New research suggests temperature and sea level rise could be far worse than climate models predict. (Photo: Christopher Michel/Flickr/cc)

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

New research suggests temperature and sea level rise could be far worse than climate models predict. (Photo: Christopher Michel/Flickr/cc)

Since the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released its new, must-read report on the urgency of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, we at Oil Change International have been receiving some common questions: What are the implications for our analysis of what the Paris accord's goals mean for fossil fuel production? What about the IPCC's use of larger carbon budgets, compared to its last major report? What, if any, new conclusions do we draw?

The quick summary is this: It's clear that the IPCC's 1.5-degree report clarifies and adds urgency to our call for a managed decline of fossil fuel production. Winding down the largest source of carbon emissions--the oil, gas, and coal extracted by the fossil fuel industry--will be essential to achieving deep cuts in carbon emissions within the next decade, as the report warns is necessary. In this post, I'll unpack three key takeaways:

(Questions such as, Is there hope? (yes), and, Is this possible? (yes), are also critical parts of the discussion right now. I focus here the technical aspects related to our analysis.)

First, a bit of background: We at Oil Change International (OCI) first analyzed the limits that the Paris goals imply for fossil fuel production in 2016, and the results were sobering. In our report, The Sky's Limit: Why the Paris Goals Require a Managed Decline of Fossil Fuel Production, we found that the oil, gas, and coal in existing fields and mines globally contain enough potential carbon emissions to push the world beyond the Paris climate goals.

