Netflix CEO Reed Hastings promotes one of his service's big successes, the series "Daredevil," at a 2016 conference. (Robyn Beck / AFP/Getty Images)

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Netflix CEO Reed Hastings promotes one of his service's big successes, the series "Daredevil," at a 2016 conference. (Robyn Beck / AFP/Getty Images)

The big news Friday on the executive compensation front is that Netflix is converting some of its "performance-based" pay for its top executives to straight salaries, thanks to the recently-passed tax bill.

But people may be taking the wrong lesson from the change. On the surface, it looks like the five executives covered by the change are getting big raises thanks to the tax bill. But the reality is a bit more complicated. And what the new policy at Netflix really tells us is that the old "performance-based" executive compensation system always was a sham, anyway.

Here's the backstory.

For nearly a quarter-century, or since the Clinton era, tax deductions for executive salaries have been limited to $1 million per executive. But there's a loophole. The excess is deductible by the company as long as it's "performance-based" -- in other words, if it's subject to targets set by the corporate board, such as stock price appreciation, profitability, dealmaking and so on.

The Republican tax bill signed by President Trump on Dec. 22 eliminated the loophole. Henceforth, none of that pay will be deductible, performance-based or not. That might sound like a hit on corporate CEOs uncharacteristic of the GOP, but keep in mind that the tax bill also cut the top corporate tax rate to 21% from 35%. That reduced the value of the tax deduction anyway.

Closing the loophole will bring in $9.3 billion over 10 years, according to the Congressional Joint Committee on Taxation -- a pittance, compared to the $1.4-trillion cost of the tax cuts handed over mostly to corporations and the wealthy. Taxpayers in the CEO strata typically make so much money that they'll be collecting immense tax breaks as a result of the bill.

The limit on tax deductions was designed in 1993 to put a leash on rapidly-rising executive compensation. Bill Clinton's 1992 campaign platform, after all, had taken aim at corporate tax deductions that "reward outrageous executive pay."

But the scheme never worked. If anything, by encouraging corporations to tie executive pay closely to stock gains, it led to an explosion in compensation. Average CEO pay at the top 350 U.S. companies (ranked by sales) was an inflation-adjusted $843,000 in 1965, about $6 million in 1995, and $15.7 million in 2015, according to the labor-oriented Economic Policy Institute. Executive pay closely tracked the stock market, as CEOs met their performance goals by steering more corporate resources into propping up their share prices.

