SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

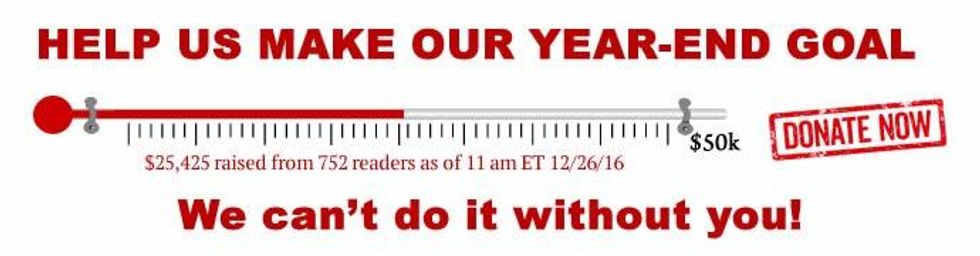

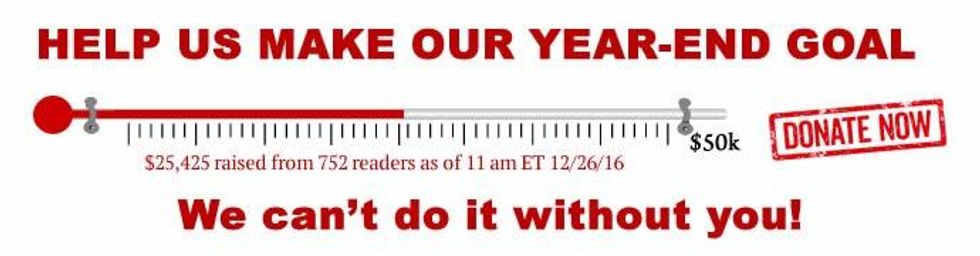

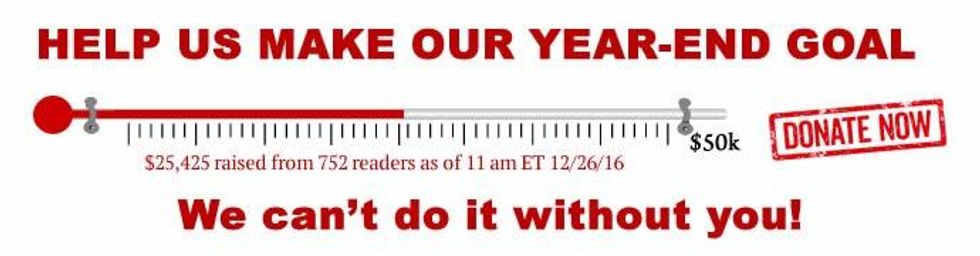

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

Chris Budicin, a student at Sierra Nevada College, paddles a canoe from Arctic Village into the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. (Photo: Brannan Lagasse)

I'd like to reframe what happened in early November as the opposite of tragedy. Instead of looking at the election results through a lens of doom and gloom, let us view this moment in history as a leverage point, one that has the ability to unite people across the country and the world.

If we are to capitalize on such a moment of opportunity, hope will be crucial. And although looking for it in the media can be like searching for a needle in a haystack, you can find real hope, active hope, where struggles transform into solutions.

Let us view this moment in history as a leverage point.

On Tuesday, President Obama joined Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau in protecting vibrant and vulnerable ocean ecosystems from future fossil fuel exploitation, and designated the vast majority of Arctic waters and millions of acres of the Atlantic as indefinitely off-limits to offshore oil and gas leasing.

Today, we can further engage in active hope by continuing this momentum and pressuring the administration to do as much good as possible before leaving office. To that end, permanently protecting the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, a pristine and fragile wilderness in Alaska's North Slope, would be a monumental and fully possible action that could push hope into lived reality.

Although Arctic Alaska is far removed from the day-to-day existence of most Americans, decisions made there reverberate across the country. The refuge encompasses more than 19 million acres, and is home to the Gwich'in Tribe, which shares the land with birds that migrate to and from all 50 U.S. states, polar and grizzly bears, and the Porcupine Caribou herd. The northernmost region, known as Area 1002, is where the caribou come to birth their calves each year. This combination of biological and cultural diversity is one of the most brilliant in the world.

