Next month, President-elect Trump will be handed the keys to the NSA's vast spying apparatus. As a candidate, he supported mass surveillance of Americans' phone calls, called for expanded spying on American Muslims, and even invited Russia to hack the emails of his political opponent. With these threats to privacy and liberty on the horizon, our courts will likely be more important than ever as a bulwark against unlawful spying.

One of the courtroom battles that will shape President-elect Trump's spying powers is already underway.

On Thursday, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals will hear oral argument in Wikimedia v. NSA, our case challenging "Upstream" surveillance. First revealed by whistleblower Edward Snowden in June 2013, Upstream surveillance involves the NSA's bulk searching of Americans' international internet communications with the assistance of companies like AT&T and Verizon. If you email friends abroad, chat with family members overseas, or browse websites hosted outside of the United States, the NSA has almost certainly searched through the contents of your communications -- and it has done so without a warrant.

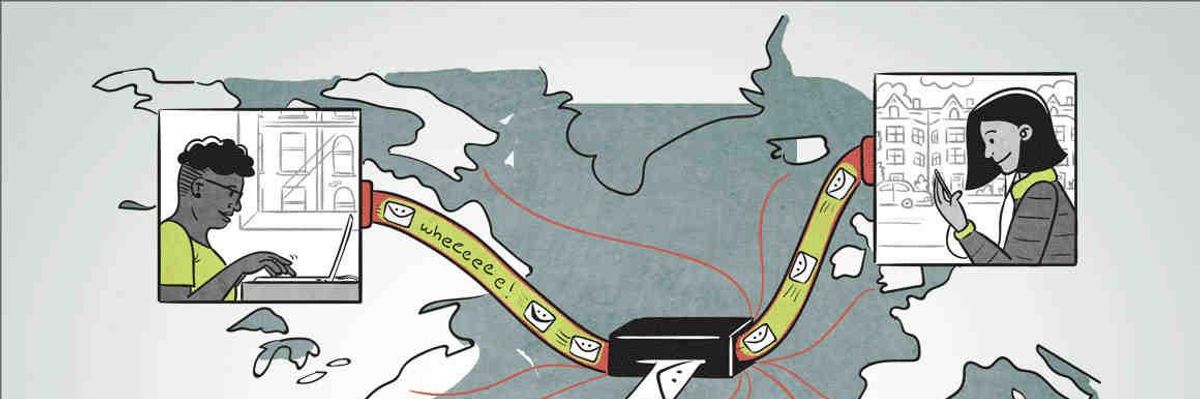

Upstream surveillance takes place in the internet "backbone" -- the network of high-capacity cables, switches, and routers that carries Americans' domestic and international internet communications. The NSA has installed surveillance equipment at dozens of points along the internet backbone, allowing the government to copy and then search the contents of vast quantities of internet traffic as it flows past.

The government claims that Upstream surveillance is authorized by Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act. That law allows the NSA to engage in warrantless surveillance of Americans when they are communicating with so-called "targets" abroad. But these targets can be virtually any foreigner overseas -- including people who are not accused of any wrongdoing whatsoever, like journalists, lawyers, and human rights researchers. No judge signs off on the government's individual targets. Instead, the NSA secretly vacuums up millions of communications under a single court order each year.

One of the most glaring problems with Upstream surveillance is that it is not targeted at all -- at least not in any ordinary sense of the word. Instead, the government is systematically examining online communications in bulk, scanning their full contents to see which ones merely mention its targets.

Because of how it operates, Upstream surveillance represents a new surveillance paradigm, one in which computers constantly scan our communications for information of interest to the government. To use a non-digital analogy: It's as if the NSA sent agents to the U.S. Postal Service's major processing centers to conduct continuous searches of everyone's international mail. The agents would open, copy, and read each letter, and would keep a copy of any letter that mentioned specific items of interest -- despite the fact that the government had no reason to suspect the letter's sender or recipient beforehand.

The ACLU brought this lawsuit on behalf of a coalition of legal, media, educational, and human rights organizations, including the Wikimedia Foundation (which runs Wikipedia), Amnesty International USA, The Nation magazine, PEN American Center, Human Rights Watch, the Rutherford Institute, the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, Global Fund for Women, and the Washington Office on Latin America.

Each of these nine plaintiffs has been deeply affected by U.S. government spying. The confidentiality of plaintiffs' international communications is essential to their work, and Upstream surveillance undermines their ability to ensure that these communications -- with colleagues, journalists, witnesses, foreign government officials, victims of human rights abuses, and the tens of millions of people who read and edit Wikipedia -- are indeed private. This spying violates our clients' constitutional rights to privacy, freedom of expression, and freedom of association.

Last year, a federal district court in Maryland dismissed our suit, wrongly concluding that our clients lack standing to challenge Upstream surveillance because they had not "plausibly" alleged that their communications are intercepted. Without standing, our plaintiffs can't have their day in court to challenge this spying on the merits.

However, as we explained in our appeal briefs, it's more than plausible that our clients' communications are intercepted: the government's own disclosures about Upstream surveillance, along with media reports, show that the NSA is vacuuming up and reviewing almost all text-based communications that enter and leave the country.

Wikimedia alone engages in over a trillion internet communications each year, with individuals located in virtually every country on earth. Given the volume and geographic distribution of these communications, it's indisputable that plaintiffs' communications are ensnared by the NSA.

We hope that the Fourth Circuit agrees. With President-elect Trump about to take over, there's simply too much at stake for the judiciary to close the courthouse doors on those harmed by mass surveillance.

Originally posted at The Daily Beast.