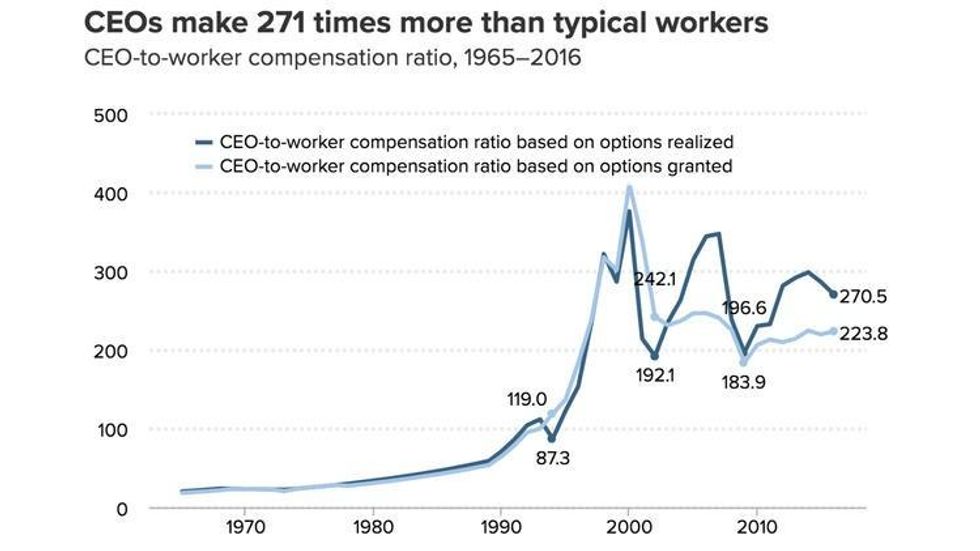

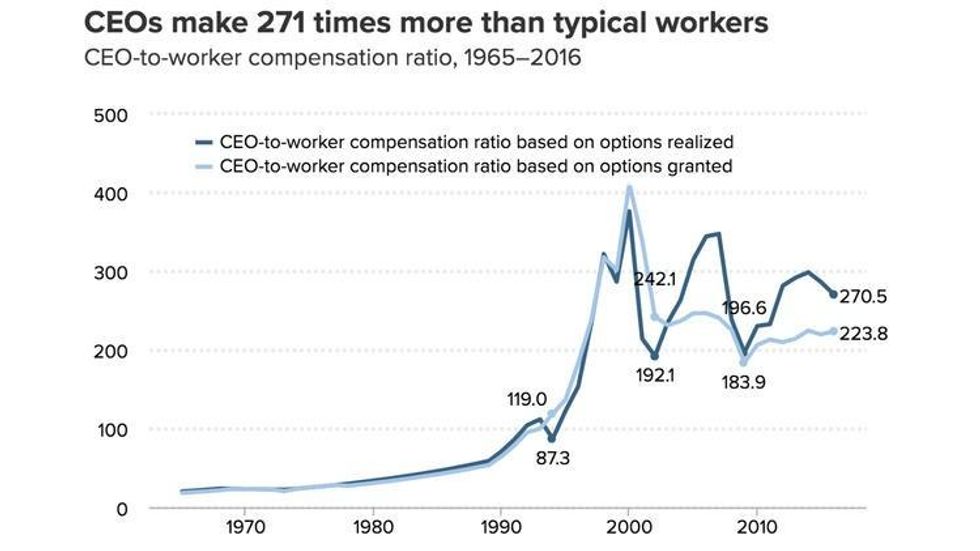

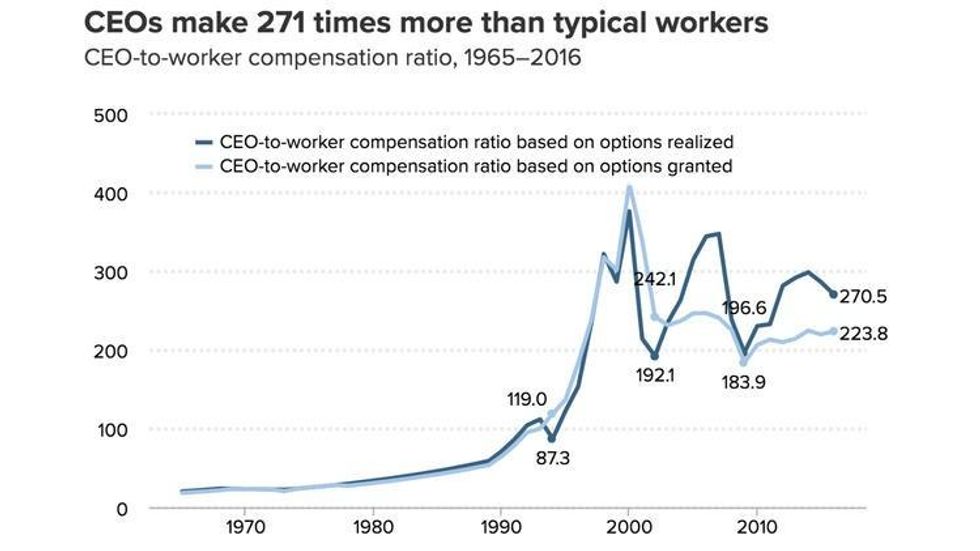

What really took off was CEO pay in relation to average worker pay. CEOs made about 20 times the typical worker in 1965, but 270.5 times worker pay in 2016. The CEO-to-worker ratios hit peaks during stock market highs in 2000 (when it was 411.3 times worker pay) and 2007 (when the figure was 347.5). Meanwhile, worker pay stagnated.

"Exorbitant CEO pay means that the fruits of economic growth are not going to ordinary workers," the Economic Policy Institute observed. The think tank recommended that executive pay be reined in by, among other things, raising the marginal tax rates for the richest taxpayers, setting corporate tax rates higher for companies with the highest ratios of CEO-to-worker pay, and eliminating the tax break for performance pay. The GOP tax bill may have implemented the third recommendation, but it took the opposite tack on the first two.

