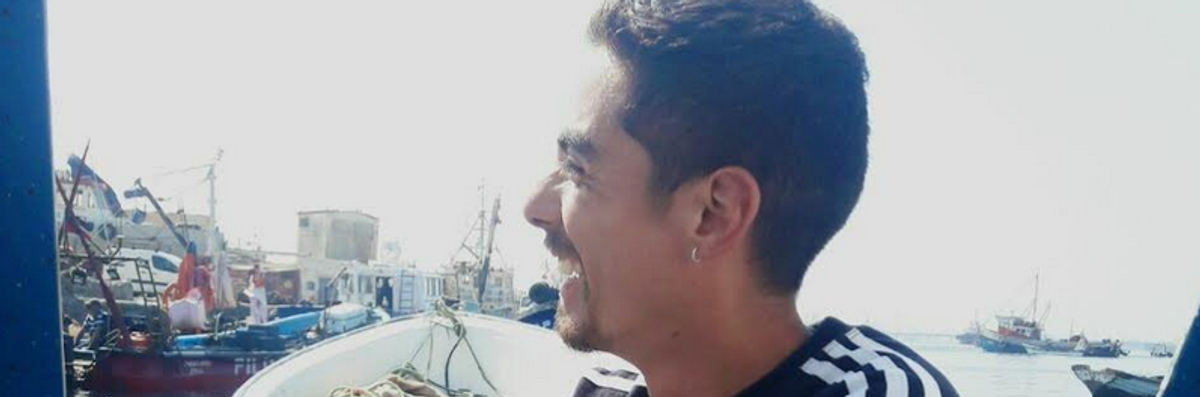

Alejandro Castro, a fisherman and union leader, was fighting local pollution before his death. (Photo: via Facebook)

Chilean Union Leader Found Dead One Day After Anti-Pollution Demo

One day after protesting massive chemical pollution, Alejandro Castro was found, hanging. The artisanal fisherman union leader had just pulled off a mass mobilization against acute chemical intoxication. Defending a community against polluters is an increasingly dangerous activity. The number of environmentalists killed is up from one a week just a decade ago to four a week nowadays.

The Chilean government calls it suicide, but girlfriend Pollet Urrutia said: "he was not in a state of mind for that. He was willing to keep up the fight and had many plans." Alejandro's death is under investigation. The police says he received death threats. Congressman Latorre called for the revision of the cameras located where Alejandro was found. Alejandro's case comes in the wake of the Maracena Valdez case, who was found dead in 2016 and the Mapuche leader Nicolasa Quitreman, who was found dead in 2013. While first labelled as suicides, a police investigation later recognized that Macarena's dead was not a suicide.

Sacrifice zones

The area of the incident is Puchuncavi-Quintero, but the region is better known as one of Chile's four "sacrifice zones." It earned this dubious title because several industries have been operating without public monitoring since 1964, dumping different types of toxic chemicals in unknown quantities. The term is used by socio-ecological movements in Chile to characterize geographical areas where industry and waste are so heavy that the whole area and the people living in it are considered sacrificed on the altar of economic growth. But those people are increasingly well informed and actively resisting the scandalous situation. As schools closed and social actions increased, the so-called special forces and the navy deployed an unusual amount of force, with water cannons, rubber bullets and tear gas. Quintero has turned into a battle zone.

As of today, there are at least 12 high-impact industries operating in the Puchuncavi zone in an area of 8.5 square km, including oil refining, chemical processing, thermoelectric industry and a copper processing plant. According to the Chilean legislation, an area can be called saturated due to the pollutant's concentration. But environmental legislation does not prohibit installation of new facilities and a cleaning plan can take up to nine years before it becomes a reality. Two researchers, Bolados and Sanchez, studied the Puchuncavi zone and wrote that "At the end of the 1980s, pioneering studies indicated that the toxic agents in the Puchuncavi air posed risks for the quality of life ... that led, in 1993, to declare Puchuncavi as a Saturated Zone for particulate matter (PM) and sulphur dioxide (SO2)", adding this is "a condition that continues to this day."

