Zika and the epidemic of birth defects, like the lead poisoning in Flint, highlight the added burdens especially facing the poor and people of color.

There are striking similarities between the lead-poisoned water hurting Flint citizens and the burdens facing Latin American women with babies born with microcephaly, likely due to Zika infections.

What do these two tragedies have in common? They--and many other similar problems--largely affect poor people of color, people who are politically powerless.

Environmental racism

The lead poisoning travesty in Flint occurred because Governor Rick Snyder replaced local representatives with an emergency manager system intended to wring savings out of communities, and damn the human cost. Flint's water supply was changed from Lake Huron water, treated by Detroit, to water from the historically very polluted Flint River, and they didn't bother to add necessary anticorrosives, to save ~$100/day. The cost to repair the damage is estimated as $1.5 billion.

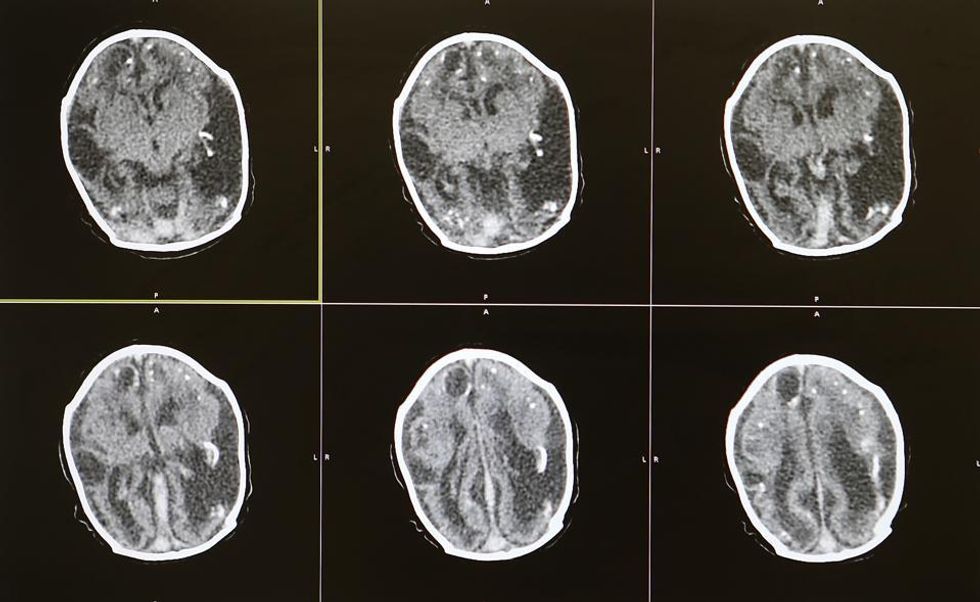

Now, the community has been drinking lead-tainted water, toxic at any level, and which can cause lasting brain damage likely to scar an entire generation of Flint children, as I outlined in my previous post. As pediatrician and whistleblower Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha explained, "We don't see the illness of lead right now, we see the consequences over the entire life of the child through their adulthood... Lead is an irreversible neurotoxin with a lifelong, multi-generational impact. And we just had a whole population exposed to it."

