SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

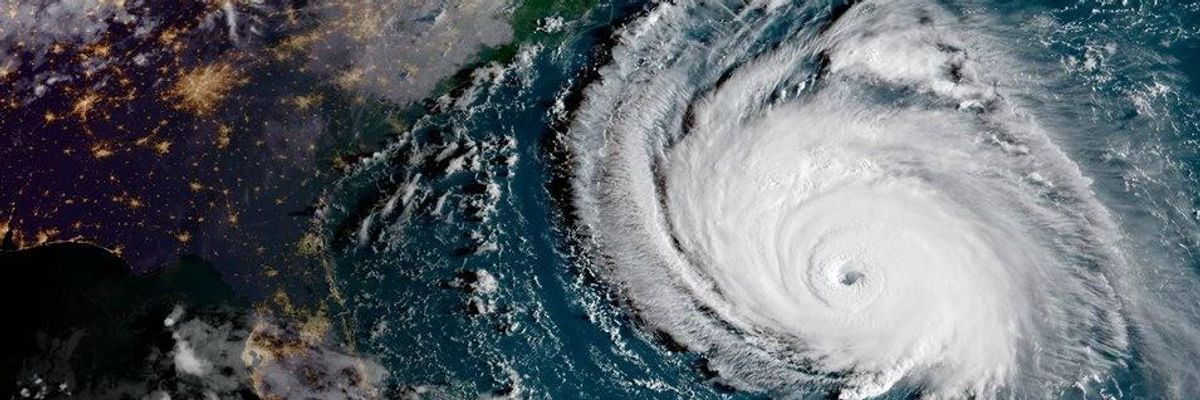

People don't fully understand the true nature of the threat that climate change poses, and the press - when they bother to cover it - understates it. (Photo: CIRA/RAAMB)

Climate change catastrophe is upon us. We see it in the record-breaking floods from storms like Florence, and in the record-breaking fires across the US once again this year. But the media - which barely mentioned the link between these catastrophes and climate change -- is preparing to move on to the next new, new, thing. Can't blame them. Trump and the Republicans are providing enough fodder to feed a thousand news cycles with daily outrages that keep the country on the edge of chaos.

But here's the thing - climate change will affect us more profoundly, more negatively, and sooner than anything we've been led to believe. What we're seeing now is just a taste of what the future holds, and the disasters we're causing today with our continued use of fossil fuels will soon be a permanent feature of our existence, irrevocable in anything other than geologic time, if we don't act immediately.

What we're seeing now is just a taste of what the future holds, and the disasters we're causing today with our continued use of fossil fuels will soon be a permanent feature of our existence, irrevocable in anything other than geologic time, if we don't act immediately.

Here's why.

We're ignoring feedbacks in our forecasts. Back in 2004, in an article in the Baltimore Sun, I warned that the rapid warming in the Arctic had the potential to release methane from clathrates and permafrost, speeding up the rate and extent of warming. By 2006, I noted that there was evidence that this particular feedback had started already.

It's been known for some time that feedbacks cause earth systems to respond non-linearly - that is to experience extreme and swift reactions well beyond what our models forecast. Such rapid warming can be found throughout the geologic record, and two of the most disruptive, the Permian die-off and the Paleocene/Eocene thermal Maximum (PETM), share the root cause of today's warming - sudden increases in the amount of atmospheric carbon. Now, rapid is a relative term in geology. Something on the order of a thousand years is the blink of an eye gauged against geologic time. And both these events took centuries to unfold, and eons to reverse.

But when it comes to carbon emissions, humans are giving "rapid" a whole new meaning. For example, during the PETM warming, unusually intense and sustained volcanic activity was releasing about 0.2 of a gigatonne per year, whereas today, humans are releasing about 10 gigatonnes per year.

A recent report published in the prestigious Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, identifies ten feedbacks that could - and absent immediate action, likely will - increase the pace and extent of warming; something they refer to as the "Hothouse Earth" pathway. Hothouse Earth is not a planet compatible with the world humans evolved in, nor is it capable of sustaining civilization as we know it. For example, under the Hothouse Earth pathway, sea level would ultimately rise by as much as 60 meters (about 197 feet) and stay that way for millennia. This would inundate virtually every coastal city in the world, and displace close to 3 billion people. And these billions of refugees would come on top of others already displaced by heat, drought, disease, storms, hunger and the political unrest they would cause.

