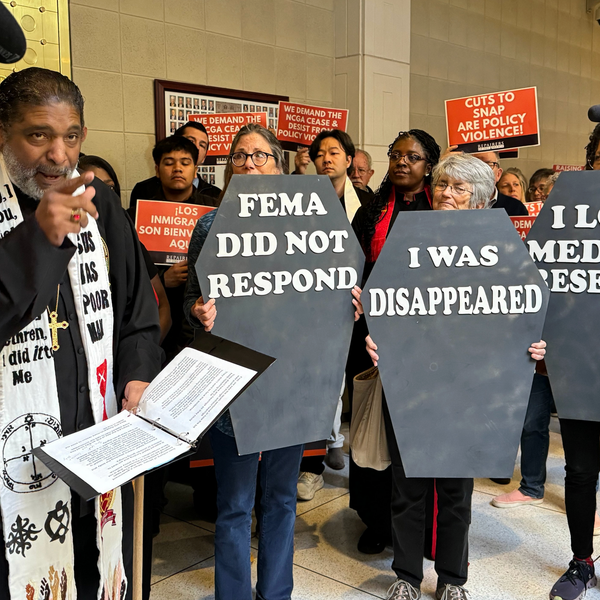

Once Congress both changes Medicaid's basic structure and enacts large annual savings, those cuts are highly unlikely to be reversed. (Photo: LaDawna Howard/flickr/cc)

Despite promises that the emerging Senate health bill will moderate the health coverage cuts in the House-passed American Health Care Act (AHCA), the Senate not only is retaining the House bill's fundamental restructuring of the Medicaid program -- a "per capita cap" on federal funding -- but is deepening the cuts under the per capita cap beginning around 2025.[1] Because the per capita cap wouldn't take effect until 2020 and the Senate's further cuts wouldn't kick in until five years after that, some suggest that policymakers might later undo the per capita cap itself or indefinitely delay the deeper cuts under pressure from state leaders, the public, providers, and others. This confidence is unwarranted; it ignores both recent history and the legislative constraints that would make it difficult or impossible to undo the deep Medicaid cuts.

Those structural changes would create a political dynamic that could lead to even larger cuts in the future. Once Congress both changes Medicaid's basic structure and enacts large annual savings, those cuts are highly unlikely to be reversed. In fact, those structural changes would create a political dynamic that could lead to even larger cuts in the future:

- History suggests that structural changes to Medicaid would be very difficult to reverse. The basic concept behind the per capita cap is to impose a cap on federal funding per beneficiary, replacing the existing commitment of the federal government to pay a fixed share of state Medicaid costs. Experience with other programs suggests that such radical structural changes won't be reversed. The conversion of the Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) entitlement program to the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) block grant in 1996 is instructive: TANF's block grant structure has not only persisted but also led to a continuing erosion of the program's funding and effectiveness.[2]

Indeed, the history of block grants (the closest analogy to a per capita cap) is that this structure enables deep cuts over time. Since 2000, funding for the 13 major housing, health, and social services block grants has fallen by 27 percent, after adjusting for inflation (and 37 percent after adjusting for inflation and population growth).[3]

- Experience shows that spending cuts are also difficult to undo - due to both legislative and political constraints. Commentators have analogized the future increase in the Medicaid cuts to expiring tax provisions or cuts to Medicare payments to physicians under the "sustainable growth rate" (SGR) formula -- measures that threatened sudden and painful cuts or tax increases, which Congress repeatedly delayed and ultimately largely reversed due to their political unpopularity. But recent history suggests that planned spending cuts aren't easy to undo. Unlike expiring tax provisions, both congressional rules and Republican demands may require "pay-fors" to offset the cost of reversing planned spending cuts. To reverse the spending cuts without offsetting the cost would likely require support from congressional leadership in both houses, 60 votes in the Senate, and support from the President.

Indeed, while canceling the planned SGR cuts was highly popular and supported by a vocal and powerful interest group, for nearly 20 years -- almost without exception -- Congress either offset the cuts with other cuts (frequently other health cuts) or let them take effect. The automatic "sequestration" cuts passed in 2011 to force further deficit reduction are another example: a significant share of the cuts have taken effect, and sequestration relief has required substantial offsets.

Reversing Medicaid cuts would require both a political consensus that they shouldn't have been enacted and sufficient congressional support to either waive budget rules or find painful offsets to achieve them. To be sure, Medicaid has broad-based support and affects a wide range of seniors, people with disabilities, and families with children. But reversing these cuts would require mobilizing support not just for a low-income program but also for the revenue increases to pay for it.

- The cuts under a per capita cap would grow substantially over time -- making them harder to undo. That's true for both the destructive House cap and the even more destructive version under consideration by the Senate. Estimates suggest that the long-run cuts to Medicaid from a per capita cap indexed to general inflation, as under the Senate bill, could be several times larger or more than those under the House cap. That difference likely amounts to hundreds of billions of dollars of additional federal cuts in the subsequent decade.[4] As a result, if offsets are needed to undo the Medicaid cuts, they would need to be far larger than those required to undo the past SGR cuts -- and would grow substantially after the current ten-year budget window. Indeed, reversing all of the AHCA's tax breaks wouldn't pay for undoing the Medicaid cuts.

- States would have to plan for cuts in advance -- meaning they'd have no choice but to act pre-emptively, even if Congress eventually mitigated the damage. The magnitude of the cuts under a per capita cap, plus the difficulty of undoing them, would leave states with no choice but to act in advance. Even while lobbying Congress to reverse the cuts, they would pre-emptively limit Medicaid eligibility and services and cut provider payment rates to avoid the possibility that they'd have to drop coverage suddenly if the cuts took effect.[5]

Finally, it's worth noting that the Senate's changes illustrate another serious problem with a per capita cap: it gives policymakers an easy way to make deeper cuts to Medicaid whenever they need budget savings. Just as the Senate dialed down the growth rate of future Medicaid spending in order to meet the AHCA's overall deficit targets, future Congresses would have a strong incentive to make seemingly technical tweaks to the cap that generate large savings by further lowering the growth rate. Indeed, Congress may find it especially appealing to enact cuts that take effect several years down the line in order to offset more immediate costs, as the Senate is effectively doing with its changes.

