In the 1930s, Prohibition era gangsters including Al Capone, "Machine Gun" Kelly, "Pretty Boy" Floyd, and John Dillinger were terrorizing the nation with machine-gun shootouts--with police and each other. Their weapon of choice was the Thompson machine gun, which created a lot of mayhem in a short period of time, firing .45-caliber cartridges at a rate of about eight rounds a second. Both the Valentine's Day Massacre of 1929 and the Kansas City Massacre of 1933 involved these guns.

In reaction, Congress passed the National Firearms Act of 1934, effectively ending machine gun sales in the United States.

Originally, the law was written at the behest of then-Attorney General Homer Cummings, who compared machine guns to weapons used by the Army. During Congressional testimony he said, "a machine gun, of course, ought never be in the hands of any private individual. There is not the slightest excuse for it." The final bill defined "machine gun" as "any weapon which shoots, or is designed to shoot, automatically or semi-automatically, more than one shot, without manual reloading, by a single function of the trigger." Later the law was amended to include hand grenades, poison gas, and other "destructive devices."

The National Firearms Act sought to limit the amount of mayhem one gun or device could cause. At the time of its passage, the then-president of the National Rifle Association said "very little of practical value can be accomplished by federal legislation on the point," but the law has been a good example of gun control working: In the eighty-three years since the law was passed, less than half of 1% of gun crimes have occurred by machine guns, as defined under the National Firearms Act.

Fast forward to 1994. To get around the intent of the Act, gun manufacturers made weapons that could fire larger, faster, and increasingly deadlier bullets at speeds as high as five rounds a second. Congress recognized the problem and passed the Assault Weapons Ban, which despite numerous loopholes did prevent the selling of AR-15s and other machine-gun-like weapons.

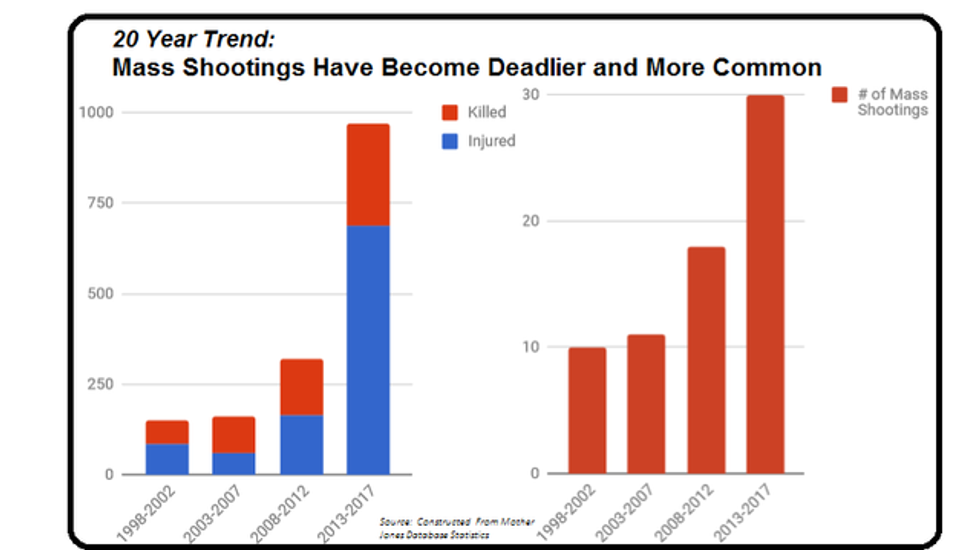

The ban expired in 2004, causing a huge boom of assault rifle sales. Since then, we've also seen a marked increase in mass shootings.

In fact, eighteen of the thirty most deadly attacks in modern U.S. history, including the worst five, have taken place during the last ten years. We've had two within a span of about a month: The Las Vegas shootings that killed fifty-eight and the Texas church shooting that killed twenty-six.

If we look at the twenty-year trend, it's clear that mass shootings have become more common, causing a higher death and injury toll:

Of the top five deadliest attacks, four were done with an AR-15 or similar semi-automatic assault rifles. (The one that didn't--the Virginia Tech massacre--used deadly hollow point bullets and a semi-automatic pistol that can fire several shots a second).

The effects of mass shootings on the public are indistinguishable from terrorist events in their ability to create fear. Yet there is a clear division in the response to these events.

When the shooter is someone with ties to ISIS or Islam, there are immediate calls to restrict non-whites and non-Christians from immigrating to the United States. When they are not, politicians tend to chalk the shootings up as a "mental health problem" or "pure evil." In the aftermath of the Texas shooting, Trump was quick to pronounce it, "Not a guns situation."

Except, it is a guns situation. If the nation was being terrorized by spear attacks, it would be a spears situation. If the nation was being terrorized by poison darts? A poison dart situation. Pianos being pushed off tall buildings? A pianos situation.

But, we don't have a pianos situation. We have a guns situation. Assault rifles and machine-gun-like weapons, to be exact.

It's as self-evident today as it was in the 1930s that letting private citizens possess weapons of mass destruction is a mammoth public policy problem affecting not only the victims, but an entire nation of people terrified that they might be next.

Keep reading...Show less