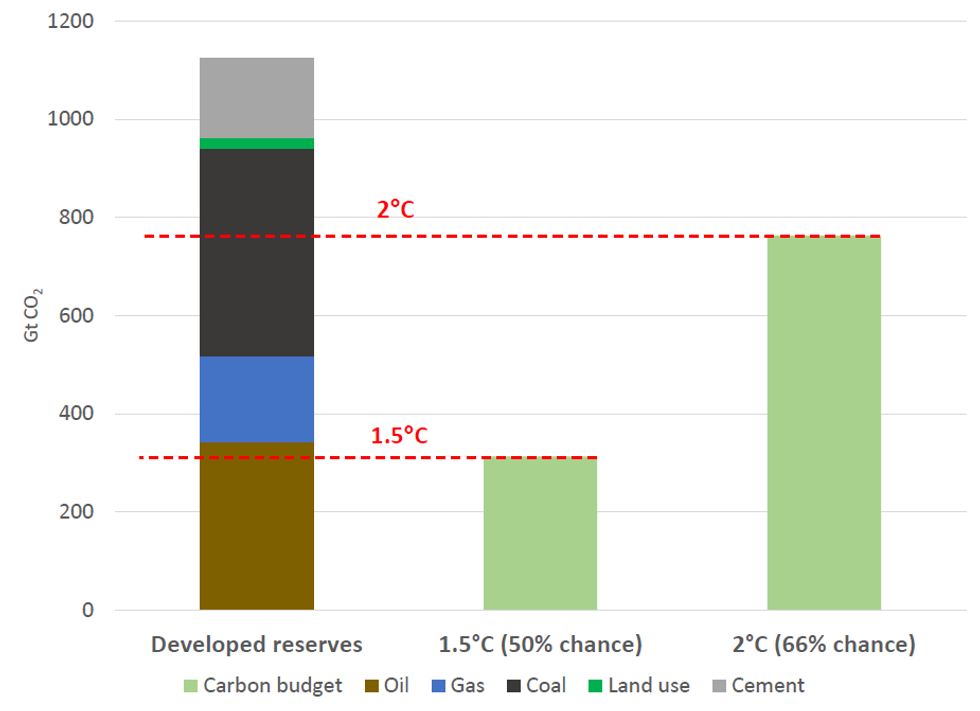

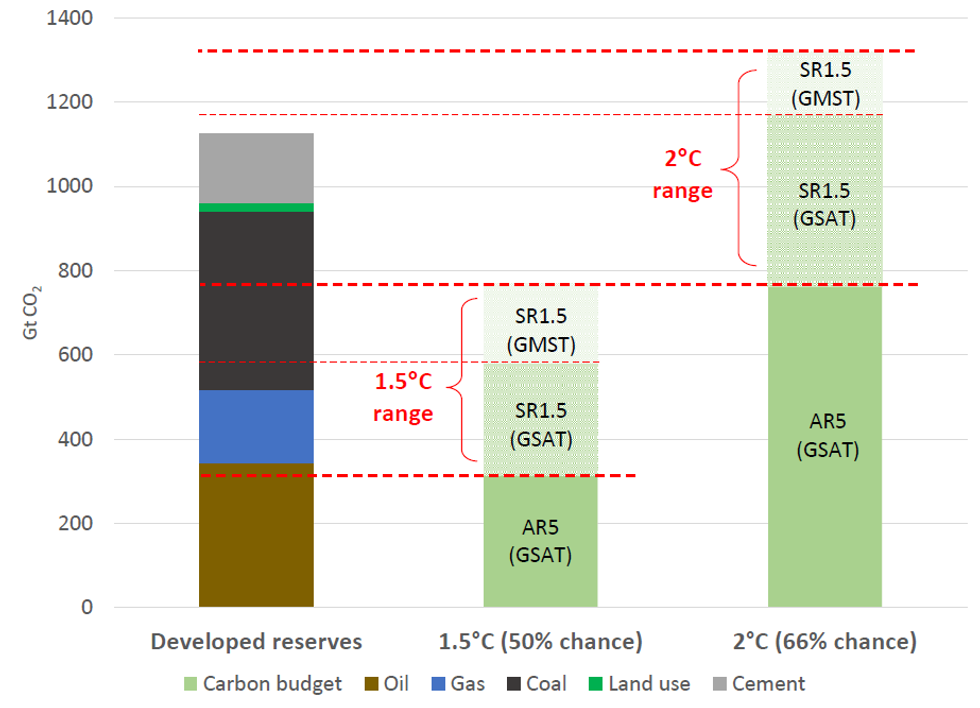

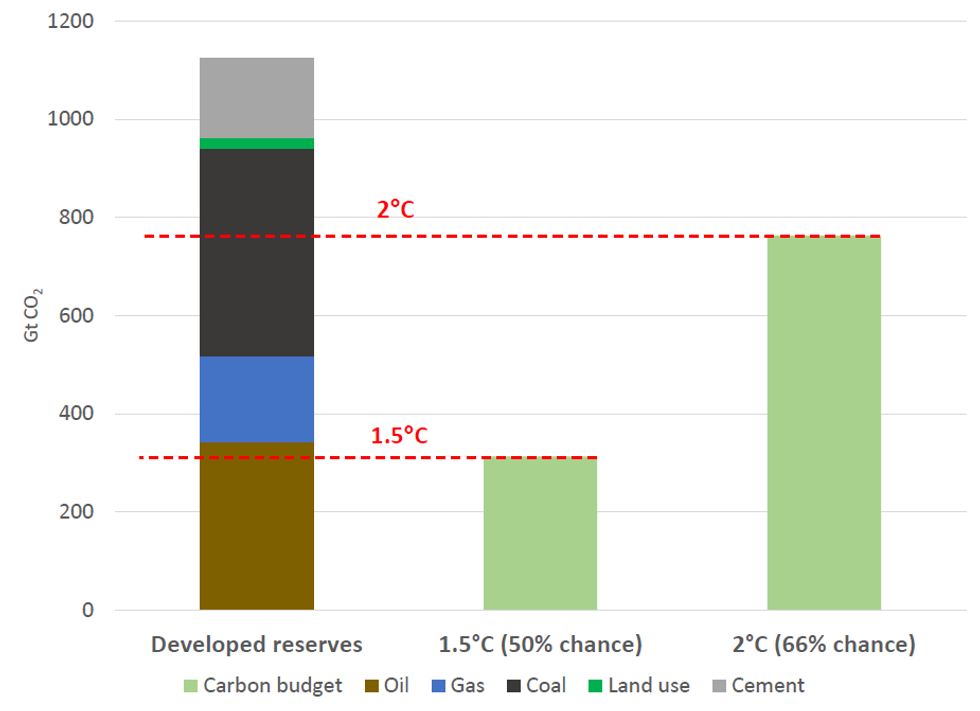

We arrived at this result by using carbon budgets from the IPCC's 5th Assessment Synthesis Report, which reflected the scientific consensus at the time. We took budgets that were consistent with the range of the Paris goals--aiming to limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (degC) or "well below" 2degC. We then compared those budgets to the potential cumulative carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from already-developed fossil fuel reserves globally. You can see the results in the figure below.

Developed Fossil Fuel Reserves, Compared to Carbon Budgets in the IPCC 5th Assessment Report [1]

We drew two primary conclusions from these results:

These recommendations were informed by our understanding of the dynamics of carbon lock-in. Developed reserves represent the oil, gas, and coal that the fossil fuel industry has already invested in extracting--the capital is sunk, the wells have been (or are being) drilled, the pits dug, and the related infrastructure constructed. Once a project is operating, there are economic, political, and legal factors that push for continued operation and present barriers to early closure.

Given the hard limit to how much fossil fuel can be extracted, and given the inertia behind existing projects, continuing to expand the footprint of the fossil fuel industry now risks two potentially overlapping outcomes: 1) Climate chaos, as the industry locks in levels of emissions that far exceed the Paris limits; and/or; 2) Economic chaos, from a sudden scramble to end fossil fuel production and use at a later date.

How has the new IPCC report adjusted our thinking?

The most important way the new IPCC has changed our thinking is that it has persuaded us that we need to aim to limit warming to 1.5 degrees, not just "well below 2 degrees." It's important to remember that 1.5degC exists as a goal within the Paris accord because some of the world's most climate-vulnerable nations demanded it, asserting this level of ambition as essential to their survival. The IPCC report provides powerful scientific backing for their call.

The report finds that exceeding 1.5degC of warming and hitting the 2degC threshold would put millions more people at risk of death, poverty, water and food shortages, and displacement from rising sea levels, while increasing the odds of irreversible, runaway ruptures in our climate system. We can significantly lessen the loss of human lives, whole communities, and ecosystems if governments interpret the upper limit of the Paris agreement--of keeping warming "well below" 2degC--to mean limiting it to 1.5degC.

Accordingly, we at OCI are shifting how we emphasize these goals in our own analysis, referring to 1.5degC first and as the primary aim when we discuss the Paris goals. We expect the IPCC report will encourage some governments and others to do the same.

One element of the new IPCC report has sparked questions and some confusion: the shifting size of the carbon budgets. As a basic concept, carbon budgets are relatively simple. They indicate how much CO2 can be emitted before the world reaches a certain temperature threshold. But calculating them depends on a variety of factors: how you measure the level of warming to date, how you measure temperatures (i.e., by air, sea, or a combination), how you define a "pre-industrial" baseline for human-caused emissions, exactly how many emissions have occurred since then, and how other greenhouse gas emissions influence the climate.

Since the IPCC's 5th Assessment Report, released in 2014, scientists have continued to examine the assumptions and methods that go into calculating carbon budgets. A much-debated paper released last year by Millar et al. (see our commentary on it here) proposed a new methodology, shifting the reference period from which models calculate carbon budgets to the recent past rather than pre-industrial times. Since the new reference period experienced slightly less warming than indicated by the models, the new methodology concluded that remaining carbon budgets for the 1.5degC and 2degC temperature thresholds may be larger as a result. The IPCC's 1.5-degree report adopted this new methodology, estimating that carbon budgets are roughly 300 gigatonnes (Gt) larger compared to those published in the 5th Assessment Report,[2] while noting that significant uncertainty remains around the size of this adjustment.

This is an active, ongoing scientific debate (for instructive overviews, read briefs from Climate Analytics and Carbon Brief). As such, it's not yet clear if the larger carbon budgets in the latest IPCC report fully reflect a new scientific consensus. In fact, it's so unsettled that the IPCC report gives two sets of budgets for each ambition level, based on different observational datasets. Some scientists have already said the report is too conservative, overstating remaining carbon budgets (in both versions) and understating risks. It's perhaps a case of unfortunate timing for the IPCC report, as it had to be written while that debate was just getting started.

Rather than waiting for a new consensus to be settled, let's take a look at what these larger budgets would mean if they're right. If we have a bit more space in global carbon budgets than previously thought, that's clearly a good thing. It would increase our chances of limiting catastrophic climate changes. Does this also imply there is some room to expand fossil fuel production?

