Millions of households would face tax increases or get little from the Senate tax bill - even before most of its individual income tax provisions would sunset in 2025, new Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) estimates released yesterday show. Nevertheless, in expressing his support for the bill today, Senator John McCain claimed that the Senate bill "would directly benefit all Americans." The JCT figures show that's not the case.

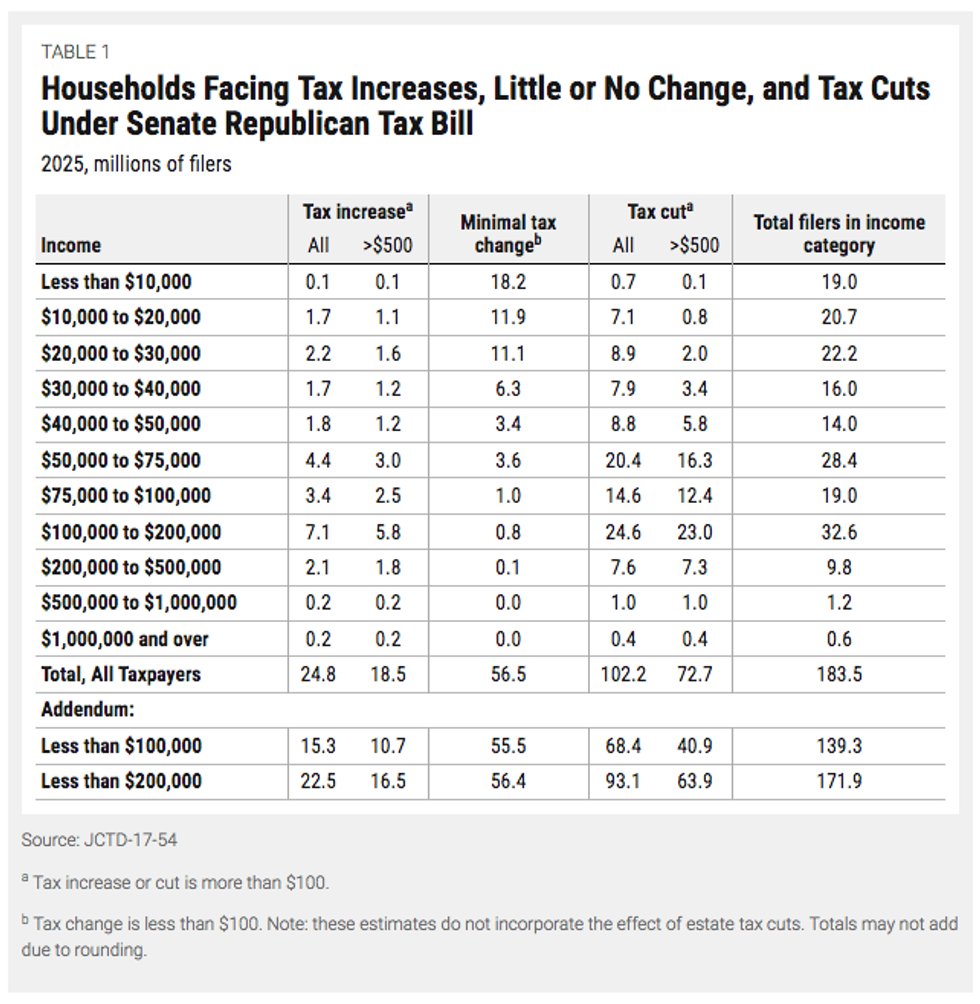

In 2025, when all the bill's individual income tax provisions are in place, about 79 million households with incomes below $200,000 -- or roughly 46 percent of households with incomes below $200,000 -- would either lose or gain little from the Senate bill (see Table 1):

- 22.5 million households with incomes below $200,000 would face tax increases, including 16.5 million facing tax increases of more than $500 apiece.

- 56.4 million households with incomes below $200,000 would face tax changes (increases or cuts) of less than $100 apiece.

Meanwhile, more than 70 percent of millionaire households would get a tax cut.

