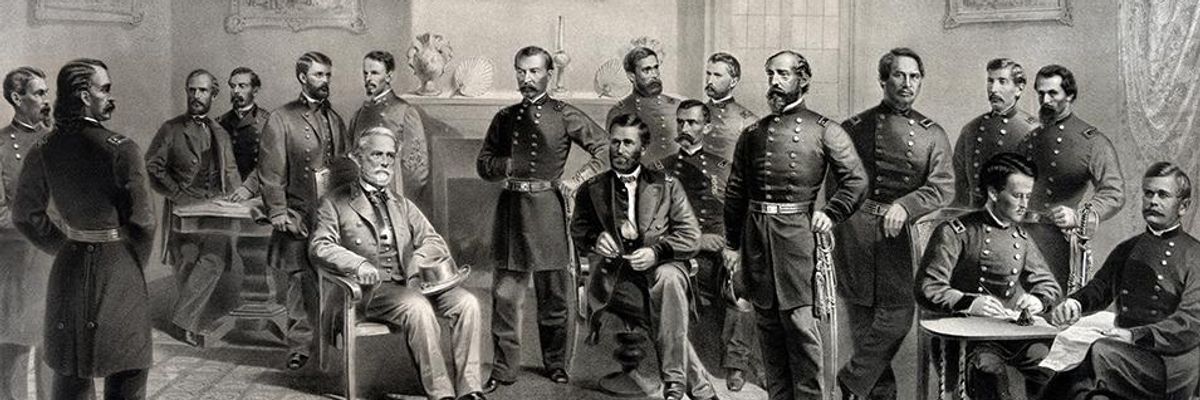

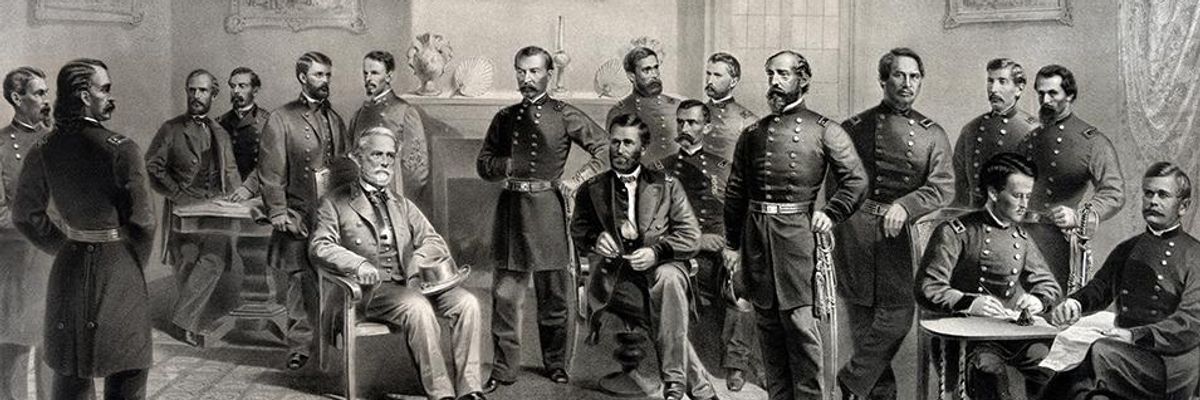

The Room in the McLean House, at Appomattox Court House, in which Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered to Gen. Ulysses S. Grant on April 9, 1865. (Library of Congress)

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

The Room in the McLean House, at Appomattox Court House, in which Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered to Gen. Ulysses S. Grant on April 9, 1865. (Library of Congress)

This Monday marks the 153rd anniversary of Robert E. Lee's surrender to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House in Virginia, ending the US Civil War. The Union commander told his men to respect the beaten rebels as fellow Americans, while President Lincoln urged reunion "with malice towards none" until his murder five days later.

We're still paying for this forbearance.

For while the slave-holding elite that had launched the Confederacy lost their power to enslave black people, their extreme hostility to our nation's common good lived on.

We often miss this because we see slavery as an old, traditional thing that the war finished off. That may be true for Lee's Virginia, but in the more militant Deep South the slaveholders were just getting started. They were the vanguard of an economic boom based on cotton.

The cotton planters had emerged during the War of 1812, when Andrew Jackson--one of the first in the business--wiped out much of the Creek Nation in Alabama. He continued as President in the 1830s, deporting the native peoples of the southeast at enormous expense in lives and resources. The planters who poured in frantically bought enslaved labor so that they could send as many bales as possible to the hellish factories of northern England.

About 30% of US exports in 1820, cotton shot past 50% ten years later and surged again in the 1850s. The biggest planters were the richest Americans; among them was Isaac Franklin of Louisiana, who owned 700 people and sold 1,000 more annually as the head of a human trafficking firm. Quickly spoiling their states through cash-crop monoculture, the planters pushed to invade Mexico in 1846 and for naval expansion around the globe.

