On the afternoon of Dec. 31, 1870, the French writer Edmond de Goncourt went to a butcher shop in Paris and saw, for sale, the trunk of Pollux, the young elephant from the zoo.

The city was under siege. The French government had blundered into a war with Prussia and been disastrously defeated; Paris was surrounded by the enemy and no food could get in.

In that New Year's Eve passage, Goncourt is recording his own shock. He understands there isn't much meat to be had, but now it's gotten to the point where even animals associated with familiar bourgeois pleasures -- he knows the elephant's name, he knows that everyone knows the elephant's name -- are being slaughtered for food.

I came upon this passage recently in "On Christmas," a little collection of essays about the holiday season. Some were cheery, some dark; but this one jumped out because it was political. It wasn't directly about elections or leaders. It was about the impact of politics (in this case, an elected president turned self-declared emperor) on the lives of everyday citizens.

I read this piece sitting up in a warm bed after having eaten a good dinner. Yet the words chilled me in a way that they wouldn't have if I'd read them a year-and-a-half ago. As a white middle-class American born in the second half of the 20th century, I've had the unusual, and unearned, luxury of feeling like a spectator to history. My Russian grandparents fled pogroms; my German-Jewish father fled Hitler; my mother's French Jewish cousins died in the camps. I've known about these terrifying experiences while also having been insulated from them; I've known these stories as stories.

But 2017 has been a different kind of year. We have a leader who has gleefully and recklessly been dismantling and destabilizing our government and our ties with other governments around the world, and the majority party in Congress has been colluding. Some days it feels as if no one is driving the car and some days it feels as if a maniac is driving; one of these days, the car is going to crash into a tree or an oncoming vehicle. We're afraid of what's happening, and we don't know what will happen next.

I have always thought of Edmond de Goncourt as a historian, but actually he was a diarist. He was writing about the moment while still in the moment. When he went into that butcher shop on New Year's Eve, he was sickened and scared and he didn't know what was going to happen next. He didn't know that the Germans were about to start shelling Paris, or that the siege would be followed by a violent and bloody civil war among the French, or that subsequently he would get to live out the rest of his life during decades of relative peace and prosperity.

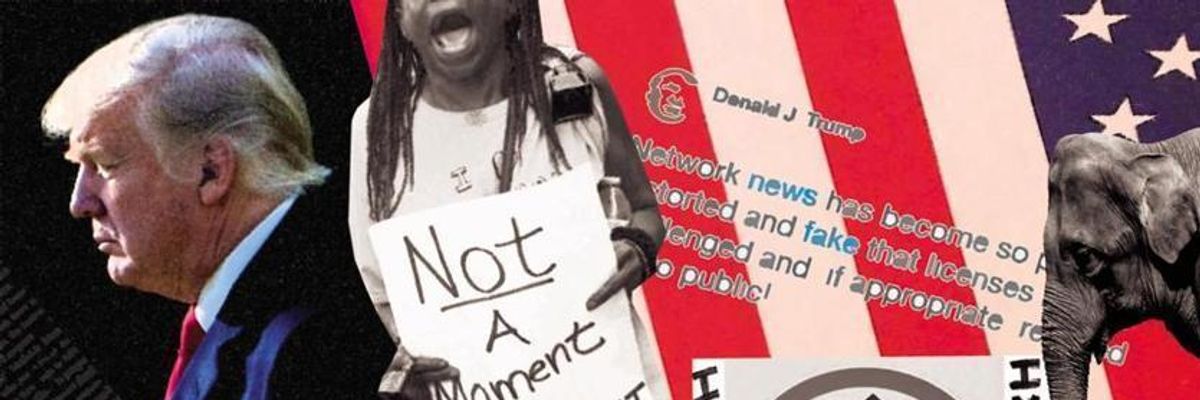

The other morning, going into a store, I held the door open for a woman who was in her 80s or even 90s. She was walking with a cane and wearing a hand-knitted pink hat. I know what her hat looked like to me in the moment (solidarity, protest, a continuation of last January's Women's March), but I'm also newly aware that we are living through a series of moments that will take shape as history -- stories told, analyzed, and understood -- only in hindsight. We don't know yet what all this will add up to. For now, what we have are fragments: the pink hats, the unhinged tweets, the white supremacists marching with torches in Charlottesville, the cries of "fake news." The trunk and the heart of Goncourt's Pollux the elephant, hanging in a Paris butcher shop.