SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

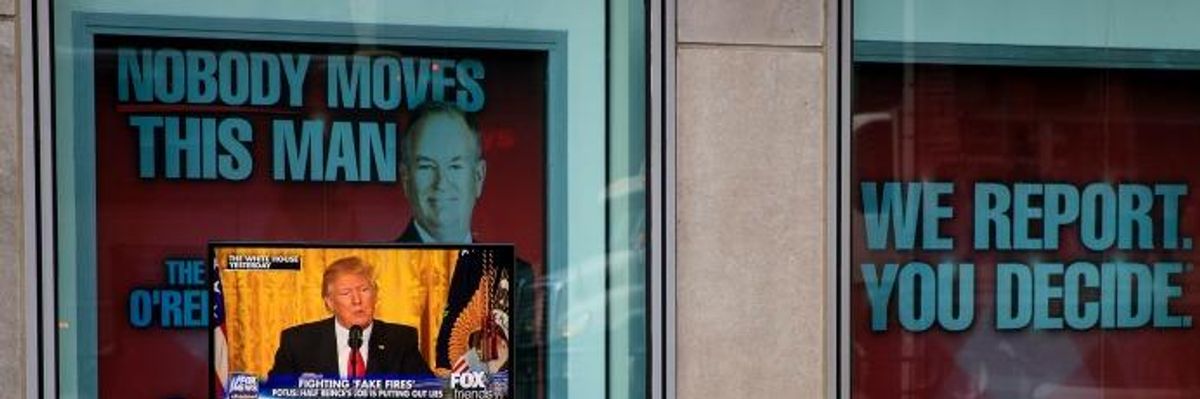

A clip of President Donald Trump's Thursday press conference is played on 'Fox And Friends', seen on a monitor outside of the Fox News studios, on February 17, 2017 in New York City. President Trump, a frequent consumer and critic of cable news, recently tweeted that Fox and Friends is 'great'. (Photo: Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

Political pundits have been intoxicated lately by explanations as to why Democrats always seem to be behind the eight ball -- never mind that Hillary Clinton won the popular vote; that liberal positions on issues like health care, climate change and income inequality are held by a majority of Americans; or that Republicans are more unpopular.

The idea, promoted in The New York Times with three different op-eds in the past month alone, is that Democrats don't plug into traditional American values the way Republicans do, and it's those values that swayed the last presidential election, especially in the Rust Belt, and in the recent special congressional elections, Trump's general unpopularity notwithstanding.

Daniel K. Williams, a religious historian, attributed the Democrats' recent loss in Georgia's 6th Congressional District to the fact that the party had become too secular to appeal to religious minorities and baby boomers, too removed from America's religious traditions.

Democratic pollster Mark Penn and former Manhattan borough president Andrew Stein penned an op-ed in which they called for the Democrats to reject the "siren calls of the left" and move to the center to attract working-class voters "who feel abandoned by the party's shift away from moderate positions on trade and immigration, from backing police and tough anti-crime measures, from trying to restore manufacturing jobs." In short, Republicanism lite.

And then there is the analysis of Times columnist David Brooks, inaptly titled "What's the Matter With Republicans?" because it really was aimed at what's wrong with Democrats, since in his view nothing really seems to be wrong with the GOP. Republicans subscribe to traditional American values forged on the frontier, things like self-reliance and self-sufficiency, independence, loyalty, toughness and virtue; Democrats seemingly do not.

None of these criticisms is new. In fact, they are pretty hoary. But they actually seem a lot less persuasive now that Donald Trump is in the White House. There has never been a president whose values are so antithetical to traditional American ones -- never one less self-reliant, loyal, tough, disciplined, religious or virtuous -- so the argument doesn't hold much water to me.

I want to suggest something else entirely that helps explain the love for Republicans and Trump in the supposedly old-fashioned precincts of the South, Midwest and West. I want to suggest that beneath or beside these so-called "traditional" frontier values -- which we ourselves promote so self-aggrandizingly -- there's another set of values, no less American, and probably much more so. According to some historians, they, too, were forged on the frontier as a form of survival.

