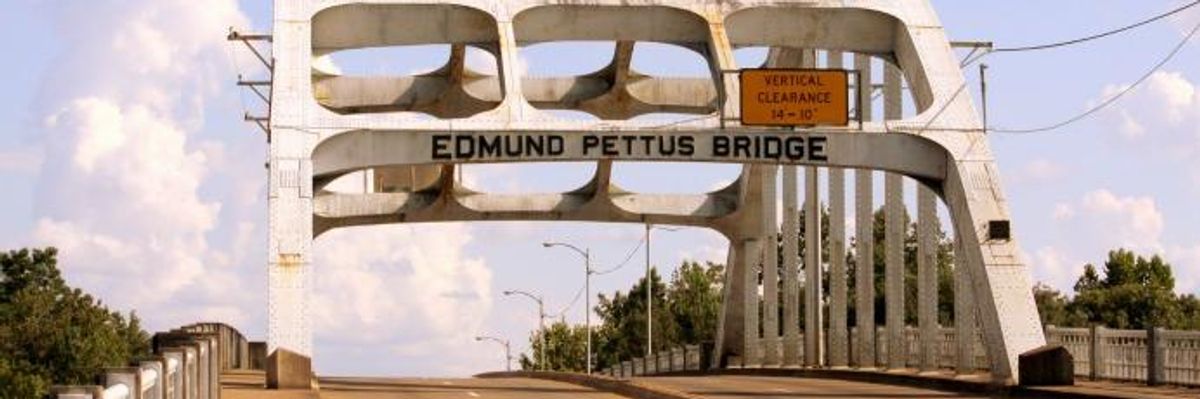

The Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama.

Marching Backwards for Freedom

The truth is, we need a powerful movement for voting rights, economic and racial justice, just as much today as we did fifty-three years ago.

In 1965, Martin Luther King, Jr. led marchers to the Dallas County Courthouse in Selma, Alabama to demand their right to vote. When they got there, they were arrested. That arrest, and the police brutality that followed it, galvanized the nation and forced passage of the Voting Rights Act.

Yet in 2018, many of us still do not have our right to vote. More than six million nationwide are disenfranchised because of state laws rooted in white supremacy. Millions more don't vote because someone lied and told us we can't, because we are or were in prison or have a conviction in our past.

So now we've come back to Selma to finish what King started: to recover and restore his movement.

Marching Backwards

I come to Selma every year on Bloody Sunday. That's the day in March when King's marchers were met by riot police on Edmund Pettis Bridge. Now, this anniversary is a jubilee: we cross the bridge to celebrate how far we've come, with marching bands, banners and choirs.

But there's more work to be done. So we start every year's jubilee with a "Backwards March": Holding hands, I join other pastors and the formerly incarcerated to march backwards across the bridge, at the head of the parade. No one crosses the bridge until we've finished. Then the celebration continues.

Why do we march backwards? To remind us of everyone who's been left behind. We've got to go back and get them, and get things right, so we can move forward.

We march under this banner: "From the back of the bus to the front of the prison, the struggle continues."

Restoring Rights

I am formerly incarcerated myself. When I was released, I took the state of Alabama to court to regain my vote, then to restore this right to others. Because of these efforts, a quarter of a million in Alabama now have their voting rights restored.

But many still don't know they can vote. So since 2003, with help from the Drug Policy Alliance and Project South, I've gone inside jails to register voters. Because even if you're on the inside in Alabama, if you're not yet convicted, or convicted of a misdemeanor or a nonviolent drug offense, you can vote. No matter what you've been told.

Every Step Of The Way

These millions of men and women - the incarcerated and formerly incarcerated - are America's truly forgotten. They're not on anybody's list, or in anybody's poll; they've never been counted. No one ever thought we'd overcome the odds and vote.

Alabama's GOP has fought me every step of the way. Why? Because the last thing they want is for these millions of voters to regain their rights. One of the officials who opposed me most, Mike Hubbard, is now in prison for fraud. He can vote now, too, thanks to our efforts. You can't make this up.

Abolishing Slavery

Slavery still exists in the United States. That's because the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which abolished slavery in 1865, says it can still exist "as a punishment for crime." Prisoners all across this country are forced to work for free, or for pennies on the dollar.

But that's not all the Constitution says. The Eighth Amendment also bans "cruel and unusual punishment." What punishment is more more cruel and unusual than this modern form of slavery?

And in states all across the South, intentionally vague "Moral Turpitude" clauses bar those convicted of crimes from the vote. So in 2008, I sued Alabama and forced the state to allow me to extend voting rights to prisoners. In 2017, Alabama finally passed a law to clearly define crimes of "moral turpitude" which has re-enfranchised most of the 286,000 people with felony convictions in the state. But many of them still don't know they can vote. And hundreds of thousands more across the South - in Florida alone, there are 1.3 million - are waiting for this right to be restored.