Feedbacks are the tail wagging the dog - together, they could dwarf the warming we're forecasting from just human emissions without feedbacks. Despite the fact that we've known about them for decades, they aren't considered by the IPCC forecasts, they're rarely covered in the news, they're routinely ignored in policy discussions, and we are dangerously close to triggering some of the worst of these feedbacks - if we haven't already.

Carbon budgets employ safety factors that aren't safe in order to give us the illusion that we have more time to act to avoid catastrophic warming. There's been a lot written about the Paris Agreement and why it may not have been adequate to stop dangerous warming, even before Trump withdrew the US and backtracked on Obama's carbon reduction measures. People pointed out that two degrees was too high to avoid feedbacks, that the measures were voluntary, that fully implemented it would still allow temperature increases of 3.5 degrees C or more. All legitimate, all deeply concerning. And the fact that countries are now behind in terms of meeting their targets shows these concerns were valid.

But the use of carbon budgets may be the least understood and most serious flaw in the Agreement - in fact, carbon budgets are the basis for all IPCC forecasts and they expose us to extraordinary risks.

We'll get to the details in a moment.

But first, a word about risk management. Typically, if the consequences of something are irreversible, ubiquitous, and catastrophic, we use extremely conservative safety factors when we design something. For example, airplanes and bridges are engineered with huge margins of safety and a lot of redundant systems. They are as close as we can come to fail-safe. But when it comes to protecting the Earth from the ravages of climate change, we're accepting risks of failure we wouldn't accept for a washing machine, a toaster or a blender.

When it comes to protecting the Earth from the ravages of climate change, we're accepting risks of failure we wouldn't accept for a washing machine, a toaster or a blender.

Now the details. Carbon budgets are established to determine the maximum amount of GHG we can emit, and for how long, to reach a given atmospheric level of GHG concentrations needed to limit warming to a given temperature increase. So, for example, if we seek to limit temperature increases to less than 2degC, then we have to limit GHG emissions to a level that avoids atmospheric concentrations sufficient to cause warming to exceed that limit.

In establishing carbon budgets, the IPCC used a series of probabilities for staying below the target temperature of 2 C (3.6 F). The probabilities they used were a 66 percent likelihood of meeting the target, a 50 percent likelihood of doing so, and a 30 percent likelihood. What this actually means is that 66 percent of the models forecast temperatures below the target level, or 50 percent of them do, or 30 percent of them do.

Notice what's not included in the carbon budgets the IPCC considered: a confidence level of 100 percent or even 90 percent. Now, think about this for a moment. We are using margins of safety for the future viability of our planet's life-support systems that we wouldn't tolerate in almost any other area of our life. Would you board a plane with a 33 percent chance of crashing? Cross a bridge that has only a 66 percent chance of holding up? No. You wouldn't.

So why is the 100 percent probability of making our goal not included in the IPCC's scenarios -- or the 90 percent probability for that matter? Answer: because we've already blown past the carbon emissions that would achieve either one. So now, we're stuck with the planetary equivalent of taking risks equal to playing Russian roulette with two bullets in the chamber. You'd think this would be a big deal, something worth talking about.

But of course, you'd be wrong.

By specifying a 66 percent probability of meeting the 2degC target, rather than 100 percent or 90 percent, we can appear to buy ourselves a lot of time. The lower we set the probability of staying below 2degC, the higher the allowable carbon budget and the more time we have to get off it. Of course, that doesn't actually give us more time--but it does provide the appearance of doing so.

So, higher odds of success require lower carbon budgets and give us less time, lower odds of success allow more carbon to be released over a longer time.

Now let's do some numbers.

If we wanted to have a 66 percent probability of staying below 1.5degC, our total carbon budget would be 2,250 tonnes of carbon dioxide. By the end of 2017, we burned through all but about 160 billion tonnes of that budget. Since we are emitting about forty billion tonnes per year (about forty-four billion US tons), we will blow through the budget in 2021. If we were to choose a more rational level of risk management, such as a 90 percent or 100 percent likelihood of preventing global Armageddon, we would have had to start acting a couple of decades ago, since we exceeded those limits in 2013.

Contrast this with the carbon budget based on a 66 percent probability of staying below 2degC, or 2,900 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide (GtCO2e). By 2017, we would appear to have nearly 810 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide emissions left, or twenty years' worth.

Playing craps with the planet we live on is--to say the least--irresponsible. Using an inadequate margin of safety doesn't actually increase the time we have to act to avoid catastrophic changes to our climate and seas, it merely appears to do so.

So the press ignores it; and we drift happily towards a rendezvous with an ecological Armageddon. But this is so inside baseball, that almost no one understands it except those making and using the carbon budgets. So the press ignores it; and we drift happily towards a rendezvous with an ecological Armageddon.