They have nothing to do with the Protestant ethic -- quite the contrary. They are not values of virtue but of success, promoting deception and the fast con, easy cash, hustling and the love of money. If the first set of values might be called "Algeresque," after Horatio Alger, the popular 19th-century American author who wrote stories about poor ragamuffins rising to great wealth through hard work, this second set might be called "Barnumesque," after P. T. Barnum, the 19th-century promoter, hoaxster and circus impresario, who played on his countrymen's gullibility.

As Michael Winship wrote on this site recently in astutely pointing to Trump's hucksterism, Trump is a chip off of P.T. Barnum's block. I'd like to focus here on something else: Unfortunately, he isn't the only one. For all our pieties about the benefits of hard work and decency, this is far more Barnum's country than Alger's, which may be the Democrats' real problem. If anything, they are too virtuous for their own good, too beholden to moral values.

Of course, no one wants to come right out and say that America is a land of hustlers, least of all politicians and pundits. It is a kind of sacrilege. Everyone prefers the Alger scenario of social mobility, which historian Henry Steele Commager described as one in which "opportunities lie all about you; success is material and is the reward of virtue and work." This is one of the bulwarks of America. To say otherwise is to engage in class warfare, and class warfare, we are often told by conservatives, is a betrayal of American exceptionalism.

But as much a bulwark as this is, just about everyone also knows it isn't exactly true -- even, it turns out, Horatio Alger himself. "He constantly preached that success was to be won through virtue and hard work," writes his most perspicacious biographer, John Tebbel, "but his stories tell us just as constantly that success is actually the result of fortuitous circumstance." Or luck, so long as you aren't lucky enough to be born rich. Those idlers -- the Trumps of the world -- are Alger's villains.

Perhaps it was because the American dream was so riddled with inconsistencies, contradictions and outright lies that Americans constructed (and lived) an alternative in which success goes not to the industrious but to the insolent. This is the thesis of historian Walter McDougall's provocative story of the early republic, Freedom Just Around the Corner. As he writes, it is the unexceptionalism of so many Americans that really makes America exceptional.

"To suggest that Americans are, among other things, prone to be hustlers," McDougall notes, "is simply to acknowledge Americans have enjoyed more opportunity to pursue their ambitions by foul means or fair, than any other people in history." And: "Americans take it for granted that 'everyone's got an angle,' except maybe themselves." This idea, that you succeed through grift and guile, has made many Americans more cynical than idealistic, more Barnum than Alger, and, yes, more Trump than Obama.

Barnum understood the financial implications of the swindle. He was a brilliant self-promoter and ballyhoo artist who sold an unsuspecting public on things like seeing George Washington's 160-year-old nurse, or an "authentic" stuffed mermaid, and then made additional money by exposing his own frauds, realizing that people actually liked being fooled and being debriefed on the foolery. In this, he was merely a progenitor of what would be a long string of knaves, cheats, con artists and rascals who became an American type and who later turned the heist movie into an American staple. Virtuous heroes were dull. These rapscallions weren't, and it wasn't lost on most Americans that these con men were subverting those hallowed values David Brooks celebrates.

But as evident as the financial rewards were, it has taken a long time for anyone to see the political implications of the hustle, and now Trump has. He prides himself on not having earned his wealth, on his serial bankruptcies, on stiffing contractors and on gaming the tax system, the last three of which he regards as just clever business. Even his hint of having taped his conversations with former FBI director James Comey was a form of deceit.

Many of us, myself included, wondered why this didn't bring him public scorn and create not just a credibility gap but a credibility canyon, but that's because, as political observers, we were working from the traditional values manual and not the subversive one. I suspect, for all that platitudinous op-ed nonsense about the attraction of traditional values, this is a very real source of Trump's appeal, as it is of the Republicans'.

