SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

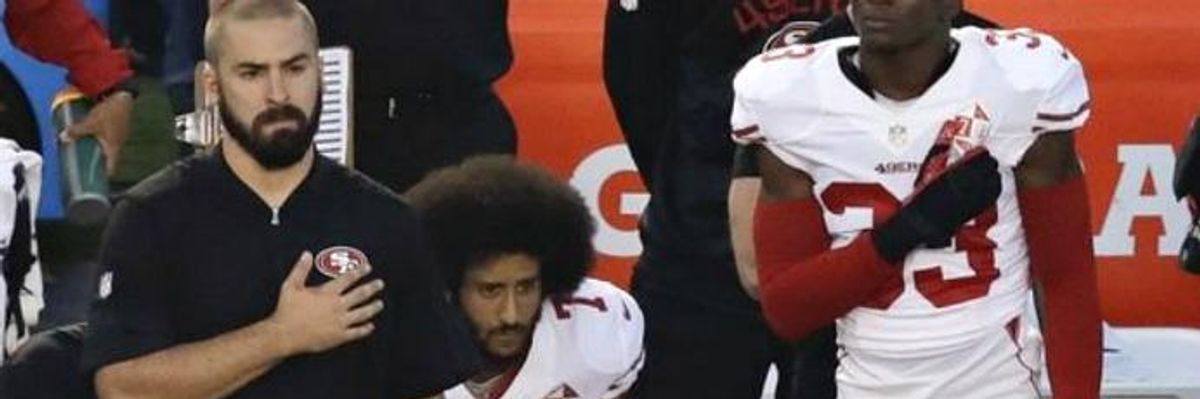

San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick kneels while others stand during the playing of the National Anthem at a preseason game.

It was my own moment of reckoning--stand and salute for the Star Spangled Banner or sit? The moment returns in memory, brought back by the current flap involving Colin Kaepernick's refusal to stand for the National Anthem. Kaepernick is a quarterback for the San Francisco 49ers football team who did not stand for the playing of the Star Spangled Banner before the start of the 49ers August 26 game against the Green Bay Packers. The next week vs. the San Diego Chargers, he sat again.

My own first protest sit-down made was indelibly set--Fort Lewis Army Base in February, 1970--and the stakes--retention in the Army as a draftee, if not reassignment to Vietnam etched it in memory. But back to the Kaepernick story.

Kaepernick says he is "not going to stand up and show support for a country that oppresses black people and people of color." The reaction to his protest has been mixed with most, and the loudest, voices expressing opposition. Kaepernick's supporters are fewer in number but count among themselves some fellow athletes.

Curiously though, both camps invoke the memory of war veterans to bolster their positions. Against Kaepernick's action, retired Colonel James Zumwalt called the sit-down, "a slap in the face to others of all ethnicities who only wish they could, once again, stand as it is played--our courageous veterans whose battlefield wounds have left them legless to do so." CNN found other critics of Kaepernick citing veteran sacrifices to support their views, while still others, quoted in the same link, support the QB on the grounds that veterans fought for his exercise of free speech.

With many voices using veterans to support their cases, pro and con, on Kaepernick's action, it was a relief to find an article actually written by a veteran in support of his protest. In the article currently posted at Jacobin, veteran Rory Fanning captures the inspiration that Kaepernick provides for veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan.Fanning especially appreciates the risks to career and reputation that the 49ers star is taking, and describes his own apprehension when not standing for the National Anthem in support of Kaepernick.

I support the position that Kaepernick has taken and I'm glad to hear veterans' voices like Fanning's that counterbalance the exploitation of veteran identity for what I think is kneejerk patriotism; the courage shown by Fanning for conducting his own sympathy sit-down is especially laudable. But recognition of veterans who support quarterback Kaepernick and even demonstrate their solidarity as Fanning has done, still leaves a gap in the national discourse about veterans, patriotism, and symbols like the National Anthem, a gap that can be narrowed with some historical perspective.