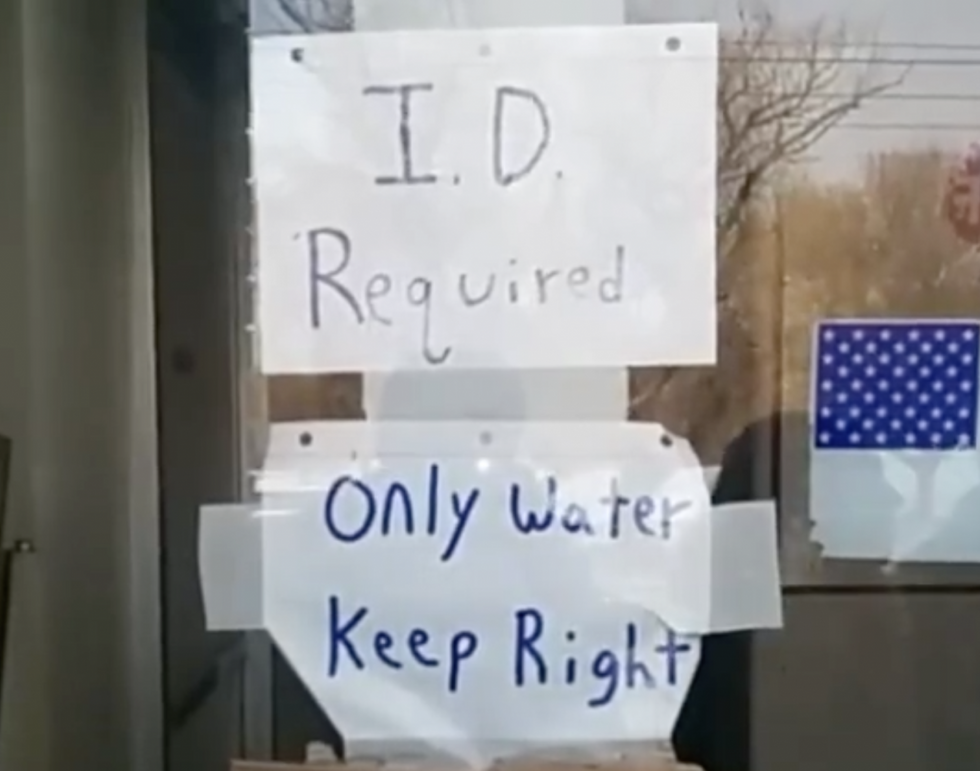

Flint is a poor city, more than half African American, with 40% living in poverty. Even within Flint, there are pockets that are more marginalized. Language barriers have hampered awareness of the problem in Arab American and Hispanic communities within the city. Undocumented immigrants are justifiably afraid to get help, given the recent increase in ICE raids and deportations. This week a sign appeared telling people coming for bottled water that they would need to produce identification.

It was later removed.

Similar problems have been happening across the country--in Washington, D.C., where Virginia Tech's Marc Edwards previously showed extensive lead poisoning, for example.

It's not just lead poisoning. Access to clean water is considered a human right by the United Nations, yet many, even in poor areas of the U.S., don't have this.

Zika

There have been about 4,000 babies born with microcephaly (abnormally small skulls) in the past year in Brazil alone, and this serious birth defect is now being seen more widely throughout Latin America and the Caribbean. While not entirely proven, it is highly likely that Zika virus causes the microcephaly. Countries are advising women to delay pregnancy, and the U.S. and other countries have issued travel warnings to women who might be pregnant or are trying to become pregnant to avoid travel to affected countries. The most outrageous suggestion came from El Salvador, which recommended women delay pregnancies for two full years. How impractical is that?

If we look carefully at the contraceptive accessibility data and social justice aspects of the Zika outbreak, surprisingly, published data on contraceptive use in Latin America suggests that ~76% of women use contraception. This number seems shockingly high to me, given the conservative Catholic and Evangelical influence in the region. I turned to Beatriz Galli, Senior Latin America Policy Advisor for Ipas, a global reproductive rights nongovernmental organization, for clarification. Speaking from Brazil, she stressed that the surveys yielding these findings were done in married women and that the answers likely reflected use of a contraceptive at any time--not current or sustained or correct use. While family planning laws are in place and Ministries of Health are providing contraceptives, access to these are quite variable, and are "not reaching marginalized, poor or rural" areas as they should. There is almost a complete "lack of access of sexual education in schools. Because of pressure of religion, women in poor and rural areas are likely not to have access to the information needed or right methods to plan their pregnancies." Similarly, she felt data about teens having a high use of contraceptives (in some LAC countries) is misleading. "Adolescents aren't given the right information. Sometimes they don't have confidentiality...there are problems with continuity," as well. The "high rate of teen pregnancy confirms that governments are failing to provide proper access to information and services they may need."

The Guttmacher Institute reports Latin America and the Caribbean countries have the highest rate of unintended pregnancies in the world--56%. Physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence is reported by 30% of women in the region. Similar data is reported by PAHO.

Given these disturbing numbers regarding partner violence, Galli believes the government recommendations to delay pregnancy are totally unrealistic. She observes there are "unequal power relations in this very patriarchal society" and emphasizes that the governments are putting the onus on individual women--with their limited autonomy--rather than assuming responsibility to deal with the public health crisis. "Zika is major public health crisis with potentially devastating consequences for women and girls of reproductive age and their families."