Working within this other tradition, Trump makes no bones about being a hustler. He is shameless. Some people admire that. The Republicans, for their part, give lip service to virtue and are as self-righteous as they come, but everyone knows they are really about gaming the system, too. This is America the Deceitful. And many Americans like it, I presume because it seems to let them thumb their noses at their supposed social betters, just as Trump has done.

So, while people bemoan the end of moral certitude and a lost halcyon past, Trump the trickster and his Republican henchmen are creating a new America adrift in moral chaos. This, too, has a Barnum antecedent. As Barnum biographer and cultural historian Neil Harris wrote of Barnum's destruction of traditional forms of evidence and authority, "When credentials, coats of arms and university degrees no longer guaranteed what passed for truth, it was difficult to know what to believe. Everything was up for grabs."

Not a bad description of contemporary America. The pundits may say that what ails Democrats is insufficient religiosity or moderation or self-reliance or whatever the cliche happens to be, but in a time of moral turpitude, it may be insufficient rascality that really hurts them.

Trump has gambled that many Americans would enjoy his unpresidential, con-man antics. He hasn't entirely won that gamble. Most Americans don't. But there are enough who do, especially among Republicans, to let him wreak havoc. After all those years of our hearing Algeresque bromides, President Barnum is now in charge, and he is working hard to reveal America as one great big con game.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

Political pundits have been intoxicated lately by explanations as to why Democrats always seem to be behind the eight ball -- never mind that Hillary Clinton won the popular vote; that liberal positions on issues like health care, climate change and income inequality are held by a majority of Americans; or that Republicans are more unpopular.

The idea, promoted in The New York Times with three different op-eds in the past month alone, is that Democrats don't plug into traditional American values the way Republicans do, and it's those values that swayed the last presidential election, especially in the Rust Belt, and in the recent special congressional elections, Trump's general unpopularity notwithstanding.

Daniel K. Williams, a religious historian, attributed the Democrats' recent loss in Georgia's 6th Congressional District to the fact that the party had become too secular to appeal to religious minorities and baby boomers, too removed from America's religious traditions.

Democratic pollster Mark Penn and former Manhattan borough president Andrew Stein penned an op-ed in which they called for the Democrats to reject the "siren calls of the left" and move to the center to attract working-class voters "who feel abandoned by the party's shift away from moderate positions on trade and immigration, from backing police and tough anti-crime measures, from trying to restore manufacturing jobs." In short, Republicanism lite.

And then there is the analysis of Times columnist David Brooks, inaptly titled "What's the Matter With Republicans?" because it really was aimed at what's wrong with Democrats, since in his view nothing really seems to be wrong with the GOP. Republicans subscribe to traditional American values forged on the frontier, things like self-reliance and self-sufficiency, independence, loyalty, toughness and virtue; Democrats seemingly do not.

None of these criticisms is new. In fact, they are pretty hoary. But they actually seem a lot less persuasive now that Donald Trump is in the White House. There has never been a president whose values are so antithetical to traditional American ones -- never one less self-reliant, loyal, tough, disciplined, religious or virtuous -- so the argument doesn't hold much water to me.

I want to suggest something else entirely that helps explain the love for Republicans and Trump in the supposedly old-fashioned precincts of the South, Midwest and West. I want to suggest that beneath or beside these so-called "traditional" frontier values -- which we ourselves promote so self-aggrandizingly -- there's another set of values, no less American, and probably much more so. According to some historians, they, too, were forged on the frontier as a form of survival.

They have nothing to do with the Protestant ethic -- quite the contrary. They are not values of virtue but of success, promoting deception and the fast con, easy cash, hustling and the love of money. If the first set of values might be called "Algeresque," after Horatio Alger, the popular 19th-century American author who wrote stories about poor ragamuffins rising to great wealth through hard work, this second set might be called "Barnumesque," after P. T. Barnum, the 19th-century promoter, hoaxster and circus impresario, who played on his countrymen's gullibility.