It would surprise no one that not standing for the National Anthem was a common act of protest against the war in Vietnam in the late 1960s and early 1970s. And given the tenor of the times--during which some veterans joined the movement against the war--veterans' support for the sitters was not uncommon. But what has been largely washed out of American memory about the war years is that veterans not only supported the protesters, as Fanning has done, but enacted their own refusals to stand in dissent from their own war and the part they played in it--it was their cause that sat for, not someone else's or someone else's protest that the veterans supported.

But there is more to the story. Even while still in uniform, and with consequences way more dire than public disdain at stake, some soldiers were defying military authority. My own gut-check came when I rotated back to the States from Vietnam in 1970. Resistance to the military authority and the war was rife within the ranks by then. Observing the stateside Moratorium Days against the War in the fall of 1969, many of us could not wait to return home and join the Movement. Some didn't wait--some field units refused patrol assignments in support of the Moratorium, while other wore black armbands to show their solidarity with the protesters back home. The sabotage of operations was not uncommon by that time and actual attempts to kill officers and NCOs were frequent enough to unsettle commanders. Some of that history is documented in the 2006 film Sir! No Sir! about in-service dissent during the war,

Contra the shibboleth that we were in Vietnam to "fight for the flag," the common retort was that we were there "because of the flag!"--the meaning being that it was mindless patriotism that had put our lives and limbs at risk on the wrong side of a war that we were destined to lose. Commitments to "never stand for the flag again"--sometimes made promiscuously with the machismo-enhancement of good weed, for sure--were virtual credential checks of the warriors-against-the-war we were expected to have become.

By my date to return to the states, word had trickled back from those who had gone before about the logistics of processing-out for flights home and the procedures that awaited us when we landed in the states. Contrary to the myths popularized years later that we were warned about the spitting hippies awaiting us (there were no such warnings), some of us actually hoped to be greeted by anti-war activists hoping to sign us up--that didn't happen either (as far as I know). What did give us pause were reports that we would have to stand one last time at the out-processing center and sing the National Anthem. In the resistance-rich culture we were leaving, the declarations of "No way!" and "Ain't gonna happen!" were easy to make; separated from those peers after a long flight from Vietnam, glad to be home in one piece, and looking forward to reunions with family and friends, the talk was not so easy to walk.

I landed at McCord Airforce Base near Seattle and was taken from there to nearby Ft. Lewis for processing. After a meal and the completion of paperwork, I was ushered with a group of 10 to 20 other returnees, none of whom had ever met, into a small room where we were told, in military fashion, that upon command we WOULD come to attention and WOULD salute/pledge/sing (whatever) in accordance with whatever followed.

For me it was a time of reckoning. I had never done anything more political than vote before being drafted and in Vietnam I had participated in only low levels of dissent--whistle blowing on higher-ups, and work slowdown types of things. My one brush with the military justice system had been scary; the capriciousness and the callousness of its administrators was breathtaking. Rumors abounded among enlisted personnel that military authorities were cracking down on dissent. My father had died just before I was inducted in 1968 leaving my mother alone in a small town in Iowa, albeit surrounded by neighbors and family; she was not political at all and would never understand my choice to dissent rather than come home. Would failure to stand, salute, and sing result in a courts-martial? Could I be held at Ft. Lewis for legal prosecution? Even incarcerated? Could I be sent back to Vietnam? The questions flooded my mind.

Being seated in the small room, we were thanked for our service and then, yes, told to stand and salute. In the split second I had for making a decision, not a muscle moved--not mine or, I sensed, anyone else's. The entire room, excepting the officer in charge, stayed sitting. Without missing a beat--suggesting this had become routine for him--the officer moved along as if all was normal, hitting the play button for the National Anthem--and we sat.

It was an empowering moment for me. To have taken what, in the moment, appeared to be a huge risk with my own freedom and needs of my mother, and see that others, who were perfect strangers, were taking the same risk was reassuring, a real reality check validating my own experience. More importantly, I overcome my own fears of recrimination, fear that I might look "too radical," or being stigmatized for nonconformity. It was my own test-of-self and I had passed.