If not for the wealth of oil, the area known by many as "the last great wilderness" might be left alone. Instead, it has been in conflict for decades. It is one of the few regions of the Alaskan Arctic that has not been developed for petroleum extraction.

The oil industry has tried to drill in the Arctic Refuge since its inception, but, fight after fight, environment and community have won. The reason? The relentless work of the Gwich'in people in a struggle to survive, supported by the leadership of elder Sarah James and the Gwich'in Steering Committee.

"We believe everything is connected. The land, the water, the caribou--all of it," James said. "We know that drilling for oil in the Arctic Refuge would hurt the land and the caribou. That's why we need to protect the refuge and the Coastal Plain."

In 1988, after hearing that the refuge might be opened for resource extraction, the Gwich'in gathered as a Nation for the first time in more than 100 years. Of the many empowering sentiments and actions shared during the gathering, they decided to take their story out of the Arctic, rallying old friends and making new ones to share in their struggle to protect this unique place.

This struggle is as much one for biodiversity as it is for Indigenous and human rights. As first people of the area, the Gwich'in have a history of oppression much like Indigenous people across the planet. They have a deep connection to the land, and especially the Porcupine Caribou. Gwich'in literally translates to "people of the caribou," and the tribe is inextricably linked to the health and well-being of the herd--economically for their sustenance, culturally for their identity, and spiritually for their worldview.

"The caribou gives us life. This is our way of life, to respect the land, the caribou, and our people," James said. If the caribou go, then the Gwich'in will go as well. And if Area 1002 is developed for oil extraction, the caribou will be displaced from their only birthing grounds.

There is a solution here, and it is to permanently protect the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

Knowing the incoming administration is backward on issues of climate and ecosystem health, and that the president-elect ran on a platform of increased domestic oil production, makes ensuring a just end in this case more important than ever. Beyond strong policy that binds nations to limiting and reducing their greenhouse gas emissions, supporting divestment and the movement to "keep it in the ground" is crucial. President Obama has made great gains in recent days and throughout his two terms by protecting more land and water than any president in history. His administration has even recommended that Congress designate the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge as wilderness, the country's strongest land protection designation.

But time to act is running out.

Oil companies are going farther and farther to extract every drop of accessible oil. This search to increase profit margins puts the environment at greater risk and perpetuates a system even Exxon knows is harming all life on Earth. Researchers estimate the amount of extractable oil in the refuge to be about six months-worth at the current rate of consumption. You read that right, six months. Less than 200 days of oil, and extracting it could cause irreparable damage to this pristine environment, perpetuate outdated and harmful thinking, and continue a legacy of marginalization of Indigenous people.

Wilderness designation has been a contentious issue for years and will not happen before the change of hands takes place in January. But President Obama can, in fact, take a step toward permanent protection by declaring the Arctic Refuge a National Monument under the Antiquities Act of 1906. This move would protect this unmatched environment, respect the community self-determination of the region's first peoples, and take a concrete step away from fossil fuels.

I have been lucky to to work with the Gwich'in Tribe in Arctic Village. My students and I have been welcomed to learn from locals like Sarah James about the importance of the refuge to the people, the caribou, and the rest of the world. There is a solution here, and it is to permanently protect the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

I'd like to reframe what happened in early November as the opposite of tragedy. Instead of looking at the election results through a lens of doom and gloom, let us view this moment in history as a leverage point, one that has the ability to unite people across the country and the world.

If we are to capitalize on such a moment of opportunity, hope will be crucial. And although looking for it in the media can be like searching for a needle in a haystack, you can find real hope, active hope, where struggles transform into solutions.

Let us view this moment in history as a leverage point.

On Tuesday, President Obama joined Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau in protecting vibrant and vulnerable ocean ecosystems from future fossil fuel exploitation, and designated the vast majority of Arctic waters and millions of acres of the Atlantic as indefinitely off-limits to offshore oil and gas leasing.

Today, we can further engage in active hope by continuing this momentum and pressuring the administration to do as much good as possible before leaving office. To that end, permanently protecting the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, a pristine and fragile wilderness in Alaska's North Slope, would be a monumental and fully possible action that could push hope into lived reality.