As Michael Winship wrote on this site recently in astutely pointing to Trump's hucksterism, Trump is a chip off of P.T. Barnum's block. I'd like to focus here on something else: Unfortunately, he isn't the only one. For all our pieties about the benefits of hard work and decency, this is far more Barnum's country than Alger's, which may be the Democrats' real problem. If anything, they are too virtuous for their own good, too beholden to moral values.

Of course, no one wants to come right out and say that America is a land of hustlers, least of all politicians and pundits. It is a kind of sacrilege. Everyone prefers the Alger scenario of social mobility, which historian Henry Steele Commager described as one in which "opportunities lie all about you; success is material and is the reward of virtue and work." This is one of the bulwarks of America. To say otherwise is to engage in class warfare, and class warfare, we are often told by conservatives, is a betrayal of American exceptionalism.

But as much a bulwark as this is, just about everyone also knows it isn't exactly true -- even, it turns out, Horatio Alger himself. "He constantly preached that success was to be won through virtue and hard work," writes his most perspicacious biographer, John Tebbel, "but his stories tell us just as constantly that success is actually the result of fortuitous circumstance." Or luck, so long as you aren't lucky enough to be born rich. Those idlers -- the Trumps of the world -- are Alger's villains.

Perhaps it was because the American dream was so riddled with inconsistencies, contradictions and outright lies that Americans constructed (and lived) an alternative in which success goes not to the industrious but to the insolent. This is the thesis of historian Walter McDougall's provocative story of the early republic, Freedom Just Around the Corner. As he writes, it is the unexceptionalism of so many Americans that really makes America exceptional.

"To suggest that Americans are, among other things, prone to be hustlers," McDougall notes, "is simply to acknowledge Americans have enjoyed more opportunity to pursue their ambitions by foul means or fair, than any other people in history." And: "Americans take it for granted that 'everyone's got an angle,' except maybe themselves." This idea, that you succeed through grift and guile, has made many Americans more cynical than idealistic, more Barnum than Alger, and, yes, more Trump than Obama.

Barnum understood the financial implications of the swindle. He was a brilliant self-promoter and ballyhoo artist who sold an unsuspecting public on things like seeing George Washington's 160-year-old nurse, or an "authentic" stuffed mermaid, and then made additional money by exposing his own frauds, realizing that people actually liked being fooled and being debriefed on the foolery. In this, he was merely a progenitor of what would be a long string of knaves, cheats, con artists and rascals who became an American type and who later turned the heist movie into an American staple. Virtuous heroes were dull. These rapscallions weren't, and it wasn't lost on most Americans that these con men were subverting those hallowed values David Brooks celebrates.

But as evident as the financial rewards were, it has taken a long time for anyone to see the political implications of the hustle, and now Trump has. He prides himself on not having earned his wealth, on his serial bankruptcies, on stiffing contractors and on gaming the tax system, the last three of which he regards as just clever business. Even his hint of having taped his conversations with former FBI director James Comey was a form of deceit.

Many of us, myself included, wondered why this didn't bring him public scorn and create not just a credibility gap but a credibility canyon, but that's because, as political observers, we were working from the traditional values manual and not the subversive one. I suspect, for all that platitudinous op-ed nonsense about the attraction of traditional values, this is a very real source of Trump's appeal, as it is of the Republicans'.

Working within this other tradition, Trump makes no bones about being a hustler. He is shameless. Some people admire that. The Republicans, for their part, give lip service to virtue and are as self-righteous as they come, but everyone knows they are really about gaming the system, too. This is America the Deceitful. And many Americans like it, I presume because it seems to let them thumb their noses at their supposed social betters, just as Trump has done.

So, while people bemoan the end of moral certitude and a lost halcyon past, Trump the trickster and his Republican henchmen are creating a new America adrift in moral chaos. This, too, has a Barnum antecedent. As Barnum biographer and cultural historian Neil Harris wrote of Barnum's destruction of traditional forms of evidence and authority, "When credentials, coats of arms and university degrees no longer guaranteed what passed for truth, it was difficult to know what to believe. Everything was up for grabs."