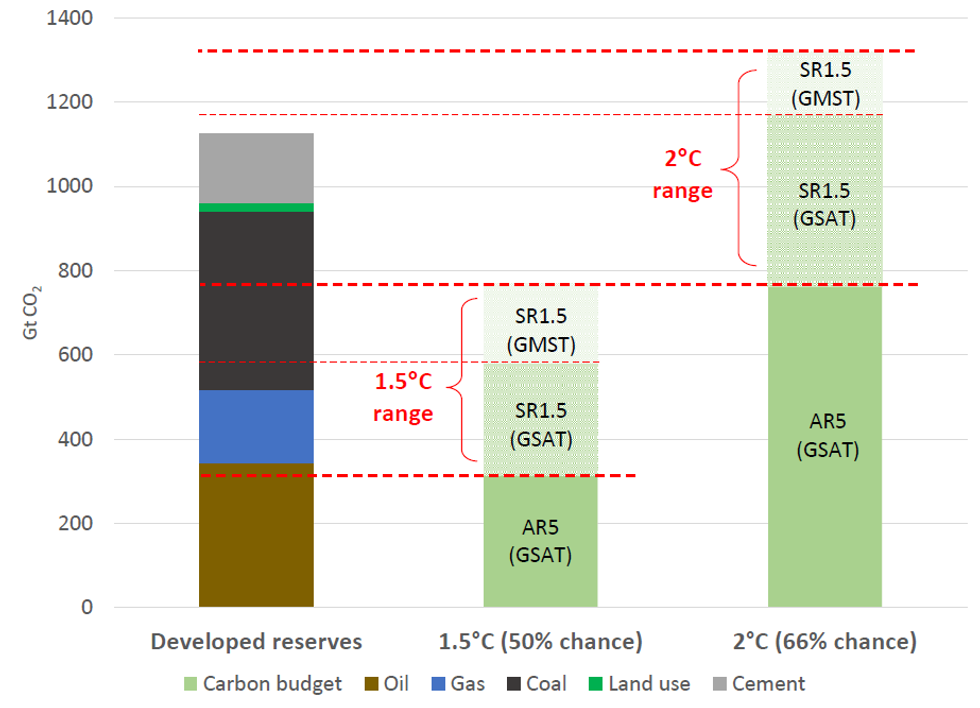

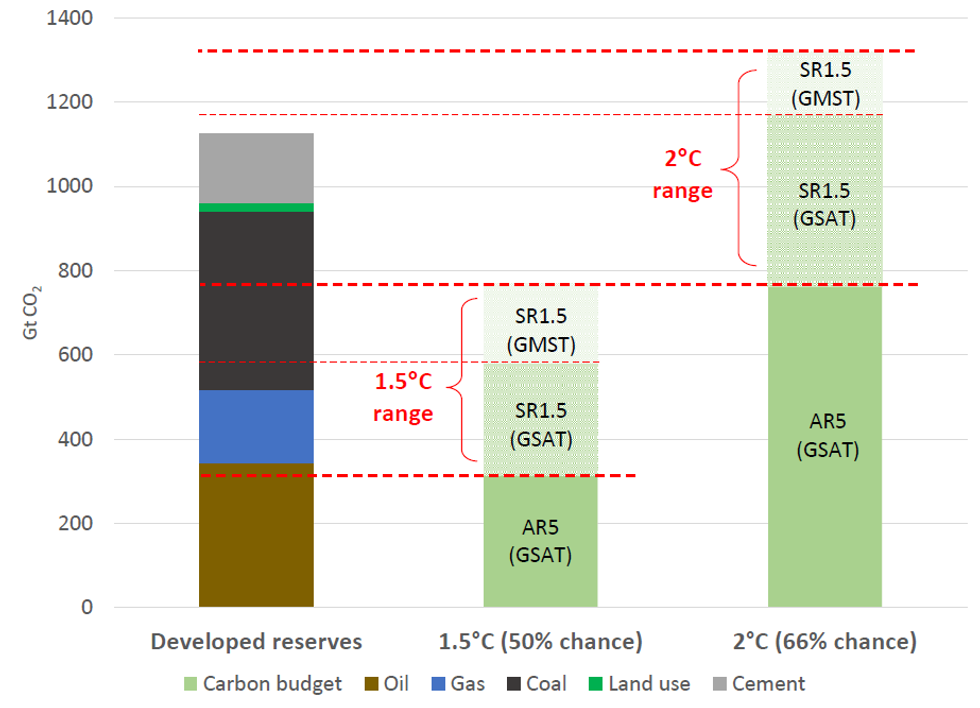

The figure below shows how our original Sky's Limit calculation of developed fossil fuel reserves compares to the larger carbon budget sizes in the latest IPCC report (using the same 50 and 66 percent probability levels for 1.5degC and 2degC respectively). The bottom, darkest portions of the carbon budget bars show the budgets from the 5th Assessment Report (AR5), updated to reflect CO2 emissions through the end of 2017. The middle-shaded portions reflect the larger carbon budgets from the Special Report on 1.5 degrees (SR1.5) that use the same measure of warming as the 5th Assessment Report--global surface air temperature (GSAT). The top-shaded regions show the larger budgets based on a different temperature measure--global mean surface temperature (GMST), the average of air and sea surface temperatures.

For context, observational datasets generally use GMST, which is why the Millar et al. paper, based on observed warming to date, used them. On the other hand, the AR5, the scientific basis on which the Paris Agreement was reached, relied on GSAT. (For the sake of brevity, this is a simplification of the underlying science.) For assessing the Paris goals, one could argue against shifting goalposts. We look at both sets, since they both appear in the SR1.5.

Developed Fossil Fuel Reserves, Compared to Updated IPCC Carbon Budgets (GSAT and GMST) [3]

In each of these cases, developed reserves still significantly exceed the carbon budgets for a one-in-two chance of limiting warming to 1.5degC. Developed reserves are double the carbon budget for 1.5degC that's based on GSAT, after adding in optimistic estimates of future land use and cement manufacture emissions (which are more difficult to reduce than energy sector emissions).

With the larger budgets, there is some space between estimated emissions and the carbon budget limits for a two-in-three chance of staying with 2degC of warming (albeit just a sliver when looking at the Paris baseline of surface air temperature). If one sets aside the warnings of the IPCC report and accepts the upper limit of the Paris goals as written--keeping warming "well below" 2degC--one cannot reasonably interpret that bit of white space as a greenlight for new fossil fuel development. Rather, it offers a chance to manage the decline of fossil fuel extraction so that warming actually stays "well below"--rather than barely below--the 2-degree danger line.

Furthermore, given what the new report tells us about uncertainties in the budgets, a precautionary approach would imply aiming as low as possible. For example, the IPCC report authors caution, "Remaining budgets applicable to 2100, would approximately be 100 Gt CO2 lower...to account for permafrost thawing and potential methane release from wetlands in the future."

In short, while the larger budgets may give a welcome increase to our chance of success, there is still no room for new fossil fuel development.

