Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. would have been 90 on January 15, so it's time for a progress report.

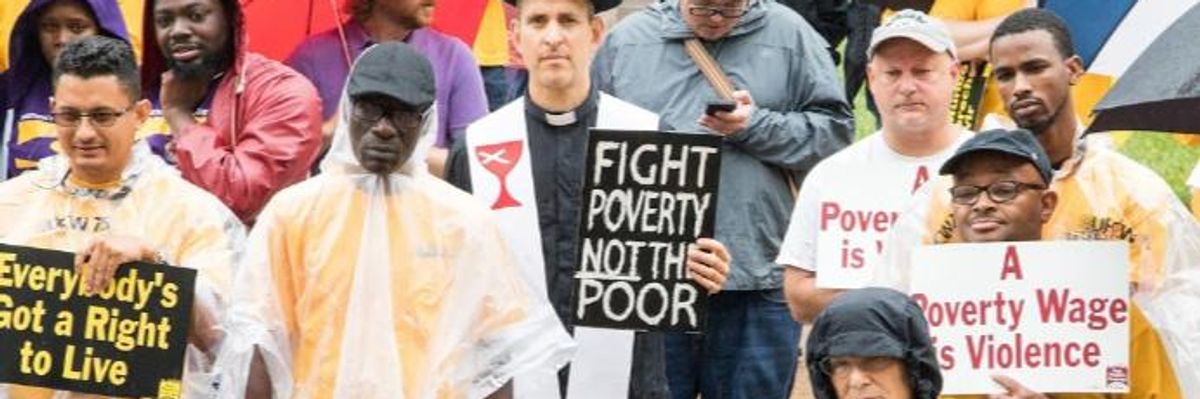

Fifty years after co-founding the Poor People's Campaign, a multiracial campaign for economic justice, the state of King's dream of racial equity and freedom from poverty is far from attained.

On the positive side, the U.S. Black unemployment rate reached historic lows in 2018. There's also been a modest recent uptick in median household wealth for Black, Latino, and white families alike. We could easily conclude that the racial economic divide is closing.

But we took a closer look in Dreams Deferred, a new report for the Institute for Policy Studies. And it revealed we have a long way to go.

While income statistics provide a valuable window into the annual fortunes of a family, an analysis of wealth tells us a more in-depth story about financial security and well-being.

Over the past three decades, a polarizing racial wealth divide has grown between White households and households of color.

Between 1983 and 2016, we found, median white household wealth grew from $105,300 to $140,500 -- a 33 percent increase after adjusting for inflation. On the other hand, the median Black family saw their wealth drop by more than half, to just $3,600.

Ninety years out from Dr. King's birth, in other words, the typical white family had 41 times more wealth than the typical Black family. (Latinos, out-owned by a factor of 22, fared only a little better.)

Even worse, if that trajectory continues, the gap will only get wider. White wealth is projected to grow, but the median Black family is on track to reach zero wealth over the next several decades.

Unsurprisingly, this also means that families of color are overrepresented on the poorest rungs of society. Some 21 percent of all U.S. households now have zero or negative wealth. That's concerning on its own, but that figure rises to 33 percent of Latino families and 37 percent of Black families.

As the U.S. becomes a majority black and brown society, it's a problem when such a huge percentage of the economy has stagnating wealth -- it amounts to the hollowing out of America's entire middle class, which hurts the whole economy.

Exclusion from asset-building undermines economic participation -- what economists call "aggregate demand" -- which results in diminished consumer spending, lower savings rates, and reduced homeownership and household formation.

Low levels of Black and Latino wealth, in fact, contributed to a 3 percent decline in overall U.S. household wealth over the decades we studied.

Four decades of stagnant wages have reinforced the historical patterns of racial division, while inequality in the broader society has undermined policies that might have helped close the gap.

Lawmakers who want to reverse these trends need to address the larger inequalities affecting all workers with initiatives to invest in good jobs, raise the minimum wage, and ensure the richest 1 percent pay their fair share of taxes. We need an economy rewired to work for everyone, not just the very wealthy.

But policymakers must also focus on efforts that help families who have historically been excluded from middle-class wealth building programs. This could include the creation of "baby bond" programs that seed asset-building accounts for all American newborns. Expansion of supports for first-time homebuyers and first-generation college students would also make a significant difference.

"There is nothing new about poverty," Dr. King said in his Nobel Peace Prize Address in 1964. "What is new, however, is that we have the resources to get rid of it."

Today those resources are concentrated in fewer hands than at almost any point in Dr. King's short life. To achieve the equal opportunity King lived and died for, we have to break these resources free so they can be invested in a nation that can make King's Dream a reality.