Avoiding doom and gloom when the news was gloomy. So why don't scientists sound the alarm about the full range of risk we're exposing ourselves and our children to? Well, as the NAS study shows, some are beginning to. James Hansen, Kevin Anderson, Michael Mann and several others have been trying to tell folks the dire consequences of climate change for some time now.

But in general, scientists and journalists have avoided spreading "doom and gloom," preferring to sound a more hopeful and optimistic tone.

As I noted last year, when David Wallace Wells wrote The Uninhabitable Earth - a truly worst case summary of what our world was becoming -- he was roundly criticized by scientists for spreading doom and gloom. Aside from one error about the magnitude of warming that melting perma-frost might cause, Wallace-Wells article used plausible worst-case forecasts to paint the picture of the world we are heading toward. And as the Scientific American noted, when you ground-truth past forecasts against what actually happened, the best fit comes from using worst-case or even worse than worst-case forecasts, so he was on sound ground.

Yet such was the blow back that Wallace-Wells has been taking a much softer and more optimistic tone lately.

I call Bullshit on the anti-doom and gloomers. Again, standard risk management strategies suggest we use the utmost caution - which is to say, assume the worst, and spare no expense in adopting policies which will prevent an outcome that is potentially ubiquitous, cataclysmic and irreversible. Nothing, with the possible exception of an all-out nuclear war, fits that category better than climate change.

But because of what James Hansen calls scientific reticence, scientists have been reluctant to raise alarms, and when they have, many were not particularly good at it, couching there concerns in the careful language of science.

As a result, people don't fully understand the true nature of the threat that climate change poses, and the press - when they bother to cover it - understates it.

Neoclassical economics provides a convenient excuse for inaction. Ever since Hansen delivered his testimony before the Senate on the threat of climate change in 1988, economists and deniers using economic arguments, have been telling us that taking action to prevent climate change is too expensive. This was never a credible argument, given that what was at stake were trillions of dollars of real estate, hundreds of millions dead, loss of priceless habitat, mass extinctions, epidemics, unprecedented drought, spreading pestilence and widespread famine. But the conventions of economics - especially the practice of discounting future benefits - grossly undervalues the benefits to future generations from present expenditures. That is, economic analyses tend to conclude that money spent today to protect future generations is rarely worth it.

Discounting in economics has been the stuff of PhD Thesis and Nobel Prizes, but David Roberts has written an accessible explanation of why it's important and how profoundly it can distort policy in an article entitled, "Discount Rates: A boring thing you should know about, (with otters!)."

There are other problems with economics - it presumes everyone is behaving rationally, then measures "rational" as maximizing their returns and these returns are measured in currency. As psychologist Daniel Kahneman and others have proved, humans simply aren't all that rational when it comes to real world economic behavior, and they measure returns in all kinds of ways. In fact, Kahneman won the Nobel prize in economics for his work showing the fallacy of the perfectly rational agent.

Economists chose to make simplifying assumptions about human rationality so that they could create elegant and often quite complex mathematical models about how the economy works - something another Nobel prize winning economist, Paul Krugman, called mistaking beauty for truth.

It never made sense to argue that tackling climate change would impose a net cost on society to avoid the most expensive catastrophe in human history, but now that renewables are the cheapest source of power, arguing against climate mitigation and propping up fossil fuel investments hurts the economy and costs us jobs today - right now.

If past is prologue, the media will soon move on, leaving the greatest threat humanity has ever faced virtually uncovered. As the flood waters recede, and the smoke covering the western United States dissipates, what little coverage climate change gets in the media will slow to a trickle. It's hard to compete with Trump's daily outrages, or the Republican Congress's epic hypocrisy. And make no mistake, they pose a clear and present danger to the institutions that sustain what's left of our democracy. And the Democrats' internal battle for identity - a fight between progressive values and the same old money ball politics - is endlessly fascinating.

But the consequences of the inside-the-beltway political games, interesting as they are, pale in comparison to the consequences of ignoring or underestimating the consequences of climate change. An ecologically viable planet capable of sustaining civilization is, after all, a prerequisite to all the other games humans play.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

Climate change catastrophe is upon us. We see it in the record-breaking floods from storms like Florence, and in the record-breaking fires across the US once again this year. But the media - which barely mentioned the link between these catastrophes and climate change -- is preparing to move on to the next new, new, thing. Can't blame them. Trump and the Republicans are providing enough fodder to feed a thousand news cycles with daily outrages that keep the country on the edge of chaos.

