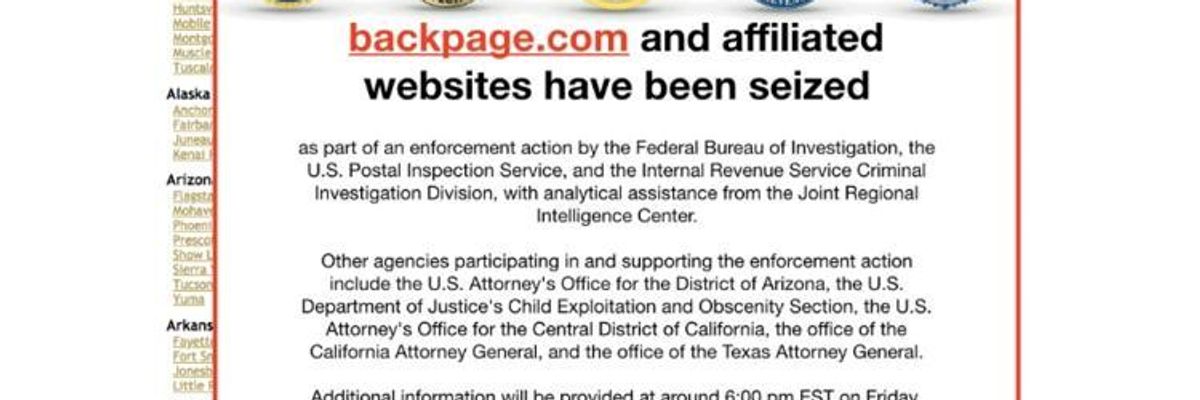

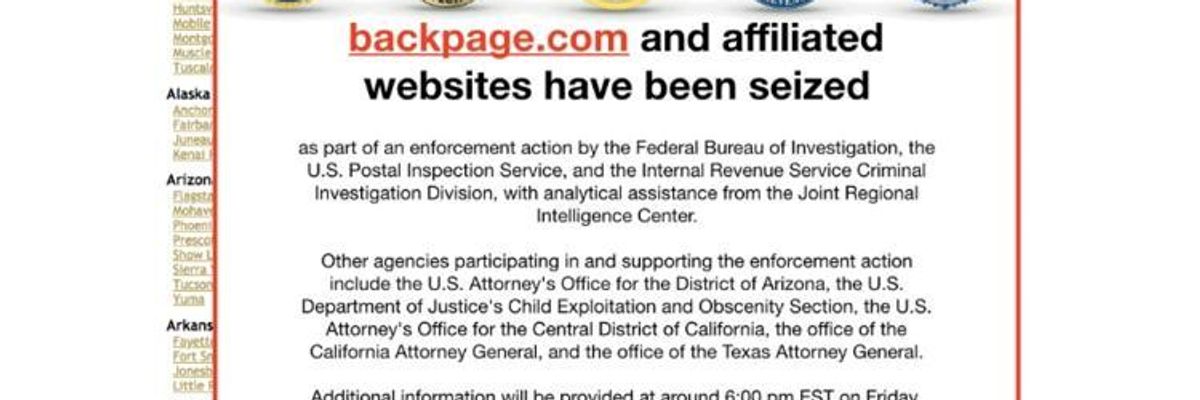

"So a forum whose founders made big bucks off trafficked minors doubled as a haven for the vulnerable." (Photo: Screenshot)

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Advocates left and right have applauded federal authorities' seizure of classified ads website Backpage.com as a victory for women in the sex trade. But who's angriest about the shutdown? Women in the sex trade.

The Backpage debate has crystallized the broader conversation around sex work, and it has also brought out an ugly strain of false feminism. Card-carrying progressives from Capitol Hill to Hollywood have leaped to denounce Backpage just as they've leaped before to denounce the prospect of legalizing prostitution. But it seems these avatars of female empowerment have failed to do the one thing that would actually empower the women they claim to defend: pay attention to what those women think.

Without a doubt, Backpage is a bad actor. Last year, a Senate subcommittee investigation discovered that the classified ads website had been editing language to disguise listings for underage girls instead of deleting them, and an expose by The Post revealed moderators actively solicited and even created similar ads. All this led to a bill currently awaiting President Trump's signature: the Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act, or FOSTA, which holds websites liable when their users advertise sex.

The problem is, for all its repulsive profiteering, Backpage was still sex workers' best shot at staying safe. Now they've taken to the Internet to tell stories of how the website spared them from exploitative forces operating in the even seedier underground of the sex economy. Backpage, former users say, freed them from dependency on pimps. The ability to cross-check clients with other sex workers, or even chat with clients ahead of time, helped them avoid abusive johns. The site also allowed them to schedule indoor dates and avoid the streets.

Card-carrying progressives from Capitol Hill to Hollywood have leaped to denounce Backpage just as they've leaped before to denounce the prospect of legalizing prostitution.