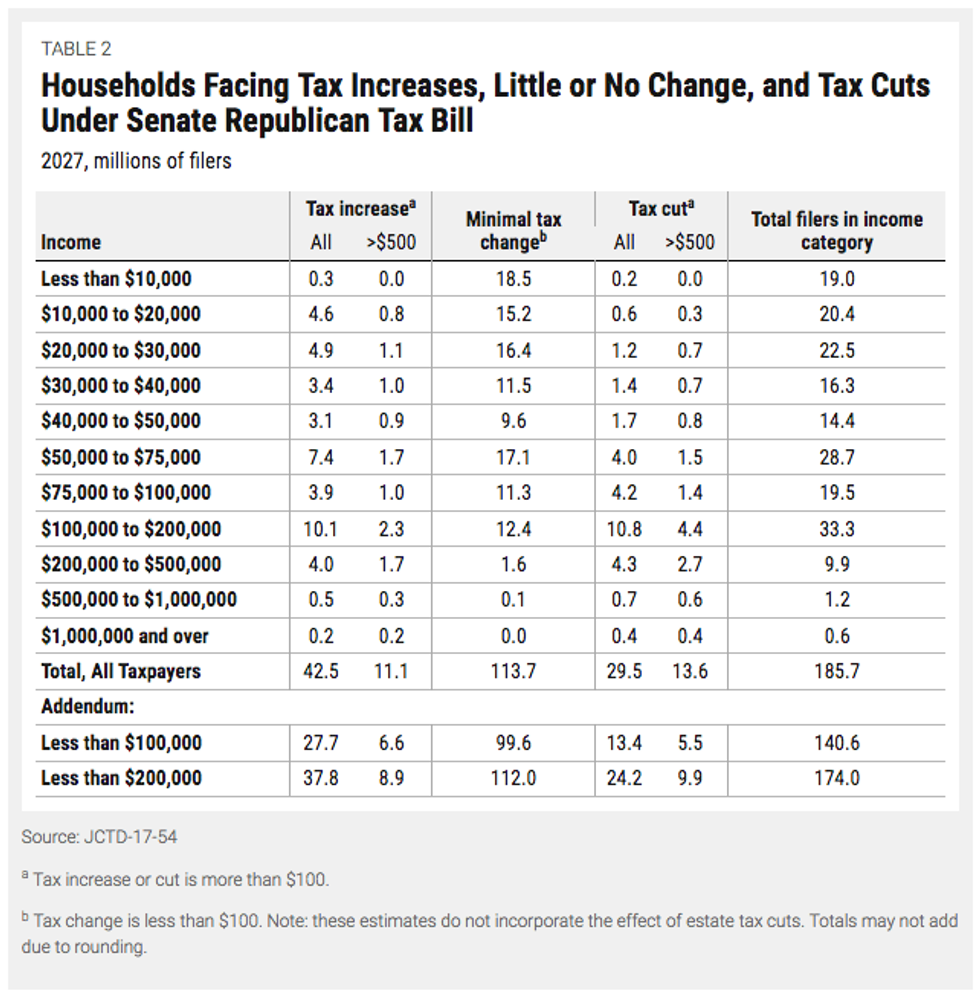

In 2027, the picture gets even worse because at the end of 2025, almost all of the bill's individual income tax provisions - including all of its individual income tax cuts - would expire. About 149.8 million households with incomes below $200,000 -- or roughly 70 percent of households with incomes below $200,000 -- would either lose or gain little from the Senate bill (see Table 2).

- 37.8 million households with incomes below $200,000 would face tax increases, including 8.9 million facing tax increases of more than $500 apiece.

- 112.0 million households with incomes below $200,000 would face tax changes of less than $100 apiece.

But more than 56 percent of millionaire households would continue to get a tax cut.

While many low- and middle-income households would be left even worse off at the end of 2025, the Senate GOP bill's deep corporate rate cuts would stay in place, permanently. To pay for those corporate rate cuts, the bill keeps in place its slower measure of inflation for adjusting tax brackets and other tax provisions each year, which raises taxes across the board (by, for instance, gradually pushing middle-income filers into higher tax brackets).

Also to pay for the corporate tax cuts, the bill keeps in place its repeal of the Affordable Care Act's individual mandate, the requirement that most people get health insurance or pay a penalty. All of the savings from repeal ($53 billion in 2027, for example) would come because fewer people would be insured, which would lower federal costs for Medicaid and for tax credits that help people buy insurance. The JCT estimates include the revenue savings (mainly from lower tax credits), but not the savings from lower Medicaid coverage or other spending effects.

Even these figures, though, don't show the full picture for most Americans. As we've explained, when policymakers eventually offset the costs of these deficit-financed tax cuts, the same low- and middle-income families that see little benefit from this bill upfront will likely bear much of the burden in the form of budget cuts. That is, these families would likely lose more in health care, education, job training, and other services than they'd gain in tax cuts, while high-income households would likely remain large net winners.