"I'd like to think of myself as ordinary," says Ross Grooters as he describes his life in Pleasant Hill, Iowa, an eastern suburb of Des Moines. But then he corrects himself. "Most people's passions or enjoyment are not going out and doing activist things, so that's where I'm not an ordinary Joe."

Indeed, it has been a long, strange trip for Grooters. After growing up as an "Air Force brat" in a conservative California family in the 1980s, this November, Grooters was elected to the Pleasant Hill City Council as a card-carrying member of the Democratic Socialists of America, having run on an openly left-wing platform.

Grooters' victory this year came in a town that in 2016 voted for Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton by a five-point margin, showing that even in a Republican-leaning area, socialists can win elections.

Grooters, whose day job is a locomotive engineer for Union Pacific Railroad, is active in Iowa Citizens for Community Improvement, a People's Action member organization (the present author is a member of People's Action communication staff). The Iowa CCI Action Fund endorsed Grooters, and trumpets his win as a major victory for the organization.

"Ross was one of the first movement candidates that we recruited and trained, and that our new Iowa CCI PAC endorsed and worked to get elected," read a post-election statement from Iowa CCA Action. His success, the organization said, was "powered by volunteers knocking over 4,000 doors and having over 1,500 conversations--not by buying ads and courting big-money donors."

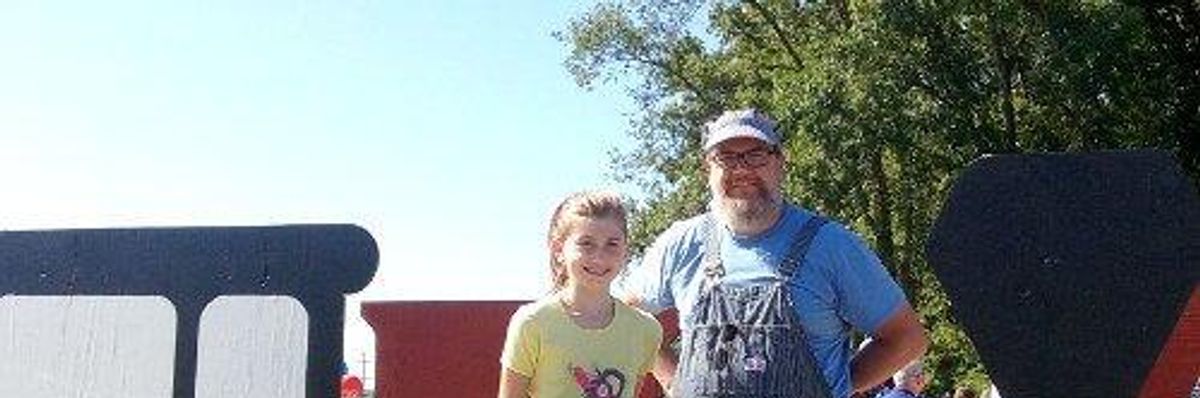

Grooters moved to Pleasant Hill 12 years ago, where he now lives with his wife and daughter, and joined Iowa CCI a few years later. "I realized politically minding my own business and having political apathy was not going to make my life better," he says.

His city council campaign reflected many of the issues that he says animate him personally: the struggles working-class families like his own face with stagnant wages and rising health care costs, the anti-immigrant fervor dividing his community and a clean water battle that is pitting Iowa families against powerful corporate agricultural interests.

Grooters ran on a pledge to fight for a higher minimum wage in the face of a state ordinance that prohibits counties and municipalities from raising their minimum wage above Iowa's state-wide minimum of $7.25 an hour. He also promised to battle corporate agribusinesses as they try to weaken regulations designed to stem the seepage of fertilizer and animal waste into streams and groundwater, as well as to sponsor a resolution designating Pleasant Hill a "welcoming community." During the campaign, he spoke out against the Trump administration's attempts to compel local law enforcement to help round up and deport undocumented immigrants.

Grooters is careful to steer people away from the idea that just because he won a local election in Trump country, he has mastered the art of getting Trump voters to elect an unabashed socialist. The turnout in the November 2017 election, he notes, was a fraction of the turnout in the presidential election a year earlier. Nonetheless, he believes his success offers lessons for other progressive and left candidates who find themselves in seemingly unfriendly political terrain.

"Whether you are on the left or the right of the political spectrum, everybody is facing the same economic hardships," Grooters says. He calls it "the specter of 'what happens if''"--the fear of being one paycheck away from financial disaster because of a medical emergency, a layoff or some other sudden expense. To address these fears, Grooters says his campaign focused on talking to voters about what has to change so that they can thrive rather than being left out of a prosperity being enjoyed by only a small group of the wealthy and well-connected.

While Grooters believes in connecting the struggles of white working-class people to the plight of communities of color and other marginalized groups, "when our message is around identity politics, it is not a winning message." What works better, he explains, is connecting with voters around shared values and needs.

"If we're means-testing what we're selling to voters, we're already excluding a lot of people who should be voting for us," Grooters says. "The best social programs we have are ones that are universal," he explains, as opposed to programs like the Affordable Care Act, which, though it helped many people gain healthcare coverage, was structured in a way that kept millions of others from benefiting. "If we talk to people on issues in a universal way, we are going to get their vote," he says.

Grooter's bottom-line advice for progressive and left candidates running on a bold people-centered platform in traditionally Republican districts? "I would say don't be afraid to run as what you are and what you believe in. Find a way to connect those issues to what everybody in the community is feeling, and I think you will do just fine."