So a forum whose founders made big bucks off trafficked minors doubled as a haven for the vulnerable. That says less about Backpage than it does about this country's larger regime around sex work.

Many of the women who want to keep sites like Backpage around also make the case for decriminalizing sex work. They say they wouldn't have had to rely on the service at all if they could have operated in the open on their own terms -- and that openness would also allow them to report traffickers and other abusers to authorities without fear of reprisal. They also say a regulated industry would guarantee women who want to leave it eventually the wages they need to raise themselves from poverty.

The commentators and lawmakers who want to eliminate the supposed scourge of sex work altogether disagree. Some -- especially on the more conservative side of the spectrum -- declare that because the sale of sex is in itself degrading, the only acceptable outcome is to turn the market around it to rubble. Others, and progressives in particular, would rather avoid that thorny question, so they take a simpler tack: casting the wholesale destruction of the sex economy as the surest route to protecting trafficking victims. Many in both factions call themselves feminists.

The problem is, the route to protection is not so sure at all. For every study that purports to show a surge in trafficking where sex work is decriminalized, there's another that shows the opposite. And researchers have detailed the benefits that can come with legalization, from drops in sexually-transmitted diseases to drops in violence. (Rates of rape and gonorrhea both plummeted, for example, when Rhode Island accidentally legalized prostitution in 1980.)

Studies aside, one factor in the controversy stays constant: Though some individuals disagree, the majority of sex workers who have spoken out have done so to condemn laws that would drive what they do even deeper into the world's and the Internet's scariest corners.

From social conservatives, the refusal to hear these workers out is nothing new; moral disapprobation is mother's milk to them. But from credentialed liberals, it's incongruous. The same women who hope to take a shot at history in 2020, from Sens. Kamala D. Harris (D-Calif.) to Kirsten Gillibrand (D-N.Y.), can't shake the conventional doctrine that teaches them no one could possibly choose to sell sex -- not even over other low-wage work in industries also rife with abuse, from retail to hotels to textile manufacturing. They can't cast off the conviction that any woman who does make that choice needs saving.

But the real mark of feminism is trusting women to do what they want with their bodies. And it's at least listening to women about what sort of policy would help everyone exercise that kind of control. Sex workers are trying to talk to all of us right now. It just feels like no one wants to hear.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

Advocates left and right have applauded federal authorities' seizure of classified ads website Backpage.com as a victory for women in the sex trade. But who's angriest about the shutdown? Women in the sex trade.

The Backpage debate has crystallized the broader conversation around sex work, and it has also brought out an ugly strain of false feminism. Card-carrying progressives from Capitol Hill to Hollywood have leaped to denounce Backpage just as they've leaped before to denounce the prospect of legalizing prostitution. But it seems these avatars of female empowerment have failed to do the one thing that would actually empower the women they claim to defend: pay attention to what those women think.

Without a doubt, Backpage is a bad actor. Last year, a Senate subcommittee investigation discovered that the classified ads website had been editing language to disguise listings for underage girls instead of deleting them, and an expose by The Post revealed moderators actively solicited and even created similar ads. All this led to a bill currently awaiting President Trump's signature: the Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act, or FOSTA, which holds websites liable when their users advertise sex.

The problem is, for all its repulsive profiteering, Backpage was still sex workers' best shot at staying safe. Now they've taken to the Internet to tell stories of how the website spared them from exploitative forces operating in the even seedier underground of the sex economy. Backpage, former users say, freed them from dependency on pimps. The ability to cross-check clients with other sex workers, or even chat with clients ahead of time, helped them avoid abusive johns. The site also allowed them to schedule indoor dates and avoid the streets.

Card-carrying progressives from Capitol Hill to Hollywood have leaped to denounce Backpage just as they've leaped before to denounce the prospect of legalizing prostitution.

So a forum whose founders made big bucks off trafficked minors doubled as a haven for the vulnerable. That says less about Backpage than it does about this country's larger regime around sex work.

Many of the women who want to keep sites like Backpage around also make the case for decriminalizing sex work. They say they wouldn't have had to rely on the service at all if they could have operated in the open on their own terms -- and that openness would also allow them to report traffickers and other abusers to authorities without fear of reprisal. They also say a regulated industry would guarantee women who want to leave it eventually the wages they need to raise themselves from poverty.

The commentators and lawmakers who want to eliminate the supposed scourge of sex work altogether disagree. Some -- especially on the more conservative side of the spectrum -- declare that because the sale of sex is in itself degrading, the only acceptable outcome is to turn the market around it to rubble. Others, and progressives in particular, would rather avoid that thorny question, so they take a simpler tack: casting the wholesale destruction of the sex economy as the surest route to protecting trafficking victims. Many in both factions call themselves feminists.

The problem is, the route to protection is not so sure at all. For every study that purports to show a surge in trafficking where sex work is decriminalized, there's another that shows the opposite. And researchers have detailed the benefits that can come with legalization, from drops in sexually-transmitted diseases to drops in violence. (Rates of rape and gonorrhea both plummeted, for example, when Rhode Island accidentally legalized prostitution in 1980.)

