SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

(Image: Oxfam International)

It's Davos this week, which means it's time for Oxfam's latest global 'killer fact' on extreme inequality. Since our first calculation in 2014, these have helped get inequality onto the agenda of the global leaders assembled in Switzerland. This year, the grabber of any headlines not devoted to the US presidential inauguration on Friday is that it's worse than we thought. Last year it was 62 people who owned the same as the poorest half of the world. This year it is down to 8. Just 8 men. Have as much wealth as 3.6 billion poor men, women and children. Think about that for a moment, before getting geeky and carrying on with the rest of this post.

Every year, there are also regular attempts at rubbishing the new stat. An admirably nerdy box in Oxfam's new paper for Davos both explains the origins of the new number (better data) and addresses the expected counterarguments.

'In January 2014, Oxfam calculated that just 85 people had the same amount of wealth as the bottom half of humanity. This was based on data on the net wealth of the richest individuals from Forbes and data on the global wealth distribution from Credit Suisse. For the past three years, we have been tracking these data sources to understand how the global wealth distribution is evolving. In the Credit Suisse report of October 2015, the richest 1% had the same amount of wealth as the other 99%.

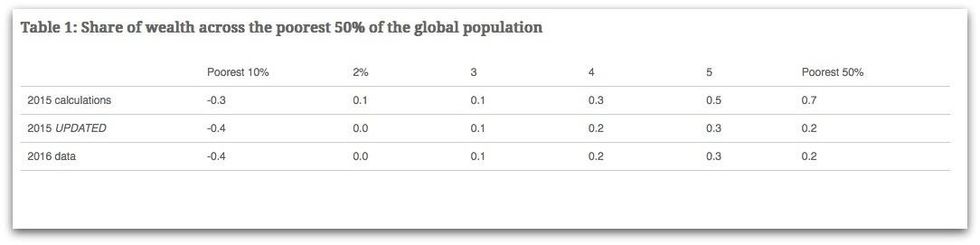

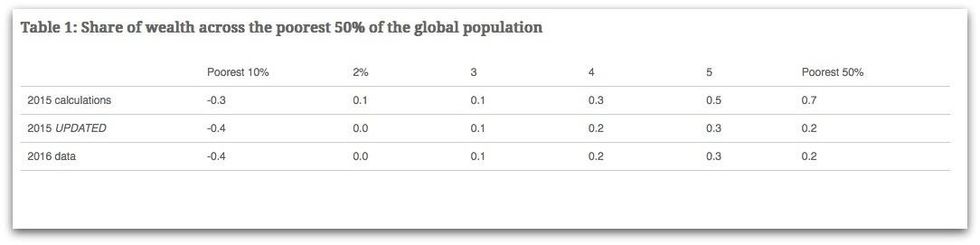

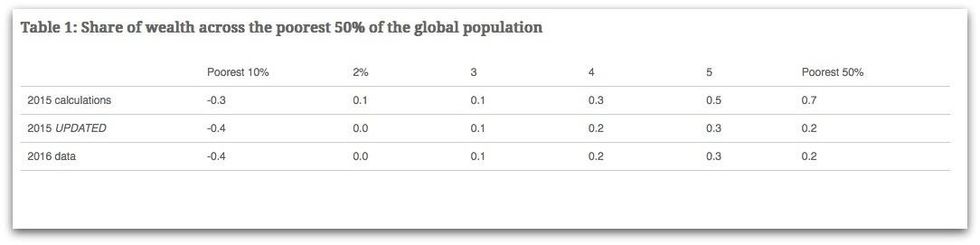

This year we find that the wealth of the bottom 50% of the global population was lower than previously estimated, and it takes just eight individuals to equal their total wealth holdings. Every year, Credit Suisse acquires new and better data sources with which to estimate the global wealth distribution: its latest report shows both that there is more debt in the very poorest group and fewer assets in the 30-50% percentiles of the global population. Last year it was estimated that the cumulative share of wealth of the poorest 50% was 0.7%; this year it is 0.2%.

