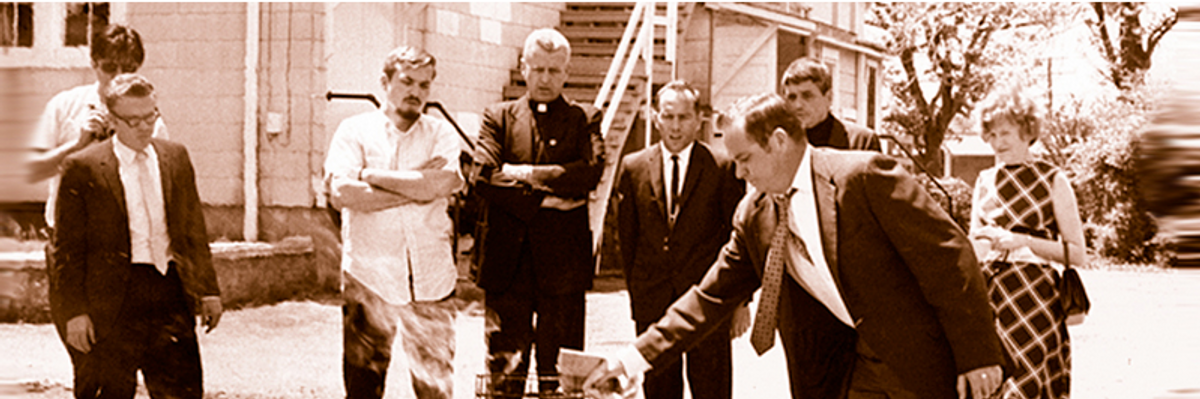

"Our apologies, good friends, for the fracture of good order, the burning of paper instead of children." (Photo: Screenshot/Catonsville9.org)

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

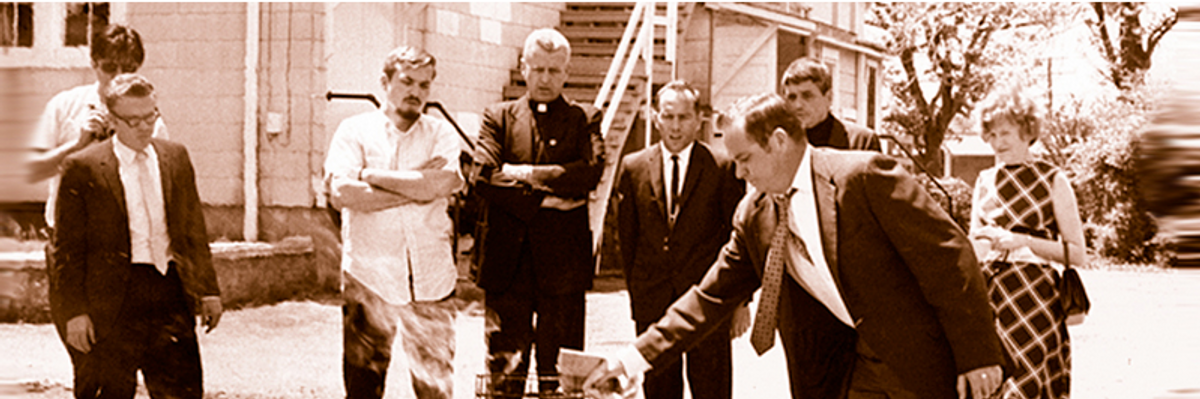

"Our apologies, good friends, for the fracture of good order, the burning of paper instead of children." (Photo: Screenshot/Catonsville9.org)

On May 17, 1968, along the main road that runs through the Baltimore suburb of Catonsville, Maryland, a group of Catholic activists stood around a small fire, praying and singing. They had gone into the local draft board office and taken 378 draft records, for the young men in the 1-A category who were most likely to get drafted to go to war in Vietnam. They set fire to the draft records using homemade napalm, made from gasoline and laundry soap, to symbolize the U.S. military's use of napalm on Vietnamese civilians. Six weeks earlier, on April 4, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis. Robert F. Kennedy's killing would follow not long after. The war was raging, with no end in sight, and these nine, including two brothers, Dan and Phil Berrigan, both Catholic priests, were engaging in an act of nonviolent civil disobedience to oppose it. The Catonsville Nine patiently waited until the Baltimore County police arrived to arrest them. The fire was put out, but this bold action was a spark, inspiring similar protests around the country, fueling the anti-war movement.

"Our apologies, good friends, for the fracture of good order, the burning of paper instead of children," Father Dan Berrigan wrote in a statement explaining the action, adding, "we shall, beyond doubt, be placed behind bars for some portion of our natural lives."

Among the nine were Marjorie Melville, her husband, Thomas Melville, and John Hogan. Years before the Catonsville protest, the three of them, as members of the Maryknoll order of priests, brothers and nuns, had been in Guatemala following the U.S.-backed overthrow, in 1954, of the democratically elected president, Jacobo Arbenz. Because of their sympathy for the poor and the revolutionary cause in Guatemala, the three were expelled. Marjorie and Thomas left their religious order and married.