But here's the thing - climate change will affect us more profoundly, more negatively, and sooner than anything we've been led to believe. What we're seeing now is just a taste of what the future holds, and the disasters we're causing today with our continued use of fossil fuels will soon be a permanent feature of our existence, irrevocable in anything other than geologic time, if we don't act immediately.

What we're seeing now is just a taste of what the future holds, and the disasters we're causing today with our continued use of fossil fuels will soon be a permanent feature of our existence, irrevocable in anything other than geologic time, if we don't act immediately.

Here's why.

We're ignoring feedbacks in our forecasts. Back in 2004, in an article in the Baltimore Sun, I warned that the rapid warming in the Arctic had the potential to release methane from clathrates and permafrost, speeding up the rate and extent of warming. By 2006, I noted that there was evidence that this particular feedback had started already.

It's been known for some time that feedbacks cause earth systems to respond non-linearly - that is to experience extreme and swift reactions well beyond what our models forecast. Such rapid warming can be found throughout the geologic record, and two of the most disruptive, the Permian die-off and the Paleocene/Eocene thermal Maximum (PETM), share the root cause of today's warming - sudden increases in the amount of atmospheric carbon. Now, rapid is a relative term in geology. Something on the order of a thousand years is the blink of an eye gauged against geologic time. And both these events took centuries to unfold, and eons to reverse.

But when it comes to carbon emissions, humans are giving "rapid" a whole new meaning. For example, during the PETM warming, unusually intense and sustained volcanic activity was releasing about 0.2 of a gigatonne per year, whereas today, humans are releasing about 10 gigatonnes per year.

A recent report published in the prestigious Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, identifies ten feedbacks that could - and absent immediate action, likely will - increase the pace and extent of warming; something they refer to as the "Hothouse Earth" pathway. Hothouse Earth is not a planet compatible with the world humans evolved in, nor is it capable of sustaining civilization as we know it. For example, under the Hothouse Earth pathway, sea level would ultimately rise by as much as 60 meters (about 197 feet) and stay that way for millennia. This would inundate virtually every coastal city in the world, and displace close to 3 billion people. And these billions of refugees would come on top of others already displaced by heat, drought, disease, storms, hunger and the political unrest they would cause.

Feedbacks are the tail wagging the dog - together, they could dwarf the warming we're forecasting from just human emissions without feedbacks. Despite the fact that we've known about them for decades, they aren't considered by the IPCC forecasts, they're rarely covered in the news, they're routinely ignored in policy discussions, and we are dangerously close to triggering some of the worst of these feedbacks - if we haven't already.

Carbon budgets employ safety factors that aren't safe in order to give us the illusion that we have more time to act to avoid catastrophic warming. There's been a lot written about the Paris Agreement and why it may not have been adequate to stop dangerous warming, even before Trump withdrew the US and backtracked on Obama's carbon reduction measures. People pointed out that two degrees was too high to avoid feedbacks, that the measures were voluntary, that fully implemented it would still allow temperature increases of 3.5 degrees C or more. All legitimate, all deeply concerning. And the fact that countries are now behind in terms of meeting their targets shows these concerns were valid.

But the use of carbon budgets may be the least understood and most serious flaw in the Agreement - in fact, carbon budgets are the basis for all IPCC forecasts and they expose us to extraordinary risks.

We'll get to the details in a moment.

But first, a word about risk management. Typically, if the consequences of something are irreversible, ubiquitous, and catastrophic, we use extremely conservative safety factors when we design something. For example, airplanes and bridges are engineered with huge margins of safety and a lot of redundant systems. They are as close as we can come to fail-safe. But when it comes to protecting the Earth from the ravages of climate change, we're accepting risks of failure we wouldn't accept for a washing machine, a toaster or a blender.

When it comes to protecting the Earth from the ravages of climate change, we're accepting risks of failure we wouldn't accept for a washing machine, a toaster or a blender.

Now the details. Carbon budgets are established to determine the maximum amount of GHG we can emit, and for how long, to reach a given atmospheric level of GHG concentrations needed to limit warming to a given temperature increase. So, for example, if we seek to limit temperature increases to less than 2degC, then we have to limit GHG emissions to a level that avoids atmospheric concentrations sufficient to cause warming to exceed that limit.

In establishing carbon budgets, the IPCC used a series of probabilities for staying below the target temperature of 2 C (3.6 F). The probabilities they used were a 66 percent likelihood of meeting the target, a 50 percent likelihood of doing so, and a 30 percent likelihood. What this actually means is that 66 percent of the models forecast temperatures below the target level, or 50 percent of them do, or 30 percent of them do.

