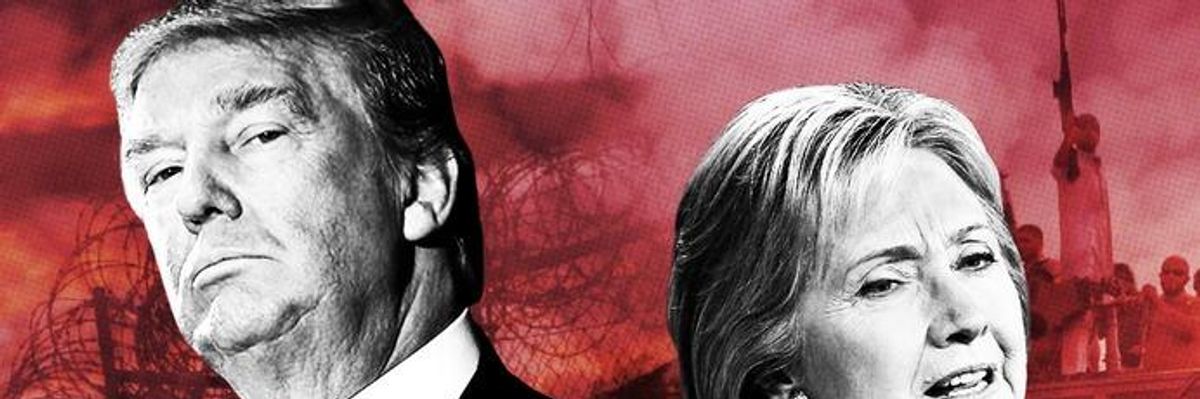

The media's tendency to focus on horserace issues--who's up and who's down, what the cosmetics are of an event rather than the substance--is routinely derided by media critics, and mocking it has become something of an election year tradition. But one 2016 topic in particular, terrorism, has become the hot horserace topic of the year in a way that goes beyond the silly to the potentially damaging:

- Clinton, Trump Jockey Over Who Would Best Fight Terrorists (WNBC, 9/20/16)

- Who Has the Upper Hand on Terrorism, Clinton or Trump? (Politico, 9/20/16)

- Terror Threat Clash: Trump, Clinton Accuse Each Other of Boosting Enemy (Fox News, 9/19/16)

- Clinton, Trump Spar Over Terrorism in Wake of Latest Attacks (USA Today, 9/20/16)

Something missing from these reports is any discussion of the relative danger of terrorism. The reporters begin with the premise that voters are afraid of it, never challenging the underlying rationality of those fears.

The reality is that terrorism remains, objectively, a very minor threat. (One is 82 times more likely to be killed falling out of bed than by a terrorist.) But by framing the issue as an urgent danger, with two candidates "dueling" over opposing ways of addressing this menace, the media further inflate terrorism's importance. Can one even imagine Trump and Clinton "jockeying" for position on climate change, or violence against women and LGBT communities, or lowering heart disease--all of which, statistically, are far, far more dangerous than terrorism?

This isn't a new problem, of course. In nine Democratic primary debates, for example, the moderators asked a total of 30 questions about terrorism or ISIS, and not one question about poverty (FAIR.org, 5/27/16). (A 2011 study by Columbia's school of public health estimated that 4.5 percent of all deaths in the United States are attributable to poverty.)

Polls show people are indeed increasingly worried about terrorism--and about "Islamic fundamentalism," with which it is often conflated in media discussions. (Republicans' fear of "Islamic fundamentalism" is now higher than immediately after 9/11.)

But such worries are fueled, at least in part, on the media's outsized coverage. Since 2006, according to the tabulations of USA Today, there have been 320 incidents of mass murder in the United States--incidents in which four or more people were killed, not including perpetrators. During that time, there have been five such attacks carried out by people apparently motivated by Islamicist ideology: the 2009 Fort Hood shooting, the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing, the 2015 Chattanooga shooting, the 2015 San Bernardino attack and the 2016 Orlando nightclub massacre. Two other mass murder incidents--the 2012 Wisconsin Sikh temple shooting and the 2015 Charleston church massacre--were carried out by right-wing extremists. These seven potentially terrorist attacks represent about 2 percent of the mass murder events in the United States over a little more than the last decade.

But media don't just cover terrorism, they engage in meta-terrorism--the terror that comes from the gratuitous or excessive coverage of stories that don't actually involve terrorism, but rather potential or staged terrorism, or ISIS propaganda repackaged as news. Note that in none of the following "terror" stories did any terrorism actually occur:

- Online Posts Show ISIS Eyeing Mexican Border, Says Law Enforcement Bulletin (Fox News, 8/24/14)

- FBI Director Comey: Several ISIS-Inspired July 4 Attacks Foiled (NBC, 7/9/15)

- Smugglers Busted Trying to Sell Nuclear Material to ISIS (AP, 10/7/15)

- ISIS Threatens NYC in New Propaganda Video (New York Post, 11/18/15)

- A Freeway Terror Attack Is the 'Nightmare We Worry About,' Law Enforcers Say (LA Times, 12/21/15)

- Feds: New York Man Was Planning ISIS Attack on New Year's Eve (CNN, 1/2/16)

- ISIS Planning 'Enormous and Spectacular Attacks,' Anti-Terror Chief Warns (Guardian, 3/7/16)

- ISIL Plotting to Use Drones for Nuclear Attack on West (Telegraph, 4/1/16)

- ISIS Nuclear Attack in Europe Is a Real Threat, Say Experts (Independent, 6/7/16)

The list could go on and on--with stories involving the FBI foiling terrorist "plots" of their own making, "experts" coming up with hypothetical terror attacks, or the outright dissemination of ISIS propaganda. The constant drum beat of meta-terror acts as an accelerator, taking each spark of actual terrorism and turning it into an inferno of panic.

The failure of those pieces on Trump and Clinton's "jockeying" for position on the issue of ISIS terrorism to note that the perception of fear does not equal the actual threat-that we are still far more likely to be harmed by dozens of other threats than terrorism--is in line with horserace journalism's prioritization of optics over substance, a phenomenon that's that much more toxic when dealing with a subject whose optics are skewed by racism and irrationality.

To the extent that there is any dampening of fears, it comes from the Clinton camp, in the context of countering Trump's brand of outright xenophobia. The Overton window has narrowed to a choice between overwrought ISIS panic and overwrought ISIS panic that's overtly racist.

Reporting that reached beyond the two campaigns' anti-ISIS talking points, and horserace analysis of their attempts to "out-position" each other, would serve the public by putting our fears of terrorism in perspective.