Not a bad description of contemporary America. The pundits may say that what ails Democrats is insufficient religiosity or moderation or self-reliance or whatever the cliche happens to be, but in a time of moral turpitude, it may be insufficient rascality that really hurts them.

Trump has gambled that many Americans would enjoy his unpresidential, con-man antics. He hasn't entirely won that gamble. Most Americans don't. But there are enough who do, especially among Republicans, to let him wreak havoc. After all those years of our hearing Algeresque bromides, President Barnum is now in charge, and he is working hard to reveal America as one great big con game.

Political pundits have been intoxicated lately by explanations as to why Democrats always seem to be behind the eight ball -- never mind that Hillary Clinton won the popular vote; that liberal positions on issues like health care, climate change and income inequality are held by a majority of Americans; or that Republicans are more unpopular.

The idea, promoted in The New York Times with three different op-eds in the past month alone, is that Democrats don't plug into traditional American values the way Republicans do, and it's those values that swayed the last presidential election, especially in the Rust Belt, and in the recent special congressional elections, Trump's general unpopularity notwithstanding.

Daniel K. Williams, a religious historian, attributed the Democrats' recent loss in Georgia's 6th Congressional District to the fact that the party had become too secular to appeal to religious minorities and baby boomers, too removed from America's religious traditions.

Democratic pollster Mark Penn and former Manhattan borough president Andrew Stein penned an op-ed in which they called for the Democrats to reject the "siren calls of the left" and move to the center to attract working-class voters "who feel abandoned by the party's shift away from moderate positions on trade and immigration, from backing police and tough anti-crime measures, from trying to restore manufacturing jobs." In short, Republicanism lite.

And then there is the analysis of Times columnist David Brooks, inaptly titled "What's the Matter With Republicans?" because it really was aimed at what's wrong with Democrats, since in his view nothing really seems to be wrong with the GOP. Republicans subscribe to traditional American values forged on the frontier, things like self-reliance and self-sufficiency, independence, loyalty, toughness and virtue; Democrats seemingly do not.

None of these criticisms is new. In fact, they are pretty hoary. But they actually seem a lot less persuasive now that Donald Trump is in the White House. There has never been a president whose values are so antithetical to traditional American ones -- never one less self-reliant, loyal, tough, disciplined, religious or virtuous -- so the argument doesn't hold much water to me.

I want to suggest something else entirely that helps explain the love for Republicans and Trump in the supposedly old-fashioned precincts of the South, Midwest and West. I want to suggest that beneath or beside these so-called "traditional" frontier values -- which we ourselves promote so self-aggrandizingly -- there's another set of values, no less American, and probably much more so. According to some historians, they, too, were forged on the frontier as a form of survival.

They have nothing to do with the Protestant ethic -- quite the contrary. They are not values of virtue but of success, promoting deception and the fast con, easy cash, hustling and the love of money. If the first set of values might be called "Algeresque," after Horatio Alger, the popular 19th-century American author who wrote stories about poor ragamuffins rising to great wealth through hard work, this second set might be called "Barnumesque," after P. T. Barnum, the 19th-century promoter, hoaxster and circus impresario, who played on his countrymen's gullibility.

As Michael Winship wrote on this site recently in astutely pointing to Trump's hucksterism, Trump is a chip off of P.T. Barnum's block. I'd like to focus here on something else: Unfortunately, he isn't the only one. For all our pieties about the benefits of hard work and decency, this is far more Barnum's country than Alger's, which may be the Democrats' real problem. If anything, they are too virtuous for their own good, too beholden to moral values.

Of course, no one wants to come right out and say that America is a land of hustlers, least of all politicians and pundits. It is a kind of sacrilege. Everyone prefers the Alger scenario of social mobility, which historian Henry Steele Commager described as one in which "opportunities lie all about you; success is material and is the reward of virtue and work." This is one of the bulwarks of America. To say otherwise is to engage in class warfare, and class warfare, we are often told by conservatives, is a betrayal of American exceptionalism.