Notice what's not included in the carbon budgets the IPCC considered: a confidence level of 100 percent or even 90 percent. Now, think about this for a moment. We are using margins of safety for the future viability of our planet's life-support systems that we wouldn't tolerate in almost any other area of our life. Would you board a plane with a 33 percent chance of crashing? Cross a bridge that has only a 66 percent chance of holding up? No. You wouldn't.

So why is the 100 percent probability of making our goal not included in the IPCC's scenarios -- or the 90 percent probability for that matter? Answer: because we've already blown past the carbon emissions that would achieve either one. So now, we're stuck with the planetary equivalent of taking risks equal to playing Russian roulette with two bullets in the chamber. You'd think this would be a big deal, something worth talking about.

But of course, you'd be wrong.

By specifying a 66 percent probability of meeting the 2degC target, rather than 100 percent or 90 percent, we can appear to buy ourselves a lot of time. The lower we set the probability of staying below 2degC, the higher the allowable carbon budget and the more time we have to get off it. Of course, that doesn't actually give us more time--but it does provide the appearance of doing so.

So, higher odds of success require lower carbon budgets and give us less time, lower odds of success allow more carbon to be released over a longer time.

Now let's do some numbers.

If we wanted to have a 66 percent probability of staying below 1.5degC, our total carbon budget would be 2,250 tonnes of carbon dioxide. By the end of 2017, we burned through all but about 160 billion tonnes of that budget. Since we are emitting about forty billion tonnes per year (about forty-four billion US tons), we will blow through the budget in 2021. If we were to choose a more rational level of risk management, such as a 90 percent or 100 percent likelihood of preventing global Armageddon, we would have had to start acting a couple of decades ago, since we exceeded those limits in 2013.

Contrast this with the carbon budget based on a 66 percent probability of staying below 2degC, or 2,900 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide (GtCO2e). By 2017, we would appear to have nearly 810 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide emissions left, or twenty years' worth.

Playing craps with the planet we live on is--to say the least--irresponsible. Using an inadequate margin of safety doesn't actually increase the time we have to act to avoid catastrophic changes to our climate and seas, it merely appears to do so.

So the press ignores it; and we drift happily towards a rendezvous with an ecological Armageddon. But this is so inside baseball, that almost no one understands it except those making and using the carbon budgets. So the press ignores it; and we drift happily towards a rendezvous with an ecological Armageddon.

Avoiding doom and gloom when the news was gloomy. So why don't scientists sound the alarm about the full range of risk we're exposing ourselves and our children to? Well, as the NAS study shows, some are beginning to. James Hansen, Kevin Anderson, Michael Mann and several others have been trying to tell folks the dire consequences of climate change for some time now.

But in general, scientists and journalists have avoided spreading "doom and gloom," preferring to sound a more hopeful and optimistic tone.

As I noted last year, when David Wallace Wells wrote The Uninhabitable Earth - a truly worst case summary of what our world was becoming -- he was roundly criticized by scientists for spreading doom and gloom. Aside from one error about the magnitude of warming that melting perma-frost might cause, Wallace-Wells article used plausible worst-case forecasts to paint the picture of the world we are heading toward. And as the Scientific American noted, when you ground-truth past forecasts against what actually happened, the best fit comes from using worst-case or even worse than worst-case forecasts, so he was on sound ground.

Yet such was the blow back that Wallace-Wells has been taking a much softer and more optimistic tone lately.

I call Bullshit on the anti-doom and gloomers. Again, standard risk management strategies suggest we use the utmost caution - which is to say, assume the worst, and spare no expense in adopting policies which will prevent an outcome that is potentially ubiquitous, cataclysmic and irreversible. Nothing, with the possible exception of an all-out nuclear war, fits that category better than climate change.

But because of what James Hansen calls scientific reticence, scientists have been reluctant to raise alarms, and when they have, many were not particularly good at it, couching there concerns in the careful language of science.

As a result, people don't fully understand the true nature of the threat that climate change poses, and the press - when they bother to cover it - understates it.

Neoclassical economics provides a convenient excuse for inaction. Ever since Hansen delivered his testimony before the Senate on the threat of climate change in 1988, economists and deniers using economic arguments, have been telling us that taking action to prevent climate change is too expensive. This was never a credible argument, given that what was at stake were trillions of dollars of real estate, hundreds of millions dead, loss of priceless habitat, mass extinctions, epidemics, unprecedented drought, spreading pestilence and widespread famine. But the conventions of economics - especially the practice of discounting future benefits - grossly undervalues the benefits to future generations from present expenditures. That is, economic analyses tend to conclude that money spent today to protect future generations is rarely worth it.