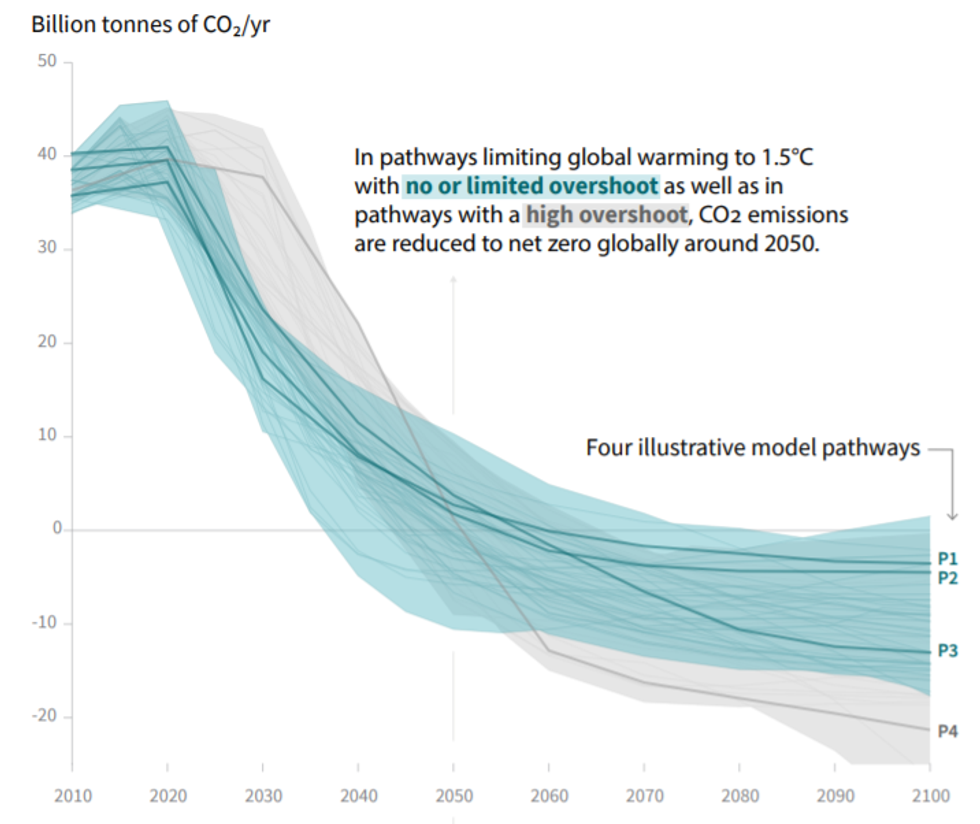

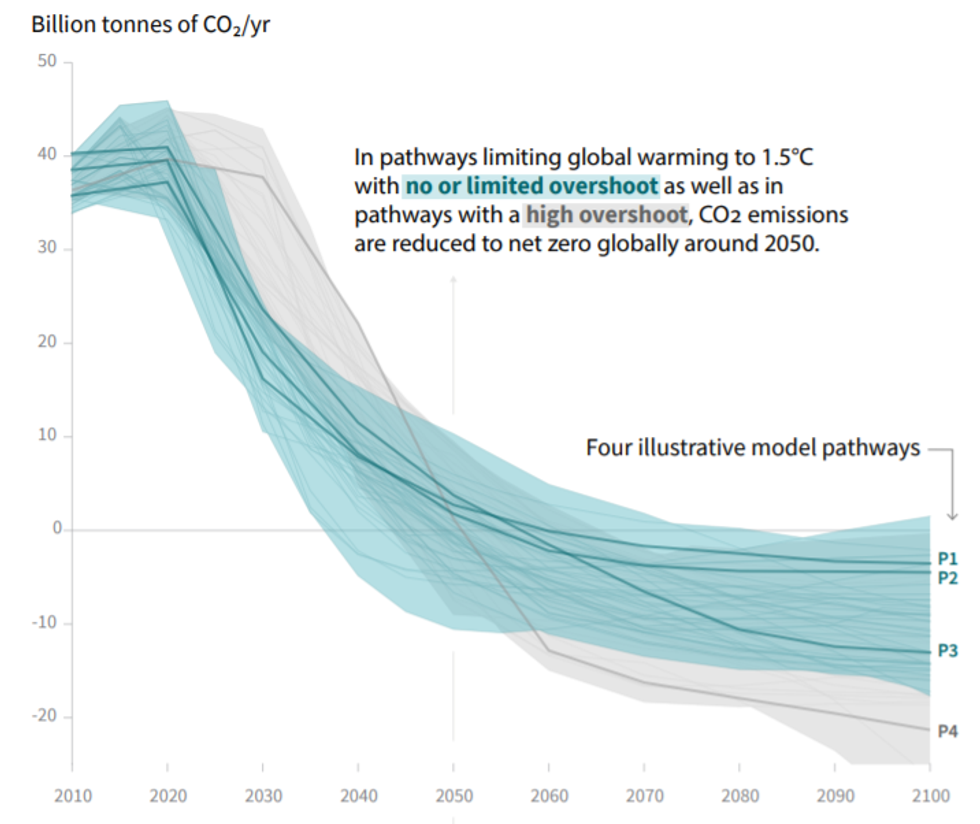

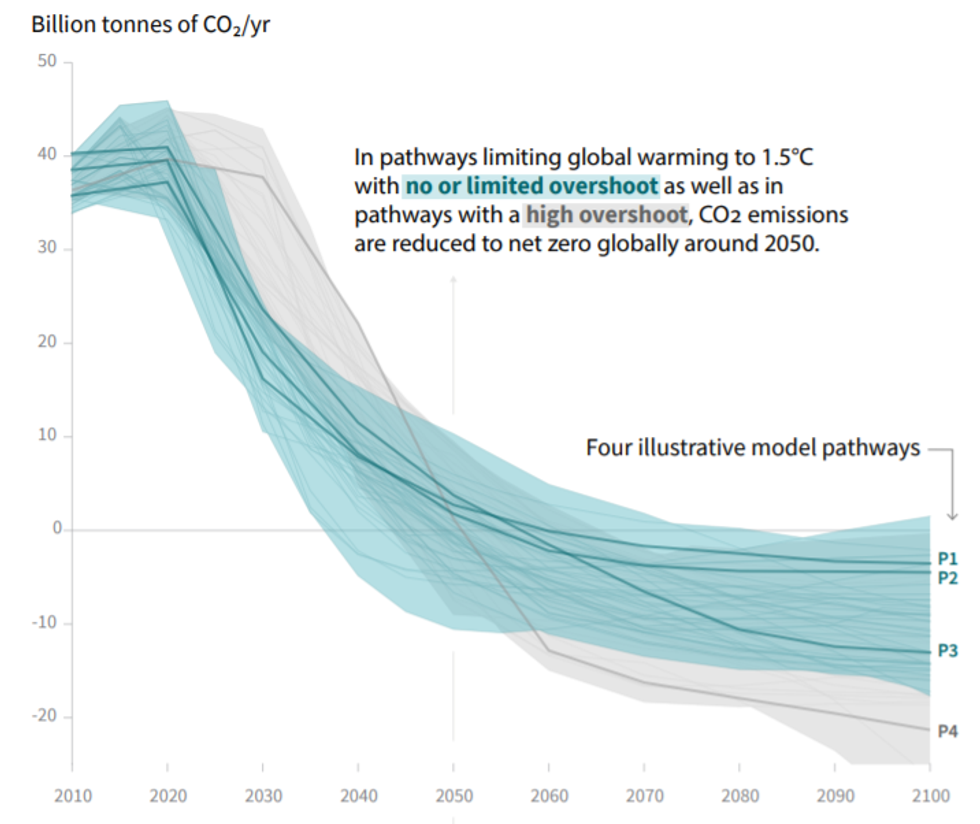

The IPCC report makes clear that, irrespective of whether there is slightly more or less space in carbon budgets, there is no time to lose in rapidly reducing emissions. The report indicates that keeping warming within 1.5degC will require reducing carbon pollution by about 45 percent from 2010 levels by 2030 and reaching net zero emissions around 2050, as illustrated in the figure below from the report's Summary for Policymakers. Steering the world onto such a pathway will require"rapid and far-reaching" transitions and "deep emissions reductions in all sectors."

Global Total Net CO2 Emissions in Model Pathways Limiting Global Warming to 1.5degC

The report goes on to explain that the longer the world's countries delay in serious emissions cuts, the more they will be required to rely on so-called carbon dioxide removal (CDR) technologies in subsequent decades. The report also provides a warning of the ecological and social risks--and potential infeasibility--of this approach. "CDR deployed at scale is unproven and reliance on such technology is a major risk in the ability to limit warming to 1.5degC," the report states. This topic deserves its own dedicated blog post. For now, I'll leave it at this: Large-scale reliance on carbon dioxide removal technologies is, unsurprisingly, exactly what many fossil fuel companies point to in their own "climate" scenarios--because it would extend the lifetime of their fossil fuel business model.

Near-zero emissions by 2050 would mean close to zero fossil fuel extraction by 2050. If governments find the political will to heed the science and commit to a managed transition off of fossil fuel extraction, there will be a way. We have the clean technologies we need.

On the other hand, continuing to build out the fossil fuel economy risks putting the 1.5degC climate limit out of reach in the very-near future, and that would put millions of additional lives at risk. Rather than inviting climate and/or economic chaos, it's time for political leaders to plan seriously for climate success--to end the fossil fuel era in an equitable way.

Notes:

[1] Carbon budgets are taken from Table 2.2 of the AR5 Synthesis Report, and adjusted to remaining space from the start of 2018 (subtracting approximately 40 Gt CO2 per year for 2012-2017)

[2] See p. 16, footnote 14 of the SR1.5 Summary for Policymakers.

[3] The SR1.5 Summary for Policymakers cites the GSAT-based budget for a 50 percent chance at 1.5degC to be 580 Gt CO2 (see C1.3 on p. 16). The budgets using GSAT are in the process of being added to Chapter 2 of the SR1.5, and Table 2.2 in particular, to be consistent with the final Summary for Policymakers. The pending edits cite 1170 Gt CO2 as the GSAT-based budget for a 66 percent chance of limiting warming to 2degC. The GMST-based budgets for varying temperature limits and probabilities are found in the SR1.5 in Chapter 2, Table 2.2.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

Since the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released its new, must-read report on the urgency of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, we at Oil Change International have been receiving some common questions: What are the implications for our analysis of what the Paris accord's goals mean for fossil fuel production? What about the IPCC's use of larger carbon budgets, compared to its last major report? What, if any, new conclusions do we draw?

