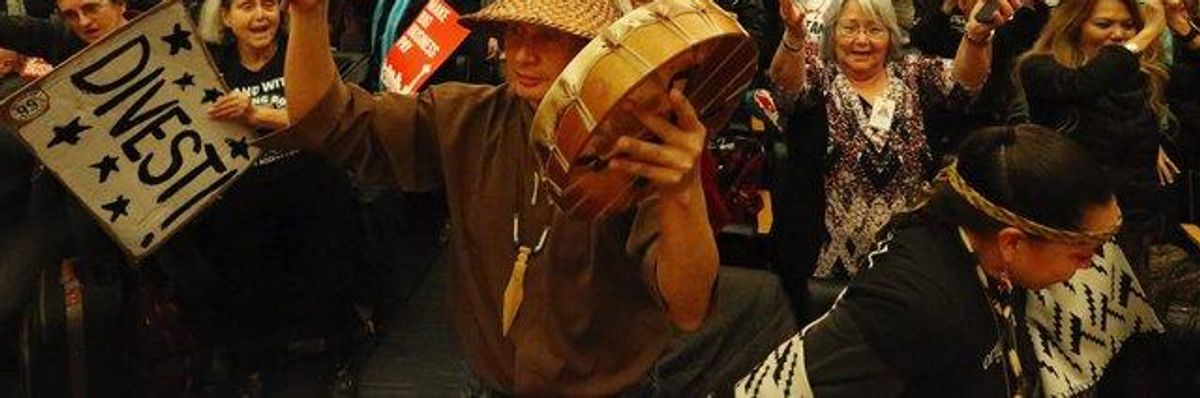

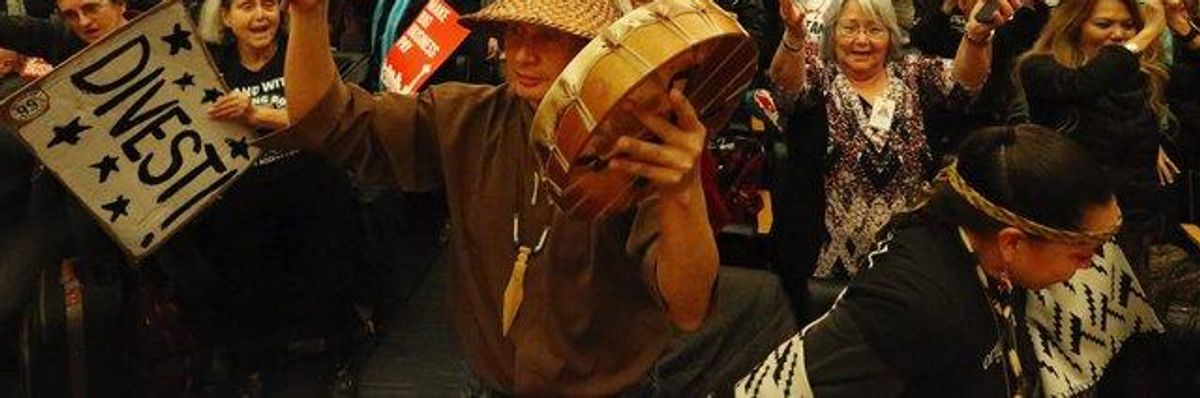

A packed Seattle City Council chamber cheers passage of the bill to drop Wells Fargo as its bank. (Photo: Ken Lambert / The Seattle Times)

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

A packed Seattle City Council chamber cheers passage of the bill to drop Wells Fargo as its bank. (Photo: Ken Lambert / The Seattle Times)

The movement to stop the controversial Dakota Access pipeline through financial activism took an important step forward today, as the Seattle City Council voted 9-0 to approve a bill that terminates a valuable city contract with Wells Fargo. The bank, one of the largest in the United States, has provided more than $450 million in credit to the companies building the pipeline.

The move makes Seattle the first city to divest from a financial institution because of its role in the Dakota Access pipeline, a $3.8 billion project that would run from western North Dakota to Illinois, and is fiercely opposed by the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. Wells Fargo is one of 17 banks directly financing the project.

For Olivia One Feather, a Lakota Sioux tribal member who drove more than 1,200 miles from North Dakota to testify in favor of divestment, the day was bittersweet. She was excited about the ordinance, she said, but horrified by news that the Army Corps of Engineers was about to grant an easement to move the pipeline project forward.

The current divestment campaign began at the individual level, as people withdrew funds or closed accounts--a tactic that has taken more than $57 million out of DAPL-financing banks so far, according to the website DefundDAPL. But as divestment spreads to municipalities, tribes, and universities, the amount of money at stake becomes much larger. About $3 billion moves in and out of Seattle's accounts with Wells Fargo each year, according to the Seattle Weekly.

"People might argue that Seattle's $3 billion account is just a blip on the radar for Wells Fargo, but this movement is poised to scale up," said Hugh MacMillan, a senior researcher at the environmental nonprofit Food & Water Watch. "I think you'll see more cities following Seattle's lead."

