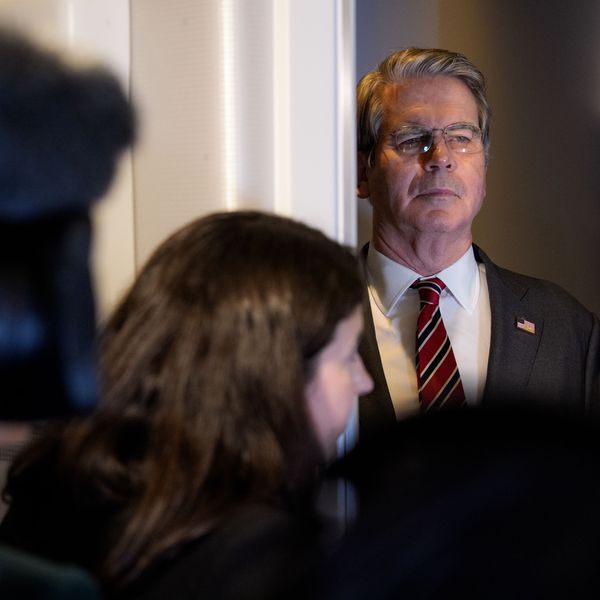

"Since the law's enactment corporations are buying back their own stock and issuing dividends to shareholders far more than they are investing." (Photo: Screenshot/youtube)

Hassett Changes Story on "Repatriated" Foreign Profits Under New Tax Law

Repatriated cash overwhelmingly ends up in shareholders’ pockets, not in investments in factories and the like.

With new reports that companies are using their windfall from the new tax law in ways that mostly benefit wealthy investors rather than workers, Council of Economic Advisers Chair Kevin Hassett has revised his explanation of how companies will use foreign earnings they "repatriate" to this country under the new law.

The core of the law is large, permanent corporate tax cuts, including on multinationals' foreign profits. In transitioning to this more generous system, the law subjects the roughly $2.6 trillion in profits that U.S. multinationals held overseas to a compulsory, one-time tax at rates well below the new 21 percent rate on domestic profits. After paying this "deemed repatriation tax," multinationals will have a huge sum of money to reallocate.

Before the law's enactment, Hassett argued that its combination of deemed repatriation and a deep cut in the corporate rate (which was 35 percent before the new law took effect) would prompt firms to invest repatriated money in the United States -- such as by building factories, which in turn would increase jobs and raise wages:

So now in this bill we become an attractive place, and so with the one time repatriation fee, that's going to free up a lot of money to come back and build factories here and so on.

Instead, since the law's enactment corporations are buying back their own stock and issuing dividends to shareholders far more than they are investing. Indeed, U.S. companies have announced a record amount of planned share buybacks this quarter -- more than $178 billion -- according to the market research firm Birinyi Associates.

Responding to these developments, Hassett last week gave a different explanation about the impact of repatriation:

QUESTION: . . . [A] Morgan Stanley survey of stock analysts who are looking at how companies are spending their tax savings . . . said about 13 percent was going to workers, 17 percent to capital spending, and 43 percent to dividends and buybacks, that is shareholders. Your model was that a much higher percentage was ultimately going to wind up in the pocketbook.

HASSETT: Sure. And it will. Yeah.

QUESTION: So what are the stock analysts missing there?

HASSETT: Well, the thing that you have to remember is that we're starting out with trillions of dollars that were parked overseas. And that trillions of dollars -- those monies are coming home right now and that's a one-time adjustment. And a lot of firms are taking that money and they're paying bonuses, but they're also doing things like increasing dividends and doing share buybacks, which sometimes happens when firms find money. . . .

That's consistent with past experience: repatriated cash overwhelmingly ends up in shareholders' pockets, not in investments in factories and the like. We warned last year that corporations would likely distribute repatriated cash to shareholders through stock buybacks and dividends. That's what corporations did with cash freed up by a repatriation tax "holiday" in 2004, which offered multinationals a one-time, sharply reduced tax rate on repatriated profits. And in recent years, many of the technology and drug companies with the largest offshore profits have already been using any free cash to make record payouts to shareholders.

It's good that Hassett has acknowledged that repatriated profits are going overwhelmingly to stock buybacks and dividend increases, as they have in the past. But it's a shame that he ignored the record when he was pushing for Congress to pass the new tax law.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

With new reports that companies are using their windfall from the new tax law in ways that mostly benefit wealthy investors rather than workers, Council of Economic Advisers Chair Kevin Hassett has revised his explanation of how companies will use foreign earnings they "repatriate" to this country under the new law.

The core of the law is large, permanent corporate tax cuts, including on multinationals' foreign profits. In transitioning to this more generous system, the law subjects the roughly $2.6 trillion in profits that U.S. multinationals held overseas to a compulsory, one-time tax at rates well below the new 21 percent rate on domestic profits. After paying this "deemed repatriation tax," multinationals will have a huge sum of money to reallocate.