In the midst of the Kaepernick affair, news reports are telling us quite a lot about the history of the National Anthem in sporting events. I'm quite sure the Anthem was not part of my high school sports scene in the 1950s and I don't recall it being played at my college games in the 1960s. After the war in Vietnam I remember sitting for the Anthem on various occasions but that was a widespread practice at the time. I was shocked then when attending an Iowa-Wisconsin basketball game in Madison in the mid-80s to be one of the few fans staying seated while it played. Madison--cradle of the Movement!

But times had changed. It was the Reagan era and we learned from Rambo that we had lost the war in Vietnam because "somebody wouldn't let us win," that POWs had been left behind, and that veterans had been spat on. Lost in that mythology of home-front betrayal was the history that thousands of troops in Vietnam and veterans upon return had joined in resisting the war and help end it.

It takes courage for Kaepernick to do what he is doing and for Fanning and the rest of us to sit with him. It helps to know that we are not alone when we defy social conventions for good reasons. It helps, additionally, to know that others have done it before, and that for that we need to recover the lost themes of history--like soldiers and veterans who embraced dissent in behalf of their own values despite great risk to themselves. It is a call for historians to help fill those gaps in public memory and for veterans themselves who "took a knee" for peace to speak up.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

It was my own moment of reckoning--stand and salute for the Star Spangled Banner or sit? The moment returns in memory, brought back by the current flap involving Colin Kaepernick's refusal to stand for the National Anthem. Kaepernick is a quarterback for the San Francisco 49ers football team who did not stand for the playing of the Star Spangled Banner before the start of the 49ers August 26 game against the Green Bay Packers. The next week vs. the San Diego Chargers, he sat again.

My own first protest sit-down made was indelibly set--Fort Lewis Army Base in February, 1970--and the stakes--retention in the Army as a draftee, if not reassignment to Vietnam etched it in memory. But back to the Kaepernick story.

Kaepernick says he is "not going to stand up and show support for a country that oppresses black people and people of color." The reaction to his protest has been mixed with most, and the loudest, voices expressing opposition. Kaepernick's supporters are fewer in number but count among themselves some fellow athletes.

Curiously though, both camps invoke the memory of war veterans to bolster their positions. Against Kaepernick's action, retired Colonel James Zumwalt called the sit-down, "a slap in the face to others of all ethnicities who only wish they could, once again, stand as it is played--our courageous veterans whose battlefield wounds have left them legless to do so." CNN found other critics of Kaepernick citing veteran sacrifices to support their views, while still others, quoted in the same link, support the QB on the grounds that veterans fought for his exercise of free speech.

With many voices using veterans to support their cases, pro and con, on Kaepernick's action, it was a relief to find an article actually written by a veteran in support of his protest. In the article currently posted at Jacobin, veteran Rory Fanning captures the inspiration that Kaepernick provides for veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan.Fanning especially appreciates the risks to career and reputation that the 49ers star is taking, and describes his own apprehension when not standing for the National Anthem in support of Kaepernick.

I support the position that Kaepernick has taken and I'm glad to hear veterans' voices like Fanning's that counterbalance the exploitation of veteran identity for what I think is kneejerk patriotism; the courage shown by Fanning for conducting his own sympathy sit-down is especially laudable. But recognition of veterans who support quarterback Kaepernick and even demonstrate their solidarity as Fanning has done, still leaves a gap in the national discourse about veterans, patriotism, and symbols like the National Anthem, a gap that can be narrowed with some historical perspective.

It would surprise no one that not standing for the National Anthem was a common act of protest against the war in Vietnam in the late 1960s and early 1970s. And given the tenor of the times--during which some veterans joined the movement against the war--veterans' support for the sitters was not uncommon. But what has been largely washed out of American memory about the war years is that veterans not only supported the protesters, as Fanning has done, but enacted their own refusals to stand in dissent from their own war and the part they played in it--it was their cause that sat for, not someone else's or someone else's protest that the veterans supported.