Discounting in economics has been the stuff of PhD Thesis and Nobel Prizes, but David Roberts has written an accessible explanation of why it's important and how profoundly it can distort policy in an article entitled, "Discount Rates: A boring thing you should know about, (with otters!)."

There are other problems with economics - it presumes everyone is behaving rationally, then measures "rational" as maximizing their returns and these returns are measured in currency. As psychologist Daniel Kahneman and others have proved, humans simply aren't all that rational when it comes to real world economic behavior, and they measure returns in all kinds of ways. In fact, Kahneman won the Nobel prize in economics for his work showing the fallacy of the perfectly rational agent.

Economists chose to make simplifying assumptions about human rationality so that they could create elegant and often quite complex mathematical models about how the economy works - something another Nobel prize winning economist, Paul Krugman, called mistaking beauty for truth.

It never made sense to argue that tackling climate change would impose a net cost on society to avoid the most expensive catastrophe in human history, but now that renewables are the cheapest source of power, arguing against climate mitigation and propping up fossil fuel investments hurts the economy and costs us jobs today - right now.

If past is prologue, the media will soon move on, leaving the greatest threat humanity has ever faced virtually uncovered. As the flood waters recede, and the smoke covering the western United States dissipates, what little coverage climate change gets in the media will slow to a trickle. It's hard to compete with Trump's daily outrages, or the Republican Congress's epic hypocrisy. And make no mistake, they pose a clear and present danger to the institutions that sustain what's left of our democracy. And the Democrats' internal battle for identity - a fight between progressive values and the same old money ball politics - is endlessly fascinating.

But the consequences of the inside-the-beltway political games, interesting as they are, pale in comparison to the consequences of ignoring or underestimating the consequences of climate change. An ecologically viable planet capable of sustaining civilization is, after all, a prerequisite to all the other games humans play.

Climate change catastrophe is upon us. We see it in the record-breaking floods from storms like Florence, and in the record-breaking fires across the US once again this year. But the media - which barely mentioned the link between these catastrophes and climate change -- is preparing to move on to the next new, new, thing. Can't blame them. Trump and the Republicans are providing enough fodder to feed a thousand news cycles with daily outrages that keep the country on the edge of chaos.

But here's the thing - climate change will affect us more profoundly, more negatively, and sooner than anything we've been led to believe. What we're seeing now is just a taste of what the future holds, and the disasters we're causing today with our continued use of fossil fuels will soon be a permanent feature of our existence, irrevocable in anything other than geologic time, if we don't act immediately.

What we're seeing now is just a taste of what the future holds, and the disasters we're causing today with our continued use of fossil fuels will soon be a permanent feature of our existence, irrevocable in anything other than geologic time, if we don't act immediately.

Here's why.

We're ignoring feedbacks in our forecasts. Back in 2004, in an article in the Baltimore Sun, I warned that the rapid warming in the Arctic had the potential to release methane from clathrates and permafrost, speeding up the rate and extent of warming. By 2006, I noted that there was evidence that this particular feedback had started already.

It's been known for some time that feedbacks cause earth systems to respond non-linearly - that is to experience extreme and swift reactions well beyond what our models forecast. Such rapid warming can be found throughout the geologic record, and two of the most disruptive, the Permian die-off and the Paleocene/Eocene thermal Maximum (PETM), share the root cause of today's warming - sudden increases in the amount of atmospheric carbon. Now, rapid is a relative term in geology. Something on the order of a thousand years is the blink of an eye gauged against geologic time. And both these events took centuries to unfold, and eons to reverse.

But when it comes to carbon emissions, humans are giving "rapid" a whole new meaning. For example, during the PETM warming, unusually intense and sustained volcanic activity was releasing about 0.2 of a gigatonne per year, whereas today, humans are releasing about 10 gigatonnes per year.

A recent report published in the prestigious Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, identifies ten feedbacks that could - and absent immediate action, likely will - increase the pace and extent of warming; something they refer to as the "Hothouse Earth" pathway. Hothouse Earth is not a planet compatible with the world humans evolved in, nor is it capable of sustaining civilization as we know it. For example, under the Hothouse Earth pathway, sea level would ultimately rise by as much as 60 meters (about 197 feet) and stay that way for millennia. This would inundate virtually every coastal city in the world, and displace close to 3 billion people. And these billions of refugees would come on top of others already displaced by heat, drought, disease, storms, hunger and the political unrest they would cause.