Matt Remle, a Seattle-based organizer who is a member of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, agrees. He says he's been in talks with community leaders in a number of other cities, and they're looking to divest from Wells Fargo too.

"I think you'll see more cities following Seattle's lead."

Minneapolis is perhaps the furthest along. Last December, the city council there asked its staff to research ways to stop doing business with financial institutions that help finance the Dakota Access pipeline and other fossil fuel projects. Alondra Cano, one of the city councilmembers who made that proposal, says it's already producing results. "We're now exploring new banking structures that will put us more in line with our interests in doing business with organizations and banking institutions that aren't damaging the environment," she said.

Cano points out that the city's current contract with Wells Fargo doesn't end until 2018, so the city has time to plan its next moves. And Seattle's new ordinance will help, she said. "Any time other municipalities of similar size and character are able to move forward down the path of divestment, it makes it easier for sister municipalities like ours to do the same thing," she explained. "I'm excited to see their results and possibly exchange ideas and strategies about divestment, about making that a reality for our cities."

Elected officials in at least three other cities--including Boulder, Colorado; Santa Fe, New Mexico; and Portland, Oregon--have indicated that they might soon decide to follow a similar path. Boulder's city council voted on Jan. 31 to investigate alternatives to banking with JPMorgan Chase, another financial supporter of the Dakota Access pipeline.

"People might argue that Seattle's $3 billion account is just a blip on the radar for Wells Fargo, but this movement is poised to scale up."

Divesting from one bank means finding another one, and Seattle's ordinance also lays out a new way of doing that. The bill orders the city to create a "competitive bidding process" to find a new banking partner by Dec. 18, 2018, which is when the current contract with Wells Fargo ends. The city will consider "socially responsible banking and fair business practices" as a factor in its decision.

Kshama Sawant, the socialist Seattle council member who co-sponsored the bill, has advocated that Seattle choose a credit union or create a public, city-owned bank. However, a Washington State law effectively prohibits cities from banking with credit unions.

In the meantime, allies continue to express support. Last Friday, the prominent writer and Black Lives Matter activist Shaun King hailed Seattle's move as "a huge deal." He went on to address the banks directly: "If you fund our oppression, if you fund injustice, or if you are willfully silent in the face of those things, people are organizing to defund you and find banks, businesses, and financial institutions that will openly agree to humane values and principles."

Eleanor Stevens provided additional reporting for this article.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

The movement to stop the controversial Dakota Access pipeline through financial activism took an important step forward today, as the Seattle City Council voted 9-0 to approve a bill that terminates a valuable city contract with Wells Fargo. The bank, one of the largest in the United States, has provided more than $450 million in credit to the companies building the pipeline.

The move makes Seattle the first city to divest from a financial institution because of its role in the Dakota Access pipeline, a $3.8 billion project that would run from western North Dakota to Illinois, and is fiercely opposed by the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. Wells Fargo is one of 17 banks directly financing the project.

For Olivia One Feather, a Lakota Sioux tribal member who drove more than 1,200 miles from North Dakota to testify in favor of divestment, the day was bittersweet. She was excited about the ordinance, she said, but horrified by news that the Army Corps of Engineers was about to grant an easement to move the pipeline project forward.

The current divestment campaign began at the individual level, as people withdrew funds or closed accounts--a tactic that has taken more than $57 million out of DAPL-financing banks so far, according to the website DefundDAPL. But as divestment spreads to municipalities, tribes, and universities, the amount of money at stake becomes much larger. About $3 billion moves in and out of Seattle's accounts with Wells Fargo each year, according to the Seattle Weekly.

"People might argue that Seattle's $3 billion account is just a blip on the radar for Wells Fargo, but this movement is poised to scale up," said Hugh MacMillan, a senior researcher at the environmental nonprofit Food & Water Watch. "I think you'll see more cities following Seattle's lead."

Matt Remle, a Seattle-based organizer who is a member of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, agrees. He says he's been in talks with community leaders in a number of other cities, and they're looking to divest from Wells Fargo too.

"I think you'll see more cities following Seattle's lead."

Minneapolis is perhaps the furthest along. Last December, the city council there asked its staff to research ways to stop doing business with financial institutions that help finance the Dakota Access pipeline and other fossil fuel projects. Alondra Cano, one of the city councilmembers who made that proposal, says it's already producing results. "We're now exploring new banking structures that will put us more in line with our interests in doing business with organizations and banking institutions that aren't damaging the environment," she said.

Cano points out that the city's current contract with Wells Fargo doesn't end until 2018, so the city has time to plan its next moves. And Seattle's new ordinance will help, she said. "Any time other municipalities of similar size and character are able to move forward down the path of divestment, it makes it easier for sister municipalities like ours to do the same thing," she explained. "I'm excited to see their results and possibly exchange ideas and strategies about divestment, about making that a reality for our cities."

Elected officials in at least three other cities--including Boulder, Colorado; Santa Fe, New Mexico; and Portland, Oregon--have indicated that they might soon decide to follow a similar path. Boulder's city council voted on Jan. 31 to investigate alternatives to banking with JPMorgan Chase, another financial supporter of the Dakota Access pipeline.