Although Arctic Alaska is far removed from the day-to-day existence of most Americans, decisions made there reverberate across the country. The refuge encompasses more than 19 million acres, and is home to the Gwich'in Tribe, which shares the land with birds that migrate to and from all 50 U.S. states, polar and grizzly bears, and the Porcupine Caribou herd. The northernmost region, known as Area 1002, is where the caribou come to birth their calves each year. This combination of biological and cultural diversity is one of the most brilliant in the world.

If not for the wealth of oil, the area known by many as "the last great wilderness" might be left alone. Instead, it has been in conflict for decades. It is one of the few regions of the Alaskan Arctic that has not been developed for petroleum extraction.

The oil industry has tried to drill in the Arctic Refuge since its inception, but, fight after fight, environment and community have won. The reason? The relentless work of the Gwich'in people in a struggle to survive, supported by the leadership of elder Sarah James and the Gwich'in Steering Committee.

"We believe everything is connected. The land, the water, the caribou--all of it," James said. "We know that drilling for oil in the Arctic Refuge would hurt the land and the caribou. That's why we need to protect the refuge and the Coastal Plain."

In 1988, after hearing that the refuge might be opened for resource extraction, the Gwich'in gathered as a Nation for the first time in more than 100 years. Of the many empowering sentiments and actions shared during the gathering, they decided to take their story out of the Arctic, rallying old friends and making new ones to share in their struggle to protect this unique place.

This struggle is as much one for biodiversity as it is for Indigenous and human rights. As first people of the area, the Gwich'in have a history of oppression much like Indigenous people across the planet. They have a deep connection to the land, and especially the Porcupine Caribou. Gwich'in literally translates to "people of the caribou," and the tribe is inextricably linked to the health and well-being of the herd--economically for their sustenance, culturally for their identity, and spiritually for their worldview.

"The caribou gives us life. This is our way of life, to respect the land, the caribou, and our people," James said. If the caribou go, then the Gwich'in will go as well. And if Area 1002 is developed for oil extraction, the caribou will be displaced from their only birthing grounds.

There is a solution here, and it is to permanently protect the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

Knowing the incoming administration is backward on issues of climate and ecosystem health, and that the president-elect ran on a platform of increased domestic oil production, makes ensuring a just end in this case more important than ever. Beyond strong policy that binds nations to limiting and reducing their greenhouse gas emissions, supporting divestment and the movement to "keep it in the ground" is crucial. President Obama has made great gains in recent days and throughout his two terms by protecting more land and water than any president in history. His administration has even recommended that Congress designate the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge as wilderness, the country's strongest land protection designation.

But time to act is running out.

Oil companies are going farther and farther to extract every drop of accessible oil. This search to increase profit margins puts the environment at greater risk and perpetuates a system even Exxon knows is harming all life on Earth. Researchers estimate the amount of extractable oil in the refuge to be about six months-worth at the current rate of consumption. You read that right, six months. Less than 200 days of oil, and extracting it could cause irreparable damage to this pristine environment, perpetuate outdated and harmful thinking, and continue a legacy of marginalization of Indigenous people.

Wilderness designation has been a contentious issue for years and will not happen before the change of hands takes place in January. But President Obama can, in fact, take a step toward permanent protection by declaring the Arctic Refuge a National Monument under the Antiquities Act of 1906. This move would protect this unmatched environment, respect the community self-determination of the region's first peoples, and take a concrete step away from fossil fuels.

I have been lucky to to work with the Gwich'in Tribe in Arctic Village. My students and I have been welcomed to learn from locals like Sarah James about the importance of the refuge to the people, the caribou, and the rest of the world. There is a solution here, and it is to permanently protect the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

I'd like to reframe what happened in early November as the opposite of tragedy. Instead of looking at the election results through a lens of doom and gloom, let us view this moment in history as a leverage point, one that has the ability to unite people across the country and the world.

If we are to capitalize on such a moment of opportunity, hope will be crucial. And although looking for it in the media can be like searching for a needle in a haystack, you can find real hope, active hope, where struggles transform into solutions.

Let us view this moment in history as a leverage point.