But as much a bulwark as this is, just about everyone also knows it isn't exactly true -- even, it turns out, Horatio Alger himself. "He constantly preached that success was to be won through virtue and hard work," writes his most perspicacious biographer, John Tebbel, "but his stories tell us just as constantly that success is actually the result of fortuitous circumstance." Or luck, so long as you aren't lucky enough to be born rich. Those idlers -- the Trumps of the world -- are Alger's villains.

Perhaps it was because the American dream was so riddled with inconsistencies, contradictions and outright lies that Americans constructed (and lived) an alternative in which success goes not to the industrious but to the insolent. This is the thesis of historian Walter McDougall's provocative story of the early republic, Freedom Just Around the Corner. As he writes, it is the unexceptionalism of so many Americans that really makes America exceptional.

"To suggest that Americans are, among other things, prone to be hustlers," McDougall notes, "is simply to acknowledge Americans have enjoyed more opportunity to pursue their ambitions by foul means or fair, than any other people in history." And: "Americans take it for granted that 'everyone's got an angle,' except maybe themselves." This idea, that you succeed through grift and guile, has made many Americans more cynical than idealistic, more Barnum than Alger, and, yes, more Trump than Obama.

Barnum understood the financial implications of the swindle. He was a brilliant self-promoter and ballyhoo artist who sold an unsuspecting public on things like seeing George Washington's 160-year-old nurse, or an "authentic" stuffed mermaid, and then made additional money by exposing his own frauds, realizing that people actually liked being fooled and being debriefed on the foolery. In this, he was merely a progenitor of what would be a long string of knaves, cheats, con artists and rascals who became an American type and who later turned the heist movie into an American staple. Virtuous heroes were dull. These rapscallions weren't, and it wasn't lost on most Americans that these con men were subverting those hallowed values David Brooks celebrates.

But as evident as the financial rewards were, it has taken a long time for anyone to see the political implications of the hustle, and now Trump has. He prides himself on not having earned his wealth, on his serial bankruptcies, on stiffing contractors and on gaming the tax system, the last three of which he regards as just clever business. Even his hint of having taped his conversations with former FBI director James Comey was a form of deceit.

Many of us, myself included, wondered why this didn't bring him public scorn and create not just a credibility gap but a credibility canyon, but that's because, as political observers, we were working from the traditional values manual and not the subversive one. I suspect, for all that platitudinous op-ed nonsense about the attraction of traditional values, this is a very real source of Trump's appeal, as it is of the Republicans'.

Working within this other tradition, Trump makes no bones about being a hustler. He is shameless. Some people admire that. The Republicans, for their part, give lip service to virtue and are as self-righteous as they come, but everyone knows they are really about gaming the system, too. This is America the Deceitful. And many Americans like it, I presume because it seems to let them thumb their noses at their supposed social betters, just as Trump has done.

So, while people bemoan the end of moral certitude and a lost halcyon past, Trump the trickster and his Republican henchmen are creating a new America adrift in moral chaos. This, too, has a Barnum antecedent. As Barnum biographer and cultural historian Neil Harris wrote of Barnum's destruction of traditional forms of evidence and authority, "When credentials, coats of arms and university degrees no longer guaranteed what passed for truth, it was difficult to know what to believe. Everything was up for grabs."

Not a bad description of contemporary America. The pundits may say that what ails Democrats is insufficient religiosity or moderation or self-reliance or whatever the cliche happens to be, but in a time of moral turpitude, it may be insufficient rascality that really hurts them.

Trump has gambled that many Americans would enjoy his unpresidential, con-man antics. He hasn't entirely won that gamble. Most Americans don't. But there are enough who do, especially among Republicans, to let him wreak havoc. After all those years of our hearing Algeresque bromides, President Barnum is now in charge, and he is working hard to reveal America as one great big con game.