The other woman who participated in the Catonsville action was Mary Moylan, a registered nurse who had worked in Uganda. She later said her motivation to participate was because she wanted to be a part of a "celebration of life, not a dance of death."

The nine were prosecuted and, in 1970, given prison sentences of up to three years behind bars. Dan Berrigan went underground, evading arrest for four months. At a recent gathering of Right Livelihood Award laureates in Santa Cruz, California, Daniel Ellsberg, the legendary whistleblower who released the Pentagon Papers, told us that the decision he and his wife Patricia made to go underground in 1971 was directly inspired by Dan Berrigan's action a year earlier. Berrigan ultimately served a year and a half for the Catonsville protest.

As demonstrated in the documentary film "Hit and Stay" -- a pun on the phrase "hit and run," highlighting how these activists chose to stay, awaiting arrest -- the Catonsville Nine, along with the Baltimore Four protest the preceding year (when Phil Berrigan and three others poured their own blood on draft files in Baltimore), prompted a wave of similar acts of anti-war, nonviolent civil disobedience. It inspired more radical tactics, escalating the movement to end the Vietnam War.

It also led to a global protest effort to end the threat of nuclear war, the Plowshares movement. Plowshares actions are inspired by a line from the Old Testament, Isaiah 2:4: "They will hammer their swords into plowshares and their spears into pruning hooks. Nation will no longer fight against nation, nor train for war anymore."

In 1980, Dan Berrigan, again with his brother Phil and others, broke into a General Electric missile plant in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania. They hammered on missile nose cones, damaging them beyond repair, and poured their blood on the damaged parts.

The 50th anniversary of the Catonsville Nine action was recently held, just blocks from the site where these committed activists burned the draft records. In 1968, the local draft board rented an office on the second floor of the local Knights of Columbus building. The Knights is a conservative Catholic organization and wanted nothing to do with the commemoration, so the official Maryland state historical roadside marker sits about 100 yards away, in front of the public library.

At the marker's dedication ceremony, one of the only two surviving members of the Catonsville Nine, Marjory Melville, walked with us to the scene of the "crime." When asked if, in retrospect, she would have done anything differently, she surveyed the empty parking lot, smiling, and said, "I would do it all over again." Her commitment was reminiscent of Dan Berrigan's, when he was finally arrested after being underground. A reporter asked, "What are your future plans?" Smiling, in handcuffs, Berrigan flashed a peace sign and shouted, "Resistance!"

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

On May 17, 1968, along the main road that runs through the Baltimore suburb of Catonsville, Maryland, a group of Catholic activists stood around a small fire, praying and singing. They had gone into the local draft board office and taken 378 draft records, for the young men in the 1-A category who were most likely to get drafted to go to war in Vietnam. They set fire to the draft records using homemade napalm, made from gasoline and laundry soap, to symbolize the U.S. military's use of napalm on Vietnamese civilians. Six weeks earlier, on April 4, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis. Robert F. Kennedy's killing would follow not long after. The war was raging, with no end in sight, and these nine, including two brothers, Dan and Phil Berrigan, both Catholic priests, were engaging in an act of nonviolent civil disobedience to oppose it. The Catonsville Nine patiently waited until the Baltimore County police arrived to arrest them. The fire was put out, but this bold action was a spark, inspiring similar protests around the country, fueling the anti-war movement.

"Our apologies, good friends, for the fracture of good order, the burning of paper instead of children," Father Dan Berrigan wrote in a statement explaining the action, adding, "we shall, beyond doubt, be placed behind bars for some portion of our natural lives."

Among the nine were Marjorie Melville, her husband, Thomas Melville, and John Hogan. Years before the Catonsville protest, the three of them, as members of the Maryknoll order of priests, brothers and nuns, had been in Guatemala following the U.S.-backed overthrow, in 1954, of the democratically elected president, Jacobo Arbenz. Because of their sympathy for the poor and the revolutionary cause in Guatemala, the three were expelled. Marjorie and Thomas left their religious order and married.

The other woman who participated in the Catonsville action was Mary Moylan, a registered nurse who had worked in Uganda. She later said her motivation to participate was because she wanted to be a part of a "celebration of life, not a dance of death."

The nine were prosecuted and, in 1970, given prison sentences of up to three years behind bars. Dan Berrigan went underground, evading arrest for four months. At a recent gathering of Right Livelihood Award laureates in Santa Cruz, California, Daniel Ellsberg, the legendary whistleblower who released the Pentagon Papers, told us that the decision he and his wife Patricia made to go underground in 1971 was directly inspired by Dan Berrigan's action a year earlier. Berrigan ultimately served a year and a half for the Catonsville protest.

As demonstrated in the documentary film "Hit and Stay" -- a pun on the phrase "hit and run," highlighting how these activists chose to stay, awaiting arrest -- the Catonsville Nine, along with the Baltimore Four protest the preceding year (when Phil Berrigan and three others poured their own blood on draft files in Baltimore), prompted a wave of similar acts of anti-war, nonviolent civil disobedience. It inspired more radical tactics, escalating the movement to end the Vietnam War.