The quick summary is this: It's clear that the IPCC's 1.5-degree report clarifies and adds urgency to our call for a managed decline of fossil fuel production. Winding down the largest source of carbon emissions--the oil, gas, and coal extracted by the fossil fuel industry--will be essential to achieving deep cuts in carbon emissions within the next decade, as the report warns is necessary. In this post, I'll unpack three key takeaways:

(Questions such as, Is there hope? (yes), and, Is this possible? (yes), are also critical parts of the discussion right now. I focus here the technical aspects related to our analysis.)

First, a bit of background: We at Oil Change International (OCI) first analyzed the limits that the Paris goals imply for fossil fuel production in 2016, and the results were sobering. In our report, The Sky's Limit: Why the Paris Goals Require a Managed Decline of Fossil Fuel Production, we found that the oil, gas, and coal in existing fields and mines globally contain enough potential carbon emissions to push the world beyond the Paris climate goals.

We arrived at this result by using carbon budgets from the IPCC's 5th Assessment Synthesis Report, which reflected the scientific consensus at the time. We took budgets that were consistent with the range of the Paris goals--aiming to limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (degC) or "well below" 2degC. We then compared those budgets to the potential cumulative carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from already-developed fossil fuel reserves globally. You can see the results in the figure below.

Developed Fossil Fuel Reserves, Compared to Carbon Budgets in the IPCC 5th Assessment Report [1]

We drew two primary conclusions from these results:

These recommendations were informed by our understanding of the dynamics of carbon lock-in. Developed reserves represent the oil, gas, and coal that the fossil fuel industry has already invested in extracting--the capital is sunk, the wells have been (or are being) drilled, the pits dug, and the related infrastructure constructed. Once a project is operating, there are economic, political, and legal factors that push for continued operation and present barriers to early closure.

Given the hard limit to how much fossil fuel can be extracted, and given the inertia behind existing projects, continuing to expand the footprint of the fossil fuel industry now risks two potentially overlapping outcomes: 1) Climate chaos, as the industry locks in levels of emissions that far exceed the Paris limits; and/or; 2) Economic chaos, from a sudden scramble to end fossil fuel production and use at a later date.

How has the new IPCC report adjusted our thinking?

The most important way the new IPCC has changed our thinking is that it has persuaded us that we need to aim to limit warming to 1.5 degrees, not just "well below 2 degrees." It's important to remember that 1.5degC exists as a goal within the Paris accord because some of the world's most climate-vulnerable nations demanded it, asserting this level of ambition as essential to their survival. The IPCC report provides powerful scientific backing for their call.

The report finds that exceeding 1.5degC of warming and hitting the 2degC threshold would put millions more people at risk of death, poverty, water and food shortages, and displacement from rising sea levels, while increasing the odds of irreversible, runaway ruptures in our climate system. We can significantly lessen the loss of human lives, whole communities, and ecosystems if governments interpret the upper limit of the Paris agreement--of keeping warming "well below" 2degC--to mean limiting it to 1.5degC.