Always eager to use government for their peculiar interests, slaveholders were constitutionally hostile to common schools, internal improvements, and other efforts by and for the public. They had little interest in the collective welfare of the people-at-large, because they held so many of those people as chattels.

For this same reason they felt benevolent for taking care of their "people" and betrayed whenever slaves ran away.

In 1860-61 the Deep South elite chose the continued expansion of slavery over the continued existence of the United States. They dragged cautious non-slaveholders into their treasonous project and were eventually beaten by the more developed and democratic North.

By halting this predatory class, the Union victory opened a window for revolutionary change: The Thirteenth Amendment banished slavery from US soil; Radical Republicans talked about seizing the planters' ill-gotten wealth; the Fifteenth Amendment ushered in black voting rights.

Above all, the Fourteenth Amendment nationalizing citizenship might have buried the slaveholders' way by securing the welfare of the people just because they were people, not because they were white, rich, or even "successful" in market terms. It could have raised every American to a new and dignified status, establishing their general well-being as the best compass for democratic progress.

But the moment passed. The forgiven planters held onto their estates, consigning the freed people to paltry wages. The nation reunified around a racial rather than a civic concept, agreeing that the South had been wrong to leave while the North had been wrong to emancipate. The Democrats regained the former Confederacy while the Republicans lost interest in it.

A new ruling class then emerged in a series of business mergers during the 1880s, supported by Social Darwinist dogma and thin readings of the Fourteenth Amendment.

For Gilded Age plutocrats as for antebellum planters, freedom was whatever they wanted to do. Democracy was whatever they told government to do. Once again, ruthless individuals trampled the common good and expected everyone to thank them for the crumbs.

We live in a second Gilded Age, a world of cruel inequality that makes Donald Trump seem genuine no matter how many lies he tells. At least he doesn't hide his contempt for anyone who isn't very, very grateful. At least he makes white people feel like members of a unified nation.

How fitting that the Koch Brothers now want to spin old yarns about the Civil War for a new generation of students. (Charter school students, if they have their way.) The lesson plans from their Bill of Rights Institute dismisses slavery as a small and shrinking flaw and scolds those who tried to transform the South after the war.

This is no hobby for the Kochs. It is an investment. It is an effort to airbrush our past until our present seems inescapable, to bury revolutionary hopes of self-evident rights and national solidarity under a soothing tale of things working out.

One way to fight back is to remember April 9th not as the final resolution of America's founding sin but rather as a fleeting victory over its fundamental problem.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

This Monday marks the 153rd anniversary of Robert E. Lee's surrender to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House in Virginia, ending the US Civil War. The Union commander told his men to respect the beaten rebels as fellow Americans, while President Lincoln urged reunion "with malice towards none" until his murder five days later.

We're still paying for this forbearance.

For while the slave-holding elite that had launched the Confederacy lost their power to enslave black people, their extreme hostility to our nation's common good lived on.

We often miss this because we see slavery as an old, traditional thing that the war finished off. That may be true for Lee's Virginia, but in the more militant Deep South the slaveholders were just getting started. They were the vanguard of an economic boom based on cotton.

The cotton planters had emerged during the War of 1812, when Andrew Jackson--one of the first in the business--wiped out much of the Creek Nation in Alabama. He continued as President in the 1830s, deporting the native peoples of the southeast at enormous expense in lives and resources. The planters who poured in frantically bought enslaved labor so that they could send as many bales as possible to the hellish factories of northern England.

About 30% of US exports in 1820, cotton shot past 50% ten years later and surged again in the 1850s. The biggest planters were the richest Americans; among them was Isaac Franklin of Louisiana, who owned 700 people and sold 1,000 more annually as the head of a human trafficking firm. Quickly spoiling their states through cash-crop monoculture, the planters pushed to invade Mexico in 1846 and for naval expansion around the globe.

Always eager to use government for their peculiar interests, slaveholders were constitutionally hostile to common schools, internal improvements, and other efforts by and for the public. They had little interest in the collective welfare of the people-at-large, because they held so many of those people as chattels.

For this same reason they felt benevolent for taking care of their "people" and betrayed whenever slaves ran away.

In 1860-61 the Deep South elite chose the continued expansion of slavery over the continued existence of the United States. They dragged cautious non-slaveholders into their treasonous project and were eventually beaten by the more developed and democratic North.

By halting this predatory class, the Union victory opened a window for revolutionary change: The Thirteenth Amendment banished slavery from US soil; Radical Republicans talked about seizing the planters' ill-gotten wealth; the Fifteenth Amendment ushered in black voting rights.

Above all, the Fourteenth Amendment nationalizing citizenship might have buried the slaveholders' way by securing the welfare of the people just because they were people, not because they were white, rich, or even "successful" in market terms. It could have raised every American to a new and dignified status, establishing their general well-being as the best compass for democratic progress.

But the moment passed. The forgiven planters held onto their estates, consigning the freed people to paltry wages. The nation reunified around a racial rather than a civic concept, agreeing that the South had been wrong to leave while the North had been wrong to emancipate. The Democrats regained the former Confederacy while the Republicans lost interest in it.