Feedbacks are the tail wagging the dog - together, they could dwarf the warming we're forecasting from just human emissions without feedbacks. Despite the fact that we've known about them for decades, they aren't considered by the IPCC forecasts, they're rarely covered in the news, they're routinely ignored in policy discussions, and we are dangerously close to triggering some of the worst of these feedbacks - if we haven't already.

Carbon budgets employ safety factors that aren't safe in order to give us the illusion that we have more time to act to avoid catastrophic warming. There's been a lot written about the Paris Agreement and why it may not have been adequate to stop dangerous warming, even before Trump withdrew the US and backtracked on Obama's carbon reduction measures. People pointed out that two degrees was too high to avoid feedbacks, that the measures were voluntary, that fully implemented it would still allow temperature increases of 3.5 degrees C or more. All legitimate, all deeply concerning. And the fact that countries are now behind in terms of meeting their targets shows these concerns were valid.

But the use of carbon budgets may be the least understood and most serious flaw in the Agreement - in fact, carbon budgets are the basis for all IPCC forecasts and they expose us to extraordinary risks.

We'll get to the details in a moment.

But first, a word about risk management. Typically, if the consequences of something are irreversible, ubiquitous, and catastrophic, we use extremely conservative safety factors when we design something. For example, airplanes and bridges are engineered with huge margins of safety and a lot of redundant systems. They are as close as we can come to fail-safe. But when it comes to protecting the Earth from the ravages of climate change, we're accepting risks of failure we wouldn't accept for a washing machine, a toaster or a blender.

When it comes to protecting the Earth from the ravages of climate change, we're accepting risks of failure we wouldn't accept for a washing machine, a toaster or a blender.

Now the details. Carbon budgets are established to determine the maximum amount of GHG we can emit, and for how long, to reach a given atmospheric level of GHG concentrations needed to limit warming to a given temperature increase. So, for example, if we seek to limit temperature increases to less than 2degC, then we have to limit GHG emissions to a level that avoids atmospheric concentrations sufficient to cause warming to exceed that limit.

In establishing carbon budgets, the IPCC used a series of probabilities for staying below the target temperature of 2 C (3.6 F). The probabilities they used were a 66 percent likelihood of meeting the target, a 50 percent likelihood of doing so, and a 30 percent likelihood. What this actually means is that 66 percent of the models forecast temperatures below the target level, or 50 percent of them do, or 30 percent of them do.

Notice what's not included in the carbon budgets the IPCC considered: a confidence level of 100 percent or even 90 percent. Now, think about this for a moment. We are using margins of safety for the future viability of our planet's life-support systems that we wouldn't tolerate in almost any other area of our life. Would you board a plane with a 33 percent chance of crashing? Cross a bridge that has only a 66 percent chance of holding up? No. You wouldn't.

So why is the 100 percent probability of making our goal not included in the IPCC's scenarios -- or the 90 percent probability for that matter? Answer: because we've already blown past the carbon emissions that would achieve either one. So now, we're stuck with the planetary equivalent of taking risks equal to playing Russian roulette with two bullets in the chamber. You'd think this would be a big deal, something worth talking about.

But of course, you'd be wrong.

By specifying a 66 percent probability of meeting the 2degC target, rather than 100 percent or 90 percent, we can appear to buy ourselves a lot of time. The lower we set the probability of staying below 2degC, the higher the allowable carbon budget and the more time we have to get off it. Of course, that doesn't actually give us more time--but it does provide the appearance of doing so.

So, higher odds of success require lower carbon budgets and give us less time, lower odds of success allow more carbon to be released over a longer time.

Now let's do some numbers.

If we wanted to have a 66 percent probability of staying below 1.5degC, our total carbon budget would be 2,250 tonnes of carbon dioxide. By the end of 2017, we burned through all but about 160 billion tonnes of that budget. Since we are emitting about forty billion tonnes per year (about forty-four billion US tons), we will blow through the budget in 2021. If we were to choose a more rational level of risk management, such as a 90 percent or 100 percent likelihood of preventing global Armageddon, we would have had to start acting a couple of decades ago, since we exceeded those limits in 2013.

Contrast this with the carbon budget based on a 66 percent probability of staying below 2degC, or 2,900 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide (GtCO2e). By 2017, we would appear to have nearly 810 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide emissions left, or twenty years' worth.