The inequality of wealth that these calculations illustrate has attracted a lot of attention, both to the obscene level of inequality they expose and to the underlying data and the calculations themselves. Two common challenges are heard. First, that the poorest people are in net debt, but these people may be income-rich thanks to well-functioning credit markets (think of the indebted Harvard graduate). However, in terms of population, this group is insignificant at the aggregate global level, where 70% of people in the bottom 50% live in low-income countries. The total net debt of the bottom 50% of the global population is also just 0.4% of overall global wealth, or $1.1 trillion. If you ignore the net debt, the wealth of the bottom 50% is $1.5 trillion. It still takes just 56 of the wealthiest individuals to equal the wealth of this group.

The second challenge is that changes over time of net wealth can be due to exchange-rate fluctuations, which matter little to people who want to use their wealth domestically. As the Credit Suisse reports in US$, it is of course true that wealth held in other currencies must be converted to US$. Indeed, wealth in the UK declined by $1.5 trillion over the past year due to the decline in the value of Sterling. However, exchange-rate fluctuations cannot explain the long-run persistent wealth inequality which Credit Suisse shows (using current exchange rates): the bottom 50% have never had more than 1.5% of total wealth since 2000, and the richest 1% have never had less than 46%. Given the importance of globally traded capital in total wealth stocks, exchange rates remain an appropriate way to convert between currencies.'

The paper has a larger aim, setting out some initial thinking on the constituent elements of a 'human economy approach' that can turn around both inequality and other public bads created by prevailing orthodoxies. Here are the headlines:

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

It's Davos this week, which means it's time for Oxfam's latest global 'killer fact' on extreme inequality. Since our first calculation in 2014, these have helped get inequality onto the agenda of the global leaders assembled in Switzerland. This year, the grabber of any headlines not devoted to the US presidential inauguration on Friday is that it's worse than we thought. Last year it was 62 people who owned the same as the poorest half of the world. This year it is down to 8. Just 8 men. Have as much wealth as 3.6 billion poor men, women and children. Think about that for a moment, before getting geeky and carrying on with the rest of this post.

Every year, there are also regular attempts at rubbishing the new stat. An admirably nerdy box in Oxfam's new paper for Davos both explains the origins of the new number (better data) and addresses the expected counterarguments.

'In January 2014, Oxfam calculated that just 85 people had the same amount of wealth as the bottom half of humanity. This was based on data on the net wealth of the richest individuals from Forbes and data on the global wealth distribution from Credit Suisse. For the past three years, we have been tracking these data sources to understand how the global wealth distribution is evolving. In the Credit Suisse report of October 2015, the richest 1% had the same amount of wealth as the other 99%.

This year we find that the wealth of the bottom 50% of the global population was lower than previously estimated, and it takes just eight individuals to equal their total wealth holdings. Every year, Credit Suisse acquires new and better data sources with which to estimate the global wealth distribution: its latest report shows both that there is more debt in the very poorest group and fewer assets in the 30-50% percentiles of the global population. Last year it was estimated that the cumulative share of wealth of the poorest 50% was 0.7%; this year it is 0.2%.

The inequality of wealth that these calculations illustrate has attracted a lot of attention, both to the obscene level of inequality they expose and to the underlying data and the calculations themselves. Two common challenges are heard. First, that the poorest people are in net debt, but these people may be income-rich thanks to well-functioning credit markets (think of the indebted Harvard graduate). However, in terms of population, this group is insignificant at the aggregate global level, where 70% of people in the bottom 50% live in low-income countries. The total net debt of the bottom 50% of the global population is also just 0.4% of overall global wealth, or $1.1 trillion. If you ignore the net debt, the wealth of the bottom 50% is $1.5 trillion. It still takes just 56 of the wealthiest individuals to equal the wealth of this group.

