Political "divisions reach across every dimension of the climate debate," the Pew Research Center declared this week, releasing its latest survey results tracking polarization in the United States.

It's a bleakly familiar finding, but one that continues to generate a healthy amount of media coverage--including, reliably, calls to overcome the divide by giving climate messaging a right-wing makeover. One dogged proponent of this view is former Republican Congressman Bob Inglis, who suggested to the New York Times that talking about "greater independence, more mobility and more freedom" could somehow stamp out conservative denial. (It's not that hard to imagine this crowd arguing that we could flatter Trump into climate action.)

For a deeper look at the structure of U.S. public opinion on climate--and, crucially, the political implications--check out a fascinating study in the journal Environment that came out this summer (you can read it in full here). Sociologists Riley Dunlap, Aaron McCright, and Jerrod Yarosh put climate polarization in historical context, examining the trends in over the last couple decades or so. It's an update of previous work that Dunlap and McCright published in 2008; in that article, they had shown the partisan divide growing remarkably and rapidly during the George W. Bush years, and it's only intensified under Obama.

Take, for example, Gallup's polling on the question of whether warming is human-caused: "Democrats have always been more likely than Republicans to attribute global warming to human activities, starting with a relatively modest 17 percentage point difference in 2001 that grew to 32 by 2008. The partisan gap has fluctuated a fair amount since then, reaching 37 percentage points in 2010 and then 42 in 2013''--and "the gap remains very sizable."

On nearly all of Gallup's climate measures, the partisan divide has cracked open wider since 2008 (on just one question, it's remained constant):

In one of the most useful takeaways from the study, the authors have little patience for the notion that "more persuasive messaging" on climate--like re-framing it in conservative-friendly terms--is the solution:

Since the early 2000s, climate change communicators have increasingly advocated for, and often implemented, messaging strategies that attempt to frame climate change in ways expected to better resonate with the general public, and with key sectors such as conservatives. Dozens of studies have examined the effectiveness of these messaging and framing techniques. While several find these efforts to have no effect on Americans' climate change views, others do find a positive influence--but typically only a modest one at best. Yet almost none of these studies investigates how persuasive messages and frames perform in the presence of denial messages, which more closely approximates the reality of American media. The one study that does so finds that a denial message decreases citizens' belief in climate change, while potentially positive frames (e.g., economic opportunity, national security, etc.) have no effect. Further, some studies find that persuasion attempts may produce a "boomerang effect" among Republicans--actually eroding their concern about climate change. Does any persuasive framing strategy hold special promise for penetrating Republicans' partisan/ideological identities? The evidence so far gives little basis for optimism.

The latest Pew survey trumpets the fact that even most conservative Republicans support expanding solar power, a frequent source of hope for commentators. But as Dunlap, McCright, and Yarosh note in their paper, sociologists know that "individuals can hold relatively moderate positions on many issues and yet be strong partisans committed to keeping the other party out of office":

As long as rank-and-file Republicans vote for conservative candidates, and those candidates remain steadfast in opposition to climate change action, the former's receptivity to climate-friendly policies remains almost irrelevant--for the Congress they help elect will be highly unlikely to give such policies any consideration. Republican antipathy to governmental regulations, combined with enormous campaign contributions to the GOP from fossil fuel interests, means that most Republican politicians have strong ideological as well as material reasons for opposing measures to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, in addition to pressure from party activists and voters.

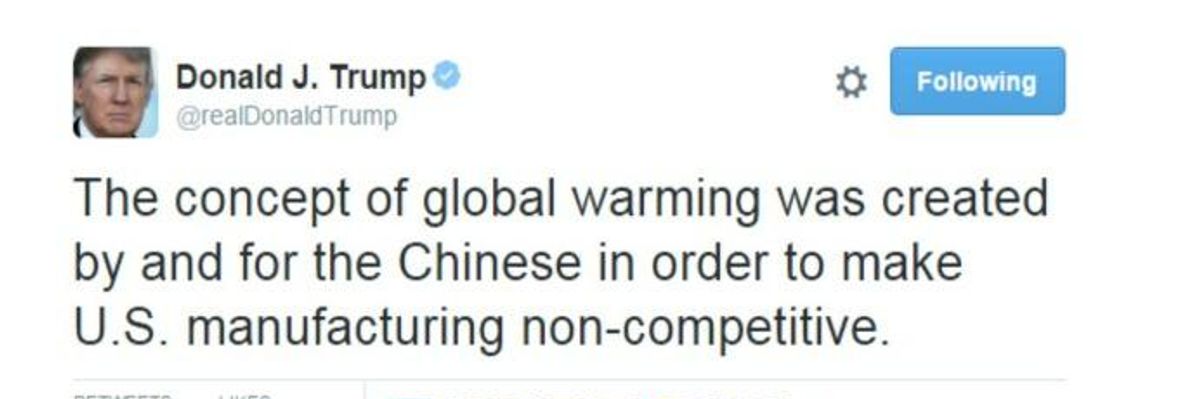

The key question is how these toxic dynamics get reproduced, and Dunlap and McCright have also done related, pioneering work on the "denial machine"--the nexus of fossil fuel companies, conservative foundations and think tanks, and political and media elites who have all, in various ways, driven the organized campaign to kill climate policy. Dunlap and McCright know how this stuff works, and they're blunt about what it means for next month's election.

"Unfortunately, the GOP has become a key cog in the 'denial machine,'" Dunlap told The Leap, "and its congressional leaders do everything possible to undermine climate science and block efforts to reduce carbon emissions. Citizens who recognize the serious threat posed by human-caused climate change are left with little option but to vote for Democratic candidates, as voting for a third party only increases the likelihood of a Trump Administration and Republican Congress dismantling climate change treaties and policies."

Dunlap adds: "Some people think it's important to back the small number Republican members of Congress who hold 'reasonable views' on climate change, like Kelly Ayotte of New Hampshire. The problem with this strategy is that she will help ensure that Mitch McConnell remains Senate Majority Leader, and that means continued obstruction of any effort to deal with climate change. The same holds true for the House of Representatives."

The Environment paper concludes with the sobering observation that "whether, and how, individual Americans vote this November may well be the most consequential climate-related decision most of them will have ever taken." Indeed--but as our time window to mobilize around transformative climate action dwindles rapidly, it's the job of social movements to make sure that doesn't stay true for long. With the recent revelation that existing coal, oil, and gas developments alone are enough to blow through the 2 degree target enshrined in the Paris deal, it's clearer than ever that by supporting fossil fuel expansion, Democrats are failing in their own way to face climate reality. After stopping Trump, the decisive organizing moment begins.