The Chilean Medical Union Association recently requested the government to declare a health emergency in the area. Today there are more than a thousand people intoxicated by local pollutants, including two police experts who were conducting research in the area. President Pinera's administration announced cosmetic measures. However, up to today, the acute intoxication continues. Maybe Alejandro's dead at a time of tensions will change the equation. Special police forces seized the offices of some companies, including state-owned oil refinery company ENAP. However, this in turn led to protests from the ENAP unions who want to keep the refinery open.

Chile's downgrading of protection for the protectors

Pinera's administration recently dropped out of the Escazu agreement, which seeks to improve environmental governance through access to information, participation and environmental justice. This agreement was initially proposed by Chile, among other countries, and is now sponsored by the United Nations, through ECLAC, in line with the 10th principle of the Rio Declaration. The Escazu Agreement, among others, protects environmental activists.

Alejandro's death is another grim reminder of the urgent need to protect the protectors. Today, four people protecting the planet are killed each week - up from only one a week ten years ago. An economic system that sacrifices whole zones on the altar of growth will continue to contaminate, displace and kill ever more people, animals and plants. But from the mines to the landfills and from the harbours to the farms: across the globe peoples are fighting back to save their community.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

One day after protesting massive chemical pollution, Alejandro Castro was found, hanging. The artisanal fisherman union leader had just pulled off a mass mobilization against acute chemical intoxication. Defending a community against polluters is an increasingly dangerous activity. The number of environmentalists killed is up from one a week just a decade ago to four a week nowadays.

The Chilean government calls it suicide, but girlfriend Pollet Urrutia said: "he was not in a state of mind for that. He was willing to keep up the fight and had many plans." Alejandro's death is under investigation. The police says he received death threats. Congressman Latorre called for the revision of the cameras located where Alejandro was found. Alejandro's case comes in the wake of the Maracena Valdez case, who was found dead in 2016 and the Mapuche leader Nicolasa Quitreman, who was found dead in 2013. While first labelled as suicides, a police investigation later recognized that Macarena's dead was not a suicide.

Sacrifice zones

The area of the incident is Puchuncavi-Quintero, but the region is better known as one of Chile's four "sacrifice zones." It earned this dubious title because several industries have been operating without public monitoring since 1964, dumping different types of toxic chemicals in unknown quantities. The term is used by socio-ecological movements in Chile to characterize geographical areas where industry and waste are so heavy that the whole area and the people living in it are considered sacrificed on the altar of economic growth. But those people are increasingly well informed and actively resisting the scandalous situation. As schools closed and social actions increased, the so-called special forces and the navy deployed an unusual amount of force, with water cannons, rubber bullets and tear gas. Quintero has turned into a battle zone.

As of today, there are at least 12 high-impact industries operating in the Puchuncavi zone in an area of 8.5 square km, including oil refining, chemical processing, thermoelectric industry and a copper processing plant. According to the Chilean legislation, an area can be called saturated due to the pollutant's concentration. But environmental legislation does not prohibit installation of new facilities and a cleaning plan can take up to nine years before it becomes a reality. Two researchers, Bolados and Sanchez, studied the Puchuncavi zone and wrote that "At the end of the 1980s, pioneering studies indicated that the toxic agents in the Puchuncavi air posed risks for the quality of life ... that led, in 1993, to declare Puchuncavi as a Saturated Zone for particulate matter (PM) and sulphur dioxide (SO2)", adding this is "a condition that continues to this day."

The Chilean Medical Union Association recently requested the government to declare a health emergency in the area. Today there are more than a thousand people intoxicated by local pollutants, including two police experts who were conducting research in the area. President Pinera's administration announced cosmetic measures. However, up to today, the acute intoxication continues. Maybe Alejandro's dead at a time of tensions will change the equation. Special police forces seized the offices of some companies, including state-owned oil refinery company ENAP. However, this in turn led to protests from the ENAP unions who want to keep the refinery open.

Chile's downgrading of protection for the protectors

Pinera's administration recently dropped out of the Escazu agreement, which seeks to improve environmental governance through access to information, participation and environmental justice. This agreement was initially proposed by Chile, among other countries, and is now sponsored by the United Nations, through ECLAC, in line with the 10th principle of the Rio Declaration. The Escazu Agreement, among others, protects environmental activists.

Alejandro's death is another grim reminder of the urgent need to protect the protectors. Today, four people protecting the planet are killed each week - up from only one a week ten years ago. An economic system that sacrifices whole zones on the altar of growth will continue to contaminate, displace and kill ever more people, animals and plants. But from the mines to the landfills and from the harbours to the farms: across the globe peoples are fighting back to save their community.

One day after protesting massive chemical pollution, Alejandro Castro was found, hanging. The artisanal fisherman union leader had just pulled off a mass mobilization against acute chemical intoxication. Defending a community against polluters is an increasingly dangerous activity. The number of environmentalists killed is up from one a week just a decade ago to four a week nowadays.

The Chilean government calls it suicide, but girlfriend Pollet Urrutia said: "he was not in a state of mind for that. He was willing to keep up the fight and had many plans." Alejandro's death is under investigation. The police says he received death threats. Congressman Latorre called for the revision of the cameras located where Alejandro was found. Alejandro's case comes in the wake of the Maracena Valdez case, who was found dead in 2016 and the Mapuche leader Nicolasa Quitreman, who was found dead in 2013. While first labelled as suicides, a police investigation later recognized that Macarena's dead was not a suicide.

Sacrifice zones

The area of the incident is Puchuncavi-Quintero, but the region is better known as one of Chile's four "sacrifice zones." It earned this dubious title because several industries have been operating without public monitoring since 1964, dumping different types of toxic chemicals in unknown quantities. The term is used by socio-ecological movements in Chile to characterize geographical areas where industry and waste are so heavy that the whole area and the people living in it are considered sacrificed on the altar of economic growth. But those people are increasingly well informed and actively resisting the scandalous situation. As schools closed and social actions increased, the so-called special forces and the navy deployed an unusual amount of force, with water cannons, rubber bullets and tear gas. Quintero has turned into a battle zone.

As of today, there are at least 12 high-impact industries operating in the Puchuncavi zone in an area of 8.5 square km, including oil refining, chemical processing, thermoelectric industry and a copper processing plant. According to the Chilean legislation, an area can be called saturated due to the pollutant's concentration. But environmental legislation does not prohibit installation of new facilities and a cleaning plan can take up to nine years before it becomes a reality. Two researchers, Bolados and Sanchez, studied the Puchuncavi zone and wrote that "At the end of the 1980s, pioneering studies indicated that the toxic agents in the Puchuncavi air posed risks for the quality of life ... that led, in 1993, to declare Puchuncavi as a Saturated Zone for particulate matter (PM) and sulphur dioxide (SO2)", adding this is "a condition that continues to this day."

The Chilean Medical Union Association recently requested the government to declare a health emergency in the area. Today there are more than a thousand people intoxicated by local pollutants, including two police experts who were conducting research in the area. President Pinera's administration announced cosmetic measures. However, up to today, the acute intoxication continues. Maybe Alejandro's dead at a time of tensions will change the equation. Special police forces seized the offices of some companies, including state-owned oil refinery company ENAP. However, this in turn led to protests from the ENAP unions who want to keep the refinery open.

Chile's downgrading of protection for the protectors

Pinera's administration recently dropped out of the Escazu agreement, which seeks to improve environmental governance through access to information, participation and environmental justice. This agreement was initially proposed by Chile, among other countries, and is now sponsored by the United Nations, through ECLAC, in line with the 10th principle of the Rio Declaration. The Escazu Agreement, among others, protects environmental activists.

Alejandro's death is another grim reminder of the urgent need to protect the protectors. Today, four people protecting the planet are killed each week - up from only one a week ten years ago. An economic system that sacrifices whole zones on the altar of growth will continue to contaminate, displace and kill ever more people, animals and plants. But from the mines to the landfills and from the harbours to the farms: across the globe peoples are fighting back to save their community.