The second challenge is that changes over time of net wealth can be due to exchange-rate fluctuations, which matter little to people who want to use their wealth domestically. As the Credit Suisse reports in US$, it is of course true that wealth held in other currencies must be converted to US$. Indeed, wealth in the UK declined by $1.5 trillion over the past year due to the decline in the value of Sterling. However, exchange-rate fluctuations cannot explain the long-run persistent wealth inequality which Credit Suisse shows (using current exchange rates): the bottom 50% have never had more than 1.5% of total wealth since 2000, and the richest 1% have never had less than 46%. Given the importance of globally traded capital in total wealth stocks, exchange rates remain an appropriate way to convert between currencies.'

The paper has a larger aim, setting out some initial thinking on the constituent elements of a 'human economy approach' that can turn around both inequality and other public bads created by prevailing orthodoxies. Here are the headlines:

It's Davos this week, which means it's time for Oxfam's latest global 'killer fact' on extreme inequality. Since our first calculation in 2014, these have helped get inequality onto the agenda of the global leaders assembled in Switzerland. This year, the grabber of any headlines not devoted to the US presidential inauguration on Friday is that it's worse than we thought. Last year it was 62 people who owned the same as the poorest half of the world. This year it is down to 8. Just 8 men. Have as much wealth as 3.6 billion poor men, women and children. Think about that for a moment, before getting geeky and carrying on with the rest of this post.

Every year, there are also regular attempts at rubbishing the new stat. An admirably nerdy box in Oxfam's new paper for Davos both explains the origins of the new number (better data) and addresses the expected counterarguments.

'In January 2014, Oxfam calculated that just 85 people had the same amount of wealth as the bottom half of humanity. This was based on data on the net wealth of the richest individuals from Forbes and data on the global wealth distribution from Credit Suisse. For the past three years, we have been tracking these data sources to understand how the global wealth distribution is evolving. In the Credit Suisse report of October 2015, the richest 1% had the same amount of wealth as the other 99%.

This year we find that the wealth of the bottom 50% of the global population was lower than previously estimated, and it takes just eight individuals to equal their total wealth holdings. Every year, Credit Suisse acquires new and better data sources with which to estimate the global wealth distribution: its latest report shows both that there is more debt in the very poorest group and fewer assets in the 30-50% percentiles of the global population. Last year it was estimated that the cumulative share of wealth of the poorest 50% was 0.7%; this year it is 0.2%.

The inequality of wealth that these calculations illustrate has attracted a lot of attention, both to the obscene level of inequality they expose and to the underlying data and the calculations themselves. Two common challenges are heard. First, that the poorest people are in net debt, but these people may be income-rich thanks to well-functioning credit markets (think of the indebted Harvard graduate). However, in terms of population, this group is insignificant at the aggregate global level, where 70% of people in the bottom 50% live in low-income countries. The total net debt of the bottom 50% of the global population is also just 0.4% of overall global wealth, or $1.1 trillion. If you ignore the net debt, the wealth of the bottom 50% is $1.5 trillion. It still takes just 56 of the wealthiest individuals to equal the wealth of this group.

The second challenge is that changes over time of net wealth can be due to exchange-rate fluctuations, which matter little to people who want to use their wealth domestically. As the Credit Suisse reports in US$, it is of course true that wealth held in other currencies must be converted to US$. Indeed, wealth in the UK declined by $1.5 trillion over the past year due to the decline in the value of Sterling. However, exchange-rate fluctuations cannot explain the long-run persistent wealth inequality which Credit Suisse shows (using current exchange rates): the bottom 50% have never had more than 1.5% of total wealth since 2000, and the richest 1% have never had less than 46%. Given the importance of globally traded capital in total wealth stocks, exchange rates remain an appropriate way to convert between currencies.'

The paper has a larger aim, setting out some initial thinking on the constituent elements of a 'human economy approach' that can turn around both inequality and other public bads created by prevailing orthodoxies. Here are the headlines: