighborhood violence -- than the average white family making $30,000 a year, revealing how past social policies continue to affect neighborhood choice. It is this lack of choice that is putting black lives at risk and, in some instances, directly in the path of extreme weather events.

Vulnerability to extreme weather

On October 29, 2012, Superstorm Sandy hit the northeastern United States and became the second costliest storm in U.S. history after Katrina. Heeding the lessons from the blundered response in New Orleans, the federal government was quick to act with Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) officials arriving throughout the region and President Barack Obama surveying the damage from the ground.

Despite the quick response, the region suffered greatly, with low-income people and people of color shouldering a disproportionate share of the damage and chaos. In New York City, many low-income, elderly, and disabled residents were stranded in public housing towers for weeks after the storm due to elevator outages. Other residents remained in the high rises, despite having no heat or power, because they had nowhere else to go. The storm served as a reminder of just how vulnerable low-income, communities of color are to such disasters.

Given the enduring legacy of discrimination and segregation in the United States, it is not surprising that millions of black families are forced to live in neighborhoods that are accessible to them precisely because these neighborhoods are at greatest risk.

On top of living in poor quality housing stock, which is older and more susceptible to damage, black households disproportionately live near industrial sites like chemical plants and refineries, which can cause toxic spills during storms. Furthermore, due to a greater likelihood of living in close proximity to waste facilities, people of color are disproportionately impacted by storm debris removal in the aftermath of extreme weather events.

Given the enduring legacy of discrimination and segregation in the United States, it is not surprising that millions of black families are forced to live in neighborhoods that are accessible to them precisely because these neighborhoods are at greatest risk.

And with the black unemployment rate more than twice the rate among whites, black households have a harder time bouncing back after disasters. This is particularly the case for non-salaried workers, who, as Ross Eisenbrey, vice president of the Economic Policy Institute, explains are at the mercy of their employers: "If the business closes because of the storm, employers don't have to pay non-salaried workers for lost wages. And if the business is open, but the worker can't make it into work, employers are also not required to pay for lost wages."

Building resilient communities

While much of the nation was outraged at Bush's failed response to Katrina, we should remain similarly outraged at the risks black communities continue to endure year round. Last year alone, the United States experienced eight severe weather, flood, and drought events, causing $19 billion in damages across 35 states, and cost us 65 human lives. Each year, extreme heat -- one of the leading weather-related killers in the U.S. -- results in hundreds of fatalities, particularly in inner-city neighborhoods that tend to be several degrees hotter than other communities due to the presence of fewer trees and more asphalt.

Climate change has become an ever-present Katrina.

Earlier this month, President Obama reaffirmed his commitment to cutting carbon pollution -- the leading contributor to climate disruption caused by human activities -- by announcing the most significant action that any American president has made to address the very real threat of climate change. At the same time, a new poll by The Washington Post revealed that 60 percent of Americans believe the county must continue making changes to give blacks and whites equal rights, compared to just 46 percent last year. We're at a unique juncture in our nation's history where the public increasingly recognizes that once seemingly intractable problems are our responsibility.

While the Obama administration has taken great steps to ensure our nation's communities are more resilient in the face of climate-fueled extreme weather, the outsized consequences of these events on poor, black communities requires special attention. It requires the backing of a movement. It requires that in every policy debate, we constantly affirm that black lives matter.

We cannot ignore our nation's housing crisis, the environmental justice issues that plague our communities, and the growing economic inequality that inhibits our country's growth and limits the ability of low-income, African Americans to cope with an unforeseen crisis.

These are investments we can make. Every dollar invested in building resilience and reducing exposure to disaster risks saves $4 in disaster response and recovery. Not to mention the moral obligation our country has in addressing the fact that our policies have put black people in harm's way.

Hurricane Katrina was once labeled the storm of the century, but it is increasingly apparent that events of this scale are part of the new normal. At the same time, the legacies of segregation and disinvestment have trapped black people in communities at greatest risk. As the Black Lives Matter movement continues to advocate for the health and wealth of black communities, we must recognize that climate change is one of the most important civil rights issues of our day.