SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

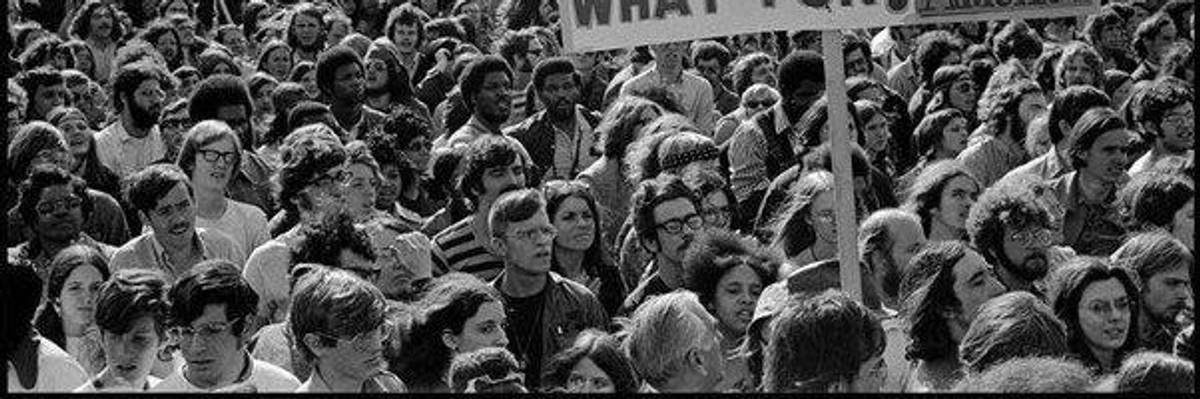

For decades, major news organizations have been taken to task before for giving voice to stories of denigrated veterans without tangible evidence. And yet it persists. (Photo: Quora/Wikimedia)

Stories of Vietnam veterans treated badly by war protesters proliferated in the years surrounding the Persian Gulf War of 1991. They were the inspiration for the "yellow ribbon campaign" intended to signal that Gulf War veterans would be treated differently. My book inquiring into the origins and veracity of the stories about disparaged Vietnam veterans came out in 1998. Little did I imagine at the time that, 20 years later, versions of the same stories would be figuring in remembrances appearing upon the 50th anniversaries of some important dates of the war in Vietnam.

The stories have reappeared, prominently, in the June 20 New York Times and the July 16 Washington Post. The Times piece was written by veteran Bill Reynolds who recounted his experience as an infantryman in a bloody Mekong Delta battle in 1967. Reynolds ended the account with the claim that he, "came home through San Francisco's airport to throngs of hippies harassing me." The Post story reported on a preview screening Ken Burns' forthcoming documentary on the war in Vietnam. Following the screening, veteran David Hagerman told Associated Press reporter Holly Ramer that his reception at the Seattle airport was so negative that he "walked into the nearest men's room, took off my uniform, and threw it in the trash."

Reynolds's story strains belief. Civilian airlines brought troops back from Vietnam but they landed at military airbases like Travis. And there are no news reports or photographs from the war years that document his memory that "throngs of hippies" greeted veterans. Hagerman's memory also raises eyebrows: the abandonment of military property--his uniform--was a serious offense. And despite the numerous versions of this story that circulate, there is no evidence such as photographs of bathroom trash cans draped with uniforms to support the claims. Military personnel had to be in uniform to fly home free making it additionally unlikely that uniforms were shed in the manner described.

Major news organizations have been taken to task before for giving voice to stories of denigrated veterans without tangible evidence. When the 25th anniversary of the war's end was marked in 2000, a spate of them garnered similar press attention. News critic Jack Shafer then editor of "The Fray" at Slate criticized the Times and U.S. News and World Report for their reports, respectively that Vietnam veterans had been spat on by protesters and had had to abandon their military clothing to avoid harassment.

When President Barak Obama spoke on Memorial Day, 2012 he recalled that Vietnam veterans had been "denigrated" upon their return home. "It was a national shame," he said, "that should have never happened." The President went on to pledge that the current generation of veterans would be treated better. The next day, Los Angeles Times editor Michael McGough criticized the president for having "ratified the meme of spat-upon veterans"--an edifying myth, McGough said, but still a myth.

The questionable accuracy of the hostile-homecoming stories is suggested by data from those times. A 1971 survey by Harris Associates conducted for the U.S. Senate reported 94% of the veterans polled saying their reception from their age-group peers was friendly.

The problem with repeating these stories of doubtful truth goes beyond the credibility of the journalism itself. It is rather, the power of the stories to displace the public memory of the war itself and the nature of the opposition to it. The response to Reynolds' article in the Times is a case in point: of the 159 online comments, 48 or 30% focused on just 13 of the 1,500 words that he had written: "I came home through San Francisco's airport to throngs of hippies harassing me." Many more of the comments were of the "thank you for your service" variety that are meaningful only with the backstory of supposedly hostile homecomings as context.