Companies have become adept at tailoring performance targets to guarantee maximum pay for top executives. The definition of "performance" became suspiciously flexible, as if corporate boards first decided how much to pay their executives, and then cobbled together performance targets to make sure they hit the mark. A great example was the pay of IBM's chief executive, Virginia Rometty.

As we reported, in 2016, the fifth year of her tenure, IBM's revenue declined 2% to $79.9 billion; the company turned in four more quarters of shrinking revenue, making 19 in a row; and its full-year profit was down 11% to $11.9 billion. Based on this "performance," Rometty's bonus rose to $4.95 million from $4.5 million -- her largest bonus ever.

That brings us back to Netflix. The company's new compensation structure covers Chairman and Chief Executive Reed Hastings, Chief Financial Officer David Wells, Chief Content Officer Ted Sarandos, Chief Product Officer Greg Peters and General Counsel David Hyman.

Until now, their pay chiefly comprised a cash salary and a performance-based bonus. Henceforth, the company announced, their bonus will be folded into their cash salary and no longer tied to performance goals.

Was that ever the case, however? In 2016, the three executives subject to the performance bonus all hit their bonus targets exactly, collecting 100% of the $10.75 million combined that they were due. (The chief product officer then was Neil Hunt, not Peters, and CFO Wells wasn't subject to the performance rules.) In 2015, Hunt, Peters and Sarandos were docked just a hair on their third-quarter bonuses for reasons that aren't set forth in company disclosures. Hunt lost $2,500 of his $5-million bonus, or five hundredths of one percent; Sarandos lost $5,000 of his $2-million bonus and Peters $2,500 of his $1 million -- a quarter of a percent in both cases.

For 2018, according to Friday's announcement, the top executives all appear to be in line for healthy raises of 20% or more, mostly from stock option grants. Wells will receive a total of $5.25 million, Peters $12.6 million and Sarandos $26.2 million. Hastings, who hasn't been part of the bonus pool, but has been paid almost entirely through stock options, is to receive options valued at $28.7 million, up from $21.2 million this year. On the downside, his cash salary will be cut to $700,000 from $850,000.

That's not to say that Netflix hasn't turned in a sterling year. For the first three quarters of 2017, revenue gained more than 30% and profits more than tripled; the shares have advanced by about 55%.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

The big news Friday on the executive compensation front is that Netflix is converting some of its "performance-based" pay for its top executives to straight salaries, thanks to the recently-passed tax bill.

But people may be taking the wrong lesson from the change. On the surface, it looks like the five executives covered by the change are getting big raises thanks to the tax bill. But the reality is a bit more complicated. And what the new policy at Netflix really tells us is that the old "performance-based" executive compensation system always was a sham, anyway.

Here's the backstory.

For nearly a quarter-century, or since the Clinton era, tax deductions for executive salaries have been limited to $1 million per executive. But there's a loophole. The excess is deductible by the company as long as it's "performance-based" -- in other words, if it's subject to targets set by the corporate board, such as stock price appreciation, profitability, dealmaking and so on.

The Republican tax bill signed by President Trump on Dec. 22 eliminated the loophole. Henceforth, none of that pay will be deductible, performance-based or not. That might sound like a hit on corporate CEOs uncharacteristic of the GOP, but keep in mind that the tax bill also cut the top corporate tax rate to 21% from 35%. That reduced the value of the tax deduction anyway.

Closing the loophole will bring in $9.3 billion over 10 years, according to the Congressional Joint Committee on Taxation -- a pittance, compared to the $1.4-trillion cost of the tax cuts handed over mostly to corporations and the wealthy. Taxpayers in the CEO strata typically make so much money that they'll be collecting immense tax breaks as a result of the bill.

The limit on tax deductions was designed in 1993 to put a leash on rapidly-rising executive compensation. Bill Clinton's 1992 campaign platform, after all, had taken aim at corporate tax deductions that "reward outrageous executive pay."

