SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

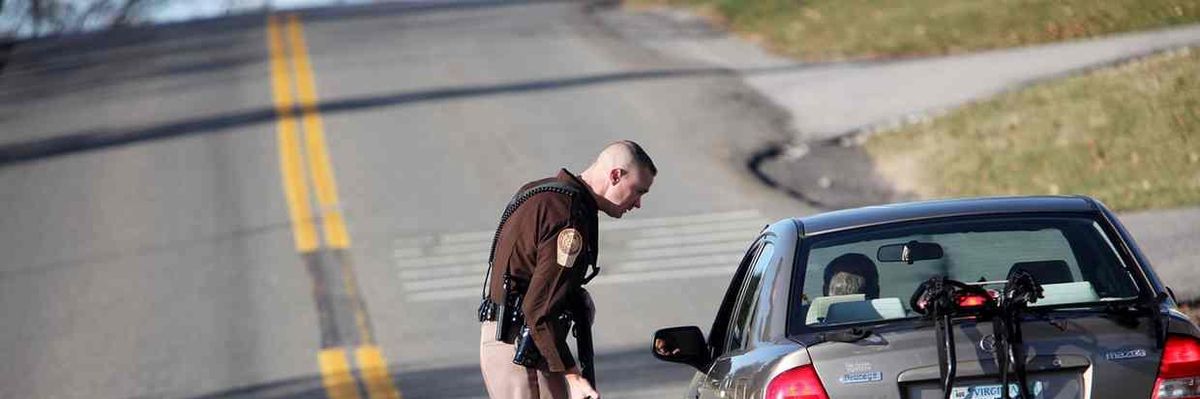

'Across the country, cash-hungry courts squeeze money in the form of fines and fees from the very citizens who can least afford them.' (Photo: Kyle Green/AP)

Soon after the horrific video of Minneapolis-St Paul resident Philando Castile being killed by a cop during a routine traffic stop was broadcast live over Facebook, evidence of just how "routine" the stop actually was also became public.

Castile, it turned out, had been pulled over at least 52 times in 13 years for a variety of minor infractions - a broken seat belt, an unlit license plate, tinted windows, a missing muffler - or what his mother called "driving while black".

Across the country, cash-strapped courts squeeze money in the form of fines and fees from the very citizens who can least afford them. Over the course of those 13 years, Castile was charged over $6,500. And too often, when people can't pay, they wind up jail - sometimes for fines associated with things as trivial as a missing trash can lid or illegally parking - which is why advocates now talk about the "criminalization of poverty" and the return of "debtors' prisons".

Municipal budgets are overly reliant on petty infraction penalties because affluent, mostly white citizens have been engaged in a "tax revolt" for decades, lobbying for lower rates and special treatment.

This cycle has to be broken.

Some civic-minded lawyers are successfully bringing class-action suits in various states to halt unfair practices at the municipal level, including excess fines and fees and the use of for-profit probation services, while also arguing that jailing debtors is unconstitutional. As a consequence of these efforts, Jennings, Missouri recently settled to pay nearly $5m to 2,000 citizens who were locked up for unpaid court debts.

But in addition to lawsuits to help protect the poor, the rich must start pulling their weight. We need to fine people more the richer they are - penalties should be proportionate to income, not flat-rate. After all, a $200 sanction means a hell of a lot more to a single parent making minimum wage than to an executive raking in a six- or seven-figure income. Maybe the former should pay only $20, the latter $2,000 or even $20,000.

That's how many other countries do it. Finland, Switzerland, Sweden, Denmark, Germany, Austria and France all have some form of sliding-scale fines in place for offenses ranging from traffic tickets to petty theft and assault.

Every few years, there are news stories reporting on exotic, exorbitant European speeding tickets. There was the Finnish businessman who was hit with one for EUR54,024 (about $60,000) last spring for driving 64mph in a 50mph zone, or the Ferrari-driving Swiss repeat offender who made headlines with a record fine of PS182,000 (about $237,000). Such colossal fines are rare, but penalties calculated according to earnings are commonplace.

"This is a Nordic tradition," a Finnish government adviser told the Wall Street Journal over a decade ago, explaining principles that have been in place since the 1920s. "We have progressive taxation and progressive punishments. So the more you earn, the more you pay."

In the US, we still have progressive taxation, at least until Ted Cruz gets his way and institutes a flat tax. Now we need progressive punishment to match. Back in the 80s the National Institute of Justice supported pilot programs involving sliding-scale fines in Staten Island and Milwaukee. The idea didn't catch on, despite (or perhaps because of) the fact that the results were promising (in Milwaukee overall revenue went down, pegged as it was to mostly low-income defendants' ability to pay; in Staten Island, a combination of proportional fines and new collection practices led to a fewer arrest warrants related to nonpayment). But today, thanks to the effective work of the Black Lives Matter movement, the public is far more aware - and outraged - about the inequities of criminal justice system and may be more open to new approaches.