Accordingly, we at OCI are shifting how we emphasize these goals in our own analysis, referring to 1.5degC first and as the primary aim when we discuss the Paris goals. We expect the IPCC report will encourage some governments and others to do the same.

One element of the new IPCC report has sparked questions and some confusion: the shifting size of the carbon budgets. As a basic concept, carbon budgets are relatively simple. They indicate how much CO2 can be emitted before the world reaches a certain temperature threshold. But calculating them depends on a variety of factors: how you measure the level of warming to date, how you measure temperatures (i.e., by air, sea, or a combination), how you define a "pre-industrial" baseline for human-caused emissions, exactly how many emissions have occurred since then, and how other greenhouse gas emissions influence the climate.

Since the IPCC's 5th Assessment Report, released in 2014, scientists have continued to examine the assumptions and methods that go into calculating carbon budgets. A much-debated paper released last year by Millar et al. (see our commentary on it here) proposed a new methodology, shifting the reference period from which models calculate carbon budgets to the recent past rather than pre-industrial times. Since the new reference period experienced slightly less warming than indicated by the models, the new methodology concluded that remaining carbon budgets for the 1.5degC and 2degC temperature thresholds may be larger as a result. The IPCC's 1.5-degree report adopted this new methodology, estimating that carbon budgets are roughly 300 gigatonnes (Gt) larger compared to those published in the 5th Assessment Report,[2] while noting that significant uncertainty remains around the size of this adjustment.

This is an active, ongoing scientific debate (for instructive overviews, read briefs from Climate Analytics and Carbon Brief). As such, it's not yet clear if the larger carbon budgets in the latest IPCC report fully reflect a new scientific consensus. In fact, it's so unsettled that the IPCC report gives two sets of budgets for each ambition level, based on different observational datasets. Some scientists have already said the report is too conservative, overstating remaining carbon budgets (in both versions) and understating risks. It's perhaps a case of unfortunate timing for the IPCC report, as it had to be written while that debate was just getting started.

Rather than waiting for a new consensus to be settled, let's take a look at what these larger budgets would mean if they're right. If we have a bit more space in global carbon budgets than previously thought, that's clearly a good thing. It would increase our chances of limiting catastrophic climate changes. Does this also imply there is some room to expand fossil fuel production?

The figure below shows how our original Sky's Limit calculation of developed fossil fuel reserves compares to the larger carbon budget sizes in the latest IPCC report (using the same 50 and 66 percent probability levels for 1.5degC and 2degC respectively). The bottom, darkest portions of the carbon budget bars show the budgets from the 5th Assessment Report (AR5), updated to reflect CO2 emissions through the end of 2017. The middle-shaded portions reflect the larger carbon budgets from the Special Report on 1.5 degrees (SR1.5) that use the same measure of warming as the 5th Assessment Report--global surface air temperature (GSAT). The top-shaded regions show the larger budgets based on a different temperature measure--global mean surface temperature (GMST), the average of air and sea surface temperatures.

For context, observational datasets generally use GMST, which is why the Millar et al. paper, based on observed warming to date, used them. On the other hand, the AR5, the scientific basis on which the Paris Agreement was reached, relied on GSAT. (For the sake of brevity, this is a simplification of the underlying science.) For assessing the Paris goals, one could argue against shifting goalposts. We look at both sets, since they both appear in the SR1.5.

Developed Fossil Fuel Reserves, Compared to Updated IPCC Carbon Budgets (GSAT and GMST) [3]

In each of these cases, developed reserves still significantly exceed the carbon budgets for a one-in-two chance of limiting warming to 1.5degC. Developed reserves are double the carbon budget for 1.5degC that's based on GSAT, after adding in optimistic estimates of future land use and cement manufacture emissions (which are more difficult to reduce than energy sector emissions).

With the larger budgets, there is some space between estimated emissions and the carbon budget limits for a two-in-three chance of staying with 2degC of warming (albeit just a sliver when looking at the Paris baseline of surface air temperature). If one sets aside the warnings of the IPCC report and accepts the upper limit of the Paris goals as written--keeping warming "well below" 2degC--one cannot reasonably interpret that bit of white space as a greenlight for new fossil fuel development. Rather, it offers a chance to manage the decline of fossil fuel extraction so that warming actually stays "well below"--rather than barely below--the 2-degree danger line.

Furthermore, given what the new report tells us about uncertainties in the budgets, a precautionary approach would imply aiming as low as possible. For example, the IPCC report authors caution, "Remaining budgets applicable to 2100, would approximately be 100 Gt CO2 lower...to account for permafrost thawing and potential methane release from wetlands in the future."

In short, while the larger budgets may give a welcome increase to our chance of success, there is still no room for new fossil fuel development.

The IPCC report makes clear that, irrespective of whether there is slightly more or less space in carbon budgets, there is no time to lose in rapidly reducing emissions. The report indicates that keeping warming within 1.5degC will require reducing carbon pollution by about 45 percent from 2010 levels by 2030 and reaching net zero emissions around 2050, as illustrated in the figure below from the report's Summary for Policymakers. Steering the world onto such a pathway will require"rapid and far-reaching" transitions and "deep emissions reductions in all sectors."

Global Total Net CO2 Emissions in Model Pathways Limiting Global Warming to 1.5degC

The report goes on to explain that the longer the world's countries delay in serious emissions cuts, the more they will be required to rely on so-called carbon dioxide removal (CDR) technologies in subsequent decades. The report also provides a warning of the ecological and social risks--and potential infeasibility--of this approach. "CDR deployed at scale is unproven and reliance on such technology is a major risk in the ability to limit warming to 1.5degC," the report states. This topic deserves its own dedicated blog post. For now, I'll leave it at this: Large-scale reliance on carbon dioxide removal technologies is, unsurprisingly, exactly what many fossil fuel companies point to in their own "climate" scenarios--because it would extend the lifetime of their fossil fuel business model.

Near-zero emissions by 2050 would mean close to zero fossil fuel extraction by 2050. If governments find the political will to heed the science and commit to a managed transition off of fossil fuel extraction, there will be a way. We have the clean technologies we need.

On the other hand, continuing to build out the fossil fuel economy risks putting the 1.5degC climate limit out of reach in the very-near future, and that would put millions of additional lives at risk. Rather than inviting climate and/or economic chaos, it's time for political leaders to plan seriously for climate success--to end the fossil fuel era in an equitable way.

Notes:

[1] Carbon budgets are taken from Table 2.2 of the AR5 Synthesis Report, and adjusted to remaining space from the start of 2018 (subtracting approximately 40 Gt CO2 per year for 2012-2017)

[2] See p. 16, footnote 14 of the SR1.5 Summary for Policymakers.

