Cross-posted from USA Today.

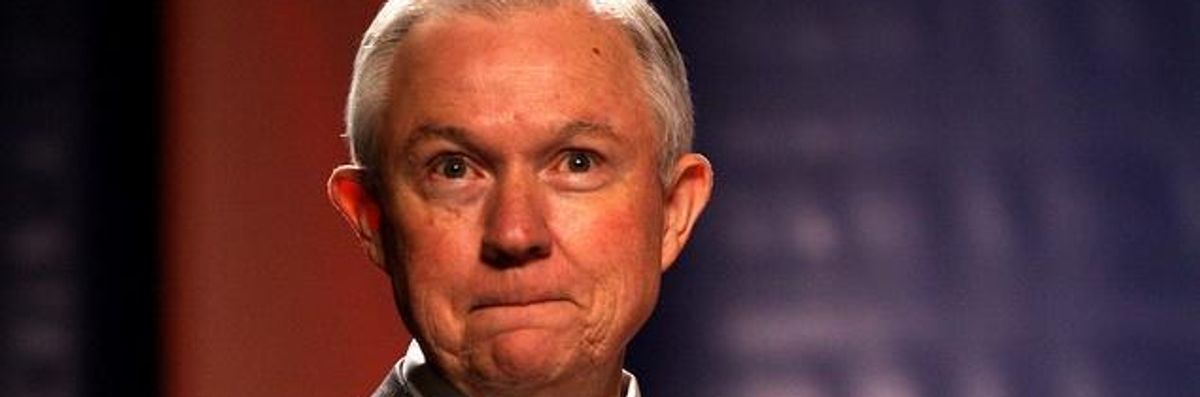

Attorney General Jeff Sessions has reportedly received word from new White House chief of staff John Kelly that his job is safe. That was good news following President Trump's hints that he planned to replace Sessions with someone who would not recuse from the Justice Department's Trump-Russia investigation.

Such a move would sow doubt in the investigation's outcome and imperil the public's faith in the administration of justice. Simply put, the investigation must continue without real or perceived political interference.

Yet Trump's recent public haranguing of Sessions for recusing himself from the Trump-Russia investigation has been alarming enough. In the 2017 version of his campaign's "lock her up" chant, Trump took to Twitter complaining that Sessions hadn't done enough to investigate "Hillary Clinton crimes" -- another investigation from which Sessions has removed himself.

As both Republicans and Democrats have recognized, Sessions made exactly the right call in formally stepping back from these investigations.

Sessions had no choice but to recuse. And that's not just because of his two meetings with Russian Ambassador Kisilyak, which created an appearance of impropriety after he misled the Senate Judiciary Committee. A Justice Department rule prohibits employees from taking part in an investigation if they have "a personal or political relationship" with anyone who was involved in the investigation or would be affected by it. "Close identification with an elected official, a candidate . . . a political party, or a campaign" is explicitly listed as an example of the type of political relationship that would require recusal. There can be no doubt that Sessions -- as the first senator to back Trump's presidential aspirations and as a member of the Trump campaign's national security advisory council -- fits the bill.

The Justice Department rule is no technical nicety. It embodies fundamental principles of fairness that are the bedrock of our democracy.

In Federalist 10, James Madison famously noted: "no man is allowed to be a judge in his own cause, because his interest would certainly bias his judgment, and, not improbably, corrupt his integrity." This principle applies to criminal investigations - a person with an interest in the outcome of the inquiry cannot be expected to be neutral in examining the facts and coming to conclusions. Their views would inevitably be colored by how the investigation would affect them and those with whom they have relationships.

It is easily understood in the context of everyday crimes -- a witness or suspect in a fraud investigation would never supervise the inquiry, just as they should not serve as a juror or judge in the case. Otherwise, the results would not carry any legitimacy.

When it comes to the Attorney General, this imperative is even stronger: He must ensure not only that justice is done, but that justice is seen to be done. The Attorney General sits atop the formidable federal law enforcement apparatus. All 93 U.S. Attorneys and their staffs and thousands of FBI agents come under his authority. If he is seen to be using these resources to advance the cause of one political faction over another, he will undermine faith in the principle that the United States is a country ruled by law.

Despite Trump's protests to the contrary, an Attorney General's decision to remove himself from an investigation is not breaking news. Former Attorneys General from both parties have done the same. In 2003, Attorney General John Ashcroft recused himself from the investigation into the leak of the identity of Valerie Plame, a former undercover CIA officer. President Bush, Vice President Cheney, and other senior administration officials to whom Ashcroft had close personal ties were interviewed as part of that investigation. The risk of perceived partiality or partisan influence was too great.

Attorney General Alberto Gonzales's recusal in 2007 from an investigation into his Department's firing of nine U.S. Attorneys provides another example, as well as a warning. Investigations into the U.S. Attorneys' firings concluded that the Department acted in an inappropriately partisan manner. The temptation for partisan influence is not just perceived, it is real.

Officials must be most careful in cases when the stakes are greatest. With individuals of all political stripes alarmed by Russian interference into the 2016 elections, an attack on the foundation of our democratic system, a thorough and impartial probe is critical.

Following Sessions' recusal, authority to supervise the Russia probe fell to his deputy, Rod Rosenstein. Recognizing that the public interest required an investigation untainted by political ties to the White House, Rosenstein appointed former FBI director Robert Mueller as special counsel to investigate the matter. The move -- which like Sessions' recusal garnered bipartisan support -- provided the credibility demanded by the severity of the threat and by the rule of law.

Trump needs to get past the impulse to find an attorney general who will protect him rather than the public interest. Believe it or not, Mr. President, this moment is bigger than you.