Some might object that progressive punishment would lead to police unfairly targeting the wealthy. One can imagine officers lying in wait for a juicy Porsche or Tesla to race by (which might actually be a boon to public safety, since studies have linked bad driving and increased wealth).

But such an image belittles the reality many communities of color and low-income people already face. A recent ACLU report on policing in Castile's home of Minneapolis found that black people are 8.7 times more likely than their white counterparts to be arrested for low-level offenses. Or, as NYPD officer Derick Waller told NBC this spring, comparing arrest quotas to bounty hunting: "The problem is when you go hunting, when you pull any type of numbers for a police officer to perform, we are gonna go to the most vulnerable. We're gonna go to the LGBT community, we're gonna go to the black community."

Progressive punishment isn't a universal panacea and won't fix the complex issues of mass incarceration or entrenched racism. But if combined with other smart policies - increasing income and property taxes in some places, reining in ticketing more generally, eliminating debtors' prisons, ending for-profit policing, creating real community oversight and so on - it could be part of the solution to some of the problems recent tragedies have exposed.

Making it possible to issue bigger tickets for people at the top of the income hierarchy might shift police incentives and help end the government-led shakedown of the poor that is currently ruining - and ending - lives.

This piece was supported by Economic Hardship Reporting Project.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

Soon after the horrific video of Minneapolis-St Paul resident Philando Castile being killed by a cop during a routine traffic stop was broadcast live over Facebook, evidence of just how "routine" the stop actually was also became public.

Castile, it turned out, had been pulled over at least 52 times in 13 years for a variety of minor infractions - a broken seat belt, an unlit license plate, tinted windows, a missing muffler - or what his mother called "driving while black".

Across the country, cash-strapped courts squeeze money in the form of fines and fees from the very citizens who can least afford them. Over the course of those 13 years, Castile was charged over $6,500. And too often, when people can't pay, they wind up jail - sometimes for fines associated with things as trivial as a missing trash can lid or illegally parking - which is why advocates now talk about the "criminalization of poverty" and the return of "debtors' prisons".

Municipal budgets are overly reliant on petty infraction penalties because affluent, mostly white citizens have been engaged in a "tax revolt" for decades, lobbying for lower rates and special treatment.

This cycle has to be broken.

Some civic-minded lawyers are successfully bringing class-action suits in various states to halt unfair practices at the municipal level, including excess fines and fees and the use of for-profit probation services, while also arguing that jailing debtors is unconstitutional. As a consequence of these efforts, Jennings, Missouri recently settled to pay nearly $5m to 2,000 citizens who were locked up for unpaid court debts.

But in addition to lawsuits to help protect the poor, the rich must start pulling their weight. We need to fine people more the richer they are - penalties should be proportionate to income, not flat-rate. After all, a $200 sanction means a hell of a lot more to a single parent making minimum wage than to an executive raking in a six- or seven-figure income. Maybe the former should pay only $20, the latter $2,000 or even $20,000.

That's how many other countries do it. Finland, Switzerland, Sweden, Denmark, Germany, Austria and France all have some form of sliding-scale fines in place for offenses ranging from traffic tickets to petty theft and assault.

Every few years, there are news stories reporting on exotic, exorbitant European speeding tickets. There was the Finnish businessman who was hit with one for EUR54,024 (about $60,000) last spring for driving 64mph in a 50mph zone, or the Ferrari-driving Swiss repeat offender who made headlines with a record fine of PS182,000 (about $237,000). Such colossal fines are rare, but penalties calculated according to earnings are commonplace.

"This is a Nordic tradition," a Finnish government adviser told the Wall Street Journal over a decade ago, explaining principles that have been in place since the 1920s. "We have progressive taxation and progressive punishments. So the more you earn, the more you pay."

In the US, we still have progressive taxation, at least until Ted Cruz gets his way and institutes a flat tax. Now we need progressive punishment to match. Back in the 80s the National Institute of Justice supported pilot programs involving sliding-scale fines in Staten Island and Milwaukee. The idea didn't catch on, despite (or perhaps because of) the fact that the results were promising (in Milwaukee overall revenue went down, pegged as it was to mostly low-income defendants' ability to pay; in Staten Island, a combination of proportional fines and new collection practices led to a fewer arrest warrants related to nonpayment). But today, thanks to the effective work of the Black Lives Matter movement, the public is far more aware - and outraged - about the inequities of criminal justice system and may be more open to new approaches.

Some might object that progressive punishment would lead to police unfairly targeting the wealthy. One can imagine officers lying in wait for a juicy Porsche or Tesla to race by (which might actually be a boon to public safety, since studies have linked bad driving and increased wealth).

But such an image belittles the reality many communities of color and low-income people already face. A recent ACLU report on policing in Castile's home of Minneapolis found that black people are 8.7 times more likely than their white counterparts to be arrested for low-level offenses. Or, as NYPD officer Derick Waller told NBC this spring, comparing arrest quotas to bounty hunting: "The problem is when you go hunting, when you pull any type of numbers for a police officer to perform, we are gonna go to the most vulnerable. We're gonna go to the LGBT community, we're gonna go to the black community."