It also led to a global protest effort to end the threat of nuclear war, the Plowshares movement. Plowshares actions are inspired by a line from the Old Testament, Isaiah 2:4: "They will hammer their swords into plowshares and their spears into pruning hooks. Nation will no longer fight against nation, nor train for war anymore."

In 1980, Dan Berrigan, again with his brother Phil and others, broke into a General Electric missile plant in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania. They hammered on missile nose cones, damaging them beyond repair, and poured their blood on the damaged parts.

The 50th anniversary of the Catonsville Nine action was recently held, just blocks from the site where these committed activists burned the draft records. In 1968, the local draft board rented an office on the second floor of the local Knights of Columbus building. The Knights is a conservative Catholic organization and wanted nothing to do with the commemoration, so the official Maryland state historical roadside marker sits about 100 yards away, in front of the public library.

At the marker's dedication ceremony, one of the only two surviving members of the Catonsville Nine, Marjory Melville, walked with us to the scene of the "crime." When asked if, in retrospect, she would have done anything differently, she surveyed the empty parking lot, smiling, and said, "I would do it all over again." Her commitment was reminiscent of Dan Berrigan's, when he was finally arrested after being underground. A reporter asked, "What are your future plans?" Smiling, in handcuffs, Berrigan flashed a peace sign and shouted, "Resistance!"

On May 17, 1968, along the main road that runs through the Baltimore suburb of Catonsville, Maryland, a group of Catholic activists stood around a small fire, praying and singing. They had gone into the local draft board office and taken 378 draft records, for the young men in the 1-A category who were most likely to get drafted to go to war in Vietnam. They set fire to the draft records using homemade napalm, made from gasoline and laundry soap, to symbolize the U.S. military's use of napalm on Vietnamese civilians. Six weeks earlier, on April 4, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis. Robert F. Kennedy's killing would follow not long after. The war was raging, with no end in sight, and these nine, including two brothers, Dan and Phil Berrigan, both Catholic priests, were engaging in an act of nonviolent civil disobedience to oppose it. The Catonsville Nine patiently waited until the Baltimore County police arrived to arrest them. The fire was put out, but this bold action was a spark, inspiring similar protests around the country, fueling the anti-war movement.

"Our apologies, good friends, for the fracture of good order, the burning of paper instead of children," Father Dan Berrigan wrote in a statement explaining the action, adding, "we shall, beyond doubt, be placed behind bars for some portion of our natural lives."

Among the nine were Marjorie Melville, her husband, Thomas Melville, and John Hogan. Years before the Catonsville protest, the three of them, as members of the Maryknoll order of priests, brothers and nuns, had been in Guatemala following the U.S.-backed overthrow, in 1954, of the democratically elected president, Jacobo Arbenz. Because of their sympathy for the poor and the revolutionary cause in Guatemala, the three were expelled. Marjorie and Thomas left their religious order and married.

The other woman who participated in the Catonsville action was Mary Moylan, a registered nurse who had worked in Uganda. She later said her motivation to participate was because she wanted to be a part of a "celebration of life, not a dance of death."

The nine were prosecuted and, in 1970, given prison sentences of up to three years behind bars. Dan Berrigan went underground, evading arrest for four months. At a recent gathering of Right Livelihood Award laureates in Santa Cruz, California, Daniel Ellsberg, the legendary whistleblower who released the Pentagon Papers, told us that the decision he and his wife Patricia made to go underground in 1971 was directly inspired by Dan Berrigan's action a year earlier. Berrigan ultimately served a year and a half for the Catonsville protest.

As demonstrated in the documentary film "Hit and Stay" -- a pun on the phrase "hit and run," highlighting how these activists chose to stay, awaiting arrest -- the Catonsville Nine, along with the Baltimore Four protest the preceding year (when Phil Berrigan and three others poured their own blood on draft files in Baltimore), prompted a wave of similar acts of anti-war, nonviolent civil disobedience. It inspired more radical tactics, escalating the movement to end the Vietnam War.

It also led to a global protest effort to end the threat of nuclear war, the Plowshares movement. Plowshares actions are inspired by a line from the Old Testament, Isaiah 2:4: "They will hammer their swords into plowshares and their spears into pruning hooks. Nation will no longer fight against nation, nor train for war anymore."

In 1980, Dan Berrigan, again with his brother Phil and others, broke into a General Electric missile plant in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania. They hammered on missile nose cones, damaging them beyond repair, and poured their blood on the damaged parts.

The 50th anniversary of the Catonsville Nine action was recently held, just blocks from the site where these committed activists burned the draft records. In 1968, the local draft board rented an office on the second floor of the local Knights of Columbus building. The Knights is a conservative Catholic organization and wanted nothing to do with the commemoration, so the official Maryland state historical roadside marker sits about 100 yards away, in front of the public library.

At the marker's dedication ceremony, one of the only two surviving members of the Catonsville Nine, Marjory Melville, walked with us to the scene of the "crime." When asked if, in retrospect, she would have done anything differently, she surveyed the empty parking lot, smiling, and said, "I would do it all over again." Her commitment was reminiscent of Dan Berrigan's, when he was finally arrested after being underground. A reporter asked, "What are your future plans?" Smiling, in handcuffs, Berrigan flashed a peace sign and shouted, "Resistance!"