"People might argue that Seattle's $3 billion account is just a blip on the radar for Wells Fargo, but this movement is poised to scale up."

Divesting from one bank means finding another one, and Seattle's ordinance also lays out a new way of doing that. The bill orders the city to create a "competitive bidding process" to find a new banking partner by Dec. 18, 2018, which is when the current contract with Wells Fargo ends. The city will consider "socially responsible banking and fair business practices" as a factor in its decision.

Kshama Sawant, the socialist Seattle council member who co-sponsored the bill, has advocated that Seattle choose a credit union or create a public, city-owned bank. However, a Washington State law effectively prohibits cities from banking with credit unions.

In the meantime, allies continue to express support. Last Friday, the prominent writer and Black Lives Matter activist Shaun King hailed Seattle's move as "a huge deal." He went on to address the banks directly: "If you fund our oppression, if you fund injustice, or if you are willfully silent in the face of those things, people are organizing to defund you and find banks, businesses, and financial institutions that will openly agree to humane values and principles."

Eleanor Stevens provided additional reporting for this article.

The movement to stop the controversial Dakota Access pipeline through financial activism took an important step forward today, as the Seattle City Council voted 9-0 to approve a bill that terminates a valuable city contract with Wells Fargo. The bank, one of the largest in the United States, has provided more than $450 million in credit to the companies building the pipeline.

The move makes Seattle the first city to divest from a financial institution because of its role in the Dakota Access pipeline, a $3.8 billion project that would run from western North Dakota to Illinois, and is fiercely opposed by the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. Wells Fargo is one of 17 banks directly financing the project.

For Olivia One Feather, a Lakota Sioux tribal member who drove more than 1,200 miles from North Dakota to testify in favor of divestment, the day was bittersweet. She was excited about the ordinance, she said, but horrified by news that the Army Corps of Engineers was about to grant an easement to move the pipeline project forward.

The current divestment campaign began at the individual level, as people withdrew funds or closed accounts--a tactic that has taken more than $57 million out of DAPL-financing banks so far, according to the website DefundDAPL. But as divestment spreads to municipalities, tribes, and universities, the amount of money at stake becomes much larger. About $3 billion moves in and out of Seattle's accounts with Wells Fargo each year, according to the Seattle Weekly.

"People might argue that Seattle's $3 billion account is just a blip on the radar for Wells Fargo, but this movement is poised to scale up," said Hugh MacMillan, a senior researcher at the environmental nonprofit Food & Water Watch. "I think you'll see more cities following Seattle's lead."

Matt Remle, a Seattle-based organizer who is a member of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, agrees. He says he's been in talks with community leaders in a number of other cities, and they're looking to divest from Wells Fargo too.

"I think you'll see more cities following Seattle's lead."

Minneapolis is perhaps the furthest along. Last December, the city council there asked its staff to research ways to stop doing business with financial institutions that help finance the Dakota Access pipeline and other fossil fuel projects. Alondra Cano, one of the city councilmembers who made that proposal, says it's already producing results. "We're now exploring new banking structures that will put us more in line with our interests in doing business with organizations and banking institutions that aren't damaging the environment," she said.

Cano points out that the city's current contract with Wells Fargo doesn't end until 2018, so the city has time to plan its next moves. And Seattle's new ordinance will help, she said. "Any time other municipalities of similar size and character are able to move forward down the path of divestment, it makes it easier for sister municipalities like ours to do the same thing," she explained. "I'm excited to see their results and possibly exchange ideas and strategies about divestment, about making that a reality for our cities."

Elected officials in at least three other cities--including Boulder, Colorado; Santa Fe, New Mexico; and Portland, Oregon--have indicated that they might soon decide to follow a similar path. Boulder's city council voted on Jan. 31 to investigate alternatives to banking with JPMorgan Chase, another financial supporter of the Dakota Access pipeline.

"People might argue that Seattle's $3 billion account is just a blip on the radar for Wells Fargo, but this movement is poised to scale up."

Divesting from one bank means finding another one, and Seattle's ordinance also lays out a new way of doing that. The bill orders the city to create a "competitive bidding process" to find a new banking partner by Dec. 18, 2018, which is when the current contract with Wells Fargo ends. The city will consider "socially responsible banking and fair business practices" as a factor in its decision.

Kshama Sawant, the socialist Seattle council member who co-sponsored the bill, has advocated that Seattle choose a credit union or create a public, city-owned bank. However, a Washington State law effectively prohibits cities from banking with credit unions.

In the meantime, allies continue to express support. Last Friday, the prominent writer and Black Lives Matter activist Shaun King hailed Seattle's move as "a huge deal." He went on to address the banks directly: "If you fund our oppression, if you fund injustice, or if you are willfully silent in the face of those things, people are organizing to defund you and find banks, businesses, and financial institutions that will openly agree to humane values and principles."

Eleanor Stevens provided additional reporting for this article.