Studies aside, one factor in the controversy stays constant: Though some individuals disagree, the majority of sex workers who have spoken out have done so to condemn laws that would drive what they do even deeper into the world's and the Internet's scariest corners.

From social conservatives, the refusal to hear these workers out is nothing new; moral disapprobation is mother's milk to them. But from credentialed liberals, it's incongruous. The same women who hope to take a shot at history in 2020, from Sens. Kamala D. Harris (D-Calif.) to Kirsten Gillibrand (D-N.Y.), can't shake the conventional doctrine that teaches them no one could possibly choose to sell sex -- not even over other low-wage work in industries also rife with abuse, from retail to hotels to textile manufacturing. They can't cast off the conviction that any woman who does make that choice needs saving.

But the real mark of feminism is trusting women to do what they want with their bodies. And it's at least listening to women about what sort of policy would help everyone exercise that kind of control. Sex workers are trying to talk to all of us right now. It just feels like no one wants to hear.

Advocates left and right have applauded federal authorities' seizure of classified ads website Backpage.com as a victory for women in the sex trade. But who's angriest about the shutdown? Women in the sex trade.

The Backpage debate has crystallized the broader conversation around sex work, and it has also brought out an ugly strain of false feminism. Card-carrying progressives from Capitol Hill to Hollywood have leaped to denounce Backpage just as they've leaped before to denounce the prospect of legalizing prostitution. But it seems these avatars of female empowerment have failed to do the one thing that would actually empower the women they claim to defend: pay attention to what those women think.

Without a doubt, Backpage is a bad actor. Last year, a Senate subcommittee investigation discovered that the classified ads website had been editing language to disguise listings for underage girls instead of deleting them, and an expose by The Post revealed moderators actively solicited and even created similar ads. All this led to a bill currently awaiting President Trump's signature: the Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act, or FOSTA, which holds websites liable when their users advertise sex.

The problem is, for all its repulsive profiteering, Backpage was still sex workers' best shot at staying safe. Now they've taken to the Internet to tell stories of how the website spared them from exploitative forces operating in the even seedier underground of the sex economy. Backpage, former users say, freed them from dependency on pimps. The ability to cross-check clients with other sex workers, or even chat with clients ahead of time, helped them avoid abusive johns. The site also allowed them to schedule indoor dates and avoid the streets.

Card-carrying progressives from Capitol Hill to Hollywood have leaped to denounce Backpage just as they've leaped before to denounce the prospect of legalizing prostitution.

So a forum whose founders made big bucks off trafficked minors doubled as a haven for the vulnerable. That says less about Backpage than it does about this country's larger regime around sex work.

Many of the women who want to keep sites like Backpage around also make the case for decriminalizing sex work. They say they wouldn't have had to rely on the service at all if they could have operated in the open on their own terms -- and that openness would also allow them to report traffickers and other abusers to authorities without fear of reprisal. They also say a regulated industry would guarantee women who want to leave it eventually the wages they need to raise themselves from poverty.

The commentators and lawmakers who want to eliminate the supposed scourge of sex work altogether disagree. Some -- especially on the more conservative side of the spectrum -- declare that because the sale of sex is in itself degrading, the only acceptable outcome is to turn the market around it to rubble. Others, and progressives in particular, would rather avoid that thorny question, so they take a simpler tack: casting the wholesale destruction of the sex economy as the surest route to protecting trafficking victims. Many in both factions call themselves feminists.

The problem is, the route to protection is not so sure at all. For every study that purports to show a surge in trafficking where sex work is decriminalized, there's another that shows the opposite. And researchers have detailed the benefits that can come with legalization, from drops in sexually-transmitted diseases to drops in violence. (Rates of rape and gonorrhea both plummeted, for example, when Rhode Island accidentally legalized prostitution in 1980.)

Studies aside, one factor in the controversy stays constant: Though some individuals disagree, the majority of sex workers who have spoken out have done so to condemn laws that would drive what they do even deeper into the world's and the Internet's scariest corners.

From social conservatives, the refusal to hear these workers out is nothing new; moral disapprobation is mother's milk to them. But from credentialed liberals, it's incongruous. The same women who hope to take a shot at history in 2020, from Sens. Kamala D. Harris (D-Calif.) to Kirsten Gillibrand (D-N.Y.), can't shake the conventional doctrine that teaches them no one could possibly choose to sell sex -- not even over other low-wage work in industries also rife with abuse, from retail to hotels to textile manufacturing. They can't cast off the conviction that any woman who does make that choice needs saving.

But the real mark of feminism is trusting women to do what they want with their bodies. And it's at least listening to women about what sort of policy would help everyone exercise that kind of control. Sex workers are trying to talk to all of us right now. It just feels like no one wants to hear.