SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

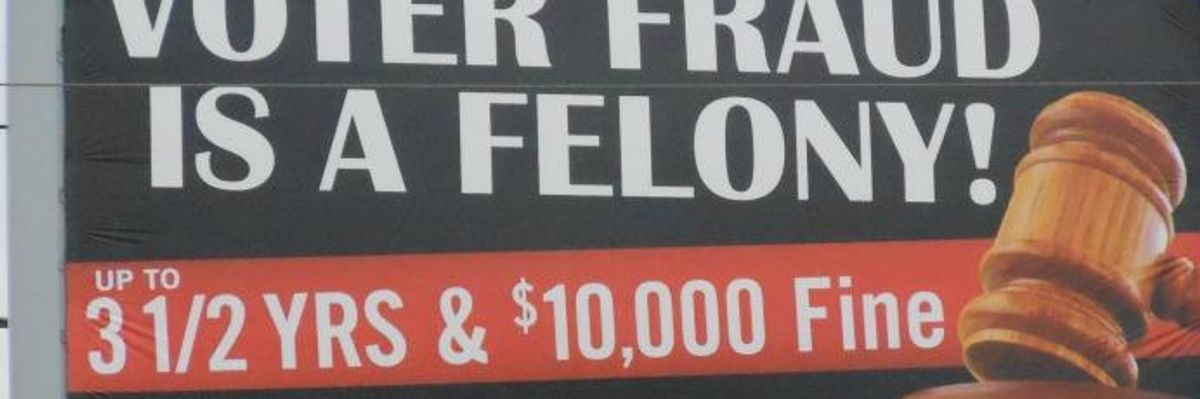

'Debunking the myth of pervasive voter fraud, like debunking the myth behind Barack Obama's foreign birth or the myth that global warming is a hoax,' writes Cohen, 'requires a level of journalistic commitment that few news outlets are able or willing to muster.' (Photo: Donkey Hotey)

One of the most distressing indications of failure in American journalism today is the release of a poll last week that reveals that nearly half of the country believes that voter fraud occurs "very or somewhat often." Since there is no rational basis in law or fact for this belief, since you are more likely to be struck

One of the most distressing indications of failure in American journalism today is the release of a poll last week that reveals that nearly half of the country believes that voter fraud occurs "very or somewhat often." Since there is no rational basis in law or fact for this belief, since you are more likely to be struck by lightning than to be a victim of in-person voter fraud, the poll results tell us that reporters, analysts, and commentators who try to cover this topic have failed to adequately explain to our audiences the contours of the myth of voter fraud or to highlight how the issue has been hijacked by one party to try to disenfranchise those likely to vote for the other party.

The poll results tell us that the scourge of "false equivalence" in reporting has infected this intensely-partisan policy area in the same way it has infected other areas. There is no "on the one hand, on the other hand" when it comes to the evidence about the sort of voter fraud that voter identification laws are supposedly designed to prevent. Just because Republican lawmakers in several states have passed these laws, and just because some conservative judges have upheld them, does not mean that the rationale supporting the legislation is legitimate. It is not, as the story of the voter ID law in Texas teaches us.

Nor is there a valid he said/she said divide when it comes to the arguments made by lawmakers to justify limiting early voting days or hours or restricting access to polling stations. The latest of these arguments made in North Carolina--that early voting is a menace because early voters could die between the time they cast a ballot and the day of the election--is laughable until you remember that absentee ballot fraud, a potentially far more serious problem, was left unaddressed by those same lawmakers. More white people vote by absentee ballot. More minority voters cast early ballots. That explains it all.

Debunking the myth of pervasive voter fraud, like debunking the myth behind Barack Obama's foreign birth or the myth that global warming is a hoax, requires a level of journalistic commitment that few news outlets are able or willing to muster. It requires, you could say, a chipping away with relentless evidence at people unable or unwilling to let facts interfere with their beliefs. It requires the victory of logic over fear, of evidence over bias, and today those victories seem harder than ever.

One would think that the U.S. Supreme Court's disastrous 2013 voting rights ruling in Shelby County v. Holder, and the way in which lawmakers in states like North Carolina and Texas immediately reacted to it, would have changed the dynamic of how this story has been reported. It has, a bit, but given these poll results clearly not enough to convince more Americans that they ought to be more afraid of Bigfoot or the Loch Ness monster than of voter fraud resulting in a stolen election. Ask 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals Judge Richard Posner, the appointee of Ronald Reagan, what he now thinks of laws designed to prevent voter fraud.

The failure is more pronounced now because the issue of voting rights, and disenfranchisement, could not be more vital this election season, the first presidential election since the five Republican justices then on the Court gutted the pre-clearance provision of the Voting Rights Act. That ruling means that, by partisan design, 50 years after passage of the Voting Rights Act, there will be fewer minority voters who are able to cast ballots in swing states like North Carolina, Ohio, and Wisconsin. Donald Trump knows this, of course, which is why he's been fanning the flames of the voter fraud myth.

