Loudoun County is a suburban area with colonial roots, nestled about 45 miles northwest of the District of Columbia. It boasts the nation's highest median household income at nearly $124,000 per year. It also has 14,000 residents who struggle with food insecurity, or a lack of reliable access to affordable and nutritious food.

Elizabeth and her daughter, Jennifer, are Loudon County residents that struggle with hunger. Both women once had full-time jobs, but Elizabeth was let go from her job as a car mechanic when she injured her wrist. Then, Jennifer had to quit her job to help care for Elizabeth's four-year-old daughter.

Elizabeth and Jennifer's story is far from unique. Life is equally tough for Donna of Washington County, Maine. In an effort to feed herself, the 77-year-old grows vegetables when weather permits but she still has difficulty covering her bills and buying food. And in Bartlett, Texas, Stephen, his wife Victoria, and their 4-year-old son face a similar struggle. For a time, Stephen says, the family was "living the American dream" in a 3-bedroom house with a 2-car garage. But when Victoria's mother developed Parkinson's, the family moved from Lubbock to Bartlett to care for her. The cost of the move consumed their life savings. While Stephen hunted for another job, he and Victoria relied on a food pantry about 25 miles away for regular meals.

Food insecurity exists in every county across the country

The U.S. Department of Agriculture reports that more than 48 million people in America--including 15 million children--are food-insecure. In April, Feeding America released new research that proves that this is not an isolated problem: food insecurity exists in every county in the United States.

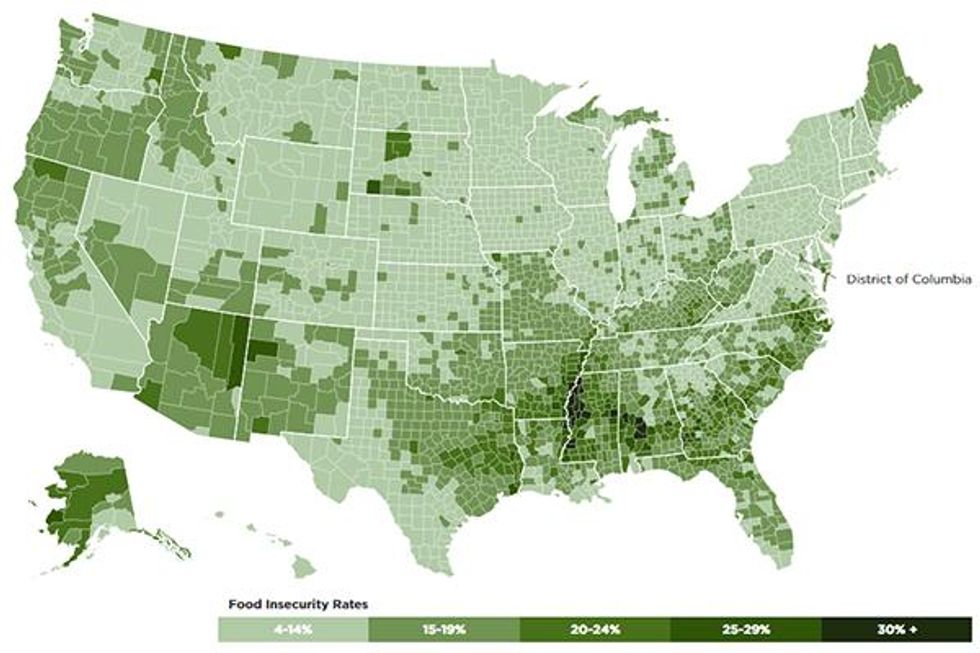

For six consecutive years, we've conducted a comprehensive study called Map the Meal Gap to improve our understanding of hunger and to fight food insecurity at the local, regional, and national levels. Our most recent analysis shows hunger's vast reach. On average, the food-insecurity rate among the nation's 3,142 counties is a staggering 14.7 percent (and the numbers are even higher for children). Food insecurity ranged from a high of 38 percent in Jefferson County, Mississippi to a low of 4 percent in Loudoun County, Virginia.

Percentage of individuals per county who are food insecure (Source: Feeding America)

Percentage of individuals per county who are food insecure (Source: Feeding America)

But these numbers don't tell the whole story. As Elizabeth, Donna, and Stephen's experiences suggest, a complex relationship exists between food insecurity and multiple, interconnected factors like unemployment, poverty, and income.

Unemployment drives hunger and poverty

Unemployment is the primary driver of food insecurity. The average unemployment rate across all counties was 6.3 percent in 2014, compared to an average of 9.2 percent among the top 10 percent of counties with the highest food-insecurity rates. We also found that the unemployment rate had a statistically significant effect on the rate of food insecurity, a relationship supported by the academic literature. Simply put, without income that comes from a job, people often lack the resources to purchase an adequate amount of food.

Hunger, poverty, and federal programs

According to the USDA there are 353 counties struggling with "persistent poverty," where at least one-fifth of the population has been living in poverty for 30 years. There is also a significant overlap between these counties and those that fall into the top 10 percent for food insecurity nationwide: of the latter, nearly two-thirds suffer from persistent-poverty.

Moreover, hardship doesn't necessarily stop once someone is above the income eligibility threshold for federal nutrition assistance. In fact, there is considerable food insecurity among families that are ineligible for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP): More than one-fourth of all food-insecure people live in households with incomes above 185 percent of the poverty level, and thus are ineligible for federal food assistance programs.

Consider a man trying to recover from a job loss or a medical emergency that plunged his family into hardship. Over time he cobbles together a number of part-time jobs. A local food agency provides nutritious meals and even helps enroll him and his family in federal assistance programs. Through hard work and frugality, the family saves $10 to $15 every month. They slowly approach self-sufficiency, a precarious tipping point in which they'll either slide back into poverty or move forward with their lives. At that very moment, certain federal programs halt because they've reached the income threshold.

Earning too much and not enough

Among all people struggling with hunger in the U.S., more than half--56 percent--have incomes above the federal poverty level.

There are now 115 counties where the majority of food-insecure individuals are likely ineligible for most federal nutrition assistance programs based on their household income. Beyond the help of friends and relatives, charitable organizations are often the primary resource available to them. My organization, Feeding America, serves some 46.5 million people annually through a nationwide network of 200 food banks and 60,000 food pantries and meal programs. But we cannot address hunger without strong federal nutrition programs.

Even after the end of the Great Recession, we continue to witness historically high levels of food insecurity. Many stories illustrate the complicated circumstances that push people into a state of food insecurity and, in many cases, anchor them there for years. But by working together and implementing data-driven solutions, we can move closer to creating a hunger-free America.