Before the law's enactment, Hassett argued that its combination of deemed repatriation and a deep cut in the corporate rate (which was 35 percent before the new law took effect) would prompt firms to invest repatriated money in the United States -- such as by building factories, which in turn would increase jobs and raise wages:

So now in this bill we become an attractive place, and so with the one time repatriation fee, that's going to free up a lot of money to come back and build factories here and so on.

Instead, since the law's enactment corporations are buying back their own stock and issuing dividends to shareholders far more than they are investing. Indeed, U.S. companies have announced a record amount of planned share buybacks this quarter -- more than $178 billion -- according to the market research firm Birinyi Associates.

Responding to these developments, Hassett last week gave a different explanation about the impact of repatriation:

QUESTION: . . . [A] Morgan Stanley survey of stock analysts who are looking at how companies are spending their tax savings . . . said about 13 percent was going to workers, 17 percent to capital spending, and 43 percent to dividends and buybacks, that is shareholders. Your model was that a much higher percentage was ultimately going to wind up in the pocketbook.

HASSETT: Sure. And it will. Yeah.

QUESTION: So what are the stock analysts missing there?

HASSETT: Well, the thing that you have to remember is that we're starting out with trillions of dollars that were parked overseas. And that trillions of dollars -- those monies are coming home right now and that's a one-time adjustment. And a lot of firms are taking that money and they're paying bonuses, but they're also doing things like increasing dividends and doing share buybacks, which sometimes happens when firms find money. . . .

That's consistent with past experience: repatriated cash overwhelmingly ends up in shareholders' pockets, not in investments in factories and the like. We warned last year that corporations would likely distribute repatriated cash to shareholders through stock buybacks and dividends. That's what corporations did with cash freed up by a repatriation tax "holiday" in 2004, which offered multinationals a one-time, sharply reduced tax rate on repatriated profits. And in recent years, many of the technology and drug companies with the largest offshore profits have already been using any free cash to make record payouts to shareholders.

It's good that Hassett has acknowledged that repatriated profits are going overwhelmingly to stock buybacks and dividend increases, as they have in the past. But it's a shame that he ignored the record when he was pushing for Congress to pass the new tax law.

With new reports that companies are using their windfall from the new tax law in ways that mostly benefit wealthy investors rather than workers, Council of Economic Advisers Chair Kevin Hassett has revised his explanation of how companies will use foreign earnings they "repatriate" to this country under the new law.

The core of the law is large, permanent corporate tax cuts, including on multinationals' foreign profits. In transitioning to this more generous system, the law subjects the roughly $2.6 trillion in profits that U.S. multinationals held overseas to a compulsory, one-time tax at rates well below the new 21 percent rate on domestic profits. After paying this "deemed repatriation tax," multinationals will have a huge sum of money to reallocate.

Before the law's enactment, Hassett argued that its combination of deemed repatriation and a deep cut in the corporate rate (which was 35 percent before the new law took effect) would prompt firms to invest repatriated money in the United States -- such as by building factories, which in turn would increase jobs and raise wages:

So now in this bill we become an attractive place, and so with the one time repatriation fee, that's going to free up a lot of money to come back and build factories here and so on.

Instead, since the law's enactment corporations are buying back their own stock and issuing dividends to shareholders far more than they are investing. Indeed, U.S. companies have announced a record amount of planned share buybacks this quarter -- more than $178 billion -- according to the market research firm Birinyi Associates.

Responding to these developments, Hassett last week gave a different explanation about the impact of repatriation:

QUESTION: . . . [A] Morgan Stanley survey of stock analysts who are looking at how companies are spending their tax savings . . . said about 13 percent was going to workers, 17 percent to capital spending, and 43 percent to dividends and buybacks, that is shareholders. Your model was that a much higher percentage was ultimately going to wind up in the pocketbook.

HASSETT: Sure. And it will. Yeah.

QUESTION: So what are the stock analysts missing there?

HASSETT: Well, the thing that you have to remember is that we're starting out with trillions of dollars that were parked overseas. And that trillions of dollars -- those monies are coming home right now and that's a one-time adjustment. And a lot of firms are taking that money and they're paying bonuses, but they're also doing things like increasing dividends and doing share buybacks, which sometimes happens when firms find money. . . .

That's consistent with past experience: repatriated cash overwhelmingly ends up in shareholders' pockets, not in investments in factories and the like. We warned last year that corporations would likely distribute repatriated cash to shareholders through stock buybacks and dividends. That's what corporations did with cash freed up by a repatriation tax "holiday" in 2004, which offered multinationals a one-time, sharply reduced tax rate on repatriated profits. And in recent years, many of the technology and drug companies with the largest offshore profits have already been using any free cash to make record payouts to shareholders.

It's good that Hassett has acknowledged that repatriated profits are going overwhelmingly to stock buybacks and dividend increases, as they have in the past. But it's a shame that he ignored the record when he was pushing for Congress to pass the new tax law.