Women bear the burden

What happens to poor women who become pregnant due to lack of access to contraceptives, or rape or domestic violence?

Not surprisingly, unplanned births in the U.S. are associated with delayed prenatal care, poorer mental and physical health, and poorer outcomes for the child.

Many women in other countries fare even more poorly. "Nearly half the world's population, 2.8 billion people, survive on less than $2 a day. About 20% of the world's population, 1.2 billion people, live on less than $1 a day;" 60% of those living in extreme poverty are women. Women also comprise 64% of those who are illiterate.

The CDC recommends enhanced monitoring with serial ultrasounds during pregnancy for women who had Zika infections. This is great in helping our understanding of the newly emerging disease, but does little for the affected women, except perhaps alert them to an impending tragedy.

Many infections, as well as toxins or chromosomal abnormalities, can cause microcephaly. It's important to note that the incidence of this birth defect is estimated at 0.2% to 1% in Zika-affected regions. There is increasing evidence that Zika is causing the current epidemic of microcephaly. "Microcephaly can be caused by so many different things and many times is not diagnosed until after the newborn period," notes Marjorie Treadwell, a maternal and fetal medicine professor at the University of Michigan. Gustavo Mallinger, an OB-GYN and expert on fetal ultrasonography in Israel has additional worries. He told me, "Most of the children with microcephaly are born with a normal head circumference and develop microcephaly during the first year of life." He adds that with Zika, the problem is not the diminished skull size per se, but the severity of the underlying infection that it reflects. "The truly important issue will be how to identify fetuses with less severe disease that will turn out probably to be blind, deaf or mentally retarded. In these cases termination of pregnancy should be an option if acceptable for the family and under the law."

There's the rub. Abortion is illegal throughout Latin America, in many places even to save the life of the mother. And microcephaly is often not detected until 24-28 weeks gestation, when abortion is illegal in the U.S. (though in many states, it is illegal far earlier).

Abortion prohibitions disproportionately affect poor women, as recounted in "Pregnant and Desperate in Evangelical Brazil." The Guttmacher Institute reports that 95% of abortions in LAC were unsafe by WHO standards--performed by an individual without the necessary skills, or in an environment that does not conform to the minimum medical standards, or both. They numbered 31/1,000 women, with only 2/1,000 considered "safe." About 760,000 women in Latin America and the Caribbean are hospitalized annually for treatment of complications from unsafe abortion. Because of stigma, cost and legal consequences, many others get inadequate care.

What will happen with the growing microcephaly epidemic?

Poor women will likely have more infections than their more affluent counterparts, as they are more likely to live in urban slums with pools of standing water, ideal mosquito breeding grounds. They are also more likely to live in dilapidated housing without adequate screens or protective air conditioning.

Poor women--both in Latin America and in the Gulf states of the U.S., where Zika will likely hit hard, will increasingly turn to unsafe abortions. Those who are unsuccessful, or even those who unintentionally have a miscarriage, or a stillbirth, are likely to face barbaric feticide laws and imprisonment, as happened in Indiana in 2014, and more often since then, here and in Latin America.

Poor women who have a baby born with microcephaly and associated mental retardation, deafness or blindness will also carry a disproportionate burden for their infant's future care. There is inadequate support for them both in LAC and in the Gulf states, which most strongly opposed Medicaid expansion and social services for their citizens. Once born, the needs of the children and mothers are often forgotten.

As Galli emphasized, Zika "is a social justice issue-only poor and disadvantaged women living in poor urban and rural areas are likely to be more affected. They should not be told to delay pregnancy or to continue to be pregnant against their will. This is a violation to their dignity and their reproductive rights."

Conclusion

While the epidemic of Zika and lead poisoning might at first glance seem unrelated, they both reflect the disproportionate burden facing poor people, and especially poor women of color, globally. They raise serious ethical and human rights issues, including access to safe water, safe living environments and autonomy. Placing the burden of avoiding pregnancy on poor women is unconscionable and unfeasible, especially where access to contraception is limited, and where women may be unable to "just say no" to sexual relations without risking partner violence. Finally, the disasters of both Flint and Zika reflect the failure of governments to protect their citizens.