So yes, there's work to be done.

Non-Violence Is Not Non-Movement

Now, we've launched #Free2Vote, a multi-state initiative with the People's Action Mass Liberation Campaign, Project South & the Southern Movement Assembly to register voters inside and outside of prisons and jails.

The only thing that declares your full citizenship is the right to vote. So we'll continue in Alabama, then move on to Florida, Georgia and other states of the South and North where voters have been disenfranchised through mass incarceration. A hundred million Americans are impacted by criminal convictions.

This is an insight I learned in Selma. Non-violence, one of our great lessons from Dr. King, has been misinterpreted by some to mean "non-movement." But the truth is, we need a powerful movement for voting rights, economic and racial justice, just as much today as we did fifty-three years ago.

So it's time to fulfill Dr. King's dream - to restore and revive his movement. We must go back, get what was lost, and move forward to restore the right to vote to America's truly forgotten men and women: the incarcerated, formerly incarcerated, those with criminal convictions as well as those sitting in jail who aren't convicted of anything, just waiting for trial.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

In 1965, Martin Luther King, Jr. led marchers to the Dallas County Courthouse in Selma, Alabama to demand their right to vote. When they got there, they were arrested. That arrest, and the police brutality that followed it, galvanized the nation and forced passage of the Voting Rights Act.

Yet in 2018, many of us still do not have our right to vote. More than six million nationwide are disenfranchised because of state laws rooted in white supremacy. Millions more don't vote because someone lied and told us we can't, because we are or were in prison or have a conviction in our past.

So now we've come back to Selma to finish what King started: to recover and restore his movement.

Marching Backwards

I come to Selma every year on Bloody Sunday. That's the day in March when King's marchers were met by riot police on Edmund Pettis Bridge. Now, this anniversary is a jubilee: we cross the bridge to celebrate how far we've come, with marching bands, banners and choirs.

But there's more work to be done. So we start every year's jubilee with a "Backwards March": Holding hands, I join other pastors and the formerly incarcerated to march backwards across the bridge, at the head of the parade. No one crosses the bridge until we've finished. Then the celebration continues.

Why do we march backwards? To remind us of everyone who's been left behind. We've got to go back and get them, and get things right, so we can move forward.

We march under this banner: "From the back of the bus to the front of the prison, the struggle continues."

Restoring Rights

I am formerly incarcerated myself. When I was released, I took the state of Alabama to court to regain my vote, then to restore this right to others. Because of these efforts, a quarter of a million in Alabama now have their voting rights restored.

But many still don't know they can vote. So since 2003, with help from the Drug Policy Alliance and Project South, I've gone inside jails to register voters. Because even if you're on the inside in Alabama, if you're not yet convicted, or convicted of a misdemeanor or a nonviolent drug offense, you can vote. No matter what you've been told.

Every Step Of The Way

These millions of men and women - the incarcerated and formerly incarcerated - are America's truly forgotten. They're not on anybody's list, or in anybody's poll; they've never been counted. No one ever thought we'd overcome the odds and vote.

Alabama's GOP has fought me every step of the way. Why? Because the last thing they want is for these millions of voters to regain their rights. One of the officials who opposed me most, Mike Hubbard, is now in prison for fraud. He can vote now, too, thanks to our efforts. You can't make this up.

Abolishing Slavery

Slavery still exists in the United States. That's because the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which abolished slavery in 1865, says it can still exist "as a punishment for crime." Prisoners all across this country are forced to work for free, or for pennies on the dollar.

But that's not all the Constitution says. The Eighth Amendment also bans "cruel and unusual punishment." What punishment is more more cruel and unusual than this modern form of slavery?

And in states all across the South, intentionally vague "Moral Turpitude" clauses bar those convicted of crimes from the vote. So in 2008, I sued Alabama and forced the state to allow me to extend voting rights to prisoners. In 2017, Alabama finally passed a law to clearly define crimes of "moral turpitude" which has re-enfranchised most of the 286,000 people with felony convictions in the state. But many of them still don't know they can vote. And hundreds of thousands more across the South - in Florida alone, there are 1.3 million - are waiting for this right to be restored.

So yes, there's work to be done.

Non-Violence Is Not Non-Movement

Now, we've launched #Free2Vote, a multi-state initiative with the People's Action Mass Liberation Campaign, Project South & the Southern Movement Assembly to register voters inside and outside of prisons and jails.

The only thing that declares your full citizenship is the right to vote. So we'll continue in Alabama, then move on to Florida, Georgia and other states of the South and North where voters have been disenfranchised through mass incarceration. A hundred million Americans are impacted by criminal convictions.