Progressive punishment isn't a universal panacea and won't fix the complex issues of mass incarceration or entrenched racism. But if combined with other smart policies - increasing income and property taxes in some places, reining in ticketing more generally, eliminating debtors' prisons, ending for-profit policing, creating real community oversight and so on - it could be part of the solution to some of the problems recent tragedies have exposed.

Making it possible to issue bigger tickets for people at the top of the income hierarchy might shift police incentives and help end the government-led shakedown of the poor that is currently ruining - and ending - lives.

This piece was supported by Economic Hardship Reporting Project.

Soon after the horrific video of Minneapolis-St Paul resident Philando Castile being killed by a cop during a routine traffic stop was broadcast live over Facebook, evidence of just how "routine" the stop actually was also became public.

Castile, it turned out, had been pulled over at least 52 times in 13 years for a variety of minor infractions - a broken seat belt, an unlit license plate, tinted windows, a missing muffler - or what his mother called "driving while black".

Across the country, cash-strapped courts squeeze money in the form of fines and fees from the very citizens who can least afford them. Over the course of those 13 years, Castile was charged over $6,500. And too often, when people can't pay, they wind up jail - sometimes for fines associated with things as trivial as a missing trash can lid or illegally parking - which is why advocates now talk about the "criminalization of poverty" and the return of "debtors' prisons".

Municipal budgets are overly reliant on petty infraction penalties because affluent, mostly white citizens have been engaged in a "tax revolt" for decades, lobbying for lower rates and special treatment.

This cycle has to be broken.

Some civic-minded lawyers are successfully bringing class-action suits in various states to halt unfair practices at the municipal level, including excess fines and fees and the use of for-profit probation services, while also arguing that jailing debtors is unconstitutional. As a consequence of these efforts, Jennings, Missouri recently settled to pay nearly $5m to 2,000 citizens who were locked up for unpaid court debts.

But in addition to lawsuits to help protect the poor, the rich must start pulling their weight. We need to fine people more the richer they are - penalties should be proportionate to income, not flat-rate. After all, a $200 sanction means a hell of a lot more to a single parent making minimum wage than to an executive raking in a six- or seven-figure income. Maybe the former should pay only $20, the latter $2,000 or even $20,000.

That's how many other countries do it. Finland, Switzerland, Sweden, Denmark, Germany, Austria and France all have some form of sliding-scale fines in place for offenses ranging from traffic tickets to petty theft and assault.

Every few years, there are news stories reporting on exotic, exorbitant European speeding tickets. There was the Finnish businessman who was hit with one for EUR54,024 (about $60,000) last spring for driving 64mph in a 50mph zone, or the Ferrari-driving Swiss repeat offender who made headlines with a record fine of PS182,000 (about $237,000). Such colossal fines are rare, but penalties calculated according to earnings are commonplace.

"This is a Nordic tradition," a Finnish government adviser told the Wall Street Journal over a decade ago, explaining principles that have been in place since the 1920s. "We have progressive taxation and progressive punishments. So the more you earn, the more you pay."

In the US, we still have progressive taxation, at least until Ted Cruz gets his way and institutes a flat tax. Now we need progressive punishment to match. Back in the 80s the National Institute of Justice supported pilot programs involving sliding-scale fines in Staten Island and Milwaukee. The idea didn't catch on, despite (or perhaps because of) the fact that the results were promising (in Milwaukee overall revenue went down, pegged as it was to mostly low-income defendants' ability to pay; in Staten Island, a combination of proportional fines and new collection practices led to a fewer arrest warrants related to nonpayment). But today, thanks to the effective work of the Black Lives Matter movement, the public is far more aware - and outraged - about the inequities of criminal justice system and may be more open to new approaches.

Some might object that progressive punishment would lead to police unfairly targeting the wealthy. One can imagine officers lying in wait for a juicy Porsche or Tesla to race by (which might actually be a boon to public safety, since studies have linked bad driving and increased wealth).

But such an image belittles the reality many communities of color and low-income people already face. A recent ACLU report on policing in Castile's home of Minneapolis found that black people are 8.7 times more likely than their white counterparts to be arrested for low-level offenses. Or, as NYPD officer Derick Waller told NBC this spring, comparing arrest quotas to bounty hunting: "The problem is when you go hunting, when you pull any type of numbers for a police officer to perform, we are gonna go to the most vulnerable. We're gonna go to the LGBT community, we're gonna go to the black community."

Progressive punishment isn't a universal panacea and won't fix the complex issues of mass incarceration or entrenched racism. But if combined with other smart policies - increasing income and property taxes in some places, reining in ticketing more generally, eliminating debtors' prisons, ending for-profit policing, creating real community oversight and so on - it could be part of the solution to some of the problems recent tragedies have exposed.

Making it possible to issue bigger tickets for people at the top of the income hierarchy might shift police incentives and help end the government-led shakedown of the poor that is currently ruining - and ending - lives.

This piece was supported by Economic Hardship Reporting Project.