But the scheme never worked. If anything, by encouraging corporations to tie executive pay closely to stock gains, it led to an explosion in compensation. Average CEO pay at the top 350 U.S. companies (ranked by sales) was an inflation-adjusted $843,000 in 1965, about $6 million in 1995, and $15.7 million in 2015, according to the labor-oriented Economic Policy Institute. Executive pay closely tracked the stock market, as CEOs met their performance goals by steering more corporate resources into propping up their share prices.

What really took off was CEO pay in relation to average worker pay. CEOs made about 20 times the typical worker in 1965, but 270.5 times worker pay in 2016. The CEO-to-worker ratios hit peaks during stock market highs in 2000 (when it was 411.3 times worker pay) and 2007 (when the figure was 347.5). Meanwhile, worker pay stagnated.

"Exorbitant CEO pay means that the fruits of economic growth are not going to ordinary workers," the Economic Policy Institute observed. The think tank recommended that executive pay be reined in by, among other things, raising the marginal tax rates for the richest taxpayers, setting corporate tax rates higher for companies with the highest ratios of CEO-to-worker pay, and eliminating the tax break for performance pay. The GOP tax bill may have implemented the third recommendation, but it took the opposite tack on the first two.

Companies have become adept at tailoring performance targets to guarantee maximum pay for top executives. The definition of "performance" became suspiciously flexible, as if corporate boards first decided how much to pay their executives, and then cobbled together performance targets to make sure they hit the mark. A great example was the pay of IBM's chief executive, Virginia Rometty.

As we reported, in 2016, the fifth year of her tenure, IBM's revenue declined 2% to $79.9 billion; the company turned in four more quarters of shrinking revenue, making 19 in a row; and its full-year profit was down 11% to $11.9 billion. Based on this "performance," Rometty's bonus rose to $4.95 million from $4.5 million -- her largest bonus ever.

That brings us back to Netflix. The company's new compensation structure covers Chairman and Chief Executive Reed Hastings, Chief Financial Officer David Wells, Chief Content Officer Ted Sarandos, Chief Product Officer Greg Peters and General Counsel David Hyman.

Until now, their pay chiefly comprised a cash salary and a performance-based bonus. Henceforth, the company announced, their bonus will be folded into their cash salary and no longer tied to performance goals.

Was that ever the case, however? In 2016, the three executives subject to the performance bonus all hit their bonus targets exactly, collecting 100% of the $10.75 million combined that they were due. (The chief product officer then was Neil Hunt, not Peters, and CFO Wells wasn't subject to the performance rules.) In 2015, Hunt, Peters and Sarandos were docked just a hair on their third-quarter bonuses for reasons that aren't set forth in company disclosures. Hunt lost $2,500 of his $5-million bonus, or five hundredths of one percent; Sarandos lost $5,000 of his $2-million bonus and Peters $2,500 of his $1 million -- a quarter of a percent in both cases.

For 2018, according to Friday's announcement, the top executives all appear to be in line for healthy raises of 20% or more, mostly from stock option grants. Wells will receive a total of $5.25 million, Peters $12.6 million and Sarandos $26.2 million. Hastings, who hasn't been part of the bonus pool, but has been paid almost entirely through stock options, is to receive options valued at $28.7 million, up from $21.2 million this year. On the downside, his cash salary will be cut to $700,000 from $850,000.

That's not to say that Netflix hasn't turned in a sterling year. For the first three quarters of 2017, revenue gained more than 30% and profits more than tripled; the shares have advanced by about 55%.

The big news Friday on the executive compensation front is that Netflix is converting some of its "performance-based" pay for its top executives to straight salaries, thanks to the recently-passed tax bill.

But people may be taking the wrong lesson from the change. On the surface, it looks like the five executives covered by the change are getting big raises thanks to the tax bill. But the reality is a bit more complicated. And what the new policy at Netflix really tells us is that the old "performance-based" executive compensation system always was a sham, anyway.

Here's the backstory.

For nearly a quarter-century, or since the Clinton era, tax deductions for executive salaries have been limited to $1 million per executive. But there's a loophole. The excess is deductible by the company as long as it's "performance-based" -- in other words, if it's subject to targets set by the corporate board, such as stock price appreciation, profitability, dealmaking and so on.

The Republican tax bill signed by President Trump on Dec. 22 eliminated the loophole. Henceforth, none of that pay will be deductible, performance-based or not. That might sound like a hit on corporate CEOs uncharacteristic of the GOP, but keep in mind that the tax bill also cut the top corporate tax rate to 21% from 35%. That reduced the value of the tax deduction anyway.