A new ruling class then emerged in a series of business mergers during the 1880s, supported by Social Darwinist dogma and thin readings of the Fourteenth Amendment.

For Gilded Age plutocrats as for antebellum planters, freedom was whatever they wanted to do. Democracy was whatever they told government to do. Once again, ruthless individuals trampled the common good and expected everyone to thank them for the crumbs.

We live in a second Gilded Age, a world of cruel inequality that makes Donald Trump seem genuine no matter how many lies he tells. At least he doesn't hide his contempt for anyone who isn't very, very grateful. At least he makes white people feel like members of a unified nation.

How fitting that the Koch Brothers now want to spin old yarns about the Civil War for a new generation of students. (Charter school students, if they have their way.) The lesson plans from their Bill of Rights Institute dismisses slavery as a small and shrinking flaw and scolds those who tried to transform the South after the war.

This is no hobby for the Kochs. It is an investment. It is an effort to airbrush our past until our present seems inescapable, to bury revolutionary hopes of self-evident rights and national solidarity under a soothing tale of things working out.

One way to fight back is to remember April 9th not as the final resolution of America's founding sin but rather as a fleeting victory over its fundamental problem.

This Monday marks the 153rd anniversary of Robert E. Lee's surrender to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House in Virginia, ending the US Civil War. The Union commander told his men to respect the beaten rebels as fellow Americans, while President Lincoln urged reunion "with malice towards none" until his murder five days later.

We're still paying for this forbearance.

For while the slave-holding elite that had launched the Confederacy lost their power to enslave black people, their extreme hostility to our nation's common good lived on.

We often miss this because we see slavery as an old, traditional thing that the war finished off. That may be true for Lee's Virginia, but in the more militant Deep South the slaveholders were just getting started. They were the vanguard of an economic boom based on cotton.

The cotton planters had emerged during the War of 1812, when Andrew Jackson--one of the first in the business--wiped out much of the Creek Nation in Alabama. He continued as President in the 1830s, deporting the native peoples of the southeast at enormous expense in lives and resources. The planters who poured in frantically bought enslaved labor so that they could send as many bales as possible to the hellish factories of northern England.

About 30% of US exports in 1820, cotton shot past 50% ten years later and surged again in the 1850s. The biggest planters were the richest Americans; among them was Isaac Franklin of Louisiana, who owned 700 people and sold 1,000 more annually as the head of a human trafficking firm. Quickly spoiling their states through cash-crop monoculture, the planters pushed to invade Mexico in 1846 and for naval expansion around the globe.

Always eager to use government for their peculiar interests, slaveholders were constitutionally hostile to common schools, internal improvements, and other efforts by and for the public. They had little interest in the collective welfare of the people-at-large, because they held so many of those people as chattels.

For this same reason they felt benevolent for taking care of their "people" and betrayed whenever slaves ran away.

In 1860-61 the Deep South elite chose the continued expansion of slavery over the continued existence of the United States. They dragged cautious non-slaveholders into their treasonous project and were eventually beaten by the more developed and democratic North.

By halting this predatory class, the Union victory opened a window for revolutionary change: The Thirteenth Amendment banished slavery from US soil; Radical Republicans talked about seizing the planters' ill-gotten wealth; the Fifteenth Amendment ushered in black voting rights.

Above all, the Fourteenth Amendment nationalizing citizenship might have buried the slaveholders' way by securing the welfare of the people just because they were people, not because they were white, rich, or even "successful" in market terms. It could have raised every American to a new and dignified status, establishing their general well-being as the best compass for democratic progress.

But the moment passed. The forgiven planters held onto their estates, consigning the freed people to paltry wages. The nation reunified around a racial rather than a civic concept, agreeing that the South had been wrong to leave while the North had been wrong to emancipate. The Democrats regained the former Confederacy while the Republicans lost interest in it.

A new ruling class then emerged in a series of business mergers during the 1880s, supported by Social Darwinist dogma and thin readings of the Fourteenth Amendment.

For Gilded Age plutocrats as for antebellum planters, freedom was whatever they wanted to do. Democracy was whatever they told government to do. Once again, ruthless individuals trampled the common good and expected everyone to thank them for the crumbs.

We live in a second Gilded Age, a world of cruel inequality that makes Donald Trump seem genuine no matter how many lies he tells. At least he doesn't hide his contempt for anyone who isn't very, very grateful. At least he makes white people feel like members of a unified nation.

How fitting that the Koch Brothers now want to spin old yarns about the Civil War for a new generation of students. (Charter school students, if they have their way.) The lesson plans from their Bill of Rights Institute dismisses slavery as a small and shrinking flaw and scolds those who tried to transform the South after the war.

This is no hobby for the Kochs. It is an investment. It is an effort to airbrush our past until our present seems inescapable, to bury revolutionary hopes of self-evident rights and national solidarity under a soothing tale of things working out.

One way to fight back is to remember April 9th not as the final resolution of America's founding sin but rather as a fleeting victory over its fundamental problem.