The topic of economic inequality can appear complex, with many nuanced causes and outcomes. But while the two of us actively engage in that debate, we also strongly believe that there is one overarching factor that must not be, but often is, overlooked: worker bargaining power. On Labor Day, this problem of the long-term decline in workers' ability to bargain for a fair share of the growth they have helped generate deserves a closer look.

There is, of course, a direct link between less worker clout and the decline in union coverage. In addition to directly empowering workers at the workplace, unions have played a central role in the drive for a wide variety of policy measures to ensure that everyone benefits from prosperity, which is the opposite outcome of rising inequality. This list includes Social Security, Medicare, paid family leave, civil rights legislation, fairer tax policy and higher minimum wages.

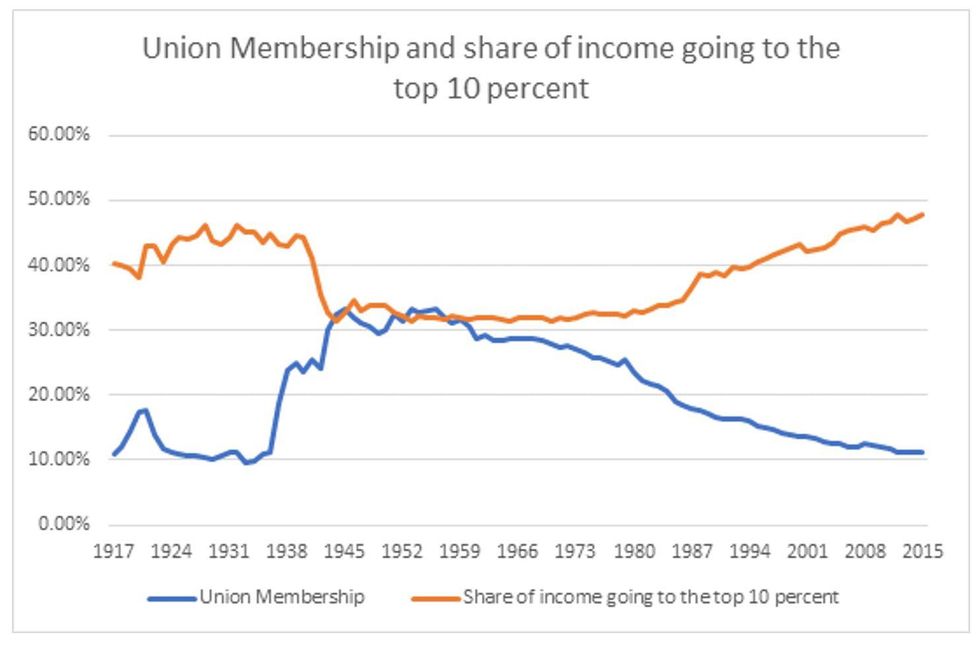

This view has been further buttressed by recent research using new data showing a strong connection between union strength and a more equal distribution of income (see figure), a link that makes the sharp decline in union membership over the past four decades particularly disturbing.

This decline has not been an accident. The right has quite explicitly targeted unions with an array of anti-union policies, the most recent of which have been "right-to-work"

laws. These prohibit contracts that require all the workers at a unionized workplace to share in the cost of representation.

The impact of anti-union policy can be seen by the differing experiences of Canada and the United States over this period. While the unionization rate in the United States dropped from roughly 20 percent in the late 1970s to just over 10 percent most recently, unionization rates in Canada have edged down only slightly over this period and still exceed 31 percent.

The fact that unions continue to thrive in a country with a very similar culture and economy indicates that there is nothing inevitable about the decline in unions in the United States. It was deliberate policy.

Given that powerful, vested interests are behind the decline in unions, reversing this decline will be a serious challenge, one that requires worker-friendly policies and new forms of worker representation, such as centralized bargaining. For example, instead of organizing one restaurant at a time, unions must push for collective bargaining rights for restaurant workers across their industry. It also will require reaching out to all types of workers, not just those in construction, factories or lower-paid services.

Two decades ago, we worked together at the Economic Policy Institute (EPI). EPI was and is a great place to work, but we felt it was important for the staff to gain an institutionalized voice. We helped organize a union that affiliated with the International Federation of Professional and Technical Engineers (IFPTE, Local 70).

The process of organizing was interesting, because many of our co-workers at EPI thought of themselves as professionals for whom unions really didn't make much sense. After much discussion, everyone came to agree that a union was a good idea. The vote for the union was unanimous. (We are also pleased to report that management was fully cooperative and happy to respect our decision.)

Since then, Local 70 has organized a number of Washington-based nonprofits. It now has well over 300 members. If some current organizing drives succeed, Local 70, which has since been restructured as the Nonprofit Professional Employees Union (NPEU), will have more than 500 members.

We are well aware that in a labor force of more than 150 million, 500 workers isn't exactly a game-changer. But the journey of 1,000 miles starts with one step. It is essential that unions make inroads into the types of workers organized by NPEU if they are to regain the sort of influence and power they had in prior decades.

Unions will continue to be important in traditional strongholds such as manufacturing and construction. But as the workforce becomes more educated, a powerful union movement will need to include many workers with college and advanced degrees.

If that sounds peculiar, in countries such as Denmark and Sweden, which have a far more equal distribution of income than the United States, more than 70 percent of the workforces are represented by unions. In these countries, it is the norm for people working in white-collar jobs, including many with college degrees, to be represented by unions.

The United States may never approach Scandinavian rates of unionization, but if we are even going to get back to 1970 rates, unions will have to make inroads into new areas. Part of that story has to mean organizing professional workers. On this day in particular, we proudly recall our small contribution to this effort.