[3] The SR1.5 Summary for Policymakers cites the GSAT-based budget for a 50 percent chance at 1.5degC to be 580 Gt CO2 (see C1.3 on p. 16). The budgets using GSAT are in the process of being added to Chapter 2 of the SR1.5, and Table 2.2 in particular, to be consistent with the final Summary for Policymakers. The pending edits cite 1170 Gt CO2 as the GSAT-based budget for a 66 percent chance of limiting warming to 2degC. The GMST-based budgets for varying temperature limits and probabilities are found in the SR1.5 in Chapter 2, Table 2.2.

Since the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released its new, must-read report on the urgency of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, we at Oil Change International have been receiving some common questions: What are the implications for our analysis of what the Paris accord's goals mean for fossil fuel production? What about the IPCC's use of larger carbon budgets, compared to its last major report? What, if any, new conclusions do we draw?

The quick summary is this: It's clear that the IPCC's 1.5-degree report clarifies and adds urgency to our call for a managed decline of fossil fuel production. Winding down the largest source of carbon emissions--the oil, gas, and coal extracted by the fossil fuel industry--will be essential to achieving deep cuts in carbon emissions within the next decade, as the report warns is necessary. In this post, I'll unpack three key takeaways:

(Questions such as, Is there hope? (yes), and, Is this possible? (yes), are also critical parts of the discussion right now. I focus here the technical aspects related to our analysis.)

First, a bit of background: We at Oil Change International (OCI) first analyzed the limits that the Paris goals imply for fossil fuel production in 2016, and the results were sobering. In our report, The Sky's Limit: Why the Paris Goals Require a Managed Decline of Fossil Fuel Production, we found that the oil, gas, and coal in existing fields and mines globally contain enough potential carbon emissions to push the world beyond the Paris climate goals.

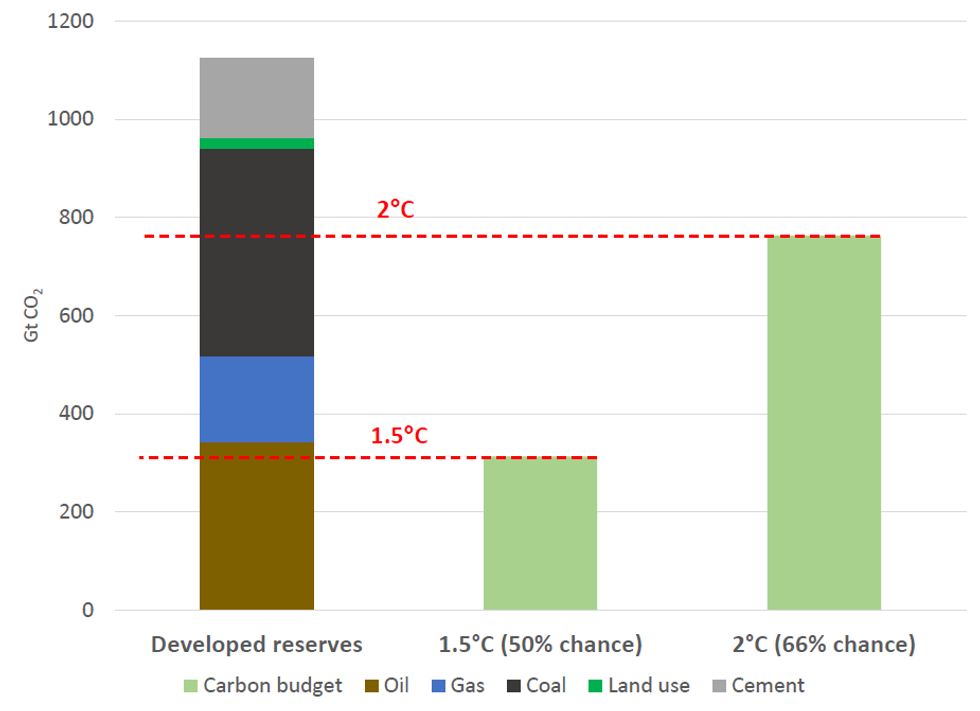

We arrived at this result by using carbon budgets from the IPCC's 5th Assessment Synthesis Report, which reflected the scientific consensus at the time. We took budgets that were consistent with the range of the Paris goals--aiming to limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (degC) or "well below" 2degC. We then compared those budgets to the potential cumulative carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from already-developed fossil fuel reserves globally. You can see the results in the figure below.

Developed Fossil Fuel Reserves, Compared to Carbon Budgets in the IPCC 5th Assessment Report [1]

We drew two primary conclusions from these results:

These recommendations were informed by our understanding of the dynamics of carbon lock-in. Developed reserves represent the oil, gas, and coal that the fossil fuel industry has already invested in extracting--the capital is sunk, the wells have been (or are being) drilled, the pits dug, and the related infrastructure constructed. Once a project is operating, there are economic, political, and legal factors that push for continued operation and present barriers to early closure.

Given the hard limit to how much fossil fuel can be extracted, and given the inertia behind existing projects, continuing to expand the footprint of the fossil fuel industry now risks two potentially overlapping outcomes: 1) Climate chaos, as the industry locks in levels of emissions that far exceed the Paris limits; and/or; 2) Economic chaos, from a sudden scramble to end fossil fuel production and use at a later date.

How has the new IPCC report adjusted our thinking?

The most important way the new IPCC has changed our thinking is that it has persuaded us that we need to aim to limit warming to 1.5 degrees, not just "well below 2 degrees." It's important to remember that 1.5degC exists as a goal within the Paris accord because some of the world's most climate-vulnerable nations demanded it, asserting this level of ambition as essential to their survival. The IPCC report provides powerful scientific backing for their call.

The report finds that exceeding 1.5degC of warming and hitting the 2degC threshold would put millions more people at risk of death, poverty, water and food shortages, and displacement from rising sea levels, while increasing the odds of irreversible, runaway ruptures in our climate system. We can significantly lessen the loss of human lives, whole communities, and ecosystems if governments interpret the upper limit of the Paris agreement--of keeping warming "well below" 2degC--to mean limiting it to 1.5degC.

Accordingly, we at OCI are shifting how we emphasize these goals in our own analysis, referring to 1.5degC first and as the primary aim when we discuss the Paris goals. We expect the IPCC report will encourage some governments and others to do the same.

One element of the new IPCC report has sparked questions and some confusion: the shifting size of the carbon budgets. As a basic concept, carbon budgets are relatively simple. They indicate how much CO2 can be emitted before the world reaches a certain temperature threshold. But calculating them depends on a variety of factors: how you measure the level of warming to date, how you measure temperatures (i.e., by air, sea, or a combination), how you define a "pre-industrial" baseline for human-caused emissions, exactly how many emissions have occurred since then, and how other greenhouse gas emissions influence the climate.