This is an insight I learned in Selma. Non-violence, one of our great lessons from Dr. King, has been misinterpreted by some to mean "non-movement." But the truth is, we need a powerful movement for voting rights, economic and racial justice, just as much today as we did fifty-three years ago.

So it's time to fulfill Dr. King's dream - to restore and revive his movement. We must go back, get what was lost, and move forward to restore the right to vote to America's truly forgotten men and women: the incarcerated, formerly incarcerated, those with criminal convictions as well as those sitting in jail who aren't convicted of anything, just waiting for trial.

In 1965, Martin Luther King, Jr. led marchers to the Dallas County Courthouse in Selma, Alabama to demand their right to vote. When they got there, they were arrested. That arrest, and the police brutality that followed it, galvanized the nation and forced passage of the Voting Rights Act.

Yet in 2018, many of us still do not have our right to vote. More than six million nationwide are disenfranchised because of state laws rooted in white supremacy. Millions more don't vote because someone lied and told us we can't, because we are or were in prison or have a conviction in our past.

So now we've come back to Selma to finish what King started: to recover and restore his movement.

Marching Backwards

I come to Selma every year on Bloody Sunday. That's the day in March when King's marchers were met by riot police on Edmund Pettis Bridge. Now, this anniversary is a jubilee: we cross the bridge to celebrate how far we've come, with marching bands, banners and choirs.

But there's more work to be done. So we start every year's jubilee with a "Backwards March": Holding hands, I join other pastors and the formerly incarcerated to march backwards across the bridge, at the head of the parade. No one crosses the bridge until we've finished. Then the celebration continues.

Why do we march backwards? To remind us of everyone who's been left behind. We've got to go back and get them, and get things right, so we can move forward.

We march under this banner: "From the back of the bus to the front of the prison, the struggle continues."

Restoring Rights

I am formerly incarcerated myself. When I was released, I took the state of Alabama to court to regain my vote, then to restore this right to others. Because of these efforts, a quarter of a million in Alabama now have their voting rights restored.

But many still don't know they can vote. So since 2003, with help from the Drug Policy Alliance and Project South, I've gone inside jails to register voters. Because even if you're on the inside in Alabama, if you're not yet convicted, or convicted of a misdemeanor or a nonviolent drug offense, you can vote. No matter what you've been told.

Every Step Of The Way

These millions of men and women - the incarcerated and formerly incarcerated - are America's truly forgotten. They're not on anybody's list, or in anybody's poll; they've never been counted. No one ever thought we'd overcome the odds and vote.

Alabama's GOP has fought me every step of the way. Why? Because the last thing they want is for these millions of voters to regain their rights. One of the officials who opposed me most, Mike Hubbard, is now in prison for fraud. He can vote now, too, thanks to our efforts. You can't make this up.

Abolishing Slavery

Slavery still exists in the United States. That's because the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which abolished slavery in 1865, says it can still exist "as a punishment for crime." Prisoners all across this country are forced to work for free, or for pennies on the dollar.

But that's not all the Constitution says. The Eighth Amendment also bans "cruel and unusual punishment." What punishment is more more cruel and unusual than this modern form of slavery?

And in states all across the South, intentionally vague "Moral Turpitude" clauses bar those convicted of crimes from the vote. So in 2008, I sued Alabama and forced the state to allow me to extend voting rights to prisoners. In 2017, Alabama finally passed a law to clearly define crimes of "moral turpitude" which has re-enfranchised most of the 286,000 people with felony convictions in the state. But many of them still don't know they can vote. And hundreds of thousands more across the South - in Florida alone, there are 1.3 million - are waiting for this right to be restored.

So yes, there's work to be done.

Non-Violence Is Not Non-Movement

Now, we've launched #Free2Vote, a multi-state initiative with the People's Action Mass Liberation Campaign, Project South & the Southern Movement Assembly to register voters inside and outside of prisons and jails.

The only thing that declares your full citizenship is the right to vote. So we'll continue in Alabama, then move on to Florida, Georgia and other states of the South and North where voters have been disenfranchised through mass incarceration. A hundred million Americans are impacted by criminal convictions.

This is an insight I learned in Selma. Non-violence, one of our great lessons from Dr. King, has been misinterpreted by some to mean "non-movement." But the truth is, we need a powerful movement for voting rights, economic and racial justice, just as much today as we did fifty-three years ago.

So it's time to fulfill Dr. King's dream - to restore and revive his movement. We must go back, get what was lost, and move forward to restore the right to vote to America's truly forgotten men and women: the incarcerated, formerly incarcerated, those with criminal convictions as well as those sitting in jail who aren't convicted of anything, just waiting for trial.