Thus, while pundits may be right that the bill's Medicaid cuts will unfold differently over time than anticipated today, the cuts would likely end up bigger, not smaller, than those enacted now.

© 2023 Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

Jacob LeibenluftJacob Leibenluft is a senior advisor at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

Despite promises that the emerging Senate health bill will moderate the health coverage cuts in the House-passed American Health Care Act (AHCA), the Senate not only is retaining the House bill's fundamental restructuring of the Medicaid program -- a "per capita cap" on federal funding -- but is deepening the cuts under the per capita cap beginning around 2025.[1] Because the per capita cap wouldn't take effect until 2020 and the Senate's further cuts wouldn't kick in until five years after that, some suggest that policymakers might later undo the per capita cap itself or indefinitely delay the deeper cuts under pressure from state leaders, the public, providers, and others. This confidence is unwarranted; it ignores both recent history and the legislative constraints that would make it difficult or impossible to undo the deep Medicaid cuts.

Those structural changes would create a political dynamic that could lead to even larger cuts in the future. Once Congress both changes Medicaid's basic structure and enacts large annual savings, those cuts are highly unlikely to be reversed. In fact, those structural changes would create a political dynamic that could lead to even larger cuts in the future:

- History suggests that structural changes to Medicaid would be very difficult to reverse. The basic concept behind the per capita cap is to impose a cap on federal funding per beneficiary, replacing the existing commitment of the federal government to pay a fixed share of state Medicaid costs. Experience with other programs suggests that such radical structural changes won't be reversed. The conversion of the Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) entitlement program to the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) block grant in 1996 is instructive: TANF's block grant structure has not only persisted but also led to a continuing erosion of the program's funding and effectiveness.[2]

Indeed, the history of block grants (the closest analogy to a per capita cap) is that this structure enables deep cuts over time. Since 2000, funding for the 13 major housing, health, and social services block grants has fallen by 27 percent, after adjusting for inflation (and 37 percent after adjusting for inflation and population growth).[3]

- Experience shows that spending cuts are also difficult to undo - due to both legislative and political constraints. Commentators have analogized the future increase in the Medicaid cuts to expiring tax provisions or cuts to Medicare payments to physicians under the "sustainable growth rate" (SGR) formula -- measures that threatened sudden and painful cuts or tax increases, which Congress repeatedly delayed and ultimately largely reversed due to their political unpopularity. But recent history suggests that planned spending cuts aren't easy to undo. Unlike expiring tax provisions, both congressional rules and Republican demands may require "pay-fors" to offset the cost of reversing planned spending cuts. To reverse the spending cuts without offsetting the cost would likely require support from congressional leadership in both houses, 60 votes in the Senate, and support from the President.

Indeed, while canceling the planned SGR cuts was highly popular and supported by a vocal and powerful interest group, for nearly 20 years -- almost without exception -- Congress either offset the cuts with other cuts (frequently other health cuts) or let them take effect. The automatic "sequestration" cuts passed in 2011 to force further deficit reduction are another example: a significant share of the cuts have taken effect, and sequestration relief has required substantial offsets.

Reversing Medicaid cuts would require both a political consensus that they shouldn't have been enacted and sufficient congressional support to either waive budget rules or find painful offsets to achieve them. To be sure, Medicaid has broad-based support and affects a wide range of seniors, people with disabilities, and families with children. But reversing these cuts would require mobilizing support not just for a low-income program but also for the revenue increases to pay for it.

- The cuts under a per capita cap would grow substantially over time -- making them harder to undo. That's true for both the destructive House cap and the even more destructive version under consideration by the Senate. Estimates suggest that the long-run cuts to Medicaid from a per capita cap indexed to general inflation, as under the Senate bill, could be several times larger or more than those under the House cap. That difference likely amounts to hundreds of billions of dollars of additional federal cuts in the subsequent decade.[4] As a result, if offsets are needed to undo the Medicaid cuts, they would need to be far larger than those required to undo the past SGR cuts -- and would grow substantially after the current ten-year budget window. Indeed, reversing all of the AHCA's tax breaks wouldn't pay for undoing the Medicaid cuts.

- States would have to plan for cuts in advance -- meaning they'd have no choice but to act pre-emptively, even if Congress eventually mitigated the damage. The magnitude of the cuts under a per capita cap, plus the difficulty of undoing them, would leave states with no choice but to act in advance. Even while lobbying Congress to reverse the cuts, they would pre-emptively limit Medicaid eligibility and services and cut provider payment rates to avoid the possibility that they'd have to drop coverage suddenly if the cuts took effect.[5]

Finally, it's worth noting that the Senate's changes illustrate another serious problem with a per capita cap: it gives policymakers an easy way to make deeper cuts to Medicaid whenever they need budget savings. Just as the Senate dialed down the growth rate of future Medicaid spending in order to meet the AHCA's overall deficit targets, future Congresses would have a strong incentive to make seemingly technical tweaks to the cap that generate large savings by further lowering the growth rate. Indeed, Congress may find it especially appealing to enact cuts that take effect several years down the line in order to offset more immediate costs, as the Senate is effectively doing with its changes.

Thus, while pundits may be right that the bill's Medicaid cuts will unfold differently over time than anticipated today, the cuts would likely end up bigger, not smaller, than those enacted now.