But there is more to the story. Even while still in uniform, and with consequences way more dire than public disdain at stake, some soldiers were defying military authority. My own gut-check came when I rotated back to the States from Vietnam in 1970. Resistance to the military authority and the war was rife within the ranks by then. Observing the stateside Moratorium Days against the War in the fall of 1969, many of us could not wait to return home and join the Movement. Some didn't wait--some field units refused patrol assignments in support of the Moratorium, while other wore black armbands to show their solidarity with the protesters back home. The sabotage of operations was not uncommon by that time and actual attempts to kill officers and NCOs were frequent enough to unsettle commanders. Some of that history is documented in the 2006 film Sir! No Sir! about in-service dissent during the war,

Contra the shibboleth that we were in Vietnam to "fight for the flag," the common retort was that we were there "because of the flag!"--the meaning being that it was mindless patriotism that had put our lives and limbs at risk on the wrong side of a war that we were destined to lose. Commitments to "never stand for the flag again"--sometimes made promiscuously with the machismo-enhancement of good weed, for sure--were virtual credential checks of the warriors-against-the-war we were expected to have become.

By my date to return to the states, word had trickled back from those who had gone before about the logistics of processing-out for flights home and the procedures that awaited us when we landed in the states. Contrary to the myths popularized years later that we were warned about the spitting hippies awaiting us (there were no such warnings), some of us actually hoped to be greeted by anti-war activists hoping to sign us up--that didn't happen either (as far as I know). What did give us pause were reports that we would have to stand one last time at the out-processing center and sing the National Anthem. In the resistance-rich culture we were leaving, the declarations of "No way!" and "Ain't gonna happen!" were easy to make; separated from those peers after a long flight from Vietnam, glad to be home in one piece, and looking forward to reunions with family and friends, the talk was not so easy to walk.

I landed at McCord Airforce Base near Seattle and was taken from there to nearby Ft. Lewis for processing. After a meal and the completion of paperwork, I was ushered with a group of 10 to 20 other returnees, none of whom had ever met, into a small room where we were told, in military fashion, that upon command we WOULD come to attention and WOULD salute/pledge/sing (whatever) in accordance with whatever followed.

For me it was a time of reckoning. I had never done anything more political than vote before being drafted and in Vietnam I had participated in only low levels of dissent--whistle blowing on higher-ups, and work slowdown types of things. My one brush with the military justice system had been scary; the capriciousness and the callousness of its administrators was breathtaking. Rumors abounded among enlisted personnel that military authorities were cracking down on dissent. My father had died just before I was inducted in 1968 leaving my mother alone in a small town in Iowa, albeit surrounded by neighbors and family; she was not political at all and would never understand my choice to dissent rather than come home. Would failure to stand, salute, and sing result in a courts-martial? Could I be held at Ft. Lewis for legal prosecution? Even incarcerated? Could I be sent back to Vietnam? The questions flooded my mind.

Being seated in the small room, we were thanked for our service and then, yes, told to stand and salute. In the split second I had for making a decision, not a muscle moved--not mine or, I sensed, anyone else's. The entire room, excepting the officer in charge, stayed sitting. Without missing a beat--suggesting this had become routine for him--the officer moved along as if all was normal, hitting the play button for the National Anthem--and we sat.

It was an empowering moment for me. To have taken what, in the moment, appeared to be a huge risk with my own freedom and needs of my mother, and see that others, who were perfect strangers, were taking the same risk was reassuring, a real reality check validating my own experience. More importantly, I overcome my own fears of recrimination, fear that I might look "too radical," or being stigmatized for nonconformity. It was my own test-of-self and I had passed.

In the midst of the Kaepernick affair, news reports are telling us quite a lot about the history of the National Anthem in sporting events. I'm quite sure the Anthem was not part of my high school sports scene in the 1950s and I don't recall it being played at my college games in the 1960s. After the war in Vietnam I remember sitting for the Anthem on various occasions but that was a widespread practice at the time. I was shocked then when attending an Iowa-Wisconsin basketball game in Madison in the mid-80s to be one of the few fans staying seated while it played. Madison--cradle of the Movement!

But times had changed. It was the Reagan era and we learned from Rambo that we had lost the war in Vietnam because "somebody wouldn't let us win," that POWs had been left behind, and that veterans had been spat on. Lost in that mythology of home-front betrayal was the history that thousands of troops in Vietnam and veterans upon return had joined in resisting the war and help end it.