Closing the loophole will bring in $9.3 billion over 10 years, according to the Congressional Joint Committee on Taxation -- a pittance, compared to the $1.4-trillion cost of the tax cuts handed over mostly to corporations and the wealthy. Taxpayers in the CEO strata typically make so much money that they'll be collecting immense tax breaks as a result of the bill.

The limit on tax deductions was designed in 1993 to put a leash on rapidly-rising executive compensation. Bill Clinton's 1992 campaign platform, after all, had taken aim at corporate tax deductions that "reward outrageous executive pay."

But the scheme never worked. If anything, by encouraging corporations to tie executive pay closely to stock gains, it led to an explosion in compensation. Average CEO pay at the top 350 U.S. companies (ranked by sales) was an inflation-adjusted $843,000 in 1965, about $6 million in 1995, and $15.7 million in 2015, according to the labor-oriented Economic Policy Institute. Executive pay closely tracked the stock market, as CEOs met their performance goals by steering more corporate resources into propping up their share prices.

What really took off was CEO pay in relation to average worker pay. CEOs made about 20 times the typical worker in 1965, but 270.5 times worker pay in 2016. The CEO-to-worker ratios hit peaks during stock market highs in 2000 (when it was 411.3 times worker pay) and 2007 (when the figure was 347.5). Meanwhile, worker pay stagnated.

"Exorbitant CEO pay means that the fruits of economic growth are not going to ordinary workers," the Economic Policy Institute observed. The think tank recommended that executive pay be reined in by, among other things, raising the marginal tax rates for the richest taxpayers, setting corporate tax rates higher for companies with the highest ratios of CEO-to-worker pay, and eliminating the tax break for performance pay. The GOP tax bill may have implemented the third recommendation, but it took the opposite tack on the first two.

Companies have become adept at tailoring performance targets to guarantee maximum pay for top executives. The definition of "performance" became suspiciously flexible, as if corporate boards first decided how much to pay their executives, and then cobbled together performance targets to make sure they hit the mark. A great example was the pay of IBM's chief executive, Virginia Rometty.

As we reported, in 2016, the fifth year of her tenure, IBM's revenue declined 2% to $79.9 billion; the company turned in four more quarters of shrinking revenue, making 19 in a row; and its full-year profit was down 11% to $11.9 billion. Based on this "performance," Rometty's bonus rose to $4.95 million from $4.5 million -- her largest bonus ever.

That brings us back to Netflix. The company's new compensation structure covers Chairman and Chief Executive Reed Hastings, Chief Financial Officer David Wells, Chief Content Officer Ted Sarandos, Chief Product Officer Greg Peters and General Counsel David Hyman.

Until now, their pay chiefly comprised a cash salary and a performance-based bonus. Henceforth, the company announced, their bonus will be folded into their cash salary and no longer tied to performance goals.

Was that ever the case, however? In 2016, the three executives subject to the performance bonus all hit their bonus targets exactly, collecting 100% of the $10.75 million combined that they were due. (The chief product officer then was Neil Hunt, not Peters, and CFO Wells wasn't subject to the performance rules.) In 2015, Hunt, Peters and Sarandos were docked just a hair on their third-quarter bonuses for reasons that aren't set forth in company disclosures. Hunt lost $2,500 of his $5-million bonus, or five hundredths of one percent; Sarandos lost $5,000 of his $2-million bonus and Peters $2,500 of his $1 million -- a quarter of a percent in both cases.

For 2018, according to Friday's announcement, the top executives all appear to be in line for healthy raises of 20% or more, mostly from stock option grants. Wells will receive a total of $5.25 million, Peters $12.6 million and Sarandos $26.2 million. Hastings, who hasn't been part of the bonus pool, but has been paid almost entirely through stock options, is to receive options valued at $28.7 million, up from $21.2 million this year. On the downside, his cash salary will be cut to $700,000 from $850,000.

That's not to say that Netflix hasn't turned in a sterling year. For the first three quarters of 2017, revenue gained more than 30% and profits more than tripled; the shares have advanced by about 55%.