Most importantly, the war that Reynolds had written about, and we need to think about, was occluded by his veteran-as-victim anecdote, a storyline that readers could not resist.

The stories of Vietnam veterans defiled by activists has worked over the years to vilify the anti-war movement and even discredit the many veterans who joined the cause to end the war. The stories fed a belief that the war had been lost on the home front; from the 1980s through the 2016 election, conservative politicians ran for office on a conviction that radicals on campuses and liberals in Congress had sapped American will to win in Vietnam; it is the wellspring of the resentfulness that Donald Trump tapped for his run to the White House.

President Obama's 2012 Memorial Day speech announcing Pentagon funding for a twelve-year series of Vietnam War anniversary commemorations renewed interest in the war and made the treatment of veterans the focus of that interest. Ken Burns' film due out in September will keep the war in our conversations.

News coverage of the commemorations and the film will magnify those interests. Let's hope that news coverage of the remembrances and reception to the film will temper the alluring but dubious reports of unfriendly veteran homecomings with references to more historically grounded research.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Stories of Vietnam veterans treated badly by war protesters proliferated in the years surrounding the Persian Gulf War of 1991. They were the inspiration for the "yellow ribbon campaign" intended to signal that Gulf War veterans would be treated differently. My book inquiring into the origins and veracity of the stories about disparaged Vietnam veterans came out in 1998. Little did I imagine at the time that, 20 years later, versions of the same stories would be figuring in remembrances appearing upon the 50th anniversaries of some important dates of the war in Vietnam.

The stories have reappeared, prominently, in the June 20 New York Times and the July 16 Washington Post. The Times piece was written by veteran Bill Reynolds who recounted his experience as an infantryman in a bloody Mekong Delta battle in 1967. Reynolds ended the account with the claim that he, "came home through San Francisco's airport to throngs of hippies harassing me." The Post story reported on a preview screening Ken Burns' forthcoming documentary on the war in Vietnam. Following the screening, veteran David Hagerman told Associated Press reporter Holly Ramer that his reception at the Seattle airport was so negative that he "walked into the nearest men's room, took off my uniform, and threw it in the trash."

Reynolds's story strains belief. Civilian airlines brought troops back from Vietnam but they landed at military airbases like Travis. And there are no news reports or photographs from the war years that document his memory that "throngs of hippies" greeted veterans. Hagerman's memory also raises eyebrows: the abandonment of military property--his uniform--was a serious offense. And despite the numerous versions of this story that circulate, there is no evidence such as photographs of bathroom trash cans draped with uniforms to support the claims. Military personnel had to be in uniform to fly home free making it additionally unlikely that uniforms were shed in the manner described.

Major news organizations have been taken to task before for giving voice to stories of denigrated veterans without tangible evidence. When the 25th anniversary of the war's end was marked in 2000, a spate of them garnered similar press attention. News critic Jack Shafer then editor of "The Fray" at Slate criticized the Times and U.S. News and World Report for their reports, respectively that Vietnam veterans had been spat on by protesters and had had to abandon their military clothing to avoid harassment.

When President Barak Obama spoke on Memorial Day, 2012 he recalled that Vietnam veterans had been "denigrated" upon their return home. "It was a national shame," he said, "that should have never happened." The President went on to pledge that the current generation of veterans would be treated better. The next day, Los Angeles Times editor Michael McGough criticized the president for having "ratified the meme of spat-upon veterans"--an edifying myth, McGough said, but still a myth.

The questionable accuracy of the hostile-homecoming stories is suggested by data from those times. A 1971 survey by Harris Associates conducted for the U.S. Senate reported 94% of the veterans polled saying their reception from their age-group peers was friendly.

The problem with repeating these stories of doubtful truth goes beyond the credibility of the journalism itself. It is rather, the power of the stories to displace the public memory of the war itself and the nature of the opposition to it. The response to Reynolds' article in the Times is a case in point: of the 159 online comments, 48 or 30% focused on just 13 of the 1,500 words that he had written: "I came home through San Francisco's airport to throngs of hippies harassing me." Many more of the comments were of the "thank you for your service" variety that are meaningful only with the backstory of supposedly hostile homecomings as context.

Most importantly, the war that Reynolds had written about, and we need to think about, was occluded by his veteran-as-victim anecdote, a storyline that readers could not resist.

The stories of Vietnam veterans defiled by activists has worked over the years to vilify the anti-war movement and even discredit the many veterans who joined the cause to end the war. The stories fed a belief that the war had been lost on the home front; from the 1980s through the 2016 election, conservative politicians ran for office on a conviction that radicals on campuses and liberals in Congress had sapped American will to win in Vietnam; it is the wellspring of the resentfulness that Donald Trump tapped for his run to the White House.