On Tuesday, President Obama joined Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau in protecting vibrant and vulnerable ocean ecosystems from future fossil fuel exploitation, and designated the vast majority of Arctic waters and millions of acres of the Atlantic as indefinitely off-limits to offshore oil and gas leasing.

Today, we can further engage in active hope by continuing this momentum and pressuring the administration to do as much good as possible before leaving office. To that end, permanently protecting the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, a pristine and fragile wilderness in Alaska's North Slope, would be a monumental and fully possible action that could push hope into lived reality.

Although Arctic Alaska is far removed from the day-to-day existence of most Americans, decisions made there reverberate across the country. The refuge encompasses more than 19 million acres, and is home to the Gwich'in Tribe, which shares the land with birds that migrate to and from all 50 U.S. states, polar and grizzly bears, and the Porcupine Caribou herd. The northernmost region, known as Area 1002, is where the caribou come to birth their calves each year. This combination of biological and cultural diversity is one of the most brilliant in the world.

If not for the wealth of oil, the area known by many as "the last great wilderness" might be left alone. Instead, it has been in conflict for decades. It is one of the few regions of the Alaskan Arctic that has not been developed for petroleum extraction.

The oil industry has tried to drill in the Arctic Refuge since its inception, but, fight after fight, environment and community have won. The reason? The relentless work of the Gwich'in people in a struggle to survive, supported by the leadership of elder Sarah James and the Gwich'in Steering Committee.

"We believe everything is connected. The land, the water, the caribou--all of it," James said. "We know that drilling for oil in the Arctic Refuge would hurt the land and the caribou. That's why we need to protect the refuge and the Coastal Plain."

In 1988, after hearing that the refuge might be opened for resource extraction, the Gwich'in gathered as a Nation for the first time in more than 100 years. Of the many empowering sentiments and actions shared during the gathering, they decided to take their story out of the Arctic, rallying old friends and making new ones to share in their struggle to protect this unique place.

This struggle is as much one for biodiversity as it is for Indigenous and human rights. As first people of the area, the Gwich'in have a history of oppression much like Indigenous people across the planet. They have a deep connection to the land, and especially the Porcupine Caribou. Gwich'in literally translates to "people of the caribou," and the tribe is inextricably linked to the health and well-being of the herd--economically for their sustenance, culturally for their identity, and spiritually for their worldview.

"The caribou gives us life. This is our way of life, to respect the land, the caribou, and our people," James said. If the caribou go, then the Gwich'in will go as well. And if Area 1002 is developed for oil extraction, the caribou will be displaced from their only birthing grounds.

There is a solution here, and it is to permanently protect the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

Knowing the incoming administration is backward on issues of climate and ecosystem health, and that the president-elect ran on a platform of increased domestic oil production, makes ensuring a just end in this case more important than ever. Beyond strong policy that binds nations to limiting and reducing their greenhouse gas emissions, supporting divestment and the movement to "keep it in the ground" is crucial. President Obama has made great gains in recent days and throughout his two terms by protecting more land and water than any president in history. His administration has even recommended that Congress designate the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge as wilderness, the country's strongest land protection designation.

But time to act is running out.

Oil companies are going farther and farther to extract every drop of accessible oil. This search to increase profit margins puts the environment at greater risk and perpetuates a system even Exxon knows is harming all life on Earth. Researchers estimate the amount of extractable oil in the refuge to be about six months-worth at the current rate of consumption. You read that right, six months. Less than 200 days of oil, and extracting it could cause irreparable damage to this pristine environment, perpetuate outdated and harmful thinking, and continue a legacy of marginalization of Indigenous people.

Wilderness designation has been a contentious issue for years and will not happen before the change of hands takes place in January. But President Obama can, in fact, take a step toward permanent protection by declaring the Arctic Refuge a National Monument under the Antiquities Act of 1906. This move would protect this unmatched environment, respect the community self-determination of the region's first peoples, and take a concrete step away from fossil fuels.

I have been lucky to to work with the Gwich'in Tribe in Arctic Village. My students and I have been welcomed to learn from locals like Sarah James about the importance of the refuge to the people, the caribou, and the rest of the world. There is a solution here, and it is to permanently protect the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.