Thousands of prisoners will be moved out of solitary confinement in California, thanks to a landmark legal settlement announced this week. Grass-roots organizing can be tough, but when done by prisoners locked up in solitary confinement, some of them for decades, it is astounding. The settlement grew out of a federal class-action lawsuit alleging violations of the constitutional prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment.

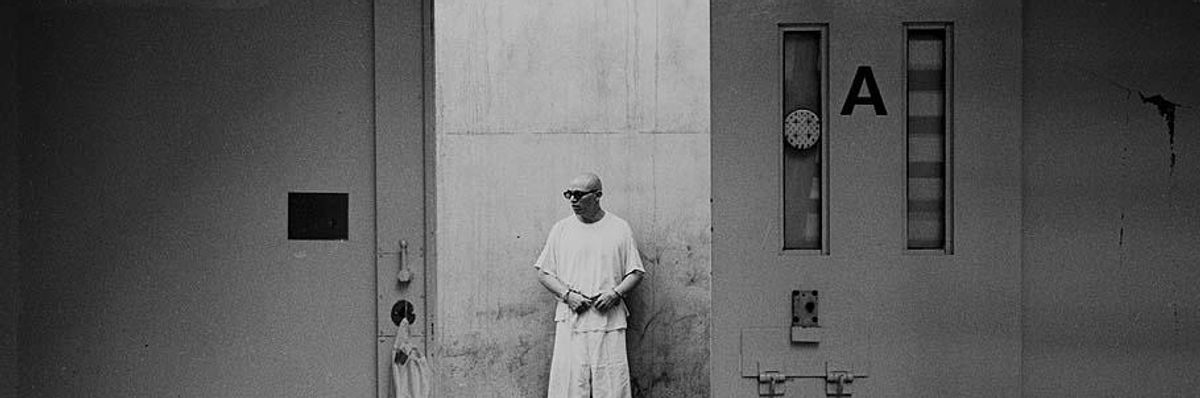

They call themselves the Pelican Bay SHU Short Corridor Collective. This group of men has been subjected to long-term solitary confinement, some for more than 20 years, in California's Pelican Bay State Prison, located in the far northern corner of the state. From within their small, windowless cells, they began talking, organizing. In July 2011, they launched a hunger strike in protest of conditions in the "SHU" (pronounced "shoe"), the Security Housing Unit, Pelican Bay's solitary-confinement facility. More than 1,000 SHU prisoners joined in. They issued five demands, and after three weeks, officials offered what the hunger strikers considered a good-faith pledge to review policies in the SHU. Months later, after no action was taken, they went on a hunger strike again. This time, more than 12,000 prisoners joined in, across California and even in other states.

The Center for Constitutional Rights, a public-interest law firm with a focus on human rights, filed suit on behalf of all prisoners in California's prison system who had been accused of gang affiliation and, thus, sent to the SHU. As the lawsuit wended its way through the legal system, a third hunger strike was initiated, in July 2013. More than 60,000 prisoners took part. A movement was growing.

Outside, family members had been showing support, forming the group California Families Against Solitary Confinement. Dolores Canales' son, John Martinez, had been in solitary for more than 14 years. He has participated in all three hunger strikes. "He's written me, saying that he has no doubt in his mind that Pelican Bay Security Housing Unit was designed solely to drive men mad or to suicide," Canales told us after the settlement was announced this week. "I didn't even realize the circumstances of solitary confinement, the depth of the isolation."

When asked how the families organized, she reflected: "I wouldn't even be here at this moment if it were not for the hundreds of family members that have come out ... every hunger strike that they had was during the summer--July, August and September--you know, these warm months. Yet family members would be outside every other day dressed in orange jumpsuits, carrying chains or handcuffs or bullhorns, to draw attention of society, conducting numerous panels at universities and churches, and just organizing and mobilizing across the state of California, raising awareness to these conditions that our loved ones were enduring."

Prisoner Todd Ashker is one of the Pelican Bay SHU Short Corridor Collective organizers. Since he gets no phone calls, access to his voice is difficult. In one recording from the time of the hunger strikes, obtained by the "Democracy Now!" news hour, Ashker, who is the named plaintiff in the case that led to the settlement, said: "Most of us have never been found guilty of ever committing an illegal gang-related act. But we're in SHU because of a label. And all of our appeals, numerous court challenges, have gotten nowhere. Therefore, our backs are up against the wall." In one deposition, Ashker described how prison officials bolted plexiglass to the front wall of the SHU cells to inhibit the collective's ability to speak to one another, in retaliation for their organizing.

Prolonged solitary confinement is torture. The United Nations Special Rapporteur on Torture, Juan Mendez, reported in 2011: "Segregation, isolation, separation, cellular, lockdown, Supermax, the hole, Secure Housing Unit ... whatever the name, solitary confinement should be banned by States as a punishment."

"Solitary confinement," says Jules Lobel, president of the Center for Constitutional Rights and the lead attorney in the case, "makes [prisoners] very angry, frustrated, hopeless, which all of our guys have experienced ... it creates what social scientists call a social death. People lose their ability to relate to ... people in the normal world."

It's not only prisoners and their families opposed to solitary. One day after the settlement was reached, the Association of State Correctional Administrators released a statement that read in part: "Prolonged isolation of individuals in jails and prisons is a grave problem in the United States. The insistence on change comes not only from legislators across the political spectrum, judges, and a host of private sector voices, but also from the directors of correctional systems at both state and federal levels ... it's the right thing to do."