The poll tells me, finally, that those who cover this story, and the advocates who strive to broaden voting rights for all, have failed to adequately address (for editors and cable show bookers anyway) a "talking point" that almost always is raised whenever the topic of voter ID laws, and voter suppression, is raised. "If you need photo identification to get cough medicine at a pharmacy why shouldn't you need photo identification to cast a ballot in an election?" It's an attractive question for perpetrators of the voter fraud myth, especially if you are fortunate enough to be able to afford a car and the driver's license that comes with it.

The answer is simple: "You do not have a legal right to be free from discrimination when you try to get cough medicine from your pharmacist. Your fellow Americans did not die in the 1950s and 1960s fighting for your right to get cough medicine from your pharmacist. Your state government is not trying to deprive you of your right to cough medicine because of the color of your skin. Congress did not pass a law, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and did not extend its provisions decade after decade until now, so that you could have a right to your cough medicine."

When one party is trying to keep eligible voters from voting, and the stated justification for such suppression is unsupported by fact, and the unstated justification for such suppression is rooted in the nation's history of racial bias, journalists have an ethical and moral obligation to say so every time the topic comes up. Such devotion to the truth may not change the poll numbers revealed last week. Clearly millions of Americans still are going to believe the voter fraud myth no matter how much of a fantasy it is. But at least the historians who judge this era in the history of journalism will look more kindly upon those reporters who tried to change the minds of their fellow citizens who on this topic are as certain as they are wrong.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

One of the most distressing indications of failure in American journalism today is the release of a poll last week that reveals that nearly half of the country believes that voter fraud occurs "very or somewhat often." Since there is no rational basis in law or fact for this belief, since you are more likely to be struck by lightning than to be a victim of in-person voter fraud, the poll results tell us that reporters, analysts, and commentators who try to cover this topic have failed to adequately explain to our audiences the contours of the myth of voter fraud or to highlight how the issue has been hijacked by one party to try to disenfranchise those likely to vote for the other party.

The poll results tell us that the scourge of "false equivalence" in reporting has infected this intensely-partisan policy area in the same way it has infected other areas. There is no "on the one hand, on the other hand" when it comes to the evidence about the sort of voter fraud that voter identification laws are supposedly designed to prevent. Just because Republican lawmakers in several states have passed these laws, and just because some conservative judges have upheld them, does not mean that the rationale supporting the legislation is legitimate. It is not, as the story of the voter ID law in Texas teaches us.

Nor is there a valid he said/she said divide when it comes to the arguments made by lawmakers to justify limiting early voting days or hours or restricting access to polling stations. The latest of these arguments made in North Carolina--that early voting is a menace because early voters could die between the time they cast a ballot and the day of the election--is laughable until you remember that absentee ballot fraud, a potentially far more serious problem, was left unaddressed by those same lawmakers. More white people vote by absentee ballot. More minority voters cast early ballots. That explains it all.

Debunking the myth of pervasive voter fraud, like debunking the myth behind Barack Obama's foreign birth or the myth that global warming is a hoax, requires a level of journalistic commitment that few news outlets are able or willing to muster. It requires, you could say, a chipping away with relentless evidence at people unable or unwilling to let facts interfere with their beliefs. It requires the victory of logic over fear, of evidence over bias, and today those victories seem harder than ever.

One would think that the U.S. Supreme Court's disastrous 2013 voting rights ruling in Shelby County v. Holder, and the way in which lawmakers in states like North Carolina and Texas immediately reacted to it, would have changed the dynamic of how this story has been reported. It has, a bit, but given these poll results clearly not enough to convince more Americans that they ought to be more afraid of Bigfoot or the Loch Ness monster than of voter fraud resulting in a stolen election. Ask 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals Judge Richard Posner, the appointee of Ronald Reagan, what he now thinks of laws designed to prevent voter fraud.

The failure is more pronounced now because the issue of voting rights, and disenfranchisement, could not be more vital this election season, the first presidential election since the five Republican justices then on the Court gutted the pre-clearance provision of the Voting Rights Act. That ruling means that, by partisan design, 50 years after passage of the Voting Rights Act, there will be fewer minority voters who are able to cast ballots in swing states like North Carolina, Ohio, and Wisconsin. Donald Trump knows this, of course, which is why he's been fanning the flames of the voter fraud myth.

The poll tells me, finally, that those who cover this story, and the advocates who strive to broaden voting rights for all, have failed to adequately address (for editors and cable show bookers anyway) a "talking point" that almost always is raised whenever the topic of voter ID laws, and voter suppression, is raised. "If you need photo identification to get cough medicine at a pharmacy why shouldn't you need photo identification to cast a ballot in an election?" It's an attractive question for perpetrators of the voter fraud myth, especially if you are fortunate enough to be able to afford a car and the driver's license that comes with it.

The answer is simple: "You do not have a legal right to be free from discrimination when you try to get cough medicine from your pharmacist. Your fellow Americans did not die in the 1950s and 1960s fighting for your right to get cough medicine from your pharmacist. Your state government is not trying to deprive you of your right to cough medicine because of the color of your skin. Congress did not pass a law, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and did not extend its provisions decade after decade until now, so that you could have a right to your cough medicine."