It takes courage for Kaepernick to do what he is doing and for Fanning and the rest of us to sit with him. It helps to know that we are not alone when we defy social conventions for good reasons. It helps, additionally, to know that others have done it before, and that for that we need to recover the lost themes of history--like soldiers and veterans who embraced dissent in behalf of their own values despite great risk to themselves. It is a call for historians to help fill those gaps in public memory and for veterans themselves who "took a knee" for peace to speak up.

It was my own moment of reckoning--stand and salute for the Star Spangled Banner or sit? The moment returns in memory, brought back by the current flap involving Colin Kaepernick's refusal to stand for the National Anthem. Kaepernick is a quarterback for the San Francisco 49ers football team who did not stand for the playing of the Star Spangled Banner before the start of the 49ers August 26 game against the Green Bay Packers. The next week vs. the San Diego Chargers, he sat again.

My own first protest sit-down made was indelibly set--Fort Lewis Army Base in February, 1970--and the stakes--retention in the Army as a draftee, if not reassignment to Vietnam etched it in memory. But back to the Kaepernick story.

Kaepernick says he is "not going to stand up and show support for a country that oppresses black people and people of color." The reaction to his protest has been mixed with most, and the loudest, voices expressing opposition. Kaepernick's supporters are fewer in number but count among themselves some fellow athletes.

Curiously though, both camps invoke the memory of war veterans to bolster their positions. Against Kaepernick's action, retired Colonel James Zumwalt called the sit-down, "a slap in the face to others of all ethnicities who only wish they could, once again, stand as it is played--our courageous veterans whose battlefield wounds have left them legless to do so." CNN found other critics of Kaepernick citing veteran sacrifices to support their views, while still others, quoted in the same link, support the QB on the grounds that veterans fought for his exercise of free speech.

With many voices using veterans to support their cases, pro and con, on Kaepernick's action, it was a relief to find an article actually written by a veteran in support of his protest. In the article currently posted at Jacobin, veteran Rory Fanning captures the inspiration that Kaepernick provides for veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan.Fanning especially appreciates the risks to career and reputation that the 49ers star is taking, and describes his own apprehension when not standing for the National Anthem in support of Kaepernick.

I support the position that Kaepernick has taken and I'm glad to hear veterans' voices like Fanning's that counterbalance the exploitation of veteran identity for what I think is kneejerk patriotism; the courage shown by Fanning for conducting his own sympathy sit-down is especially laudable. But recognition of veterans who support quarterback Kaepernick and even demonstrate their solidarity as Fanning has done, still leaves a gap in the national discourse about veterans, patriotism, and symbols like the National Anthem, a gap that can be narrowed with some historical perspective.

It would surprise no one that not standing for the National Anthem was a common act of protest against the war in Vietnam in the late 1960s and early 1970s. And given the tenor of the times--during which some veterans joined the movement against the war--veterans' support for the sitters was not uncommon. But what has been largely washed out of American memory about the war years is that veterans not only supported the protesters, as Fanning has done, but enacted their own refusals to stand in dissent from their own war and the part they played in it--it was their cause that sat for, not someone else's or someone else's protest that the veterans supported.

But there is more to the story. Even while still in uniform, and with consequences way more dire than public disdain at stake, some soldiers were defying military authority. My own gut-check came when I rotated back to the States from Vietnam in 1970. Resistance to the military authority and the war was rife within the ranks by then. Observing the stateside Moratorium Days against the War in the fall of 1969, many of us could not wait to return home and join the Movement. Some didn't wait--some field units refused patrol assignments in support of the Moratorium, while other wore black armbands to show their solidarity with the protesters back home. The sabotage of operations was not uncommon by that time and actual attempts to kill officers and NCOs were frequent enough to unsettle commanders. Some of that history is documented in the 2006 film Sir! No Sir! about in-service dissent during the war,

Contra the shibboleth that we were in Vietnam to "fight for the flag," the common retort was that we were there "because of the flag!"--the meaning being that it was mindless patriotism that had put our lives and limbs at risk on the wrong side of a war that we were destined to lose. Commitments to "never stand for the flag again"--sometimes made promiscuously with the machismo-enhancement of good weed, for sure--were virtual credential checks of the warriors-against-the-war we were expected to have become.