Playing craps with the planet we live on is--to say the least--irresponsible. Using an inadequate margin of safety doesn't actually increase the time we have to act to avoid catastrophic changes to our climate and seas, it merely appears to do so.

So the press ignores it; and we drift happily towards a rendezvous with an ecological Armageddon. But this is so inside baseball, that almost no one understands it except those making and using the carbon budgets. So the press ignores it; and we drift happily towards a rendezvous with an ecological Armageddon.

Avoiding doom and gloom when the news was gloomy. So why don't scientists sound the alarm about the full range of risk we're exposing ourselves and our children to? Well, as the NAS study shows, some are beginning to. James Hansen, Kevin Anderson, Michael Mann and several others have been trying to tell folks the dire consequences of climate change for some time now.

But in general, scientists and journalists have avoided spreading "doom and gloom," preferring to sound a more hopeful and optimistic tone.

As I noted last year, when David Wallace Wells wrote The Uninhabitable Earth - a truly worst case summary of what our world was becoming -- he was roundly criticized by scientists for spreading doom and gloom. Aside from one error about the magnitude of warming that melting perma-frost might cause, Wallace-Wells article used plausible worst-case forecasts to paint the picture of the world we are heading toward. And as the Scientific American noted, when you ground-truth past forecasts against what actually happened, the best fit comes from using worst-case or even worse than worst-case forecasts, so he was on sound ground.

Yet such was the blow back that Wallace-Wells has been taking a much softer and more optimistic tone lately.

I call Bullshit on the anti-doom and gloomers. Again, standard risk management strategies suggest we use the utmost caution - which is to say, assume the worst, and spare no expense in adopting policies which will prevent an outcome that is potentially ubiquitous, cataclysmic and irreversible. Nothing, with the possible exception of an all-out nuclear war, fits that category better than climate change.

But because of what James Hansen calls scientific reticence, scientists have been reluctant to raise alarms, and when they have, many were not particularly good at it, couching there concerns in the careful language of science.

As a result, people don't fully understand the true nature of the threat that climate change poses, and the press - when they bother to cover it - understates it.

Neoclassical economics provides a convenient excuse for inaction. Ever since Hansen delivered his testimony before the Senate on the threat of climate change in 1988, economists and deniers using economic arguments, have been telling us that taking action to prevent climate change is too expensive. This was never a credible argument, given that what was at stake were trillions of dollars of real estate, hundreds of millions dead, loss of priceless habitat, mass extinctions, epidemics, unprecedented drought, spreading pestilence and widespread famine. But the conventions of economics - especially the practice of discounting future benefits - grossly undervalues the benefits to future generations from present expenditures. That is, economic analyses tend to conclude that money spent today to protect future generations is rarely worth it.

Discounting in economics has been the stuff of PhD Thesis and Nobel Prizes, but David Roberts has written an accessible explanation of why it's important and how profoundly it can distort policy in an article entitled, "Discount Rates: A boring thing you should know about, (with otters!)."

There are other problems with economics - it presumes everyone is behaving rationally, then measures "rational" as maximizing their returns and these returns are measured in currency. As psychologist Daniel Kahneman and others have proved, humans simply aren't all that rational when it comes to real world economic behavior, and they measure returns in all kinds of ways. In fact, Kahneman won the Nobel prize in economics for his work showing the fallacy of the perfectly rational agent.

Economists chose to make simplifying assumptions about human rationality so that they could create elegant and often quite complex mathematical models about how the economy works - something another Nobel prize winning economist, Paul Krugman, called mistaking beauty for truth.

It never made sense to argue that tackling climate change would impose a net cost on society to avoid the most expensive catastrophe in human history, but now that renewables are the cheapest source of power, arguing against climate mitigation and propping up fossil fuel investments hurts the economy and costs us jobs today - right now.

If past is prologue, the media will soon move on, leaving the greatest threat humanity has ever faced virtually uncovered. As the flood waters recede, and the smoke covering the western United States dissipates, what little coverage climate change gets in the media will slow to a trickle. It's hard to compete with Trump's daily outrages, or the Republican Congress's epic hypocrisy. And make no mistake, they pose a clear and present danger to the institutions that sustain what's left of our democracy. And the Democrats' internal battle for identity - a fight between progressive values and the same old money ball politics - is endlessly fascinating.

But the consequences of the inside-the-beltway political games, interesting as they are, pale in comparison to the consequences of ignoring or underestimating the consequences of climate change. An ecologically viable planet capable of sustaining civilization is, after all, a prerequisite to all the other games humans play.