President Obama's 2012 Memorial Day speech announcing Pentagon funding for a twelve-year series of Vietnam War anniversary commemorations renewed interest in the war and made the treatment of veterans the focus of that interest. Ken Burns' film due out in September will keep the war in our conversations.

News coverage of the commemorations and the film will magnify those interests. Let's hope that news coverage of the remembrances and reception to the film will temper the alluring but dubious reports of unfriendly veteran homecomings with references to more historically grounded research.

Stories of Vietnam veterans treated badly by war protesters proliferated in the years surrounding the Persian Gulf War of 1991. They were the inspiration for the "yellow ribbon campaign" intended to signal that Gulf War veterans would be treated differently. My book inquiring into the origins and veracity of the stories about disparaged Vietnam veterans came out in 1998. Little did I imagine at the time that, 20 years later, versions of the same stories would be figuring in remembrances appearing upon the 50th anniversaries of some important dates of the war in Vietnam.

The stories have reappeared, prominently, in the June 20 New York Times and the July 16 Washington Post. The Times piece was written by veteran Bill Reynolds who recounted his experience as an infantryman in a bloody Mekong Delta battle in 1967. Reynolds ended the account with the claim that he, "came home through San Francisco's airport to throngs of hippies harassing me." The Post story reported on a preview screening Ken Burns' forthcoming documentary on the war in Vietnam. Following the screening, veteran David Hagerman told Associated Press reporter Holly Ramer that his reception at the Seattle airport was so negative that he "walked into the nearest men's room, took off my uniform, and threw it in the trash."

Reynolds's story strains belief. Civilian airlines brought troops back from Vietnam but they landed at military airbases like Travis. And there are no news reports or photographs from the war years that document his memory that "throngs of hippies" greeted veterans. Hagerman's memory also raises eyebrows: the abandonment of military property--his uniform--was a serious offense. And despite the numerous versions of this story that circulate, there is no evidence such as photographs of bathroom trash cans draped with uniforms to support the claims. Military personnel had to be in uniform to fly home free making it additionally unlikely that uniforms were shed in the manner described.

Major news organizations have been taken to task before for giving voice to stories of denigrated veterans without tangible evidence. When the 25th anniversary of the war's end was marked in 2000, a spate of them garnered similar press attention. News critic Jack Shafer then editor of "The Fray" at Slate criticized the Times and U.S. News and World Report for their reports, respectively that Vietnam veterans had been spat on by protesters and had had to abandon their military clothing to avoid harassment.

When President Barak Obama spoke on Memorial Day, 2012 he recalled that Vietnam veterans had been "denigrated" upon their return home. "It was a national shame," he said, "that should have never happened." The President went on to pledge that the current generation of veterans would be treated better. The next day, Los Angeles Times editor Michael McGough criticized the president for having "ratified the meme of spat-upon veterans"--an edifying myth, McGough said, but still a myth.

The questionable accuracy of the hostile-homecoming stories is suggested by data from those times. A 1971 survey by Harris Associates conducted for the U.S. Senate reported 94% of the veterans polled saying their reception from their age-group peers was friendly.

The problem with repeating these stories of doubtful truth goes beyond the credibility of the journalism itself. It is rather, the power of the stories to displace the public memory of the war itself and the nature of the opposition to it. The response to Reynolds' article in the Times is a case in point: of the 159 online comments, 48 or 30% focused on just 13 of the 1,500 words that he had written: "I came home through San Francisco's airport to throngs of hippies harassing me." Many more of the comments were of the "thank you for your service" variety that are meaningful only with the backstory of supposedly hostile homecomings as context.

Most importantly, the war that Reynolds had written about, and we need to think about, was occluded by his veteran-as-victim anecdote, a storyline that readers could not resist.

The stories of Vietnam veterans defiled by activists has worked over the years to vilify the anti-war movement and even discredit the many veterans who joined the cause to end the war. The stories fed a belief that the war had been lost on the home front; from the 1980s through the 2016 election, conservative politicians ran for office on a conviction that radicals on campuses and liberals in Congress had sapped American will to win in Vietnam; it is the wellspring of the resentfulness that Donald Trump tapped for his run to the White House.

President Obama's 2012 Memorial Day speech announcing Pentagon funding for a twelve-year series of Vietnam War anniversary commemorations renewed interest in the war and made the treatment of veterans the focus of that interest. Ken Burns' film due out in September will keep the war in our conversations.

News coverage of the commemorations and the film will magnify those interests. Let's hope that news coverage of the remembrances and reception to the film will temper the alluring but dubious reports of unfriendly veteran homecomings with references to more historically grounded research.