By my date to return to the states, word had trickled back from those who had gone before about the logistics of processing-out for flights home and the procedures that awaited us when we landed in the states. Contrary to the myths popularized years later that we were warned about the spitting hippies awaiting us (there were no such warnings), some of us actually hoped to be greeted by anti-war activists hoping to sign us up--that didn't happen either (as far as I know). What did give us pause were reports that we would have to stand one last time at the out-processing center and sing the National Anthem. In the resistance-rich culture we were leaving, the declarations of "No way!" and "Ain't gonna happen!" were easy to make; separated from those peers after a long flight from Vietnam, glad to be home in one piece, and looking forward to reunions with family and friends, the talk was not so easy to walk.

I landed at McCord Airforce Base near Seattle and was taken from there to nearby Ft. Lewis for processing. After a meal and the completion of paperwork, I was ushered with a group of 10 to 20 other returnees, none of whom had ever met, into a small room where we were told, in military fashion, that upon command we WOULD come to attention and WOULD salute/pledge/sing (whatever) in accordance with whatever followed.

For me it was a time of reckoning. I had never done anything more political than vote before being drafted and in Vietnam I had participated in only low levels of dissent--whistle blowing on higher-ups, and work slowdown types of things. My one brush with the military justice system had been scary; the capriciousness and the callousness of its administrators was breathtaking. Rumors abounded among enlisted personnel that military authorities were cracking down on dissent. My father had died just before I was inducted in 1968 leaving my mother alone in a small town in Iowa, albeit surrounded by neighbors and family; she was not political at all and would never understand my choice to dissent rather than come home. Would failure to stand, salute, and sing result in a courts-martial? Could I be held at Ft. Lewis for legal prosecution? Even incarcerated? Could I be sent back to Vietnam? The questions flooded my mind.

Being seated in the small room, we were thanked for our service and then, yes, told to stand and salute. In the split second I had for making a decision, not a muscle moved--not mine or, I sensed, anyone else's. The entire room, excepting the officer in charge, stayed sitting. Without missing a beat--suggesting this had become routine for him--the officer moved along as if all was normal, hitting the play button for the National Anthem--and we sat.

It was an empowering moment for me. To have taken what, in the moment, appeared to be a huge risk with my own freedom and needs of my mother, and see that others, who were perfect strangers, were taking the same risk was reassuring, a real reality check validating my own experience. More importantly, I overcome my own fears of recrimination, fear that I might look "too radical," or being stigmatized for nonconformity. It was my own test-of-self and I had passed.

In the midst of the Kaepernick affair, news reports are telling us quite a lot about the history of the National Anthem in sporting events. I'm quite sure the Anthem was not part of my high school sports scene in the 1950s and I don't recall it being played at my college games in the 1960s. After the war in Vietnam I remember sitting for the Anthem on various occasions but that was a widespread practice at the time. I was shocked then when attending an Iowa-Wisconsin basketball game in Madison in the mid-80s to be one of the few fans staying seated while it played. Madison--cradle of the Movement!

But times had changed. It was the Reagan era and we learned from Rambo that we had lost the war in Vietnam because "somebody wouldn't let us win," that POWs had been left behind, and that veterans had been spat on. Lost in that mythology of home-front betrayal was the history that thousands of troops in Vietnam and veterans upon return had joined in resisting the war and help end it.

It takes courage for Kaepernick to do what he is doing and for Fanning and the rest of us to sit with him. It helps to know that we are not alone when we defy social conventions for good reasons. It helps, additionally, to know that others have done it before, and that for that we need to recover the lost themes of history--like soldiers and veterans who embraced dissent in behalf of their own values despite great risk to themselves. It is a call for historians to help fill those gaps in public memory and for veterans themselves who "took a knee" for peace to speak up.