When one party is trying to keep eligible voters from voting, and the stated justification for such suppression is unsupported by fact, and the unstated justification for such suppression is rooted in the nation's history of racial bias, journalists have an ethical and moral obligation to say so every time the topic comes up. Such devotion to the truth may not change the poll numbers revealed last week. Clearly millions of Americans still are going to believe the voter fraud myth no matter how much of a fantasy it is. But at least the historians who judge this era in the history of journalism will look more kindly upon those reporters who tried to change the minds of their fellow citizens who on this topic are as certain as they are wrong.

One of the most distressing indications of failure in American journalism today is the release of a poll last week that reveals that nearly half of the country believes that voter fraud occurs "very or somewhat often." Since there is no rational basis in law or fact for this belief, since you are more likely to be struck by lightning than to be a victim of in-person voter fraud, the poll results tell us that reporters, analysts, and commentators who try to cover this topic have failed to adequately explain to our audiences the contours of the myth of voter fraud or to highlight how the issue has been hijacked by one party to try to disenfranchise those likely to vote for the other party.

The poll results tell us that the scourge of "false equivalence" in reporting has infected this intensely-partisan policy area in the same way it has infected other areas. There is no "on the one hand, on the other hand" when it comes to the evidence about the sort of voter fraud that voter identification laws are supposedly designed to prevent. Just because Republican lawmakers in several states have passed these laws, and just because some conservative judges have upheld them, does not mean that the rationale supporting the legislation is legitimate. It is not, as the story of the voter ID law in Texas teaches us.

Nor is there a valid he said/she said divide when it comes to the arguments made by lawmakers to justify limiting early voting days or hours or restricting access to polling stations. The latest of these arguments made in North Carolina--that early voting is a menace because early voters could die between the time they cast a ballot and the day of the election--is laughable until you remember that absentee ballot fraud, a potentially far more serious problem, was left unaddressed by those same lawmakers. More white people vote by absentee ballot. More minority voters cast early ballots. That explains it all.

Debunking the myth of pervasive voter fraud, like debunking the myth behind Barack Obama's foreign birth or the myth that global warming is a hoax, requires a level of journalistic commitment that few news outlets are able or willing to muster. It requires, you could say, a chipping away with relentless evidence at people unable or unwilling to let facts interfere with their beliefs. It requires the victory of logic over fear, of evidence over bias, and today those victories seem harder than ever.

One would think that the U.S. Supreme Court's disastrous 2013 voting rights ruling in Shelby County v. Holder, and the way in which lawmakers in states like North Carolina and Texas immediately reacted to it, would have changed the dynamic of how this story has been reported. It has, a bit, but given these poll results clearly not enough to convince more Americans that they ought to be more afraid of Bigfoot or the Loch Ness monster than of voter fraud resulting in a stolen election. Ask 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals Judge Richard Posner, the appointee of Ronald Reagan, what he now thinks of laws designed to prevent voter fraud.

The failure is more pronounced now because the issue of voting rights, and disenfranchisement, could not be more vital this election season, the first presidential election since the five Republican justices then on the Court gutted the pre-clearance provision of the Voting Rights Act. That ruling means that, by partisan design, 50 years after passage of the Voting Rights Act, there will be fewer minority voters who are able to cast ballots in swing states like North Carolina, Ohio, and Wisconsin. Donald Trump knows this, of course, which is why he's been fanning the flames of the voter fraud myth.

The poll tells me, finally, that those who cover this story, and the advocates who strive to broaden voting rights for all, have failed to adequately address (for editors and cable show bookers anyway) a "talking point" that almost always is raised whenever the topic of voter ID laws, and voter suppression, is raised. "If you need photo identification to get cough medicine at a pharmacy why shouldn't you need photo identification to cast a ballot in an election?" It's an attractive question for perpetrators of the voter fraud myth, especially if you are fortunate enough to be able to afford a car and the driver's license that comes with it.

The answer is simple: "You do not have a legal right to be free from discrimination when you try to get cough medicine from your pharmacist. Your fellow Americans did not die in the 1950s and 1960s fighting for your right to get cough medicine from your pharmacist. Your state government is not trying to deprive you of your right to cough medicine because of the color of your skin. Congress did not pass a law, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and did not extend its provisions decade after decade until now, so that you could have a right to your cough medicine."

When one party is trying to keep eligible voters from voting, and the stated justification for such suppression is unsupported by fact, and the unstated justification for such suppression is rooted in the nation's history of racial bias, journalists have an ethical and moral obligation to say so every time the topic comes up. Such devotion to the truth may not change the poll numbers revealed last week. Clearly millions of Americans still are going to believe the voter fraud myth no matter how much of a fantasy it is. But at least the historians who judge this era in the history of journalism will look more kindly upon those reporters who tried to change the minds of their fellow citizens who on this topic are as certain as they are wrong.