Since the IPCC's 5th Assessment Report, released in 2014, scientists have continued to examine the assumptions and methods that go into calculating carbon budgets. A much-debated paper released last year by Millar et al. (see our commentary on it here) proposed a new methodology, shifting the reference period from which models calculate carbon budgets to the recent past rather than pre-industrial times. Since the new reference period experienced slightly less warming than indicated by the models, the new methodology concluded that remaining carbon budgets for the 1.5degC and 2degC temperature thresholds may be larger as a result. The IPCC's 1.5-degree report adopted this new methodology, estimating that carbon budgets are roughly 300 gigatonnes (Gt) larger compared to those published in the 5th Assessment Report,[2] while noting that significant uncertainty remains around the size of this adjustment.

This is an active, ongoing scientific debate (for instructive overviews, read briefs from Climate Analytics and Carbon Brief). As such, it's not yet clear if the larger carbon budgets in the latest IPCC report fully reflect a new scientific consensus. In fact, it's so unsettled that the IPCC report gives two sets of budgets for each ambition level, based on different observational datasets. Some scientists have already said the report is too conservative, overstating remaining carbon budgets (in both versions) and understating risks. It's perhaps a case of unfortunate timing for the IPCC report, as it had to be written while that debate was just getting started.

Rather than waiting for a new consensus to be settled, let's take a look at what these larger budgets would mean if they're right. If we have a bit more space in global carbon budgets than previously thought, that's clearly a good thing. It would increase our chances of limiting catastrophic climate changes. Does this also imply there is some room to expand fossil fuel production?

The figure below shows how our original Sky's Limit calculation of developed fossil fuel reserves compares to the larger carbon budget sizes in the latest IPCC report (using the same 50 and 66 percent probability levels for 1.5degC and 2degC respectively). The bottom, darkest portions of the carbon budget bars show the budgets from the 5th Assessment Report (AR5), updated to reflect CO2 emissions through the end of 2017. The middle-shaded portions reflect the larger carbon budgets from the Special Report on 1.5 degrees (SR1.5) that use the same measure of warming as the 5th Assessment Report--global surface air temperature (GSAT). The top-shaded regions show the larger budgets based on a different temperature measure--global mean surface temperature (GMST), the average of air and sea surface temperatures.

For context, observational datasets generally use GMST, which is why the Millar et al. paper, based on observed warming to date, used them. On the other hand, the AR5, the scientific basis on which the Paris Agreement was reached, relied on GSAT. (For the sake of brevity, this is a simplification of the underlying science.) For assessing the Paris goals, one could argue against shifting goalposts. We look at both sets, since they both appear in the SR1.5.

Developed Fossil Fuel Reserves, Compared to Updated IPCC Carbon Budgets (GSAT and GMST) [3]

In each of these cases, developed reserves still significantly exceed the carbon budgets for a one-in-two chance of limiting warming to 1.5degC. Developed reserves are double the carbon budget for 1.5degC that's based on GSAT, after adding in optimistic estimates of future land use and cement manufacture emissions (which are more difficult to reduce than energy sector emissions).

With the larger budgets, there is some space between estimated emissions and the carbon budget limits for a two-in-three chance of staying with 2degC of warming (albeit just a sliver when looking at the Paris baseline of surface air temperature). If one sets aside the warnings of the IPCC report and accepts the upper limit of the Paris goals as written--keeping warming "well below" 2degC--one cannot reasonably interpret that bit of white space as a greenlight for new fossil fuel development. Rather, it offers a chance to manage the decline of fossil fuel extraction so that warming actually stays "well below"--rather than barely below--the 2-degree danger line.

Furthermore, given what the new report tells us about uncertainties in the budgets, a precautionary approach would imply aiming as low as possible. For example, the IPCC report authors caution, "Remaining budgets applicable to 2100, would approximately be 100 Gt CO2 lower...to account for permafrost thawing and potential methane release from wetlands in the future."

In short, while the larger budgets may give a welcome increase to our chance of success, there is still no room for new fossil fuel development.

The IPCC report makes clear that, irrespective of whether there is slightly more or less space in carbon budgets, there is no time to lose in rapidly reducing emissions. The report indicates that keeping warming within 1.5degC will require reducing carbon pollution by about 45 percent from 2010 levels by 2030 and reaching net zero emissions around 2050, as illustrated in the figure below from the report's Summary for Policymakers. Steering the world onto such a pathway will require"rapid and far-reaching" transitions and "deep emissions reductions in all sectors."

Global Total Net CO2 Emissions in Model Pathways Limiting Global Warming to 1.5degC

The report goes on to explain that the longer the world's countries delay in serious emissions cuts, the more they will be required to rely on so-called carbon dioxide removal (CDR) technologies in subsequent decades. The report also provides a warning of the ecological and social risks--and potential infeasibility--of this approach. "CDR deployed at scale is unproven and reliance on such technology is a major risk in the ability to limit warming to 1.5degC," the report states. This topic deserves its own dedicated blog post. For now, I'll leave it at this: Large-scale reliance on carbon dioxide removal technologies is, unsurprisingly, exactly what many fossil fuel companies point to in their own "climate" scenarios--because it would extend the lifetime of their fossil fuel business model.

Near-zero emissions by 2050 would mean close to zero fossil fuel extraction by 2050. If governments find the political will to heed the science and commit to a managed transition off of fossil fuel extraction, there will be a way. We have the clean technologies we need.

On the other hand, continuing to build out the fossil fuel economy risks putting the 1.5degC climate limit out of reach in the very-near future, and that would put millions of additional lives at risk. Rather than inviting climate and/or economic chaos, it's time for political leaders to plan seriously for climate success--to end the fossil fuel era in an equitable way.

Notes:

[1] Carbon budgets are taken from Table 2.2 of the AR5 Synthesis Report, and adjusted to remaining space from the start of 2018 (subtracting approximately 40 Gt CO2 per year for 2012-2017)

[2] See p. 16, footnote 14 of the SR1.5 Summary for Policymakers.

[3] The SR1.5 Summary for Policymakers cites the GSAT-based budget for a 50 percent chance at 1.5degC to be 580 Gt CO2 (see C1.3 on p. 16). The budgets using GSAT are in the process of being added to Chapter 2 of the SR1.5, and Table 2.2 in particular, to be consistent with the final Summary for Policymakers. The pending edits cite 1170 Gt CO2 as the GSAT-based budget for a 66 percent chance of limiting warming to 2degC. The GMST-based budgets for varying temperature limits and probabilities are found in the SR1.5 in Chapter 2, Table 2.2.