Time was, you didn't need a strike to create "A Day Without a Woman." That's just how things were. If you walked into any voting booth on Election Day, or watched any Supreme Court hearing, or tuned in at dinnertime to any television newscast, or found yourself on a rocket ship headed for the Moon, that's what you'd see: no women, nowhere. Not in the United States, not in most of the world.

Make it clear what it's like when women exclude themselves.

That much has changed, thanks in part to women's strikes, like the one being organized around the globe for Wednesday. The premise is simple: Stay home from work - paid or unpaid - and demonstrate your value by your absence. Make your voice heard by distancing it from the microphone. Whatever you normally do, don't.

Make it clear what it's like when women exclude themselves.

As the ancient Greeks saw it, abstinence makes the heart grow fonder.

The prototype was "Lysistrata," Aristophanes' bawdy tale of fifth-century BC Athenian women who denied sex to their men to put an end to the Peloponnesian War. Played more for laughs than liberation, it nonetheless paved the way for centuries of similar tactics, some of which - depending on what talents women withheld - actually worked.

A few millennia later in America, the currency was cooking or charity work, both of which were executed almost exclusively by women. On a summer speaking trip through Kansas in 1895, suffrage leader Susan B. Anthony was asked what women should do to speed up the process of getting the right to vote. "They ought to withdraw from all their charitable work and let the men run things for a while," she said merrily in Topeka. "[T]he women of Kansas should sit by and fold their hands. If they would stop their helping the men for six months, we would have equal suffrage granted us." The concept so amused Anthony, she later joked about "the men's howling over the idea that the women might possibly take our advice and sit down with folded hands refusing to do another thing to help them until the right of self government was accorded." She teased a reporter in Chicago about men's fears that "all women should cease even to cook dinner."

Our power is scary when you realize what it can accomplish. Over the years, women would also strike for peace, for improved working conditions, for whatever they were denied.

It would take another 25 years, but women's constant agitation won the right to vote in 1920. Our power is scary when you realize what it can accomplish. Over the years, women would also strike for peace, for improved working conditions, for whatever they were denied. Sometimes they struck out. Sometimes they struck a blow for history. The victories started to accrue.

By the late 1960s, despite half a century of suffrage and the doubling of women in the workforce over two decades, women were still undervalued, underpaid and underrepresented in leading professions. Never mind looking for a woman switching telephone lines, flying a commercial airliner, or rising to the level of U.S. Army general.

At the same time, poverty remained high in female-headed families. Politics was still mostly a boys' club. There were no female governors or big city mayors, no women in the US cabinet, only 10 in the House of Representatives and one in the Senate. As for the Oval Office, it remained an impossible dream in a nation where managers tended to look at a potential staffer's body before her resume.

The second wave of feminism revived the art form of the strike in the face of surprisingly glum statistics.

I'm talking about 1970 and the Women's Strike for Equality.

"Don't Iron While the Strike is Hot!" commanded strike organizer Betty Friedan, echoing Anthony's earlier marching orders to the nation's homemakers. "Sisterhood is Powerful!"

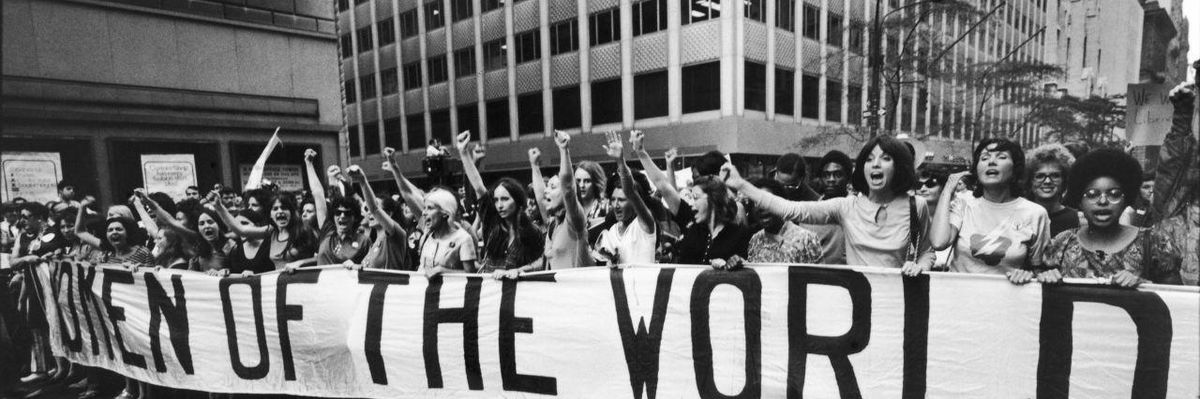

And how. On August 26, 50 years to the day after the 19th (the Suffrage) Amendment had passed, tens of thousands of American women abandoned their husbands, their desks, their typewriters and their waitress stations to march down the avenues in a number of cities to press for a new set of issues.

As a young reporter for the Associated Press (there were pockets of sanity in American society), I chronicled the journey of a self-described housewife and mom, 28, who lived in a conservative Republican section of Queens, New York. When the alarm sounded that morning, she bucked tradition and decided not to nudge her husband awake. "I thought, to heck with it. I'm on strike," she told me. Four hours later, she was cheering at a demonstration for childcare centers. And then, trailed by my notebook and me, she marched down Fifth Avenue clutching one-fifth of a banner urging the Senate to pass the Equal Rights Amendment.

The women's movement had gone mainstream.

The strike itself was described, at a time when police estimates actually mattered, as the largest demonstration ever held for women's rights. It led to the enormous advances so many of us enjoy today. So many, that for a time many of us believed the Revolution we'd just begun was actually over.

The 2016 election proved just how wrong we were.

The coarse misogyny of the campaign and the victorious candidate, along with new threats to women's health and bodies and rights and sanity, inspired the January 21 Women's March, an exhilarating day of purpose and uncommon wit. My thirteen-year-old granddaughter is still wearing the pink pussy hat she helped knit. A friend from Vermont giggled over a photo she took of two women carrying brass instruments and the hand-lettered sign, "Fallopian Tubas."

And when someone asked - pre-empting my own concern - what had really been accomplished, or was it just a feel-good event, someone else pointed out the rise of political activism, the rush to run for office, the numerous lists of Things You Can Do Every Day being emailed around cyberspace. As a result, the power and scope of the January 21 march has galvanized women for the next show of strength - today's women's strike.

Organizers understand that many women simply cannot stay off the job; that many more don't want to leave desperate clients without resources. No problem: Wear red as a show of solidarity; do something - anything - to support the cause. Just maintain the momentum.

"Life hands all of us setbacks," Hillary Clinton told a thousand cheering supporters at a New York luncheon Tuesday, accepting an award from Girls Inc. for her lifetime of inspiring girls and women. "Everyone gets knocked down. What matters is that you get up and keep going."

Shaun Robinson, the former TV anchor, now full-time social advocate, was more explicit. Advising a prizewinning Girls Inc. overachiever now headed for college, she said, "You fall down seven times, sister, you get up eight!"

Or, as the woman from Vermont put it, "Why am I taking part in the strike? It's simple: I'll keep going because I have to."

We all do. Because no day should ever be without a woman - unless it's our choice.